Spring 2015: Across the wires – how refugee stories get told

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”How can more refugees get their voices heard? The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine is out now and features a special focus on the threats to free expression within refugee camps.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

We follow the steps of Italian journalist Fabrizio Gatti, who spent four years undercover investigating migrant routes from Africa to Europe. We look at how social media has become a blessing and a curse – offering a connection back home and a means of surveillance. We have pieces by refugees, written from inside camps about persisting myths; by those struggling to claim rights as workers; and by those who have set up innovative, creative projects to share their stories.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_single_image image=”64776″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

The issue also features a thoughtful analysis of the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris, with contributions from Chilean writer Ariel Dorfman; Irish co-creator of Father Ted, Arthur Mathews; Turkish novelist Elif Shafak; British playwright David Edgar; former head of BBC news Richard Sambrook; and Hong Kong-based journalist Hannah Leung. Taking the long view, this group of writers looks at the worldwide picture, and how terror is used to silence.

Also, Martha Lane Fox and retired Major General Tim Cross go head-to-head, debating if privacy is more vital than national security. We have stories about attacks on journalists covering the drug trade in South America; a cover-up of abortion figures in Nicaragua; and the lessons to be learnt from attempts to downplay epidemics, from Aids to ebola. Plus an extract from Lucien Bourjeily’s new play, which has skirted the Lebanese censors’ ban, and poetry from Turkish writers Ömer Erdem and Nilay Özer – all translated into English for the first time.

The issue’s cover artwork is by cartoonist Ben Jennings, and the magazine also features work from our regular collaborator Martin Rowson; and extracts from a graphic reportage set in an Iraqi camp, by Olivier Kugler.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: ACROSS THE WIRES” css=”.vc_custom_1483457468599{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

How refugee stories get told

Undercover immigrant – Italian journalist Fabrizio Gatti spent four years undercover investigating refugee routes from Africa to Europe

Taking control of the camera – Almir Koldzic and Aine O’Brien on refugee camp projects – from soap operas to photography classes – that help refugees tell their own stories. Also: Valentino Achak Deng on life after fleeing Sudan’s civil war; Kate Maltby visits the Syrian Trojan Women’s acting project; and Preti Taneja on bringing Shakespeare to the children of Zaatari

The way I see it – Refugees Rana Moneim and Mohammed Maarouf share their viewpoints from inside a camp, plus a camp visitor shatters his preconceptions

Clear connections – Jason DaPonte on how social media’s power is being harnessed by refugees

Who tells the stories? – Mary Mitchell and Mohammed Al Assad on a storytelling project in a Lebanon camp

Realities of the promised land – Iara Beekma looks at life for Haitian immigrants in Brazil and their rights as workers

The whole picture – Photojournalist Chris Steele-Perkins’ honest account of decades spent capturing refugees’ stories, from Rwandans to the Rohingha

Stripsearch – Our regular cartoonist, Martin Rowson, imagines the Democratic Republic of Cyberspace

Escape from Eritrea – Ismail Einashe explores the dangers of fleeing one of the world’s harshest regimes

A very human picture – Artist Olivier Kugler illustrates life within Iraq’s Domiz refugee camp

In limbo in world’s oldest refugee camps – Tim Finch looks at the places where 10 million people can spend years, or even decades

Sound and fury – Rachael Jolley interviews musician Martyn Ware, from Heaven 17 and the Human League, on the power of soundscape storytelling

Sheltering against resentment – Natasha Joseph reports from Johannesburg on the end of the line for a sanctuary for those fleeing xenophobia

Understanding how language matters – Kao Kalia Yang recalls her childhood as a Hmong refugee in Thailand and the USA

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Outbreaks under wraps – Alan Maryon-Davis looks at how denials and cover-ups spread ebola, Sars and Aids

Trade secrets – César Muñoz Acebes investigates Paraguay’s drug war and the dangers for journalists, plus Duncan Tucker on Mexico’s courageous bloggers and social media users, who are filling the gaps where Mexico’s press fears to tread

Lies and statistics – Nina Lakhani reports from Nicaragua on the cover-up of abortion figures and domestic abuse

Charlie Hebdo: taking the long view – After the Paris murders, seven writers from around the world look at how offence and terror are used to silence, featuring Arthur Mathews, Ariel Dorfman, David Edgar, Elif Shafak, Hannah Leung, Raymond Louw, Richard Sambrook

