Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

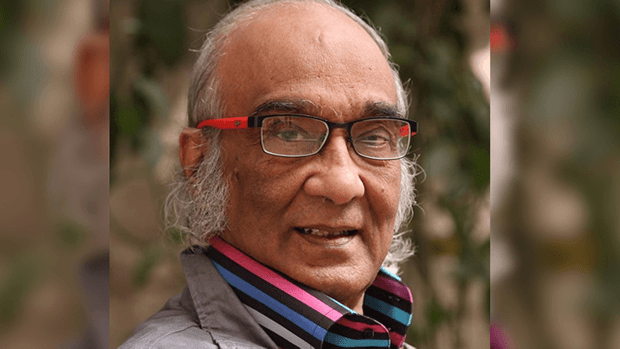

Shafik Rehman (Photo: Reprieve)

Anisul Huq

Minister for Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs

Government of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Secretariat, Building No. 4 (7th Floor) Dhaka-100

4 August 2016

Dear Mr Huq,

We are writing to you as international press freedom, freedom of expression and media advocacy groups about the ongoing detention of Shafik Rehman, an elderly journalist in custody in Dhaka, to set out several serious concerns about his treatment.

We were pleased to note that on Sunday 17 July 2016 the Supreme Court granted Mr Rehman’s request for leave to appeal his detention.

Detention without charge

Mr Rehman was arrested on 16 April 2016 and denied bail by the High Court on 7 June 2016. After more than three months in detention, he has still not been charged with any crime.

He is being investigated by the Bangladesh Detective Branch, who entered his house without a warrant, inexplicably posing as a camera crew, on the day of his arrest.

The detectives missed a deadline on 16 June 2016 to submit a report to Metropolitan Magistrate SM Masud Zaman in Dhaka outlining the alleged case against Mr Rehman. The court extended the deadline until 26 July 2016, despite the fact that the First Information Report in this case was initially filed in August 2015 and the investigation period in the case has expired. On 26 July 2016, the police once again missed the deadline to submit their investigation report and a further deadline has now been set for 30 August 2016 – more than 100 days after his arrest.

Under international law, the Bangladesh authorities have a duty to promptly inform Mr Rehman of the nature of the case against him and either charge or release him. The delays in this case suggest that there is no evidence against Mr Rehman, and that he should be released.

Journalistic career

Mr Rehman is a professional journalist who has spent a lifetime working for freedom of expression. We are concerned that his arrest represents an attack on press freedoms and forms part of a worrying trend in Bangladesh. At the time of his arrest, Mr Rehman was editor of the popular monthly magazine Mouchake Dhil, with experience as a TV host and producer. Previously, he has worked for the BBC and edited Jai Jai Din, a mass- circulation Bengali daily.

The arrest of journalists like Mr Rehman raises concerns about the state of press freedoms in Bangladesh, where several prominent editors have been arrested in recent years.

Denied bail

Mr Rehman is an elderly man in poor health. He spent the first weeks of detention in solitary confinement, without a bed. His health deteriorated and he was rushed to hospital.

His family are seriously concerned about his health failing in prison, and he has missed important medical appointments while on remand.

There are therefore strong compassionate grounds for releasing Mr Rehman on bail, while any evidence (if there is any at all) can be gathered without jeopardising his health.

We hope that Mr Rehman’s appeal will be an opportunity for the Court to take stock of the serious concerns about the case against Mr Rehman and about his health and well-being while he remains in custody.

We appreciate you hearing our concerns and are grateful for swift action to guarantee Mr Rehman’s prompt release.

