Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Holding a dustbin in front of his chest the young bare-chested student stands defiantly in the middle of a dusty road, facing down a squad of heavily-armed riot police.

Suddenly his body begins jerking crazily like a puppet on a string as bullets fired by a police marksman armed with a high-powered FN rifle smash through his useless shield and thud into his body. Almost four decades later this deadly tableau that played out on an Alexandra Township street a few days after the 16 June 1976 student uprising against the use of Afrikaans began in Soweto is still etched into my memory.

As a young reporter, I had been assigned that day to cover the unrest that had spread to Alex, as the flames of insurrection raced across apartheid South Africa like wildfire.

Over the weeks that followed, I regularly witnessed how police reacted with deadly brute force against student protesters armed only with rocks and anti-apartheid songs.

I also remember the mass meetings and marches in the early 70s against harsh apartheid laws by students at Johannesburg’s Wits University, which were inevitably broken up by police with vicious dogs and armed with whips, batons and tear gas.

So it was with a sense of déjà vu that I sat and watched on television almost two decades into South Africa’s young democracy as riot police used rubber bullets, stun grenades and tear gas to break up country-wide protests by students against above-inflation university fees hikes. They were also demanding that universities end the outsourcing of campus cleaning and maintenance jobs and for the people who do them to become full-time employees.

The fees protests came against a backdrop of a decrease in government subsidies leading to a growing dependency on student fees to make up shortfalls. But they also point to a much deeper problem at South African universities.

What South Africa has been witnessing is a reawakening of activism among students after a hiatus of almost two decades. For a week, campuses across the country embarked on the biggest nationwide student protests since the birth of the new democratic society in 1994.

But student and youth-led activism in South Africa is not new. It was pressure by the ANC Youth League leaders, including Nelson Mandela, which forced the organisation’s leadership to adopt a programme of action in 1949, including mass resistance tactics like strikes, boycotts and civil disobedience. It was also pressure on the leadership by youth that resulted in the 1952 launch of the Defiance Campaign against unjust apartheid laws.

But one big difference in these latest protests was the harnessing of social media as a rallying and activism tool. Powered by the #FeesMustFall hashtag the issue went viral with over half a million tweets and counting as Twitter became a powerful tool in the hands of the protestors.

With the ubiquity of smartphones among the students, Twitter became the go-to source to keep up with the rapidly unfolding story as the protests spread to 18 university campuses in eight of the country’s nine provinces, forcing the suspension of lectures and the cancelation of exams.

In the early days of the protests, some callers to radio shows at first dismissed the students’ actions as hooliganism.

But sentiments quickly turned in favour of the students as social media posts captured the unfolding drama in real time as the gloves came off and police moved against students who forced their way into the Parliamentary precinct in Cape Town.

Having evicted students, many holding their hands in the air as a sign of non-violence, the protest continued on the streets around Parliament–but once again police reacted with a heavy-handed response.

The growing anger and public support for the students were also fueled by the ANC-dominated Parliament carrying on with business as usual, even as the sound of stun grenades and rounds being fired rang through the chamber. Anger mounted as reports emerged that police were considering charging some of those arrested with high treason.

But Twitter also captured some poignant lump-in-the-throat moments as social media showed students of all races and political persuasions joining hands, and white students forming a human shield around black students in the belief that police were less likely to act against them.

The country-wide demonstrations culminated in a mass protest at the Union Buildings in Pretoria, the seat of South Africa’s government.

As demonstrators on the lawns outside chanted and sang, President Jacob Zuma met with university chancellors and students leaders, before his government capitulated to student demands. As the protests continued outside, Zuma appeared live on national TV and announced that there would be a 0% increase in university fees in 2016.

The news immediately spawned the jubilant new hashtag #FeesHaveFallen with some protesters saying that the suspension of 2016 fees was just the beginning of their struggle and vowed to continue the fight for free university education.

One thing is clear: after a week of protests by South Africa’s future generation of leaders, the country’s democracy was far stronger than when it began – and the high toll paid by the young man with the dustbin lid and others had not been in vain.

This column was posted on 27 October 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Many South African universities remain closed as thousands of students protest proposed fee hikes in what is believed to be some of the largest demonstrations to hit the country since apartheid. So far, 29 South Africans have been charged with violent offences as police continue to use heavy-handed tactics. High treason is among the alleged offences of protesters. And a court is seeking to ban the hashtag #feesmustfall, trending across South Africa.

The demonstrations began last week at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and have since spread around the country. South African president Jacob Zuma is meeting with students today to discuss tuition fees. Student negotiations have led to the government offering to cap fees hikes at 6% rather than proposed 10%, but demonstrations continue.

https://twitter.com/_MrBentleySA/status/657102323320229888

A protest outside parliament buildings in Cape Town on Wednesday led to clashes with South African riot police, who fired stun grenades at demonstrators. As the South African minister of higher education, Blade Nzimande, tried to reason with the crowd, he was met with calls for his resignation and placards reading: “Fees must fall, education for all”.

Students pushed past parliament gates and made their way inside the grounds. There, they sat on the ground, blocking entry and exit.

