9 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

The next morning, taking a taxi to the Cau Giay district on the west side of town, I pass several of the lakes that dot downtown Hanoi to arrive at a tree-line boulevard where Nha Nam, my publisher, fills an old building with louvered windows that open onto iron-fronted balconies. Already by ten in the morning a gray blanket of heat and humidity has draped itself over the city. Nha Nam’s ground-floor bookshop is filled with translations of Proust, Kundera, and Nabokov, and I am pleased to find a stack of my own books displayed next to Lolita. I introduce myself to the receptionist and am led upstairs to meet Nguyen Nhat Anh, chairman of the company, and Vu Hoang Giang, his vice-director and partner. I had actually met Giang the night before. Without my knowing that he would be there, he had attended a lecture I gave at the Hanoi Cinematheque and introduced himself afterwards. As the chairman of Nha Nam presents me with a bouquet of purple lotus blossoms, I fear that my remarks the previous evening may have been too candid.

Nguyen Nhat Anh, a slender man in a black tee shirt, jeans, and sandals, looks more like a coffee shop habitué than the editor of a major publishing company. Known for his literary nose, he works at a desk covered with books and manuscripts piled ten deep. His partner, Giang, wearing an open-necked polo shirt, is a tall, handsome fellow with a ready smile and a small tattoo decorating his right wrist. I imagine they have divided the corporate turf between them, with Anh responsible for scholarship and Giang for sales. Later I learn that a lot of the manuscripts piled on Anh’s desk are actually publishing contracts, while Giang has his own literary interests, and, in fact, he was the person who finally arranged to got my book published.

Thu Yen, the editor with whom I have been sparring for the last few years, has not been invited to this meeting. She remains at her desk in the contracts department, while another translator has been hired for the occasion—a young Vietnamese woman, a former office manager at an American law firm. As the scholarly Anh and smiling Giang discuss the nuances of Vietnamese publishing, the young woman’s translations get shorter and shorter, until finally she seems on the verge of giving up completely. Fortunately, I have brought my own translator, and we will spend several hours later that afternoon reconstructing the conversation.

I take a seat on the couch in Anh’s office. Outside the louvered windows, the cicadas in the trees are making a fearsome racket. Giang has already warned me an in email about the “tight and rather heavy-handed censorship system of state-owned publishers in Vietnam. This you may not fully imagine.” I am offered a cup of green tea and then we launch into a discussion of censorship, how it is handled generally in Vietnam and particularly in my case.

Anh takes the lead, giving lengthy, formal answers to my questions, until Giang takes over when the boss heads to the espresso machine next to his desk and brews himself a cup of coffee. I am tempted to ask for one myself but decide to be polite and stick with tea. Anh describes how the censors dictate even the smallest details. He gives as an example the fact that political figures must have honorifics. One is not allowed to refer to the founder of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as Ho Chi Minh. He has to be Bac Ho—Uncle Ho—which inscribes him simultaneously into Vietnamese family structure and history.

“Censorship is a very tough question,” says Anh. “We don’t really have a system or set of rules for how it’s handled. All we know is that lots of publishers didn’t dare to publish your book.”

The jalousie doors and windows in Anh’s office open onto a porch overlooking the street, but they remain closed against the heat. Other than his desk, groaning under its layer of books, and a coffee table, piled with yet more books, the room holds nothing more than the couch on which I am sitting and bare green walls.

“Because another book had been published on the same subject, we thought this improved our chances,” he says. “We were sure we could get your book in print.”

I ask Anh why he chose a northerner to translate my book, someone who missed the nuances and even the jokes told by its southern hero.

“The differences are like music,” he says. “Singers sing the same songs but give them different interpretations. When we translated Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, we tried to keep it honest to the southern dialect. But in your case, we thought we were dealing with a political book, a work of non-fiction. The people who read these books are northerners, and you have to make the text understandable for them.”

I ask Anh and Giang to talk in more detail about censoring my book. They describe the by now well-known process, which begins with the translation, commissioned from someone who knows how the game is played. Then the book goes to the editor, who removes all the “sensitive” material.

“How does he know what to remove?”

Nha Nam Vice Director Vu Hoang Giang and Chairman Nguyen Nhat Anh (Photo: Thomas Bass)

“The process is dangerous, dangerous to the author, but also dangerous to the publisher,” says Anh. By this point in the conversation, he has kicked off his sandals and is cooling his bare feet on the tile floor. Overhead, a fan swirls tepid air around the room. Temperatures in Hanoi this spring are spiking over a hundred.