Yours sincerely,

Reprieve | Index on Censorship | International Federation of Journalists | Reporters Without Borders | Adil Soz – International Foundation for Protection of Freedom of Speech | Afghanistan Journalists Center | Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain | Bahrain Center for Human Rights | Canadian Journalists for Free Expression | Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility | Foro de Periodismo Argentino | Free Media Movement | Independent Journalism Center – Moldova | Institute for the Studies on Free Flow of Information | International Press Institute | Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance | Media Foundation for West Africa | National Union of Somali Journalists | Norwegian PEN | Pacific Freedom Forum | Pacific Islands News Association | Pakistan Press Foundation | Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA | PEN American Center | Public Association “Journalists” | Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

Via post to:

High Commission for the People’s Republic of Bangladesh

28 Queen’s Gate

London

SW7 5JA

Add your voice: Call on Bangladesh to free British journalist Shafik Rehman https://t.co/sslk4GsISX @Reprieve pic.twitter.com/CpXvOWpQ6U

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) August 10, 2016

On Friday night, security forces stormed Zaman, the widest-circulating Turkish newspaper. Though many Turkish news outlets studiously avoided covering the raids, the screens of international news channels were full of images of Turkish police using tear gas and water cannon against protestors trying to protect their paper. Particularly striking were the injuries to young women wearing Islamic headgear, the very segment of the community, which the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) once vowed to defend.

On Friday night, security forces stormed Zaman, the widest-circulating Turkish newspaper. Though many Turkish news outlets studiously avoided covering the raids, the screens of international news channels were full of images of Turkish police using tear gas and water cannon against protestors trying to protect their paper. Particularly striking were the injuries to young women wearing Islamic headgear, the very segment of the community, which the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) once vowed to defend.

The seizure of a news organisation by placing it into court-appointed administration is not trivial. The Zaman group employs some two thousand people, runs a nationwide network of correspondents and puts out an English language daily, Today’s Zaman, which has an international following on the web. It is impossible to imagine a court in any country with the slightest pretension of being democratic acting with such impunity.

The final headline of the independent version of Zaman was that there could be no legal basis for the takeover. Indeed, Article 30 of the Turkish Constitution reads: “A printing house and its annexes, duly established as a press enterprise under law, and press equipment shall not be seized, confiscated, or barred from operation on the grounds of having been used in a crime.” (As amended on May 7, 2004; Act No. 5170)”

It is no secret that Zaman demonstrated fidelity to the movement associated with the exiled cleric, Fethullah Gülen. The paper once supported the rise of AKP but in recent years has been a bitter critic. The legal document, which placed Zaman’s parent company into court-appointed administration, relies on the testimony of an anonymous witness who maintains that the editorial policy was dictated by what it calls the Fethullah Terror Organisation (FETÖ in its Turkish acronym). This in turn is guilty of conspiring with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). It is enough to point out that the existence of FETÖ is at best hearsay, at worst the invention of subeditors in the pro-government press – never mind that Zaman itself once took a more hawkish line towards the PKK than the government itself.

It is no secret that Zaman demonstrated fidelity to the movement associated with the exiled cleric, Fethullah Gülen. The paper once supported the rise of AKP but in recent years has been a bitter critic. The legal document, which placed Zaman’s parent company into court-appointed administration, relies on the testimony of an anonymous witness who maintains that the editorial policy was dictated by what it calls the Fethullah Terror Organisation (FETÖ in its Turkish acronym). This in turn is guilty of conspiring with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). It is enough to point out that the existence of FETÖ is at best hearsay, at worst the invention of subeditors in the pro-government press – never mind that Zaman itself once took a more hawkish line towards the PKK than the government itself.

According to reports reaching P24, the prosecutor struggled to find a court which would accede to his request. The Zaman building is in the Bakırköy province of Istanbul and comes under its jurisdiction. However, the request in the Bakırköy court was refused. Finally another, more friendly court acceded to the prosecutor’s demand, even though it is dubious whether it had the competence to do so.

The paper may not be guilty of treason but is has been guilty of apostasy – of having turned its back on AKP and President Tayyip Erdoğan in particular. Since then the two have been in mortal combat. Loyalists to the Gülen movement and the Zaman group in particular pursued corruption allegations against leading government officials in December 2013.

By forcing Zaman’s takeover the government lays itself open to universal condemnation. Turkey, once a proud EU applicant, now plumbs the lower depths of global rankings of transparency and free expression. Sadder still, this does not seem to trouble it a jot.

