10 Jan 2014 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

The EU has made a number of positive contributions to digital freedom: it plays a positive part in the global debate on internet governance; the EU’s No-Disconnect Strategy, its freedom of expression guidelines and its export controls on surveillance equipment have all be useful contributions to the digital freedom debate, offering practical measures to better protect freedom of expression. Comparatively, some of the EU’s member states are amongst the world’s best for protecting online freedom. The World Wide Web Foundation places Sweden at the top of its 2012 Index of internet growth, utility and impact, with the UK, Finland, Norway and Ireland also in the top 10. Freedom House ranks all EU member states as “free”, and an EU member state, Estonia, ranks number one globally in the organisation’s annual survey, “Freedom in the World”. But these indices merely represent a snapshot of the situation and even those states ranked as free fail to fully uphold their freedom of expression obligations, online as well as offline.

As the recent revelations by whistleblower Edward Snowden have exposed, although EU member states may in public be committed to a free and open internet, in secret, national governments have been involved in a significant amount of surveillance that breaches international human rights norms, as well as these governments’ own legal commitments. It is also the case that across the EU, other issues continue to chill freedom of expression, including the removal or takedown of legitimate content.

The EU’s position on digital freedom is analysed in more detail in Index on Censorship’s policy paper “Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?” The paper points out that the EU still lacks a coherent overarching strategy and set of principles for promoting and defending freedom of expression in the digital sphere.

Surveillance

Recent revelations by former US National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower Edward Snowden into the NSA’s PRISM programme have also exposed that mass state surveillance by EU governments is practised within the EU, including in the UK and France.

Mass or blanket surveillance contravenes Article 8 (the right to respect for private and family life) and Article 10 (the right to freedom of expression) of the European Convention on Human Rights. In its jurisprudence, the European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly stated that surveillance, if conducted without adequate judicial oversight and with no effective safeguards against abuse, will never be compatible with the European Convention.[1]

This state surveillance also breaches pledges EU member states have made as part of the EU’s new cybersecurity strategy, which was agreed in February 2013 and addresses mass state surveillance. The Commission stated that cybersecurity is predominantly the responsibility of member states, an approach some have argued gives member states the green light for increased government surveillance. Because the strategy explicitly states that “increased global connectivity should not be accompanied by censorship or mass surveillance”, member states were called upon to address their adherence to this principle at the European Council meeting on 24th October 2013. The Council was asked to address revelations that external government surveillance efforts, such as the US National Security Agency’s Prism programme, undermining EU citizens’ rights to privacy and free expression. While the Council did discuss surveillance, as yet there has been no common EU position on these issues.

At the same time, the EU has also played a role in laying the foundations for increased surveillance of EU citizens. In 2002, the EU e-Privacy Directive introduced the possibility for member states to pass laws mandating the retention of communications data for security purposes. In 2006, the EU amended the e-Privacy Directive by enacting the Data Retention Directive (Directive 2006/24/EC), which obliges member states to require communications providers to retain communications data for a period of between six months and two years, which could result in member states collecting a pool of data without specifying the reasons for such practice. A number of individual member states, including Germany, Romania and the Czech Republic, have consulted the European Convention on Human Rights and their constitutions and have found that the mass retention of individual data through the Data Retention Directive to be illegal.

While some EU member states are accused of colluding in mass population surveillance, others have some of the strongest protections anywhere globally to protect their citizens against surveillance. Two EU member states, Luxembourg and the Czech Republic, require that individuals who are placed under secret surveillance to be notified. Other EU member states have expanded their use of state surveillance, in particular Austria, the UK and Bulgaria. Citizens of Poland are subject to more phone tapping and surveillance than any other citizens in the European Union; the European Commission has claimed the police and secret services accessed as many as 1,300,000 phone bills in 2010 without any oversight either by the courts or the public prosecutor.

