7 Jan 2016 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Statements, United Kingdom

When I started working at Index on Censorship, some friends (including some journalists) asked why an organisation defending free expression was needed in the 21st century. “We’ve won the battle,” was a phrase I heard often. “We have free speech.”

There was another group who recognised that there are many places in the world where speech is curbed (North Korea was mentioned a lot), but most refused to accept that any threat existed in modern, liberal democracies.

After the killing of 12 people at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, that argument died away. The threats that Index sees every day – in Bangladesh, in Iran, in Mexico, the threats to poets, playwrights, singers, journalists and artists – had come to Paris. And so, by extension, to all of us.

Those to whom I had struggled to explain the creeping forms of censorship that are increasingly restraining our freedom to express ourselves – a freedom which for me forms the bedrock of all other liberties and which is essential for a tolerant, progressive society – found their voice. Suddenly, everyone was “Charlie”, declaring their support for a value whose worth they had, in the preceding months, seemingly barely understood, and certainly saw no reason to defend.

The heartfelt response to the brutal murders at Charlie Hebdo was strong and felt like it came from a united voice. If one good thing could come out of such killings, I thought, it would be that people would start to take more seriously what it means to believe that everyone should have the right to speak freely. Perhaps more attention would fall on those whose speech is being curbed on a daily basis elsewhere in the world: the murders of atheist bloggers in Bangladesh, the detention of journalists in Azerbaijan, the crackdown on media in Turkey. Perhaps this new-found interest in free expression – and its value – would also help to reignite debate in the UK, France and other democracies about the growing curbs on free speech: the banning of speakers on university campuses, the laws being drafted that are meant to stop terrorism but which can catch anyone with whom the government disagrees, the individuals jailed for making jokes.

And, in a way, this did happen. At least, free expression was “in vogue” for much of 2015. University debating societies wanted to discuss its limits, plays were written about censorship and the arts, funds raised to keep Charlie Hebdo going in defiance against those who would use the “assassin’s veto” to stop them. It was also a tense year. Events discussing hate speech or cartooning for which six months previously we might have struggled to get an audience were now being held to full houses. But they were also marked by the presence of police, security guards and patrol cars. I attended one seminar at which a participant was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards. Newspapers and magazines across London conducted security reviews.

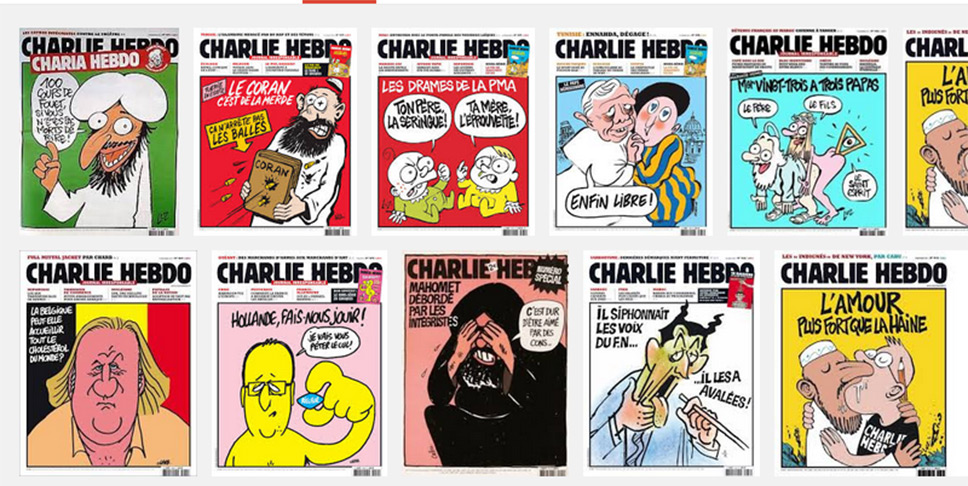

But after the dust settled, after the initial rush of apparent solidarity, it became clear that very few people were actually for free speech in the way we understand it at Index. The “buts” crept quickly in – no one would condone violence to deal with troublesome speech, but many were ready to defend a raft of curbs on speech deemed to be offensive, or found they could only defend certain kinds of speech. The PEN American Center, which defends the freedom to write and read, discovered this in May when it awarded Charlie Hebdo a courage award and a number of novelists withdrew from the gala ceremony. Many said they felt uncomfortable giving an award to a publication that drew crude caricatures and mocked religion.

Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom recorded 745 violations against media freedom across Europe in 2015.

The problem with the reaction of the PEN novelists is that it sends the same message as that used by the violent fundamentalists: that only some kinds of speech are worth defending. But if free speech is to mean anything at all, then we must extend the same privileges to speech we dislike as to that of which we approve. We cannot qualify this freedom with caveats about the quality of the art, or the acceptability of the views. Because once you start down that route, all speech is fair game for censorship – including your own.

As Neil Gaiman, the writer who stepped in to host one of the tables at the ceremony after others pulled out, once said: “…if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

Index believes that speech and expression should be curbed only when it incites violence. Defending this position is not easy. It means you find yourself having to defend the speech rights of religious bigots, racists, misogynists and a whole panoply of people with unpalatable views. But if we don’t do that, why should the rights of those who speak out against such people be defended?

In 2016, if we are to defend free expression we need to do a few things. Firstly, we need to stop banning stuff. Sometimes when I look around at the barrage of calls for various people to be silenced (Donald Trump, Germaine Greer, Maryam Namazie) I feel like I’m in that scene from the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels where a bunch of gangsters keep firing at each other by accident and one finally shouts: “Could everyone stop getting shot?” Instead of demanding that people be prevented from speaking on campus, debate them, argue back, expose the holes in their rhetoric and the flaws in their logic.

Secondly, we need to give people the tools for that fight. If you believe as I do that the free flow of ideas and opinions – as opposed to banning things – is ultimately what builds a more tolerant society, then everyone needs to be able to express themselves. One of the arguments used often in the wake of Charlie Hebdo to potentially excuse, or at least explain, what the gunmen did is that the Muslim community in France lacks a voice in mainstream media. Into this vacuum, poisonous and misrepresentative ideas that perpetuate stereotypes and exacerbate hatreds can flourish. The person with the microphone, the pen or the printing press has power over those without.

It is important not to dismiss these arguments but it is vital that the response is not to censor the speaker, the writer or the publisher. Ideas are not challenged by hiding them away and minds not changed by silence. Efforts that encourage diversity in media coverage, representation and decision-making are a good place to start.

Finally, as the reaction to the killings in Paris in November showed, solidarity makes a difference: we need to stand up to the bullies together. When Index called for republication of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons shortly after the attacks, we wanted to show that publishers and free expression groups were united not by a political philosophy, but by an unwillingness to be cowed by bullies. Fear isolates the brave – and it makes the courageous targets for attack. We saw this clearly in the days after Charlie Hebdo when British newspapers and broadcasters shied away from publishing any of the cartoons featuring the Prophet Mohammed. We need to act together in speaking out against those who would use violence to silence us.

As we see this week, threats against freedom of expression in Europe come in all shapes and sizes. The Polish government’s plans to appoint the heads of public broadcasters has drawn complaints to the Council of Europe from journalism bodies, including Index, who argue that the changes would be “wholly unacceptable in a genuine democracy”.

In the UK, plans are afoot to curb speech in the name of protecting us from terror but which are likely to have far-reaching repercussions for all. Index, along with colleagues at English PEN, the National Secular Society and the Christian Institute will be working to ensure that doesn’t happen. This year, as every year, defending free speech will begin at home.

21 Aug 2015 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

Lilian Lepère has filed a lawsuit against French media outlets for revealing where he was hiding during a standoff with the Charile Hebdo attackers. (Photo: YouTube / France 2)

Graphic designer Lilian Lepère hid under a sink for eight hours while the Kouachi brothers, Saïd and Chérif, on the run after attacking Charlie Hebdo, occupied the printing house where he worked in Dammartin-in-Goële (in the Seine-et-Marne region). Believing it was empty, the brothers hid in the factory for several hours before being killed by a special operations unit of the French armed forces.

While the designer was hiding, MP Yves Albarello (Les Républicains), during an interview with RMC radio, revealed Lepère was in the building. Television channels TF1 and France 2 repeated the information. The Kouachi brothers, who had smartphones and a radio, could have easily discovered Lepère’s presence.

