Journalists’ safety key focus for World Press Freedom Day conference

Journalists from around the world are marking UNESCO’s 20th annual World Press Freedom Day in San Jose, Costa Rica.

Driven by the deaths of 600 journalists over the past decade, this year’s conference — a series of panels, workgroups and ceremonies — is devoted to the theme of promoting safety and ending impunity for journalists, bloggers and everyday citizens who cross red lines to speak their minds. The gathering also honours journalists who have been attacked, imprisoned or died for their work. Of the 600 killed, only in 10 percent of cases have those responsible been punished.

This year’s theme is on promoting safety and ending impunity for journalists, bloggers, media workers and everyday citizens who cross red lines to speak their minds. The annual 3 May conference is a series UNESCO hosts a series of panels, workshops and ceremonies to evaluate global press freedom and to honour journalists who have been attacked, imprisoned or died for their work.

Journalists gathered in Costa Rica to mark World Press Freedom Day. Photo: Brian Pellot / Index on Censorship

Most of the first day’s sessions provided analysis of the dangers journalists face.

In societies where journalists feel unsafe or where attacks against them go unpunished, a culture of self censorship often emerges. Javier Darío Restrepo, a journalist and writer from Colombia, said journalists self censor to survive, but in doing so they cease to be a voice of the powerless in their societies. Building on that point, OSCE’s representative on freedom of the media Dunja Mijatović described the right of journalists to carry out their work without fear — an important prerequisite for media freedom in society.

One common reference on day one of the conference was the recently published UN Plan of Action on Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity – which Index on Censorship contributed to. The plan calls on UN agencies, member states, NGOs and media organisations to work together in promoting the safety of journalists and raising awareness of the primary threats they face.

Adnan Rehmat, executive director at Intermedia Pakistan, said the main issues facing press freedom in his country are that attacks on journalists are not recognised as attacks on freedom of expression. One positive development he mentioned was the establishment of a Pakistan Journalist Safety Fund to provide assistance for journalists in distress.

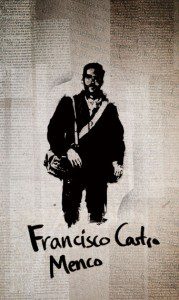

In the same discussion, Andrés Morales, executive director of La Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa in Colombia, cited a recent attack on noted Colombian investigative journalist Ricardo Calderon as indicative of the wider problems facing journalists in the region and around the world. Colombia has seen a markeddecline in the number of journalists murdered in the past decade, which he attributes in part to a protection programme for journalists but also to self censorship. Many journalists believe that if they don’t write about sensitive issues, they won’t be punished for their words.

In a panel devoted specifically to freedom of expression in Costa Rica, local journalist Mauricio Herrera Ullola outlined some of the greatest obstacles media professionals face in his country today. By some measures, Costa Rica’s press can be considered free. But “crimes against honour” are still prosecuted criminally and carry a penalty of up to 100 days in prison if someone feels personally insulted by a journalist’s story. Herrera Ullola said that media ownership is very concentrated, self-censorship is common, and current laws around slander and libel can be chilling in Costa Rica. He also said the country needs freedom of information laws to promote greater transparency and access to public records.

Several speakers described great improvements for the rights of women, indigenous populations, youth and sexual minorities across Latin America in recent decades, but agreed that many countries in the region still have work to do to ensure full freedom of expression. Colombia and Mexico are both on the Committee to Protect Journalists’ top 10 list of deadliest countries for journalists, a clear sign that freedom of expression remains under attack in the region.

In a poignant moment during the conference’s first day, one delegate asked whether journalists dying on the job is an occupational hazard; an unavoidable price society must pay for good journalism and ultimately for the truth. Adnan Rehmat from Intermedia Pakistan responded: “The price of journalism should not be more than feeling tired after a long day’s work.”

Brian Pellot is Index on Censorship’s Digital Policy Adviser. UNESCO’s three days of events for World Press Freedom Day in Costa Rica complement dozens of local and regional events around the world. Follow Brian on Twitter @brianpellot (along with the hashtags #wpfd and #pressfreedom) as he reports on the rest of the conference, and read the full programme of events in Costa Rica here.

World Press Freedom Day

European Union: Is the European Union faltering on media freedom?

Tunisia: Press faces repressive laws, uncertain future

Egypt: Post-revolution media vibrant but partisan

Brazil: Press confronts old foes and new violence

Index joins civil society groups in voicing concerns about proposals made by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) that would threaten the openness of the internet

Index joins civil society groups in voicing concerns about proposals made by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) that would threaten the openness of the internet