Internet governance

At a global level the EU has argued for no top-down state control of internet governance. There are efforts by a number of states including Russia, China and Iran to increase state control of the internet through the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). The debate on global internet governance came to a head at the Dubai World Conference on International Telecommunications (WCIT) summit at the end of 2012 which brought together 193 member states. At the WCIT, a number of influential emerging democratic powers aligned with a top-down approach with increased state intervention in the governance of the internet. On the other side, EU member states, India and the US argued the internet should remain governed by an open and collaborative multistakeholder approach. The EU’s influence could be seen through the common position adopted by the member states. The European Commission as a non-voting WCIT observer produced a common position for member states that opposed any new treaty on internet governance under the UN’s auspices. The position ruled out any attempts to make the ITU recommendations binding and would only back technology neutral proposals – but made no mention of free expression. The absence of this right is of concern as other rights including privacy (which was mentioned) do not always align with free speech. After negotiations behind closed doors, all 27 EU member states and another 28 countries including the US abstained from signing the final treaty. That states with significant populations and rising influence in their regions did not back the EU and leant towards more top-down control of the internet should be of significant concern for the EU.

Intermediate liability, takedown and filtering

European laws on intermediate liability, takedown and filtering are overly vague in defining what constitutes valid and legitimate takedown requests, which can lead to legal uncertainty for both web operators and users. Removal of content without a court order can be problematic as it places the content host in the position of judge and jury over content and inevitably leads to censorship of free expression by private actors. EU directorate DG MARKT[2] is currently looking into the results of a public consultation into how takedown requests affect freedom of expression, among other issues. It is expected that the directorate will outline a directive or communication on the criteria takedown requests must meet and the evidence threshold required, while also clarifying how “expeditiously” intermediaries must act to avoid liability. A policy that clarifies companies’ legal responsibilities when presented with takedown requests should help better protect online content from takedown where there is no legal basis for the complaint.

The EU must take steps to protect web operators from vexatious claims from individuals over content that is not illegal. Across the EU, the governments of member states are increasingly using takedown requests. Google has seen a doubling of requests from the governments of Germany, Hungary, Poland and Portugal from 2010-2012; a 45% increase from Belgium and double-digit growth in the Netherlands, Spain and the UK. Governments are taking content down for dubious reasons that may infringe Article 10 rights of the ECHR. In 2010, a number of takedown requests were made in response to ‘”government criticism” and four in response to “religious offence”. A significant 8% of takedown requests were in response to defamation offences. With regard to defamation charges, it must be noted that the public interest is not protected equally across all EU countries (see Defamation above).

Although corporate takedown is more prevalent than state takedown, particularly in the number of individual URLs affected, the outcome of the DG MARKT consultation must be to address both vexatious state and corporate takedown requests. The new communication or directive must be clearer than the EU e-Commerce directive has been with respect to the responsibility of member states. While creating a legal framework that was intended to protect internet intermediaries, the EU e-Commerce directive has failed to be entirely effective in a number of high-profile cases. EU member states use filters to prevent the distribution of child pornography with questionable effectiveness. However, filters have not been used by states to block other content after a Court of Justice of the European Union ruling stated EU law did not allow states to require internet service providers to install filtering systems to prevent the illegal distribution of content. The Court made it clear at the time that such filtering would require ISPs to monitor internet traffic, an infringement under EU law. This has granted European citizens strong protections against systematic web filtering on behalf of states. There continue to be legal attempts to force internet intermediaries to block content that is already in the public domain. In a recent case, brought by the Spanish Data Protection authority on behalf of a complainant, the authority demanded that the search engine Google remove results that pointed to an auction note for a reposessed home due to social security debts. The claimant insisted that referring to his past debts infringed on his right to privacy and asked for the search results to be removed. In June 2013, the Advocate General of the European Court of Justice decided Google did not need to comply to the request to block “legal and legitimate information that has entered the public domain” and that it is not required to remove information posted by third parties. Google has estimated that there are 180 cases similar to this one in Spain alone. A final decision in the case is expected before the end of this year, which could have profound implications for intermediate liability.