“The timing is a slap in the face,” according to a diplomat quoted in The Financial Times. “The seizure came during a visit to Istanbul by Donald Tusk, the European Council president, and two days before Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, is to see Ahmet Davutoğlu, the Turkish premier,” the paper points out. Turkey now calibrates its place in the world not as a democratic standard bearer in a troubled part of the globe but as a buffer zone between Fortress Europe and a tide of Syrian refugees. This, it believes, gives it licence to get away with the murder of a newspaper.

In Turkey all eyes, government and opposition, are on the EU to see if Brussels is prepared to put expediency above principle and if European pubic opinion is prepared to see Ankara give up all pretence of democratic governance in exchange for grudging cooperation on Syria.

It is not just the timing of the EU summit, which is significant. The Constitutional Court recently gave the presidential office a swift kick in the shins with the release from pre-trial detention of the editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet newspaper along with his Ankara bureau chief. The high court ruled that the charges against them – that printing stories in a newspaper could correspond to treason – were essentially absurd. Since then, newspapers and ministers loyal to the president have been braying for the judges’ blood. The president himself has said he would neither respect nor abide by the high court’s decision and now appears even more determined to draft a new constitution which would allow him to do exactly that.

Not everyone in AKP supports this autocratic trend. There is a small wave of discontent from the old guard who believe a constitution that concentrates even greater powers in presidential hands is a dangerous step. These homegrown dissidents took quiet satisfaction in the court’s defence of Cumhuriyet. So one can see the raid against Zaman as the president re-asserting his authority against these pockets of resistance to one-man rule.

Turkey’s 1982 Constitution was prepared under conditions of martial law. It attempted to dictate a society in which the rights of citizen were subservient to the needs of the state. This rendered it anachronistic before the ink on the Official Gazette was dry. It has constantly been rewritten and there have been consistent demands that it be replaced.

Yet no one, not even in their wildest babblings, ever claimed the current Constitution was insufficiently authoritarian, or that it ceded too little power to the arbitrary whim of government, or that it failed to enshrine the Machiavellian principle that “might makes right”.

No one, that is, until now. As the ink on the printing presses of Turkey’s independent media run dry so too do hopes for the country’s future.

See also:

Statement: Index condemns seizure of Zaman

Sign our petition: End Turkey’s crackdown on press freedom

Letter: Writers and artists condemn seizure of Zaman news group

Reaction: Turkish court orders seizure of Zaman news group

Index on Censorship condemns the seizure by Turkey’s courts of the newspaper Zaman, one of the country’s highest circulation newspapers.

The move is the latest in a spate of attacks on the free press by the government, which has arrested and detained scores of journalists over the past 12 months.

Last month, Turkey’s authorities were forced to release journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül after Turkey’s Constitutional Court ruled that their rights had been violated by their arrest. Dündar, the editor-in-chief of the daily Cumhuriyet, and his Ankara bureau chief, Gül, had been held since the evening of 26 November. They are charged with spying and terrorism because last May they published evidence of arms deliveries by the Turkish intelligence services to Islamist groups in Syria. The charges have not been dropped and the journalists are awaiting trial.

Zaman said in a statement on Friday that administrators had been appointed to run the paper.

“We are going through the darkest and gloomiest days in terms of freedom of the press,” the organisation said.

The move highlights how far press freedom has deteriorated in Turkey in recent months. Index has recorded more than 10 press freedom violations over the past month alone and 203 verified violations since May 2014.

“With this move, Turkey has hit a new low for media freedom,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “We now need the international community to help pull it back from the brink by encouraging governments to speak out publicly against these actions instead of turning a blind eye to President Erdogan’s creeping authoritarianism.”

Ahead of the EU-Turkey meeting on migration next week, it is crucial for the EU to denounce the unprecedented crackdown on media freedom and remind Turkey of its obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights. Any agreement on migration should not undermine the fundamental rights of freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

The Paris and Cologne offices of a Turkish newspaper were attacked by supporters of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) last week. Zaman newspaper says that a group of nearly 15 masked PKK supporters entered its Paris office on 15 February, threatening employees and breaking furniture and computers. Meanwhile AFP has reported that arsonists torched the paper’s Cologne headquarters on the evening of the same day. The EU, USA and Turkey all classify the PKK as a terrorist organisation.