Anh tells me the story of a book of poems the company published in 2006 by an author named Tran Dan. Dan’s work has been banned in Vietnam since the 1950s, when he was involved in the nhan van giai pham affair. This was Vietnam’s version of Mao’s cultural revolution, a purging of writers, artists, and musicians who were blacklisted, imprisoned, and banned for fifty years. One of these artists was Van Cao, who, in 1945, had composed Vietnam’s national anthem. From 1957 until 1986, Vietnamese found themselves in the peculiar position of being allowed to play but not sing Van Cao’s anthem. Only when the words were changed was the song once again performed. Van Cao himself had long ago stopped composing, thereby joining the ranks of Vietnamese artists—hundreds of them, from the 1950s to the present—who have been driven into silence or exile.

With Mao long dead and his cultural revolution discredited, Nha Nam thought it was safe to bring the poet Tran Dan back into print. They had obtained a publishing license from a state-owned company in Danang and printed some of his poems when all hell broke loose. “The police came to the book fair and seized all our books,” says Anh. “Then they raided our offices and destroyed more books. This was terrifying for us. We thought we were going to be closed down and put out of business.”

“What went wrong?” I ask.

Anh lowers his voice and mentions the name of an agency named A25.

“Now it’s A87,” Giang says, correcting him.

Governmental departments that begin with the letter “A,” which stands for “an ninh,” meaning “security,” are legion, and A25—now known as A87—is the one that deals with publishers.

“In any case, it’s Cultural Security, cuc an ninh van hoa,” says Anh.

“What’s their address?” I ask.

“They don’t have an address,” he says, implying they are everywhere. The two men discuss among themselves in terse sentences what went wrong. None of their interchange is translated.

“There is no single organization in charge of censorship,” says Anh. “There are a lot of people involved.” Again, he mentions the Ministry of Public Security.

Giang mentions the Ministry of Information and Communication. “This is the office in charge of publishing,” he says.

Anh adds to this list the national police and other organizations. “It’s like a cloud,” he says. “They are everywhere.”

“Usually they don’t arrest editors,” he says. “This can happen to writers, but editors generally know in advance when they’re going to run into trouble.”

I ask them to speak in more detail about the censorship involved in publishing my book. This is when I hear for the first time about Nguyen The Vinh. Vinh is the man who produced the final list of cuts to my book and secured its publishing license. From their description of him, I get the idea that Vinh is a heavy-weight in the publishing world. The former director of various companies, he now works as an editor at Hong Duc, the state-owned publisher attached to the Ministry of Information and Communication. This company not only gave my book its publishing license, it also put its logo on the title page. Actually, the book has two logos on the title page: Nha Nam’s trudging water buffalo, with a book-reading buffalo boy (or girl) on its back, and Hong Duc’s white H inscribed inside a black D.

I learn another interesting fact about Vinh. He was the editor who secured the publishing license for Professor Berman’s Perfect Spy. The Vietnamese translation of this book was supposed to grease the skids for mine, and who better to perform this feat than the man who had already done it before.

As Anh busies himself making his cup of espresso, Giang takes over the narrative. “Your book was rejected by five or six publishers,” he says. “Other publishers who looked at it wanted to interfere a lot, changing the content. They kept asking to cut more and more. We resisted these changes, until finally Nguyen The Vinh agreed to publish it.”

“And what changes did he demand?” I ask.

Anh is pacing behind his desk. A frown darkens Giang’s face. “When you talk to him, you shouldn’t be too hard in your questions,” he says. “It could affect Vinh and the chances for your book to remain on sale.”

“Who asked Vinh to get involved?” I ask.

“Giang approached him,” says Anh. I can see that these men are nervous about talking to me in such detail. By now, both of them are sitting with their arms crossed over their chests.

“The publishers at Hong Duc wanted to write a forward to your book,” says Anh. “We rejected this idea.”

I can imagine how Hong Duc’s introduction would have reworked the standard tropes about Pham Xuan An as a “perfect” spy, an impeccable Communist cadre, who, nonetheless, garnered fulsome praise from his Western admirers. I am grateful to my editors for saving me this embarrassment.

“It was Vinh who took personal responsibility for publishing your book,” says Anh.

“You mean it can still be censored?”

Your book could be seized tomorrow,” he says. “No one knows where the trouble could come from. We have yet to see any negative signs, but someone can always find ‘sensitive’ items in a book.”

“What subjects would you like me to avoid talking about while I am in Vietnam?” I ask.