[1] In Liberty v. UK (58243/00) the ECHR stated: “95. In its case-law on secret measures of surveillance, the Court has developed the following minimum safeguards that should be set out in statute law in order to avoid abuses of power: the nature of the offences which may give rise to an interception order; a definition of the categories of people liable to have their telephones tapped; a limit on the duration of telephone tapping; the procedure to be followed for examining, using and storing the data obtained; the precautions to be taken when communicating the data to other parties; and the circumstances in which recordings may or must be erased or the tapes destroyed”; A. v. France (application no. 14838/89), 23.11.1993: found a violation of Article 8 after a recording was carried out without following a judicial procedure and which had not been ordered by an investigating judge; Drakšas v. Lithuania, 31.07.2012, found a violation of Article 13 (right to an effective remedy) on account of the absence of a judicial review of the applicant’s surveillance after 17 September 2003.

[2] The Internal Market and Services Directorate General

9 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

Sokratis Giolia, an investigative journalist, was shot dead outside his home in Athens prior to publishing the results of an investigation into corruption.

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

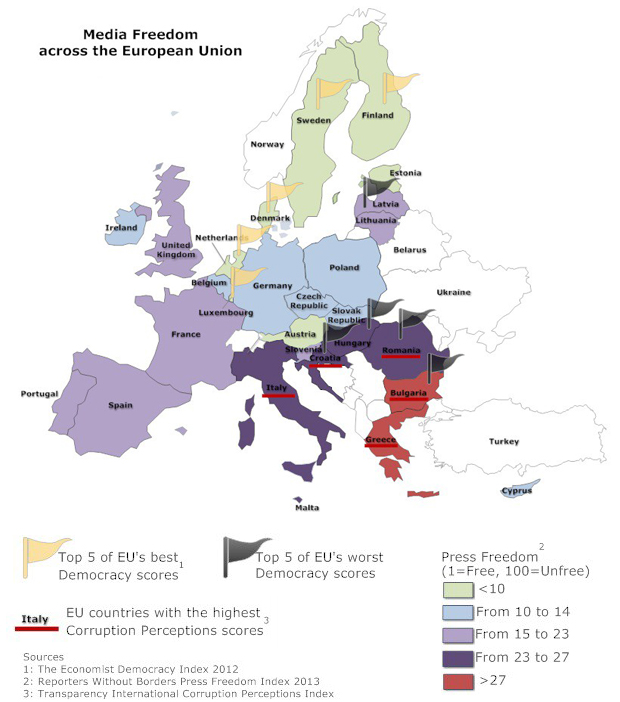

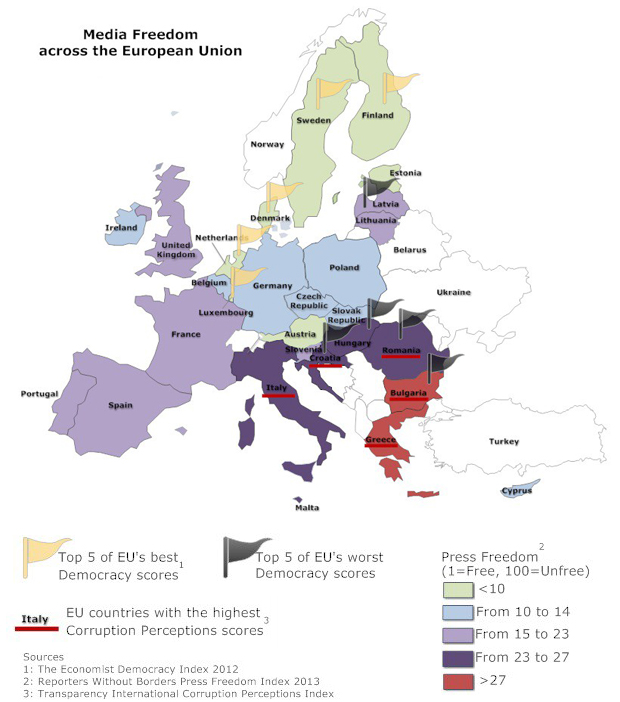

The main threats to media freedom and the work of journalists are from political pressure or pressure exerted by the police, to non-legal means, such as violence and impunity. There have been instances where political pressure against journalists has led to self-censorship in a number of European Union countries. This pressure can manifest itself in a number of ways, from political pressure to influence editorial decisions or block journalists from promotion in state broadcasters to police or security service interventions into media investigations on political corruption.

