Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The government of Sudan cut the country off from the internet as protests against the end of fuel subsidies spread.

The release of the annual Freedom on the Net report for the first time includes a chapter on Sudan, authored by Index Award nominees GIRIFNA. This is more than timely, as the country is witnessing a new wave of widespread protests triggered by the Sudanese government’s announcement in late September 2013 that it will lift economic subsidies from fuel and other essential food items.

Based on a survey of 60 countries in Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2013, Sudan is categorised as “Not Free” with a score of 63, placing it among the bottom 14 countries in the category. As one of ten sub-Saharan African countries surveyed, Sudan joined Ethiopia as the two “Not Free” countries in the region. Kenya and South Africa were categorised as “Free” and the remaining six – Angola, Malawi, Nigeria, Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe – as “Partly Free”.

Sudan has invested heavily in its telecommunications infrastructure in the last decade, resulting in a steadily increasing internet penetration rate of 21 percent and a mobile penetration rate of 60 percent by the end of 2012, according to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). It also boasts the cheapest post-paid costs in the Middle East and North Africa in 2012, and healthy market competition amongst four telecommunications providers.

However, these infrastructural and economical advantages are highly reduced against the backdrop of a State that has little respect for freedom of expression, freedom of association, participation and peaceful assembly. The Sudanese regime is amongst the worst globally in terms its obstruction of the access to independent and diverse information both offline and online. A global study on press freedom conducted by Reporters without Borders earlier this year ranks Sudan at 170 out of 179 countries surveyed. This clearly reflects that the violations of freedom of expression impacting the traditional print media are also starting to reflect online.

The Sudan Revolts, the wave of protests triggered by economic austerity plans that hit the country between June and July 2012, was the first time the authorities implemented a large-scale crackdown and detentions of citizens using digital platforms to communicate, connect, coordinate and mobilise. Additionally, the government increased its deployment of a Cyber Jihadist Unit to monitor and hack into Facebook and email accounts of activists. The National Telecommunications Corporation (a government agency) also engages in the censoring and blocking of opposition online news forums and outlets. YouTube, for example, was blocked for two months in late 2012 in response to the “Innocence of Muslims” video.

The attacks on cyber dissidents during Sudan Revolts included the detention of digital activists, such as Usamah Mohammed, for up to two months, the forced exile of Sudan’s most prominent video blogger Nagla’a Sid Ahmad, and the kidnapping and torture of the Darfurian online journalist Somia Hundosa. Moreover, one of the most high profile political detainees from the Nuba Mountains, Jalila Khamis, spent nine months in detention without charges. When she was finally brought to trial in December 2012, the main evidence against her was a YouTube video taken by Sid Ahmad, in which Khamis testified about the shelling of civilians in the Nuba Mountains by the government.

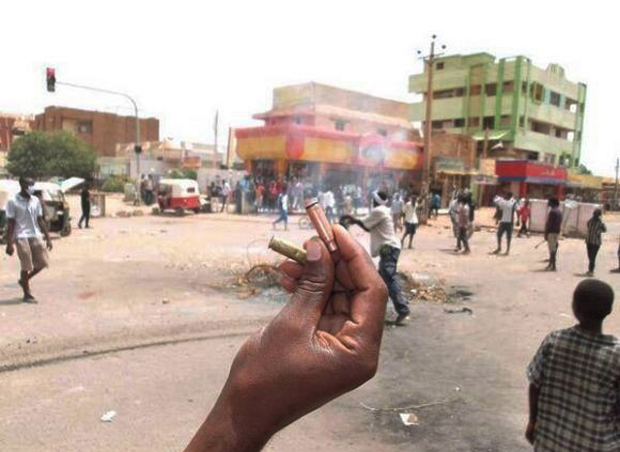

Since September 23 this year, authorities have responded to the new wave of protests with unprecedented violence toward peacefully protesting urban dwellers. More than 200 have been killed in Khartoum and Wad Madani by live bullets fired by riot police, national security agents, and/or state sponsored militias. According to a government statement, 600 citizens have been detained, though activists say that number is much higher. On Wednesday, September 25, the government shut down internet access for 24 hours. When the internet returned, it was much slower, with Facebook inaccessible on mobile phones and YouTube blocked or non-functional due to a very slow broadband connection.

The US sanctions imposed on Omer El Bashir’s regime since 1997 also continue to hinder the free access to the internet and the free flow of information as it limits access to a number of new media tools. This includes limited access to anti virus suites, e-document readers, and rich content multimedia applications that most Sudanese citizens cannot download. The inability to download software security updates makes many users in Sudan vulnerable to malware. Smart phone applications cannot be downloaded or purchased from the iTunes and/or Android stores.