“Please remember that Vinh has his reputation and career on the line,” says Anh.

By now everyone knows my opinion of censorship—the cowardly business by which the powerful lie to the weak in order to protect their self-interest. I have no need to repeat myself.

“You shouldn’t be too direct with Vinh,” says Anh. “He was acting on directions from the publisher.”

“You should also know that your book is a living thing,” says Giang. “It can be published again, with material that was cut in the first edition added back in later editions.”

I assure Anh and Giang that I will do my best not to offend anyone. They know that an uncensored Vietnamese version of my book will be released later on the web.

“Right now we have no standards in Vietnam,” says Giang. “We don’t know our rights, and we don’t know from what direction the censorship is coming. But our system is changing. We hope you understand that we can improve. We can do better. We are learning how to function in the world of international publishing.”

“If your book is republished, we want to put back in the details that were cut,” he says. “You have a positive perception of Vietnam. People know this. So we’re asking for you to be patient. Give us some time to work things out. People appreciate you as an expert on Vietnam, a critic, sometimes a tough critic, but a fair one. Vietnamology—maybe that’s the right word for what you do.”

“How many ‘hard’ books do you publish each year?” I ask.

“In our career we are always working with difficult books,” says Anh. “This comes with the territory. But your book was a special case. It was the most difficult. I wanted to give up. I thought it was hopeless. I’m hot headed, and this was just too hard. I threw up my hands. ‘This book is never going to be published!’ I said. But my colleagues are more patient than I am. ‘Wait,’ they told me. ‘There is still a chance.’ It was thanks to Giang and Thu Yen that your book saw the light of day. They were patient. They persisted.”

“I felt like a hostage between two warring armies,” says Anh. “I was being fired on from two directions. The author was resisting cuts. The censors were demanding cuts. There are authors who know how this system works, Milan Kundera for example. He has lived under censorship. When we published his books, he understood our problems and agreed to let us do what we had to do. It would have been helpful if you had been more reassuring.”

“On behalf of the publisher, we want to tell you that we’re happy your book has been published,” says Giang. I suspect he’s feeling sorry about my having been compared unfavorably to Milan Kundera. Actually, I’m amused that a refugee from communist Czechoslovakia would prove tractable to being censored in communist Vietnam.

“This is not the first time that Vietnam and the United States have engaged in difficult negotiations,” I say. Anh and Giang appreciate the joke. “I’m glad we arrived at a happy conclusion.” We shake hands, and then I am asked to sit at Anh’s desk to sign copies of my book for members of Nha Nam’s staff. Apparently, everyone in the company wants a copy—perhaps before the book disappears from the shelves. All throughout lunch hour people keep drifting into Anh’s office with yet more copies for me to sign.

Part 7: Perfect spy?

This sixth installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 9, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

2 Feb 2015

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship begins publishing a serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

These are dark days in Vietnam, as the courts decree long prison terms for writers, journalists, bloggers, and anyone else with the temerity to criticize the country’s rulers. The brief efflorescence of Vietnamese literature that followed the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989—known as doi moi, or the Renovation movement—is long gone. After twenty years of black pens and prison, the censors have wiped out an entire generation of Vietnamese writers, driving them into silence or exile.