The European Commission now has a clear competency to protect media freedom and should reflect on how it can deal with political interference in the national media of member states. As the heads of state or government of the EU member states have wider decision-making powers at the European Council this gives a forum for influence and negotiation, but this may also act as a brake on Commission action, thereby protecting media freedom.

Italy presents perhaps the most egregious example of political interference undermining media freedom in a EU member state. Former premier Silvio Berlusconi has used his influence over the media to secure personal political gain on a number of occasions. In 2009 he was thought to be behind RAI decision to stop broadcasting Annozero, a political programme that regularly criticised the government. In the lead up to the 2010 regional elections, Berlusconi’s party pushed through rules which effectively meant that state broadcasters had to either feature over 30 political parties on their talk shows or lose their prime time slots. Notably, Italian state broadcaster RAI refused to show adverts for the Swedish film Videocracy because it claimed the adverts were “offensive” to Silvio Berlusconi.

Under the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Hungary has seen considerable political interference in the media. In September 2011, popular liberal political radio station “Klubrádió” lost its licence following a decision by the Media Authority that experts believed was motivated by political considerations. The licence was reinstated on appeal. In December 2011, state TV journalists went on hunger strike after the face of a prominent Supreme Court judge was airbrushed out of a broadcast by state-run TV channel MTV. Journalists have complained that editors regularly cave into political interference. Germany has also seen instances of political interference in the public and private media. In 2009, the chief editor of German public service broadcaster ZDF, Nikolaus Brender, saw his contract terminated in controversial circumstances. Despite being a well-respected and experienced journalist, Brender’s suitability for the job was questioned by politicians on the channel’s executive board, many of whom represented the ruling Christian Democratic Union. It was decided his contract should not be renewed, a move widely criticised by domestic media, the International Press Institute and Reporters Without Borders, the latter arguing the move was “motivated by party politics” which, it argued, was “a blatant violation of the principle of independence of public broadcasters”. In 2011, the editor of Germany’s (and Europe’s) biggest selling newspaper, Bild, received a voicemail from President Christian Wulff, who threatened “war” on the tabloid if it reported on an unusual personal loan he received.

Police interference in the work of journalists, bloggers and media workers is a concern: there is evidence of police interference across a number of countries, including France, Ireland and Bulgaria. In France, the security services engaged in illegal activity when they spied on Le Monde journalist Gerard Davet during his investigation into Liliane Bettencourt’s alleged illegal financing of President Sarkozy’s political party. In 2011, France’s head of domestic intelligence, Bernard Squarcini, was charged with “illegally collecting data and violating the confidentiality” of the journalists’ sources. In Bulgaria, journalist Boris Mitov was summoned on two occasions to the Sofia City Prosecutor’s office in April 2013 for leaking “state secrets” after he reported a potential conflict of interest within the prosecution team. Of particular concern is Ireland, which has legislation that outlaws contact between ordinary police officers and the media. Clause 62 of the 2005 Garda Siochána Act makes provision for police officers who speak to journalists without authorisation from senior officers to be dismissed, fined up to €75,000 or even face seven years in prison. This law has the potential to criminalise public interest police whistleblowing.[1]

It is worth noting that after whistleblower Edward Snowden attempted to claim asylum in a number of European countries, including Austria, Finland, Germany, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, the governments of all of these countries stated that he needed to be present in the country to claim asylum. Others went further. Poland’s Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski posted the following statement on Twitter: “I will not give a positive recommendation”, while German Foreign minister Guido Westerwelle said although Germany would review the asylum request “according to the law”, he “could not imagine” that it would be approved. The failure of the EU’s member states to give shelter to Snowden when so much of his work was clearly in the public interest within the European Union shows the scale of the weakness within Europe to stand up for freedom of expression.

