15 Apr 16 | About Index, Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, News and features

Words by Alessio Perrone and Sean Gallagher

Photos: Sean Gallagher

“I invite people like this: I just say – you paint now.” That’s how it works with street artist Murad Subay.

His murals grew from the frustration he felt as his homeland, Yemen, descended into chaos and factionalism. Amid the destruction and anger, Subay picked up his brush. With friends, he went out into the streets and began painting in broad daylight. Days passed, then people from the community joined him. All of them driven by their desire for peace amid Yemen’s civil war.

Since 2011 he’s created campaigns to encourage Yemenis to express their outrage at what their country has become. He and his collaborators have coloured walls, named the disappeared and marked ruins.

He always works during the day. It’s always part performance, part collaboration. Thursday 14 April was no different. Only the location had changed.

For his first mural outside Yemen, Subay took his brushes and paint to the corner of Hackney Road and Cremer Street to send a pointed message about the international community’s lack of humanity, especially toward his homeland. Even dogs are better than some of the global institutions and structures.

In London, to receive the 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award for his work, which Subay stressed is for Yemen. His acceptance speech was dedicated to the “unknown people who struggle to survive”.

Invited by Jay, the community curator of Art Under the Hood, Subay set up his equipment — with the help of new friends — and began transforming a hoarding into his vision using stencils he had laboured over since arriving on Saturday.

“I’m doing a sun dance.”

“I’m not the type of artist who zones out and thinks this is precious. It’s an ordinary thing for me”

“How long will it take for it to dry?”

“In Sana’a, three minutes!” Then a few seconds later “Here, I don’t know”

“Do you want me to do anything”

“Yes of course. Come here”

“Welcome to the holy state of Hackney, my friend. This is not a borough, not a city, it’s a state.”

“I’ve worked on these stencils from time to time for four days. It’s hard to say how long it takes. Sometimes it takes three, four hours, other times five … Depends on what I do”

“First, try it on the cardboard to see how strong or light it is. Then press in the shape, light, not strong. Keep it at an angle close to the margins, so you can make sure you don’t spray outside the shape. Then perpendicular in the middle. Keep it light, light!”

“Can I have a go?” a young woman asks.

“Yes of course!”

She stops for a moment, hesitant. Then she ends up staying until the very end. And in the end, Subay gives her, Éléa, the stencils when he finishes the mural.

“Do you paint?”

“A bit”

“Not a bit, you have to paint a lot! Painting is beautiful.”

“They have artists in Yemen? First time I hear that!”

“You know how to spray right? Come and learn a bit!”

“When I started out, I was alone, and I did it all in one week. I am slow. In the beginning, I never thought people could join. But then they did. They say: ‘Oh look, the artist!’ And they join”

“These stencils, I made in Yemen. I staged a photo, printed it, then cut it out. That chained man is one of my relatives. He’s a very nice person. He jokes a lot and loves painting. I really like him. We work together a lot, on street art of course but also many different things.”

“It’s all about how the man is suffering. He’s not just Yemen or anybody in particular. It could be any man. The dog is trying to help, and is showing more kindness then the other man. The dog shows that it’s possible to help out, but the other man doesn’t want to do anything.”

07 Nov 16 | Awards, Fellowship 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] Winner of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award, artist Murad Subay uses his country’s streets as a canvas to protest Yemen’s war, institutionalised corruption and forced “disappearings”.

Winner of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award, artist Murad Subay uses his country’s streets as a canvas to protest Yemen’s war, institutionalised corruption and forced “disappearings”.

Since beginning a street art protest in 2011 Subay has launched five campaigns to promote peace and encourage discussion of sensitive political issues. All his painting is done in public during the day and he encourages fellow Yemenis to get involved. Subay has often been targeted by the authorities, painting over his works or restricting him from painting further.