French newspaper Le Parisien recently revealed that Lepère intends to sue RMC, TF1 and France 2 for revealing that he was hidden during the stand-off with the Kouachis. The newspaper reported that Lepère will contend in the suit that the media outlets put his life in danger. Last Thursday, 13 August, the Paris Public Prosecutor’s department opened an investigation.

This is not the first time French media has come under scrutiny for its treatment of the January attacks.

In February, the country’s broadcasting watchdog Conseil supérieur de l’audiovisuel (CSA) distributed warnings to TV and radio stations, noting that 13 media outlets revealed live on air that a confrontation had begun between the police and the Kouachi brothers. Considering this a “serious failure”, the CSA said that the reporting “could have had dramatic consequences for the hostages of the Hyper Casher in Porte de Vincennes”, where Amedy Coulibaly, an accomplice of the Kouachi brothers, was holding hostages at a supermarket. Coulibaly was demanding that the brothers be released. The CSA also blamed TV channels for revealing that people were hiding during the two hostage crisis that took place on 9 January.

The CSA listed the broadcasters’ failings, reproaching them:

• The broadcasting of images showing the policeman being shot by the terrorists

• The broadcasting of elements allowing the identification of the Kouachi brothers

• The disclosure of the identity of a person suspected to be a terrorist

• The broadcasting of images and information regarding an operation still under way, as hostages were still being held in Dammartin-en-Goële and in the Hyper Casher in Porte de Vincennes

• The announcement that a confrontation with the terrorists was taking place in Dammartin-en-Goële while Amedy Coulibaly was still entrenched in Porte de Vincennes

• The divulging of information regarding people hiding in the places where the terrorists had been entrenched, while the assaults had not yet taken place and the hostages’ lives were therefore still at risk

• The broadcasting of images of the assault in the Hyper Casher store Porte de Vincennes

At the time, TV and radio channels contested the CSA’s decision, writing, in a joint letter entitled “Information under threat” that, “The freedom of the press is a constitutional right. Journalists have a duty to inform with rigour and precision. The CSA blames us for having potentially breached public order or taken the risk to fuel tensions within the population. We dispute this.”

They added: “How is it possible to think that, in 2015, the CSA wishes to reinforce the control on an already regulated French broadcasting media while information circulates without constraint in the written press, on foreign channels, all social media and websites? Aren’t they placing us in a situation of inequality in front of the law?”

In a similar story that took place in March 2015, the six people who hid at the Hyper Casher, where Amedy Coulibaly killed four people, filed a complaint against an unknown person for putting their lives in danger. The complaint was directed at the media and specifically at BFMTV, Patrick Klugman, a lawyer representing the group, told Le Parisien. BFMTV revealed that a woman might of been hiding within the Hyper Casher.

“The disclosure of the presence of these people who were hiding, in the middle of a hostage crisis, is a failing that cannot remain unpunished, and all the more so because we knew that the terrorist was watching the TV channel. An information, even if it is accurate, must not put lives in danger”, Klugman said.

Speaking with Le Nouvel Obs, Christophe Bigot, a lawyer who specialises in media, explained that even if an investigation has been opened, because the story had stirred a lot of emotions at the time, Lilian Lepère’s complaint has little chance to succeed.

“The principle, when it comes to the press, is freedom of expression. It has precise limits determined by law, such as libel or the broadcasting of fake information likely to disrupt public peace. In this case, none of these limits can be pointed out. For the media, several complaints could nonetheless be an occasion to examine how to reconcile immediacy of information and ethics,” Bigot said.

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

Related:

• Targeted cartoonists show support for Charlie Hebdo

• Stand up for free speech. Publish Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons

• Don’t let free speech die

• How cartoonists responded to the attack on Charlie Hebdo

This article was posted to indexoncensorship.org on 21 August 2015

1 Feb 2015 | Events, mobile, News and features

A book event on “The Content and Context of Hate Speech – Rethinking Regulation and Responses” edited by Michael Herz and Peter Molnar (Cambridge UP 2012)

Hosts: The Rafto Foundation, Vivarta, Institute for Strategic Dialogue and Index on Censorship.