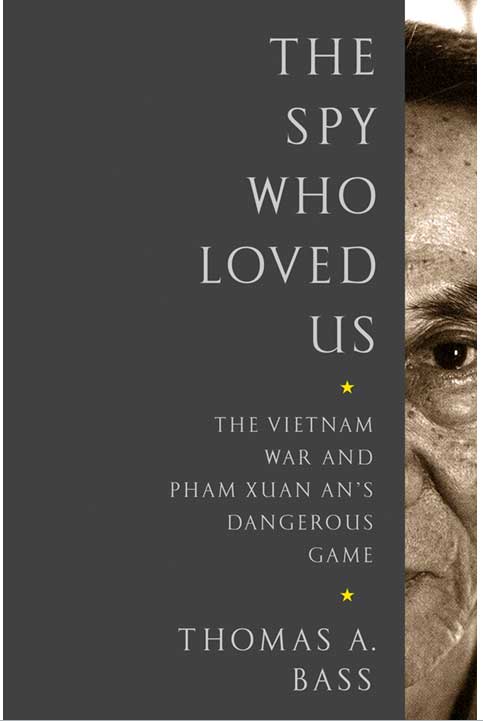

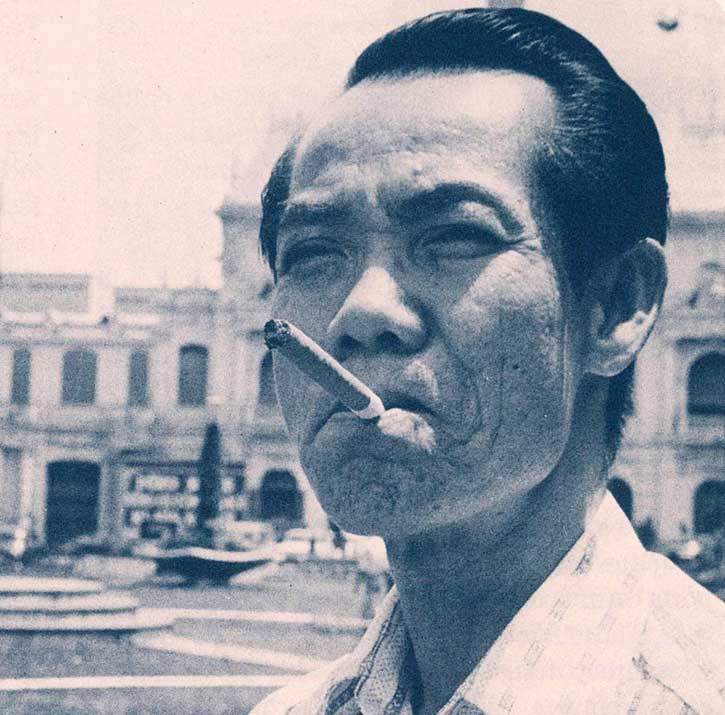

I myself have spent the last five years fighting with Vietnam’s censors, as they busied themselves cutting, rewriting, and then blocking from publication a Vietnamese translation of one of my books, The Spy Who Loved Us (2009). Based on a New Yorker article published in 2005, the book tells the story Pham Xuan An, the South Vietnamese journalist, whose remarkable effectiveness and long-lived career as a spy for the North Vietnamese communists—from the 1940s until his death in 2006—made him one of the greatest spies of the twentieth century. Trained in the U.S. as a journalist and using his profession as his cover, An worked as a correspondent for Time during the Vietnam war and served briefly as the magazine’s Saigon bureau chief. Charged with drawing battlefield maps, following troop movements, and analyzing political and military news, An leaked invaluable information to the North Vietnamese Army.

After the war, the victorious communists made An a Hero of the People’s Armed Forces and elevated him the rank of general. He is a natural subject for a biography, and, indeed, six have already been published, including another work in English by Georgia State University historian Larry Berman. Called Perfect Spy (2007), the book characterizes An as a patriot, a strategic analyst who observed the war from afar, until he happily retired to his living room, where he entertained a stream of distinguished visitors, from Morley Safer to Daniel Ellsberg.

My own account of An’s life is more troubling. I concluded that this brilliant raconteur developed a second cover as a spy. Claiming to be a friend of the West, an honest man who never told a lie (although his whole life was based on subterfuge), An had worked for Vietnamese military intelligence, not only throughout the Vietnam war, but also for thirty years after the war. At the same time, Vietnam’s northern power brokers distrusted this wise-cracking southerner who was outspoken in his attacks on the corruption and incompetence of Vietnam’s communist government. An’s rise in military rank was slow and begrudging, and he had been kept under police surveillance for years. The Vietnamese government might initially have been pleased by the prospect of publishing not one, but two, American-authored books on their “perfect spy,” but the longer the censors squinted at my version of An’s life, the more nervous they got, and the more the story had to be chopped and rewritten before it could be approved for publication.

After rejecting offers to translate my book from several publishers, including the People’s Public Security Publishing House (an official arm of Vietnam’s Ministry of Public Security) and the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism (one of the country’s largest censors), I signed a contract in July 2009 with Nha Nam, a respected publisher whose list of translated authors ranges from Jack Kerouac and Annie Proulx to Umberto Eco and Haruki Murakami. Nha Nam is an independent publisher, one of the few in Vietnam not affiliated with a ministry or other state censor. Nha Nam is occasionally fined for publishing “sensitive” books, and sometimes their titles are pulled from the shelf and pulped. Only later would I learn that Nha Nam’s status as an independent publisher does not guarantee its independence, but to their credit, the company has kept me apprised of every move made over the past five years to censor The Spy Who Loved Us.