There were similar scenes on Monday night when students occupied the Bremner building at the Univerity of Cape Town. Police showed up in riot gear and arrested many for various offences.

The hashtag #FeesMustFall is being used on social media for people to voice their opinions and follow the protests. Following a request from the management at the University of Cape Town, the South African High Court has reportedly issued an interdiction against the hashtag in an attempt to silence dissent. Jane Duncan, professor of journalism at the University of Johannesburg is quoted in HTXT.Africa, saying that the inclusion of the hashtag demonstrates a clear misunderstanding of how the internet works, and in “its ill-defined breadth” could make criminals of anyone who uses it.

https://twitter.com/lesterkk/status/656909337101774849

How exactly the court intends to enforce a ban on a hashtag remains to be seen, but if true, it would have very serious implications for freedom of expression in South Africa.

A statement of solidarity with students in South Africa has been issued by the alumni of 24 schools, colleges and universities around the world, including King’s College London, as well as the universities of Cambridge, Oxford and Harvard. Signatories are “outraged by the use of violence from police”.

“Each of us stands in solidarity with the students, staff and workers protesting in South Africa, at parliament, universities and institutions of higher education. They are making history on streets and campuses across the country,” the statement reads.

“No unarmed and non-violent group of students should be dispersed with stun grenades, tear gassed, pepper sprayed, or shot at. All should be equal before the law, and we condemn the targeting of black students by the police. We call for the immediate release of students who have been arrested or detained in the context of peaceful protest action.”

Additional research by Anna Gregory, a student at The Crossley Heath School, Halifax, England.

Back in the days when the ruling National Party and their thought police ruled South Africa with an iron fist, one of the most powerful bodies tasked with enforcing Apartheid’s staunch Calvinistic values was the Film and Publications Board (FPB). A group of conservative, mainly Afrikaans men and women, it was their job to scrutinise and censor publications: books, movies and music.

Anything depicting even a hint of a mixing of races resulted in either an outright ban or, in the case of movies, ordered to make jarring cuts that often edited out key parts of the story. Suggestions of sex – between people of different colours – was verboten. Anything of a perceived political nature that didn’t fit in with ruling party’s narrow views was instantly banned.

The power to ban publications lay with the minister of the interior under the Publications and Entertainments Act of 1963. An entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica explains its purpose: “Under the act a publication could be banned if it was found to be ‘undesirable’ for any of many reasons, including obscenity, moral harmfulness, blasphemy, causing harm to relations between sections of the population, or being prejudicial to the safety, general.”

The result was that literally thousands of books, newspapers and other publications and movies were banned in South Africa – and possession of them was a criminal offence.

It led to some truly bizarre rulings, like the banning of Anna Sewell’s classic book Black Beauty because the censors, who clearly didn’t bother to read it, thought it was about a black woman.

I still have clear memories of returning from visits to multiracial Swaziland with banned publications hidden under carpets, slipped behind the dashboard or under spare wheels. That was how I got hold of a copy of murdered Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko’s I Write What Like and exiled South African editor Donald Woods’ Cry Freedom, about the life and death of Biko.

I still remember clearly how my heart skipped a beat when border guards checking through my car got uncomfortably close to uncovering my contraband literature. It was a huge risk because, had it been discovered, it would have meant prosecution and a criminal record for possession of banned literature.

Even having a copy of Playboy was a criminal offence and more than one South African found himself with a criminal record after a copy of the magazine was found stashed in his luggage on his return to South Africa from an overseas trip.

But when South Africa’s new, post-Apartheid constitution came into effect in 1996, it brought new freedoms for South Africans: books and movies banned by the Apartheid government were unbanned. Sex also came out into the open and, for those so inclined, pornography became freely available in the ubiquitous sex shops that opened their doors on high streets and side streets all over the country.

Then, the world wide web was in its infancy in South Africa, available only to the academics and privileged few who could afford it. But now, almost two decades later in a move that has raised fears of a new wave of censorship, the South African government last month approved a bill that has been widely criticised for seeking to curb internet freedoms. Informed by a draft policy drawn up by the FPB it seeks to amend the Film and Publications Act of 1996 – which had itself, replaced the Apartheid-era version of the Act – by adapting it for 21st century technological advances.

The amendments “provide for technological advances, especially online and social-media platforms, in order to protect children from being exposed to disturbing and harmful media content in all platforms (physical and online)”, according to a recent cabinet statement.

“The bill strengthens the duties imposed on mobile networks and internet service providers to protect the public and children during usage of their services,” it said, adding that the regulatory authority would not “issue licences or renewals without confirmation from the Film and Publication Board of full compliance with its legislation.”

The draft policy covers several areas including preventing children from viewing pornography online, hate speech and racist content.

But it also led to fear that it could be used to impose pre-publication censorship. These fears were allayed to some extent when a compromise was reached exempting content published by media registered with the Press Council of South Africa, which recently revised its press code to include regulation of online content exempted from the bill. But this is cold comfort for media who are not members, leaving them and bloggers, social media commentators and ordinary citizens vulnerable.