Deaths, threats and violence against journalists and media workers

No EU country features in Reporters Without Borders’ 2013 list of deadliest countries for journalists. But since 2010, three journalists have been killed within the European Union. In Bulgaria in January 2010 , a gunman shot and killed Boris Nikolov Tsankov, a journalist who reported on the local mafia, as he walked down a crowded street. The gunman escaped on foot. In Greece, Sokratis Giolia, an investigative journalist, was shot dead outside his home in Athens prior to publishing the results of an investigation into corruption. In Latvia, media owner Grigorijs Nemcovs was the victim of an apparent contract killing, which Reporters Without Borders claims appeared to be carefully planned and executed.103 Nemcovs was also a political activist and deputy mayor, and his newspaper, Million, was renowned for its investigative coverage of political and local government corruption and mismanagement.

While it is rare for journalists to be killed within the EU, the Council of Europe has drawn attention to the fact that violence against journalists does occur in EU countries, particularly in south eastern Europe, including in Greece, Latvia, Bulgaria and Romania.[2] The South East Europe Media Organisation (SEEMO) has raised concerns over police violence against journalists covering political protests in many parts of south eastern Europe, particularly in Romania and Greece.

[1] There is an official whistleblowing mechanism instituted by the law, but it is not independent of the police.

[2] William Horsley for rapporteur Mats Johansson, ‘The State of Media Freedom in Europe’, Committee on Culture, Science, Education and Media, Council of Europe (18 June 2012).

2 Jan 2014 | European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

The law of libel, privacy and national “insult” laws vary across the European Union. In a number of member states, criminal sanctions are still in place and public interest defences are inadequate, curtailing freedom of expression.

The European Union has limited competencies in this area, except in the field of data protection, where it is devising new regulations. Due to the impact on freedom of expression and the functioning of the internal market, the European Commisssion High Level Group on Media Freedom and Pluralism recommended that libel laws be harmonised across the European Union. It remains the case that the European Court of Human Rights is instrumental in defending freedom of expression where the laws of member states fail to do so. Far too often, archaic national laws have been left unreformed and therefore contain provisions that have the potential to chill freedom of expression.

Nearly all EU member states still have not repealed criminal sanctions for defamation – with only Croatia,[1] Cyprus, Ireland, Romania and the UK[2] having done so. The parliamentary assembly of the Council of Europe called on states to repeal criminal sanctions for libel in 2007, as did both the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and UN special rapporteurs on freedom of expression.[3] Criminal defamation laws chill free speech by making it possible for journalists to face jail or a criminal record (which will have a direct impact on their future careers), in connection with their work. Many EU member states have tougher sanctions for criminal libel against politicians than ordinary citizens, even though the European Court of Human Rights ruled in Lingens v. Austria (1986) that:

“The limits of acceptable criticism are accordingly wider as regards a politician as such than as regards a private individual.”

Of particular concern is the fact that insult laws remain in place in many EU member states and are enforced – particularly in Poland, Spain, and Greece – even though convictions are regularly overturned by the European Court of Human Rights. Insult to national symbols is also criminalised in Austria, Germany and Poland. Austria has the EU’s strictest laws in this regard, with the penal code criminalising the disparagement of the state and its symbols[4] if malicious insult is perceived by a broad section of the republic. This section of the code also covers the flag and the federal anthem of the state. In November 2013, Spain’s parliament passed draft legislation permitting fines of up to €30,000 for “insulting” the country’s flag. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muiznieks, criticised the proposals stating they were of “serious concern”.

There is a wide variance in the application of civil defamation laws across the EU – with significant differences in defences, costs and damages. Excessive costs and damages in civil defamation and privacy actions is known to chill free expression, as authors fear ruinous litigation, as recognised by the European Court of Human Rights in MGM vs UK.[5] In 2008, Oxford University found huge variants in the costs of defamation actions across the EU, from around €600 (constituting both claimants’ and defendants’ costs) in Cyprus and Bulgaria to in excess of €1,000,000 in Ireland and the UK. Defences for defendants vary widely too: truth as a defence is commonplace across the EU but a stand-alone public interest defence is more limited.