Additionally, Sudan has a combination of restrictive laws that work together to impede freedom of expression both off and online, including the 2009 Printed Press Materials Law, and a new Media law that has recently appeared in Parliament, which officials have hinted would for the first include language restricting online content. Additionally, the National Security Act (2010) gives National Intelligence and Security Services the permission to arrest journalists and censor newspapers under the pretext of “national security,”. An IT Crime Law, in effect since 2007 criminalises websites that criticise the government or publishes defamatory materials. All these laws contradict Sudan’s National Interim Constitution, which guarantees the right to freedom of expression, association and assembly.

The two most influential independent newspapers in Sudan, Al-Sahafa and Al-Kartoum, have recently been bought by the National Intelligence

Security Service (NISS).

The NISS now owns 90% of all the independent newspapers in the country, according to Alnoor Ahmed Alnoor, the ex-editor in chief of Al-Sahafa.

The NISS purchased 65% of Al-Sahafa’s stock from a company called Bayader and a further 25% from Sideeq Wadaa, a businessman and member of the ruling NCP Party (with the remainder retained by the paper’s founder, Taha Ali Albashir). This follows the purchase of 80% of the stock of Al-Khartoum from its owner, Albagir Abdellah, five months ago.

Ownership represents the final stage in the Sudanese government’s campaign to silence independent voices in the media. Newspapers that refused to tow the NCP line or implement its agendas faced harassment, and fifteen newspapers were forcibly closed following the independence of South Sudan in 2011. Punitive taxes were also imposed, as was the case with the Al-Sudani between 2006 to 2011, which eventually forced the paper’s owner to sell it to a member of the NCP.

Khalid Abdelaziz, a one-time editorial manager of Al-Sudani says: “They used to demand about US$400,000 a year in their campaign against us while leaving their own newspapers paying little tax. They also used regulations to prevent us from the advertising. They gave us a choice, to implement their agendas or to sell our newspaper. We took the second choice”.

The new ownership has been followed by the resignation of key journalist. Interference led to Mozdalfa Osman to step down as editorial manager at Al-Khartoum: “I resigned because of the negative influence on my job and the implementing of NISS’s agenda, which contradicted my professionalism”.

Those that remain face increasing harassment, such as Al-Khartoum’s Mohamed Salih, winner of this year’s Peter Mackler prize, who faces pressure from his new editor-in-chief: “He calls me four times weekly asking to change some of the ideas in my column. I have never worked under such conditions before”.

Independent reporting in Sudanese has had a checkered history. The free press thrived for 57 years from 1903 to 1960 when first dictatorship came to the power. After the revolution of October 1964 independent newspapers once more operated until the second dictatorship in 1969, which nationalized all newspapers considered to have had a socialist orientation. With the second period of democracy, following the revolution of March 1985, another tranche of independent newspapers came into existence. However this once more came to an end when the current regime came to power in a military coup in June 1989.

Before the peace agreement with Sudan people liberation movement (SPLM) in 2005, NCP created shell companies to buy stakes in the newspapers, such as Alrai Alaam one of the oldest newspapers in Sudan. It has been published since 1948. The shell companies began buying stakes in 2002. The same process has been used with Alsahafa and Alkhartoum.

Hayder Almukashfi, who is responsible for the opinion pages on Al-Sahafa, said the newspaper has been greatly influenced by the new owners: “All the pages have been affected by the new polices and the opinion pages have been affected the most. The new owners sacked the previous editor in chief, who had been in the job for years, and have brought another one is a member of ruling NCP. This is an awful situation for freedom of speech in Sudan. The government can now claim there’s no censorship of the press because now the government is the press”.

This article was originally posted on 30 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

Reports of at least 50 dead have been received from Sudan.

There’s no trying to hide what’s happening within the urban centres of Sudan today. On Wednesday, September 25 at about 1pm, the Sudanese authorities completely shut down the country’s global internet for 24 hours. This happened against the backdrop of spreading peaceful protests following the regime’s decision to lift state subsidies from basic food items and fuel.

In the last few weeks, Sudan’s citizens have been feeling the burden of increasing prices as the Sudanese pound depreciated sharply, and purchasing power declined in a country where 46 percent of the population live in poverty. The lifting of subsidies was met with a popular outburst, especially after a public TV speech by President Omer Al Bashir made it clear that his government has no concrete solutions. He went on to mock the population saying they did not know what hot dogs were before he came to power.