Many authors ignore their books in translation. They delegate the sale of subsidiary rights to their agents and barely glance at the texts that arrive later in German or Chinese. I planned something different for my Vietnamese translation. I suspected it would be censored and wanted to track the process. I asked my agent to write into my contract a clause stating that the book would not be published without my prior consent and that I had to be consulted about changes made to the manuscript. Other clauses wired the book like a literary seismometer. I wanted it to record the work of the censors, to register their preoccupations and anxieties, so that by the end of the day I would know what the Vietnamese government feared and wanted to suppress.

The process of translating my book into Vietnamese began in March 2010, when I received an email saying, “I am Nguyen Viet Long of Nha Nam company, now editing the translation of The Spy Who Loved Us. I should like to correspond with you in regard to the translation.”

Long begins by asking if I know the correct diacritical marks for the name of Pham Xuan An’s grandfather. These are missing in English but important in Vietnamese, and I appreciate his attention to detail. Unfortunately, the rest of his email adopts a more aggressive tone. “You make some mistakes,” he writes, before correcting a laundry list of items. Many of these mistakes are not really mistakes, but questions of interpretation or judgment or matters of dispute in the historical record. They are the Vietnamese equivalent of inside baseball, arcane tidbits good for keeping scholars dancing on pinheads.

For example, did Jean Baptiste Ngo Dinh Diem (the first president of the Republic of Vietnam) become a provincial governor at the age of twenty-five? This depends on the day he was born, which is not an easy question to answer. People in Vietnam customarily fudge their birth dates, a practice recommended for scaring away demons, improving astrological signs, and attracting younger mates. An obscure item for an American author is apparently a big deal for the Vietnamese. If one assumes that Ngo Dinh Diem was an American puppet, a running dog for the imperialist invaders, then the last thing one wants to do is credit him with youthful accomplishment. Hence, one denies that he was the youngest governor in Vietnamese history and complicates the issue so extensively that it becomes easier simply to drop the claim.

Responding to a query from my literary agent, Long on March 15 writes, “There will be (absolutely) censorship, the book is sensitive. But please do not worry. We will keep talking to the author and will do our best to protect as much as possible the wholeness of the book.”

Long is trying to rush the book into print by April 30th—the auspicious day marking the end of the Vietnam war. After my agent reminds him that he is contractually obligated to show me the translation of the book before it can be published, Long misses the first deadline, and then he misses more deadlines, until, finally, six months later, in September 2010, I receive a copy of the galleys. The first thing I notice is an unusual number of footnotes scattered throughout the text, in a book that originally had no footnotes. I have enlisted a coterie of friends—academics, translators, an ex-CIA agent, and a former U.S. diplomat and his Vietnamese wife—to review the translation. They come back to me with sobering news. Apparently, many of the footnotes begin by saying, “The author is wrong.” Then they correct my “mistakes.”

Clearly, I have misunderstood the function of Vietnamese editors. Even before my book goes to the real censors—the chaps who control Vietnam’s publishing licenses—it has to be massaged in-house. Long will do the first whack, and the more efficiently he prunes, the more appreciated he will be by the state officials who can cap their black pens and turn to censoring more important things.

Part 2: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature

This first installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 2, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Feb 2014 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Vietnam

Le Quoc Quan (Image: RFAVietnamese/YouTube)

The 30 month prison sentence for Vietnamese human rights lawyer and blogger, Le Quoc Quan, was today upheld by a Hanoi appeals court. Quan, who has frequently blogged about human rights violations by the government, was convicted in October 2013 on tax evasion charges. He has been arbitrarily detained since December 2012. A crowd of hundreds wearing t-shirts in support of Quan were present outside the court, while a European Union delegation, representatives from the United States and Canada and a small group of journalists were present at the trial. This is just the latest move in the Vietnamese authorities’ ongoing attack on dissent, free speech, free press and a free internet.

If you need to communicate with someone the Vietnamese government is interested in keeping an eye, it is always been useful to be careful. Phone conversations can be listened to. Meetings at houses could be watched. Protests are invariably filmed by government operatives. If you were going to, say, chat via Gmail’s chat function it should be switched to “off the record” to prevent a copy of the discussion being archived. Some unlucky people have seen their blog posts traced to the internet cafe they’ve later been arrested at. If you are a dissident you won’t be the only one the police are interested in; they’ll talk to your family, friends and employers, too. The latter they may ask to dismiss you.

It is Vietnam Ministry of Public Security conducts this surveillance work, while the Ministry of Information and Culture drafts many of the laws regarding internet usage and “abuse”. And it is most likely a unit within the MPS that is responsible for these, and earlier, malware attacks.