As it now stands anyone uploading content to the internet or posting content to social media would need to register with the FPB and submit their content before publishing anything. The proposed changes to the law would severely limit South Africa’s hard-earned, constitutional right to free speech, warn critics, who believe it would not pass constitutional muster.

This is reinforced by a legal opinion prepared for the Right to Know Campaign (R2K), which believes that the proposed bill is unconstitutional in several areas and also “unjustifiably limits the right to freedom of expression”. Opponents have made it clear that if it passes into law they will take it to the Constitutional Court.

There is no doubt that the battle lines have been drawn. Already 32,000 people opposing the bill have signed an Avaaz petition, while another 9,000 people have signed an R2K petition.

But the real issue is whether the FPB would be able to enforce it and whether trying to police the internet is just as bizarre as their predecessor’s banning of Black Beauty.

This column was posted on 10 Septemeber 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

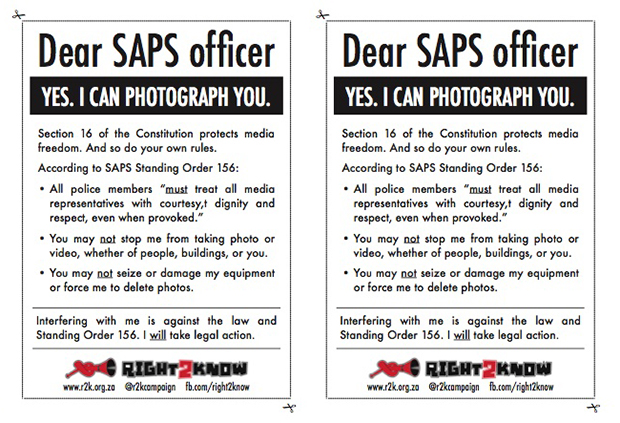

Despite Standing Order 156 incidents of police harassment of journalists continues. (Photo: Jaxons / Shutterstock.com)

Raymond Joseph has joined Index as a columnist

Working as a reporter in the spiraling cauldron of violence in South Africa of 70s and 80s, I learned early on to be wary of the police, who would often harass, bully and even detain journalists for doing their job.

Often it happened when police, armed to the teeth, went into operational mode, firing teargas, baton rounds and even live ammunition to brutally break up protests.

While reporters were also targeted, it was photographers and cameramen who were really in the firing line. Toting cameras, they were easily visible. Their pictures or footage were regularly destroyed by police and their equipment damaged or confiscated.

As a young reporter, I became adept at stashing exposed rolls of film, slipped to me by photographer colleagues, down the front of my trousers to hide them from the police.

Anyone who worked as a journalist in those turbulent times has stories to tell of being pushed around and bullied by the police who saw the media, especially those working for the anti-apartheid era English language Press, as “the enemy”.

Fast forward two decades into post-apartheid South Africa and practically every working journalist also has a story of police harassment to tell, often arising from incidents when they were reporting or filming police officers. Many less serious incidents go unreported, accepted by journalists as part of the job.

This is happening despite the South African Police Service’s own Standing Order 156 that sets out how the police must behave towards the media. The language used is unequivocal and leaves no room for misunderstanding. It makes it clear that police cannot stop journalists from taking photos or filming, including photographing police officers. It also states that “under no circumstances” may media be “verbally or physically abused” and “under no circumstances whatsoever, may a member willfully damage the camera, film, recording or other equipment of a media representative.”

Yet despite high-level meetings between media and the police’s top brass, who say that such actions are not condoned, incidents continue to occur. The most recent meeting was in June this year between the South African National Editors’ Forum (SANEF) and the Johannesburg Metro Police after a photographer and TV cameraman were roughed up when they filmed officers arresting a drunk driver.

Incidents are happening so regularly that the Right2Know Campaign has published a booklet and cards explaining their rights for journalists to give to police if they are interfered with while on the job.

But, problematically, Standing Order 156 only deals with media and makes no mention of civilians who film the police using mobile phones.

“One shortcoming that we discovered in putting this together is that there isn’t enough protection for bystanders with cell phones,” says R2K spokesman Murray Hunter. “Under the Constitution, everyone has the same right to freedom of expression – working journalists and ordinary people alike. It’s especially important since bystanders with cell phones are often sources for mainstream media.

“But the direct orders that we refer to in this advisory only instruct police not to interfere with old-school media workers. So bystanders may still find themselves in a situation where the Constitution recognises their right to freedom of expression, but a police officer on the ground doesn’t.”

An example of the important role now played by citizens in newsgathering is the video footage shot by a bystander on a mobile phone of police brutalising taxi driver Mido Macia for an alleged minor parking offence. Sent anonymously to the Daily Sun newspaper, it led to the dismissal of nine policemen, who are now on trial for the killing of Macia.

One beacon of hope is that Standing Order 156 is under review after SANEF complained to the police about repeated media harassment. R2K sees this as an opportunity to include protection of the rights of citizen reporters, as well as media professionals, says Hunter.

But that could take time and involve protracted negotiations. And even if it happens there is no guarantee that police will heed the force’s own rules, or that the harassment of journalists and others will end.

It seems that the more things change, the more they will stay the same.

This column was posted on 6 August 2015 at indexoncensorship.org