The protests, which started in Wad Madani in Gaziera state, have so far spread to Sudan’s major towns including Nyala in war-struck Darfur. They have been met with unprecedented government violence in the Northern cities of Sudan which have traditionally been peaceful. Live ammunition has been used against protesters, many of whom are school students and youth in their early to mid twenties. By the third day of protests the death toll in Khartoum alone exceeded 100, and 12 in Wad Madani. There have been arrests amongst political leaders, activists and protesters, with more than 80 detainees from Madani alone.

Sudan’s government has cracked down violently, using live ammunition to disperse demonstrators.

Protesters are mainly calling for the regime to step down, with chants of, “liberty, justice, freedom”, “the people want the downfall of the regime”, and “we have come out for the people who stole our sweat”. These protests lack any political or civil society leadership, and so far not a single statement has come from the umbrella of opposition parties, the National Coalition Forces.

Crackdown on the internet and print media

The internet blackout imposed by Sudan’s National Congress Party (NCP) was an intentional ploy aimed at limiting the outflow of information, especially the very graphic images of protesters lying dead in the streets, as well as the images from hospital morgues showing protesters with fatal injuries to the head and upper torso areas. It is clear that this show of force is meant to frighten Sudanese citizens and deter additional protests. (Graphic Images: Street | Street)

This is not the first time the regime in Khartoum has shut down the internet. In June 2013 there was an 8-hour internet blackout during a gathering organized by the Ansar (an off-shoot of the Umma Party) that attracted thousands of people. During the protests last year, dubbed Sudan Revolts, the internet slowed down drastically on the night of June 29, before a large protest was announced.

Since the independence of South Sudan in July 2011, Sudan has also experienced a general clampdown on the media. On September 19, before the start of the protests on Monday, newspapers writing about the economic situation including Alayaam, Al Jareeda and the pro-government Al Intibaha, were confiscated. On Thursday, newspapers including included Al Ayaam and Al Jareeda, refused to print because of the government imposed censorship that prohibits any mention of the ongoing protests. Today Al Sudani and Al Mahjar newspapers (both pro-government) were confiscated, and Al Watan was not allowed to go to press.

The government of Sudan cut the country off from the internet as protests against the end of fuel subsidies spread.

With most citizens and activists relying completely on social media outlets and internet access through mobile phones to share information, footage and photos, the internet remains the only affordable means to communicate with the outside world. Other options, such as dial-up using modems are not viable for Sudan, as most people have no landlines to connect via modems and depend on mobile devices to access the internet.

During the internet blackout many reported that even SMS messages were blocked. And services such as tweeting via SMS were interrupted by the sole telecommunications provider that carries this service-Zain.

Popular anger and continuing protests

Contrary to the government’s intention the excessive use of force against protesters, the rising death toll and continuing rumours that the internet may be shut down again have not dissuaded citizens, but rather made them more angry and determined, with protests lasting long after midnight in Khartoum. As the streets of the capital and other towns filled up with security agents, riot police and armed government militias, citizens have nonetheless buried their dead in large and angry processions.

Today has been called Martyr’s Friday, in remembrance of all those who have fallen. Protests have been announced in all of Sudan’s towns. In some areas of Khartoum, citizens reported that they were not allowed into mosques for Friday prayers, and that the mosques had a heavy presence of security agents in civilian clothes. This move shows that the regime is anxious protests may follow after the prayers, as well as fearing the possible politicisation of the Friday sermons which may incite more anger.

Nonetheless, this has not deterred more than 2,000 protesters to congregate in Rabta Square, Shambat Barhry (in Khartoum). While writing this, a protester called me to say his internet was not working, and described that even leaders from the communist party, Popular Congress Party and others were starting to arrive. I could hear him with difficulty, but chants in the background were clear, “ya Khartoum, thouri, thouri”—Khartoum, revolt, revolt.

So far one thing is clear: these protests are not a replay of last year’s summer protests that were mainly triggered by university students and youth movements. These are street-supported protests–something that previous protests lacked and a game changer for the NCP who is gradually losing its grip on power.

This article was originally posted on 27 Sept 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

This article was edited on 5 November 2013 at 13:50. The article originally stated that the internet blackout took place on Wednesday 26 September. It took place on 25 September.

Sudan’s Public Order Law (POL) is making headlines after female activist and engineer Amira Osman was arrested on August 27 in Jebel Awliya, a suburb of Khartoum, for refusing to pull up her head-scarf. Amira is now facing trial for “indecent conduct” under Article 152 of the Sudanese penal code, and risks being punished with flogging and/or bail. Her next trial is scheduled for September 19.

In a calculated act of defiance against one of Africa’s most oppressive regimes, Ms. Osman recorded a video where she described the demeaning manner in which she was treated by Public Order Police (POP) and invited Sudanese citizens (men and women) to attend her trial, saying: “if you think that the Public Order Law is against you, come to Jabel Awliya’s Court…and let’s put the Public Order Law on trial”.