Much of the surveillance and intimidation is hardly new; similar operations took place during the Terror in the USSR. In fact, the CIA has compared the MPS with Russia’s KGB. The KGB of comrade days, however, never had to deal with the vastness of the internet. The government owns every newspaper and printing press in the country, but it has few serious servers, making control of the internet difficult. It does not stop them from trying.

In January the Associated Press in Vietnam reported on malware attacks against one of its journalists, against an American-Vietnamese blogger and against the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). These are certainly not the first of their kind but may have been the first directed against those on foreign shores. The private correspondence of Vietnamese-American blogger Ngoc Tu was posted on her blog after someone — supposed, but not verified to be the Vietnamese government — sent her an email with a link that installed malware and key logging software giving the sender access to her password and her email account. The Associated Press reporter was a sent an email purportedly from Human Rights Watch with a link to a ‘white paper’ on human rights.

Vietnam’s internet history: Enthusiasm and repression

Vietnam’s relationship with the internet has not been simple. The government has always been enthusiastic about the internet and the wholesale benefits it could, and has, brought to the nation. Though classified as an “enemy of the internet” by Reporters Without Borders for its blocking of websites and arrests of bloggers and journalists, Vietnam’s communist government has done an awful lot to ensure good internet access.

But the country’s vibrant internet culture is a direct result of government guidance and intervention. Vietnam has long valued literacy and learning and according to Professor Carlyle Thayer at the Australian Defence Force Academy, the government believed that the “knowledge era” was key to the nation’s economic development. The internet helped to provide that and greater world integration, something they have been increasingly keen for since Doi Moi in 1986 when the country began a period of economic renovation, shunning its former isolationist politics.

Twenty years ago the Vietnam Communist Party (CPV) noted three dangers facing the country: corruption, deviation from the socialist path and falling behind. The internet was seen a perfect way to engage more with the world. A 2011 report by market research firm Cimigo, headquartered in Ho Chi Minh City, says: “Vietnam has seen a more rapid growth of the internet over the last few years than most other countries in the region and is one of the fastest growing internet countries in the world… Since the year 2000, the number of internet users in Vietnam has multiplied by about 120.”

However, the government misjudged, believing control to be easy, and circumventing its block beyond the ken of its citizens.

Putting the genie back in the bottle

There are three main laws bloggers, activists and others the state dislikes are charged under. Criminal Code Article 88 relates to “conducting propaganda against the state”. This is the one most often used — both draconian and helpfully vague. Then there is Article 258, relating to “abusing democratic freedoms”, and Article 79 covering “activities aimed overthrowing the Communist Party of Vietnam and People’s Socialist Republic of Vietnam”.

However there have also been numerous internet laws drafted, largely aimed at keeping citizens’ net activities restricted to useful research or harmless entertainment. An August 2001 law imposed “stringent” controls and required net cafe owners to report breaches to relevant authorities and to collect ID from their users. An August 2005 law criminalised using the internet to oppose or destabilise the state, security, economy or social order, infringe on the rights of organisations or individuals, or mess around with Domain Name System (DNS) settings — something many Facebook users started doing in 2009. In October 2007 the Ministry of Information and Culture issued a decision requiring all businesses to obtain a license before setting up a website. This has stymied growth in some ways, as it is only now that businesses are as present online as individuals.

In August 2008 Decree 97 made it illegal to “abuse” the internet to oppose the government. What got more attention was Circular 7, restricting bloggers to cover only personal, not political, topics. At the time blogging was a favoured pastime in Vietnam, Yahoo! 360 the favoured platform. Interest in blogging and blogs in general has since waned significantly. According to Cimigo, in 2009 40 per cent of internet users visited blogs and 20 per cent blogged themselves. By 2011 those numbers had halved as people increasingly moved to social media sites like Facebook.

It was the quiet block of Facebook in 2009 that caught the world’s attention. The government never mentioned a ban publicly though a purported scan of instructions to ISPs to block the site did rounds online. As the government never said much, Vietnam’s legion of Facebook users simply muttered something about “technical problems” as they “fixed” the DNS settings to access the site.

What led to the Facebook block was the organising between previously disparate groups against Chinese-run bauxite mines in the Central Highlands of Vietnam — an already ecologically and politically sensitive area. Catholics, activists, environmentalists and anti-China activists all united via Facebook to protest the mines. In 2010 the government tried to launch its own social networking site (which led to headlines such as ‘In Communist Vietnam, State Friends You’), go.vn, where users had to provide their full names and ID card details, but could also “friend” communist luminaries. The Minister for Culture and Information Le Doan Hop praised the site’s usefulness for young people and promotion of “culture, values and benefits”.