The attack on Charlie Hebdo dramatically increased the pressure on freedom of speech in all of Europe. How do we respond to audiences who do not recognize satire as a legitimate form of free expression, without increasing this pressure?

All are invited to this public discussion with leading thinkers and activists, starting with a reception including short slam poetry performances at 6 pm.

PANEL:

– Jodie Ginsberg, CEO Index on Censorship (moderator)

– Peter Molnar, free speech scholar, writer, slammer, radio host (CEU), Radio Forbidden)

– Rashad Ali, Director of CENTRI, Senior Fellow to ISD

– Timothy Garton Ash, Director of freespeechdebate.com, Oxford University

Where: Free Word Centre

, 60 Farringdon Road

, London, EC1R 3GA

When: Friday 13 Feb at 6pm

Tickets: Free entrance

14 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, France, News and features, Turkey

In October, Turkish cartoonist Musa Kart was the subject of a global solidarity campaign from his fellow artists. Kart was facing nine years in jail for insulting President Recep Tayyip Erodgan through a caricature for Cumhuriyet, where he commented on Erdogan’s alleged hand in covering up a high-profile corruption scandal. In response, his colleagues from around the world rallied in support of Kart, publishing their own #ErdoganCaricature on Twitter, and he was acquitted of the charges. This time, Kart is joining cartoonists in standing with Charlie Hebdo.

Cartoon courtesy Musa Kart

Kart told Index he feels “so sorry” and he has “lost his brothers” in last Wednesday’s brutal attack on the French satirical magazine’s offices, where 12 people — including cartoonists Stéphane Charbonnier aka Charb, Jean Cabut aka Cabu, Georges Wolinski and Bernard Verlhac aka Tignous — were killed.

Kart also ran into trouble with Turkish authorities back in 2005, when he was fined 5,000 Turkish lira for drawing then-Prime Minister Erdogan as a cat entangled in yarn. Kart puts the spotlight on Erdogan’s chequered history with cartoonists rights in a second piece, where the president declares that: “I condemn the attack. Ten years prison would have been enough for the cartoonists.”

TV: “Massacre in Paris. Twelve dead.” President Erdogan: “I condemn the attack. 10 years prison would have been enough for the cartoonists.”

Erdogan condemned the “heinous terrorist attack” and Turkey’s Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu joined last Sunday’s march for unity in Paris. Much has been made of the apparent hypocrisy of world leaders who have suppressed free speech at home, taking part in what many considered a defiant show of support for that very right.

As Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg pointed out, Turkey imprisons more journalists than any other country in the world. Index’s media freedom map has received 72 reports of press freedom violations from Turkey since May 2014 alone. In the wake of the attacks in Paris, other Turkish cartoonists have been threatened by pro-government social media users. Police also raided the printing press of Cumhuriyet, as it prepared to publish selections from today’s issue of Charlie Hebdo.