The first session of her trial was on September 1. It was attended by almost 100 regular citizens, civil society members and women’s rights activists. The trial was postponed when the judge did not show up due to sickness.

Osman’s trial is reminiscent of the POL case of Sudanese journalist Lubna Hussien, who captivated national and international attention in July 2009 when she and 12 other women were arrested in a restaurant in Khartoum for wearing trousers.

Public order laws or social control laws?

Sudan’s POLs date back to 1983. They were referred to back then as the September Laws, imposed by the authoritarian regime of President Jafaar Numeiri. He introduced Sharia corporal punishments (hudood) for acts such as consuming alcohol, stealing, gambling or mixing between the sexes. These laws fueled the national discontent that led to the uprising that toppled Numeiri in April 1985.

When the current regime took power in 1989 following a military coup, it introduced an extensive array of Public Order Laws. With the intention of creating an Islamic State, the National Islamic Front (as it was called back then) initiated a detailed “Civilization Project” that reached into every aspect of Sudanese social life, and placed restrictions on long entrenched traditional norms such as private parties with music, mixing between the sexes and the making and consumption of alcohol.

However, no other aspect of the Public Order Regime has altered the daily lives of Sudanese women like Article 152 of the Criminal Act of 1991 that says: “(1) Whoever commits, in a public place, an act, or conducts himself in an indecent manner, or a manner contrary to public morality, or wears an indecent, or immoral dress, which causes annoyance to public feelings, shall be punished, with whipping, not exceeding forty lashes, or with fine, or with both; (2) The act shall be deemed contrary to public morality, if it is so considered in the religion of the doer, or the custom of the country where the act occurs.”

Human rights lawyers have consistently pointed out that Article 152 is vague and does not define what is meant precisely by indecent clothing or indecent behaviour. It thus leaves a lot to be interpreted by POP and the judges in the Public Order Courts.

Prominent human rights lawyer Nabeel Adeeb recently commented in an op-ed that,”what is seen by me as indecent attire may be seen by someone else as decent”. He adds that from a religious perspective it’s hard to impose one uniform on women because it depends on their personal understanding of their faith. “Judges should not be god’s representatives on earth.” he says. Society’s understanding of “decent” attire is a constantly shifting concept, and Sudan’s diversity makes this even more complex and a matter that should not be decided in the courts. “It is an issue left to families and religious leaders, because it is linked to education and upbringing and not the law,” he concludes.

Poor and fleeing women targeted

No national statistics are available to shed light on how many women or men around Sudan are impacted by the Public Order Regime, however in 2008 the head of the Public Order Police in Khartoum said that in that year 41,000 persons were stopped under Article 152 and signed promissory documents “not to wear indecent clothing”.

Most POL cases are processed quickly in Public Order Courts without the presence of lawyers, with no due process and with judges who lack proper legal training.

Women’s rights activists who have been fighting this law for years point out that the stigma associated with being arrested by POP drive many women, who are less knowledgeable about their rights and more concerned about their reputation, into accepting summary trials in Public Order Courts where they are often flogged and/or have to pay a bail .

The women most impacted by the POL are not the urban educated women like Amira and Lubna, but rather the thousands of women fleeing conflicts and hard conditions in other regions such as the Nuba Mountains and Darfur, and who have to support their families by working in Khartoum’s informal sector selling tea, food or making a local millet-based beer called marisa.

Monim Adam, a human rights lawyer, says: “in most cases these women cannot afford the bail that can go up to $200, and they end up serving prison terms of up to one month. Many of them also endure sexual harassment that goes as far as rape, from the Public Order Police officers who have limited oversight”.

A prominent case that’s also running in the courts right now is that of Nuba Mountains woman Awadiya Ajabna. She was shot dead in March 2012 when she interfered as the POP were harassing her brother outside their family home, accusing him of being drunk. Ajabna died hours after POP fired shots that also injured her mother and sister.

This is not the first documented case of death at the hands of POP, as in 2010 a tea lady, Nadia Saboon was fleeing what is referred to as a Kashaa (a raid or sweep) by the POP. Saboon fell on a piece of metal and died due to the injury sustained. Raids and confiscations of the equipment of tea ladies by POP are a common practice in Khartoum, and it is done under the premise of “preserving the appearance of the public domain”.

Sudan has undergone severe limitations on fundamental rights after the separation of South Sudan in July 2011. In the last two years the Islamist regime of Omer Al Bashir has clamped down on freedom of the press, freedom of association and assembly, by closing newspapers and pro-democracy civil society organizations, and violently clamping down on peaceful protest.