Italy and Germany’s codes provide for responsible journalism defences instead of using a general public interest defence. In contrast, the UK recently introduced a public interest defence that covers journalists, as well as all organisations or individuals that undertake public interest publications, including academics, NGOs, consumer protection groups and bloggers. The burden of proof is primarily on the claimant in many European jurisdictions including Germany, Italy and France, whereas in the UK and Ireland, the burden is more significantly on the defendant, who is required to prove they have not libelled the claimant.

Privacy

Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights protects the right to a private life throughout the European Union. [6] The right to freedom of expression and the right to a private right are often complementary rights, in particular in the online sphere. Privacy law is, on the whole, left to EU member states to decide. In a number of EU member states, the right to privacy can restrict the right to freedom of expression because there are limited protections for those who breach the right to privacy for reasons of public interest.

The media’s willingness to report and comment on aspects of people’s private lives, in particular where there is a legitimate public interest, has raised questions over the boundaries of what is public and what is private. In many EU member states, the media’s right to freedom of expression has been overly compromised by the lack of a serious public interest defence in privacy law. This is most clearly illustrated by the fact that some European Union member states offer protection for the private lives of politicians and the powerful, even when publication is in the public interest, in particular in France, Italy and Germany. In Italy, former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi used the country’s privacy laws to successfully sue the publisher of Italian magazine Oggi for breach of privacy after the magazine published photographs of the premier at parties where escort girls were allegedly in attendance. Publisher Pino Belleri received a suspended five-month sentence and a €10,000 fine. The set of photographs proved that the premier had used Italian state aircraft for his own private purposes, in breach of the law. Even though there was a clear public interest, the Italian Public Prosecutor’s Office brought charges. In Slovakia, courts also have a narrow interpretation of the public interest defence with regard to privacy. In February 2012, a District Court in Bratislava prohibited the distribution or publication of a book alleging corrupt links between Slovak politicians and the Penta financial group. One of the partners at Penta filed for a preliminary injunction to ban the publication for breach of privacy. It took three months for the decision to be overruled by a higher court and for the book to be published.

The European Court of Human Rights rejected former Federation Internationale de l’Automobile president Max Mosley’s attempt to force newspapers to give prior notification in instances where they may breach an individual’s right to a private life, noting that the requirement for prior notification would likely chill political and public interest matters. Yet prior notification and/or consent is currently a requirement in three EU member states: Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Other countries have clear public interest defences. The Swedish Personal Data Act (PDA), or personuppgiftslagen (PUL), was enacted in 1998 and provides strong protections for freedom of expression by stating that in cases where there is a conflict between personal data privacy and freedom of the press or freedom of expression, the latter will prevail. The Supreme Court of Sweden backed this principle in 2001 in a case where a website was sued for breach of privacy after it highlighted criticisms of Swedish bank officials.

When it comes to data retention, the European Union demonstrates clear competency. As noted in Index’s policy paper “Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?“, published in June 2013, the EU is currently debating data protection reforms that would strengthen existing privacy principles set out in 1995, as well as harmonise individual member states’ laws. The proposed EU General Data Protection Regulation, currently being debated by the European Parliament, aims to give users greater control of their personal data and hold companies more accountable when they access data. But the “right to be forgotten” clause of the proposed regulation has been the subject of controversy as it would allow internet users to remove content posted to social networks in the past. This limited right is not expected to require search engines to stop linking to articles, nor would it require news outlets to remove articles users found offensive from their sites. The Center for Democracy and Technology referred to the impact of these proposals as placing “unreasonable burdens” that could chill expression by leading to fewer online platforms for unrestricted speech. These concerns, among others, should be taken into consideration at the EU level. In the data protection debate, freedom of expression should not be compromised to enact stricter privacy policies.

This article was posted on Jan 2 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

[1] Article 208 of the Criminal Code.

[2] Article 168(2) of the Criminal Code.