“I found that the soul of the Yemeni people was broken because of war… I found that the buildings and the streets were full of bullets, full of damage. So I went on Facebook and said I would go on to the streets to paint the next day and I did.” — Murad Subay

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1501491116489-589cb4f1-c150-10″ taxonomies=”8196″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

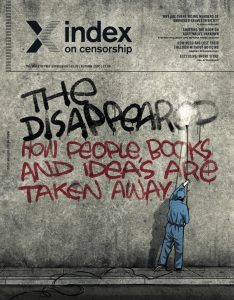

17 Sep 20 | Volume 49.03 Autumn 2020, Volume 49.03 Autumn 2020 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The brave stand up when others are afraid to do so. Let’s remember how hard that is to do, says Rachael Jolley in the autumn 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.”][vc_column_text]

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.

The US Supreme Court justice may be a popular icon right now, but when she set her course to be a lawyer she was in a definite minority.

For many years she was the only woman on the court bench, and she was prepared to be a solitary voice when she felt it was vital to do so, and others strongly disagreed.

The dissenting voice and its place in US law is a fascinating subject. A justice on the court who disagrees with the majority verdict publishes a view about why the decision is incorrect. Sometimes, over decades, it becomes clear that the individual who didn’t go with the crowd was right.

The dissenting voice, it seems, can be wise beyond the established norms. By setting out a dissenting opinion, it gives posterity the chance to reassess, and perhaps to use those arguments to redraft the law in later times.

Bader Ginsburg was the dissenting voice in the case of Ledbetter v Goodyear – in which Lily Ledbetter brought a case on pay discrimination but the court ruled against her – and in Shelby County v Holder on voting discrimination, an issue likely to be hotly debated again in this year’s US presidential election. Bader Ginsburg’s opinions may not have been in the majority when those cases were heard but the passage of time, and of some legislation, proved her right.

The dissenting voice in law is a model for why freedom of expression is so vital in life. You may feel alone in your fight for the right to change something (or in your position on why something is wrong), but you must have the right to express that opinion. And others must be willing to accept that minority views should be heard – even if they disagree with them.

Fight for the principle, and when the time comes that you, your friends or your neighbours need it, it will be there for you.

Right now, writers, artists and activists are standing up for that principle, not necessarily for themselves but because they feel it is right.

Sometimes they also bravely dissent when most people are afraid to speak up for change, or to disagree with those who shout the loudest.

Being different and on the outside is a lonely place to be, but the pressure is even greater when you know opposing an idea, or law, could mean losing your home or your job, or even landing in prison.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd0d0d”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The dissenting voice in law is a model for why freedom of expression is so vital in life.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As editor-in-chief at Index I have been privileged to work with extraordinary people who are willing to be dissenting voices when, all around them, society suggests they should be quiet. They smuggle out words because they think words make a difference. They choose to publish journalism and challenging fiction because they want the world to know what is going on in their countries. They often take enormous risks to do this.

For them, freedom of expression is essential. Murad Subay is a softly spoken Yemeni artist with a passion for pizza. He produced street art even as the bombs fell around him in Sana’a. Often called Yemen’s Banksy, Subay – an Index award winner – worked under unbelievably horrible conditions to create art with a message.

In an interview with Index in 2017, Subay told us: “It’s very harsh to see people every day looking for anything to eat from garbage, waiting along with children in rows to get water from the public containers in the streets, or the ever-increasing number of beggars in the streets. They are exhausted, as if it’s not enough that they had to go through all of the ugliness brought upon them by the war.”

Dissenting voices come from all directions and from all around the world.

From the incredibly strong Zaheena Rasheed, former editor of the Maldives Independent, who was forced to leave her country because of death threats, to regular correspondence from our contributing editor in Turkey, Kaya Genç, these are journalists who keep going against the odds. These are the dissenting voices who stand with Bader Ginsburg.

Over the years, the magazine has featured many writers who have stood up against the crowd. People such as Ahmet Altan, whose words were smuggled out of prison to us. He told us: “Tell readers that their existence gives thousands of people in prison like me the strength to go on.”

In this issue, we explore those whose ideas and voices – and sometimes, horrifically, bodies – are deliberately disappeared to muffle their dissent, or even their very existence.

Many people associate the term “the disappeared” with Argentina during the dictatorships, where we know about some of the horrific tactics used by the junta. Opposition figures were killed; newborn babies were taken from their mothers and given to couples who supported the government, their mothers murdered and, in many cases, dumped at sea to get rid of the evidence. The grandmothers of those who were disappeared are still fighting to bring attention to those cases, to uncover what happened and to try to trace their grandchildren using DNA tests.