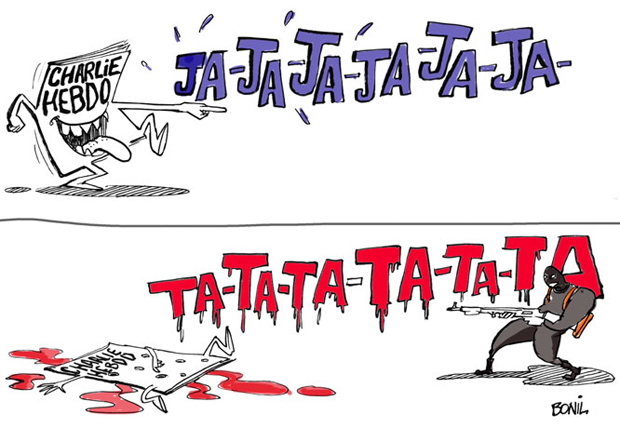

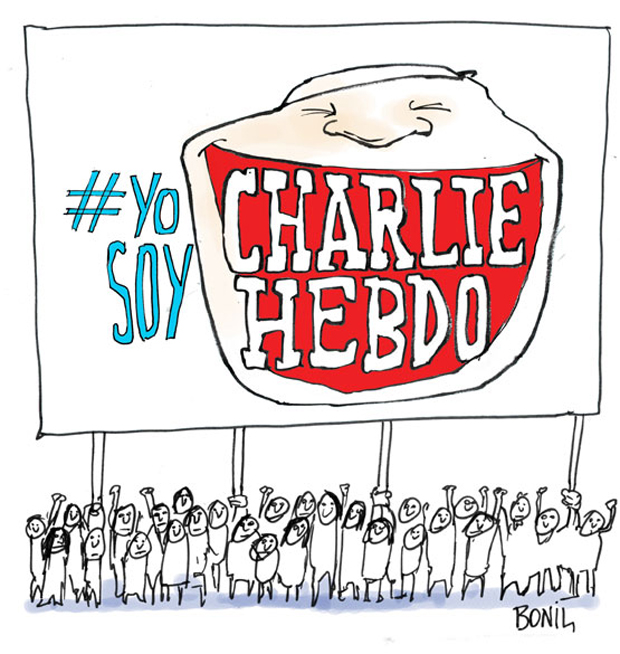

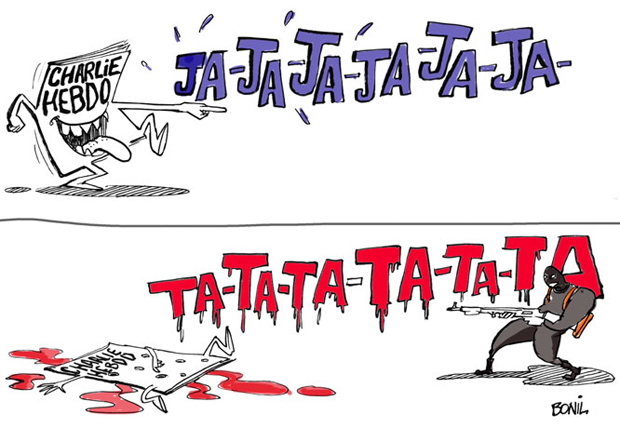

Ecuadorian cartoonist Xavier Bonilla — known as Bonil — has also been targeted for his work. In 2013, the country got a new communications law which allows the government to fine and prosecute the media. After drawing a cartoon for El Universo, based on a raid on the home of a journalist and opposition advisor, Bonil became a victim of the new legislation. President Rafael Correa — who has been known to personally file lawsuits against critical journalists — ordered that a case be opened against the cartoonist. It found that his piece had invited social unrest and should be “rectified”, while El Universo was fined $92,000.

“I believe that humour is the best antidote to fear and the best defence against abuses of power. I have been drawing for 30 years, and I am not going to back down,” he wrote in an article in the current issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

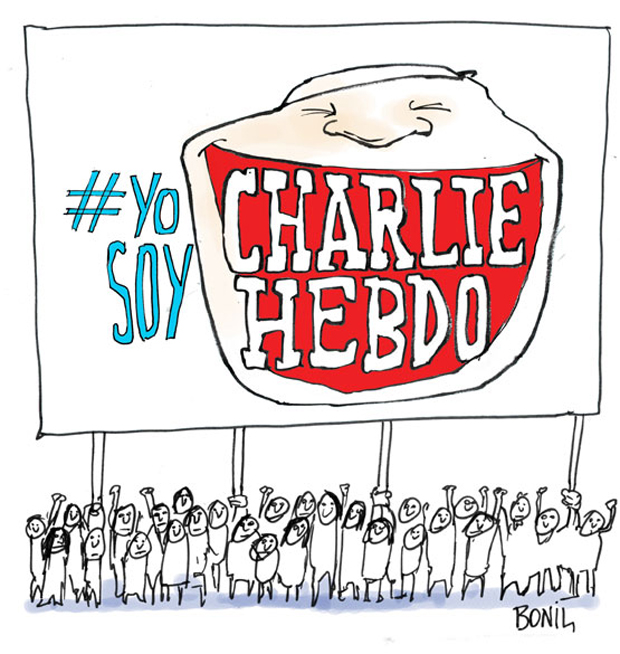

Below are his cartoons in support of Charlie Hebdo.

Cartoon courtesy of Bonil

“New ‘religion’: extremism”

#IAmCharlieHebdo

This article was posted on 14 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org