[3] Article 248 of the Criminal Code prohibits ‘disparagement of the State and its symbols, ibid, International PEN.

[4] Index on Censorship, ‘UK government abolishes seditious libel and criminal defamation’ (13 July 2009)

[5] More recent jurisprudence includes: Lopes Gomes da Silva v Portugal (2000); Oberschlick v Austria (no 2) (1997) and Schwabe v Austria (1992) which all cover the limits for legitimate criticism of politicians.

[6] Privacy is also protected by the Charter of Fundamental Rights through Article 7 (‘Respect for private and family life’) and Article 8 (‘Protection of personal data’).

27 Dec 2013 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression.

Since the entering into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, which made the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights legally binding, the EU has gained an important tool to deal with breaches of fundamental rights.

The Lisbon Treaty also laid the foundation for the EU as a whole to accede to the European Convention on Human Rights. Amendments to the Treaty on European Union (TEU) introduced by the Lisbon Treaty (Article 7) gave new powers to the EU to deal with state who breach fundamental rights.

The EU’s accession to the ECHR, which is likely to take place prior to the European elections in June 2014, will help reinforce the power of the ECHR within the EU and in its external policy. Commission lawyers believe that the Lisbon Treaty has made little impact, as the Commission has always been required to assess whether legislation is compatible with the ECHR (through impact assessments and the fundamental rights checklist) and because all EU member states are also signatories to the Convention.[1] Yet external legal experts believe that accession could have a real and significant impact on human rights and freedom of expression internally within the EU as the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) will be able to rule on cases and apply European Court of Human Rights jurisprudence directly. Currently, CJEU cases take approximately one year to process, whereas cases submitted to the ECHR can take up to 12 years. Therefore, it is likely that a larger number of freedom of expression cases will be heard and resolved more quickly at the CJEU, with a potential positive impact on justice and the implementation of rights in the EU.[2]

The Commission will also build upon Council of Europe standards when drafting laws and agreements that apply to the 28 member states. Now that these rights are legally binding and are subject to formal assessment, this may serve to strengthen rights within the Union.[3] For the first time, a Commissioner assumes responsibility for the promotion of fundamental rights; all members of the European Commission must pledge before the Court of Justice of the European Union that they will uphold the Charter.

The Lisbon Treaty also provides for a mechanism that allows European Union institutions to take action, whether there is a clear risk of a “serious breach” or a “serious and persistent breach”, by a member state in their respect for human rights in Article 7 of the Treaty of the European Union. This is an important step forward, which allows for the suspension of voting rights of any government representative found to be in breach of Article 7 at the Council of the European Union. The mechanism is described as a “last resort”, but does potentially provide leverage where states fail to uphold their duty to protect freedom of expression.

Yet within the EU, some remained concerned that the use of Article 7 of the Treaty, while a step forward, is limited in its effectiveness because it is only used as a last resort. Among those who argued this were Commissioner Reding, who called the mechanism the “nuclear option” during a speech addressing the “Copenhagen Dilemma” (the problem of holding states to the human rights commitments they make when they join). In March 2013, in a joint letter sent to Commission President Barroso, the foreign ministers of the Netherlands, Finland, Denmark and Germany called for the creation of a mechanism to safeguard principles such as democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The letter argued there should be an option to cut EU funding for countries that breach their human rights commitments.

It is clear that there is a fair amount of thinking going on internally within the Commission on what to do when member states fail to abide by “European values”. Commission President Barroso raised this in his State of the Union address in September 2012, explicitly calling for “a better developed set of instruments” to deal with threats to these rights.

This thinking has been triggered by recent events in Hungary and Italy, as well as the ongoing issue of corruption in Bulgaria and Romania, which points to a wider problem the EU faces through enlargement: new countries may easily fall short of both their European and international commitments.

Full report PDF: Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Footnotes

[1] Off-record interview with a European Commission lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).

[2] Interview with Prof. Andrea Biondi, King’s College London, 22 April 2013.

[3] Interview with lawyer, Brussels (February 2013).