Index published some of those stories from Argentina at the time because Andrew Graham-Yooll, who was later to become the editor at Index, smuggled out some of the information to us and to The Daily Telegraph, risking his life to do so.

We explore what and who are being disappeared by authorities that don’t want to acknowledge their existence.

Thousands of people who are escaping war and starvation try to flee across the Mediterranean Sea: hundreds disappear there. Their bodies may never be found.

It is convenient for the authorities on both sides of the sea that the numbers appear lower than they really are and the real stories don’t get out.

In a special report for this issue, Alessio Perrone reveals the tactics being used to cover up the numbers and make it appear there are fewer journeys and deaths than in reality.

The International Organisation for Migration’s Missing Migrants Project says that 20,000 people have died in the Mediterranean since records began in 2014, but many say this is an underestimation.

Certainly there are unmarked graves in Sicily where bodies have been recovered but no one knows their names (see page 30). The Italian government has, as we have previously reported, used deliberate tactics to make it harder to report on the situation and to stop the rescue boats finding refugees adrift near her boundaries.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#2a31b7″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”It is convenient for the authorities on both sides of the sea that the numbers appear lower than they really are and the real stories don’t get out.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Also in this issue, Stefano Pozzebon and Morena Joachín report on how Guatemala’s national police archives – which house information on those people who were disappeared during the civil war – is currently closed, and not for Covid-19 reasons (see page 27).

Fifteen years after the archive was first opened to the public, a combination of political pressure and a desire to rewrite history in the troubled nation has closed it. This is a tragedy for families still using it in an attempt to trace what happened to their families.

In Azerbaijan (see page 8), another tactic is being used to silence people – this time using technology. Activists are having their profiles hacked on social media and then posts and messages are being written by the hackers and posted under their names.

Their real identities conveniently disappear under a welter of false information – a tactic used to undermine trust in journalists and activists who dare to challenge the government so that the public might stop believing what they write or say.

This is my 30th and final issue of the magazine after seven years as editor (although I will still be a contributing editor), and it is another gripping one.

They smuggle out words because they think words make a difference.

Over the years, I am proud to have worked with the incredible, brave, talented and determined. We have published new writing by Ian Rankin, Ariel Dorfman, Xinran, Lucien Bourjeily, and Amartya Sen, among others. And it has been a privilege to work with the mindblowing, sharp, analytical journalism from the pens of our incredible contributing editors over the years, including Kaya Genç, Irene Caselli, Natasha Joseph, Laura Silvia Battaglia, Stephen Woodman, Duncan Tucker and Jan Fox, plus regular contributors Wana Udobang, Karoline Kan, Steven Borowiec, Alessio Perrone and Andrey Arkhangelsky.

These people do amazing work: their writing is ahead of the game and they bring together thought-provoking analysis and great human stories. Thank you to all of them, and to deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld.

They have told me again and again why they value writing for Index on Censorship and the importance of its work.

And because we believe that supporting writers and journalists is also about them getting paid for their work, unlike some others we have always supported the principle of paying people for their journalism.

Over the years we have attempted to go above and beyond, providing a little extra training when we can, translating Index articles into other languages, inviting journalists we work with to events, and introducing them to book publishers.

But just like the first time I ventured into the archives of the magazine, I am still amazed by what gems we have inside. We have recently reached our biggest readership to date, with hundreds of thousands of articles being downloaded in full, showing an appetite for the kind of journalism and exclusive fiction we publish.

Thank you, readers, for being part of the journey, and please continue to support this small but important magazine as it continues to speak for freedom.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is the former editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship’s autumn 2020 issue, entitled The disappeared: how people, books and ideas are taken away.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2020 magazine podcast featuring Hong Kong-based journalist Oliver Farry, who discusses the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in the region

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Winner of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award, artist Murad Subay uses his country’s streets as a canvas to protest Yemen’s war, institutionalised corruption and forced “disappearings”.

Winner of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award, artist Murad Subay uses his country’s streets as a canvas to protest Yemen’s war, institutionalised corruption and forced “disappearings”. Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]