In 2010 came a decision requiring all public hotels to install Green Dam monitoring software. Theoretically it allowed the government to see what was being looked at, possibly by whom and take appropriate steps. In fact decision 15/2010/QD-UBND was something of a paper tiger; many pointed out how such a piecemeal and scattershot approach would have limited utility and could be wholly circumvented by any serious activist, though rights organisations took the appropriate potshots as a matter of course.

In 2010 a ban was put in place, ostensibly on all online gaming between 10pm and 6am, to combat gaming addiction. However, it was never fully possible to enforce thanks to most popular games being hosted by overseas servers.

The most recent attempts at curbing net use via legislation has been Decree-Law 72 on Management of the internet which formally came into effect in September 2013. Like many laws it is confusing and vague enough to be useful for any enthusiastic government prosecutor. Among other things it banned the sharing of news online. Or, rather, it banned the aggregation of news onto websites. The government took the time to publicly respond to the flurry of foreign concern and the head of the Ministry of Information and Culture’s Online Information Section protested to Reuters that the law did not violate any of Vietnam’s human rights commitments. “We will never ban people from sharing information or linking news from websites,” he said, arguing it had been misinterpreted.

There has been talk that Decree 72 was also designed to protect intellectual property, as violations have long been problematic and go far beyond dollar copies of new Hollywood films on DVD. One of the things 72 supposedly sought to do was prevent websites re-posting news from its original source with no attribution and thus make things easier for news sites whilst also laying groundwork for membership of the Trans Pacific Partnership in regards to intellectual property protection.

The more interesting requirement was that ISPs locate servers, or at least one, within Vietnam and deliver information on users to the government, rather as internet cafes have been required to do. They were also required to take down anything contravening laws. However Vietnam’s most trafficked sites do not have servers within Vietnam and with such new laws do not entirely see the point, either. Indeed there are not many substantial servers located there at all, and bloggers who fear the law usually host their blogs overseas in any case. Should the government instruct local ISPs to block say, Google, many will simply respond again to “technical difficulties” by readjusting their settings.

Peaceful evolution, draconian repression

The threat of peaceful and not so peaceful evolution hangs heavily over the heads of those in power in Hanoi.

Vietnam is regularly excoriated for its human rights record which generally means the way the nation locks up its dissidents, bloggers, religious leaders. Even US President Barack Obama made mention of blogger Dieu Cay’s ongoing detention, ostensibly for tax reasons.

According to Human Rights Watch there were at least 63 political prisoners convicted in Vietnam last year. And yet, as Professor Thayer said in a 2011 paper: “Great effort is put into monitoring, controlling and restricting Internet usage. The enormity of resources devoted for these purposes contrasts with the comparatively small number of political activists, religious leaders, and bloggers who have been arrested, tried and sentenced to prison.”

Though the numbers have increased since the above was written there is still little mass organising in this area, and large scale protests tend to be over more concrete issues: workers’ rights and wages or land grabs. However those considered potentially subversive are closely monitored, watched by both a physical presence and an online one.

Actual harassment of bloggers and their families has been common over the years. Most famously, mother of Vietnamese blogger Ta Phong Tan set herself on fire outside the Bac Lieu People‘s Committee building in the Mekong Delta in July 2012, in protest at the way her daughter had been treated.

Within the MPS are units that monitor all forms of communication and there are records of the country purchasing more complicated surveillance equipment. According to the same 2011 paper by Professor Thayer, Vietnam by 2002 had the Verint call monitoring system. Verint, a US company, supplies over 150 nations and 10,000 organisations with varied forms of security and monitoring equipment.

China in the 1990s also offered technical assistance to “monitor internal threats to national security” to the General Department II. The military also collects intelligence related to national security and with attention paid to those, abroad or within Vietnam, who “plot or engage in activities aimed at threatening or opposing the Communist Party of Vietnam or the Socialist Republic of Vietnam”.

General Department II not only, arguably, watched dissidents but also tapped senior party officials in an incident of usually opaque factionalism that later came to light.

There have been many attacks against varied blogs and websites; 16 starting in 2009 and intensifying in April of the next year. Varied activists came under fire: Catholics discussing land issues — there have been ongoing spats between Catholics and the state over land grabs — as well as environmentalists and political agitators. Sites allied to the anti-bauxite movement were also hit. IP addresses were allegedly traced back to within Vietnam and to addresses connected to the military. The attacks, verified by McAfee and Google, were botnet attacks where spyware hid in seemingly innocuous Vietnamese language keystroke software (though a Romanised alphabet Vietnamese has 29 letters and many diacritics). Neel Mehta, a security expert with Google, wrote in a blog post that: “While the malware itself was not especially sophisticated, it has nonetheless been used for damaging purposes.”

Vietnam joining the “technology race”?

That Vietnam has taken up the internet quickly and with great passion is beyond dispute but there are still gaps in the industry. Everyone may be using Google but few local businesses are profiting from the web and mobile boom.

Bryan Pelz, an IT developer, says there is “no means for direct monetization”.

“The banking industry and regulatory environment hasn’t taken strong steps to lay the groundwork for easy online payments. Essentially nobody has credit cards. If you’re building a website and hope to charge users or make a living off of advertising, it’s a tough road in Vietnam.”

And despite talented hackers and software engineers — Flappy Bird was designed by a Vietnamese engineer — with experience and skill comparable to the rest of Asia, software isn’t considered a hugely lucrative field, according to Pelz.

Of those aged 15 – 24, according to Cimigo, 95 per cent are online and spend over two hours each day on the web, via internet cafe, desktop or phone. Ninety five per cent use it for news. Google remains the top rated site in Vietnam, followed by local entertainment hub Zing. News sites Dan Tri and Tuoi Tre also feature, as does Yahoo!, Facebook and YouTube.

Last year a Russian-backed challenger to Google called Coc Coc (knock knock) opened shop. It has aimed to take some of Google’s 97 per cent market share, the reasoning being that Google had no offices in Vietnam and did not have algorithms well written enough to understand Vietnamese well. Unlike other startups it was backed with serious investment and a staff of over 300, according to the AP.

A recent article in The Atlantic reported that Vietnam’s Ministry of Science and Technology has sponsored something called the Silicon Valley Project which aims to push Vietnam to be more than a simple producer of electronic parts (Intel has a 1 billion USD plant in the country) to a tech powerhouse with a strong startup industry and innovative firms. The recent success of Flappy Bird — one of the most downloaded apps ever — is seen as evidence of Vietnam’s larger potential.

Indeed the Silicon Valley Project’s mission statement is not dissimilar to the Communist Party’s mid-1990s ideas about the upcoming “knowledge era”: “This is the time for Vietnam to join in the technology race. Countries which fail to change with this technology-driven world will fall into a vicious cycle of backwardness and poverty.”

This government-backed and sanctioned creativity and entrepreneurship has been lauded, though it’s also been pointed out how it may rather clash with many of the internet restrictions set out in varied laws, such as Decree 72. Of course Vietnam’s ministries do not always march in-sync and what the Ministry of Information and Culture believes to be good may clash with a more pro-tech Ministry of Science and Technology.

The confirmation today that Le Quoc Quan is facing 30 months behind bars, does not bode well for the future of internet freedom in Vietnam.

This article was published on 20 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom, Vietnam

(Photo: Shutterstock)

Vietnam has so far this year locked up more internet bloggers than in 2012. Vietnamese bloggers were therefore quick to react when, along with China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Algeria and Cuba, the communist country was elected to the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) for 2014-2016 term by creating and launching a new instrument for free expression: the Network of Vietnamese Bloggers (NVB).

The network aims to ensure that the Vietnamese government implements its obligations and commitments to the UNHRC through actions rather than mere political statements. Stating that, as Vietnam’s membership to the UNHRC means that all of its 90 million citizens are now members of the Council, the NVB will strive to uphold core values in the promoting and protection of human rights.

In order to do this it believes that Vietnam should:

- Agree to the 7 UN requests not yet met by the Vietnamese government which would allow UN delegates to visit Vietnam to investigate alleged human rights violations,

- End torture, cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment of any and all Vietnamese citizens,

- Release those currently imprisoned solely for peacefully exercising their freedom of expression and other rights based on core and universal values of UN treaties,

- Repeal vaguely-worded laws and decrees which are arbitrarily interpreted,

- End the state monopoly on media and publishing, ensure that all individuals and organisations are entitled to establish media agencies and publishing house,

- Remove firewalls that bar users accessing social media networks.

Chi Dang, Director of Overseas Support for the Free Journalist Network in Vietnam, stated that it was crucial that the launch of the network had international support as this has “proven to provide effective protection for our bloggers on the ground”.

The launch of the network will coincide with the International Human Rights Day on December 10.

This article was published on 16 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org