Screened shots – Jemimah Steinfeld on the Chinese film industry’s obsession with portraying Japan’s invasion during World War II

Finland of the free – Risto Uimonen explains why the Finns always top media freedom indexes, and the Belfast Telegraph’s readers’ editor, Paul Connolly, shares his thoughts on the future of press regulation

Head to head: Is privacy more vital than national security? Martha Lane Fox and Tim Cross debate how far governments should go when balancing individual rights and safeguarding the nation

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

The state v the poets – Kaya Genç introduces works by Turkish poets Ömer Erdem and Nilay Özer

Knife edge – Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily presents an exclusive extract from his latest play as it escapes the censors’ ban

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

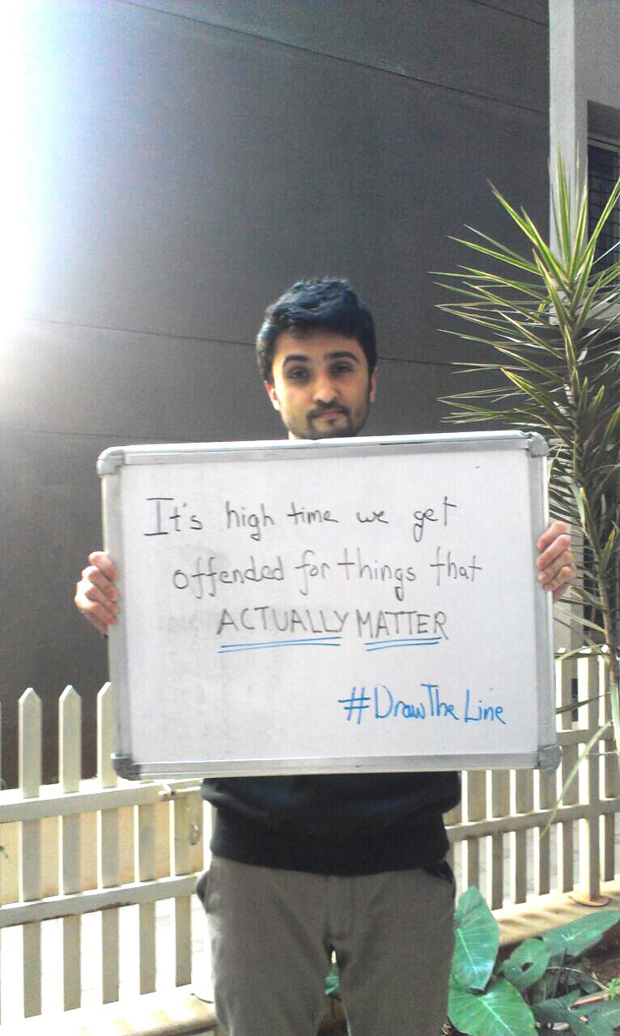

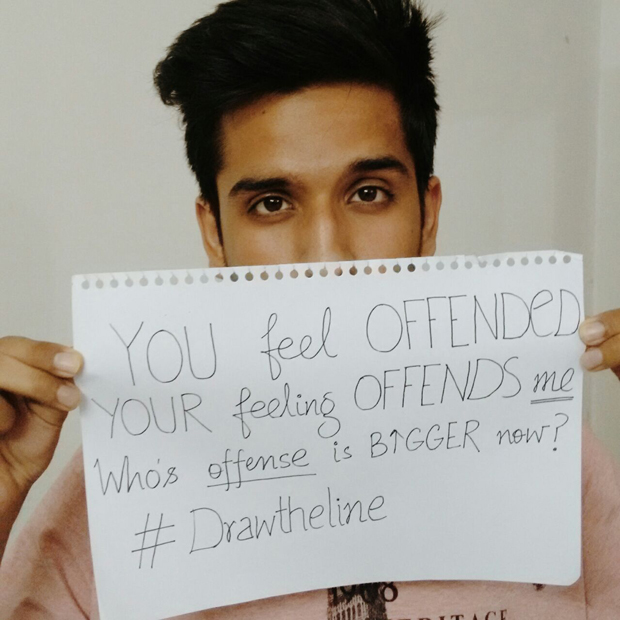

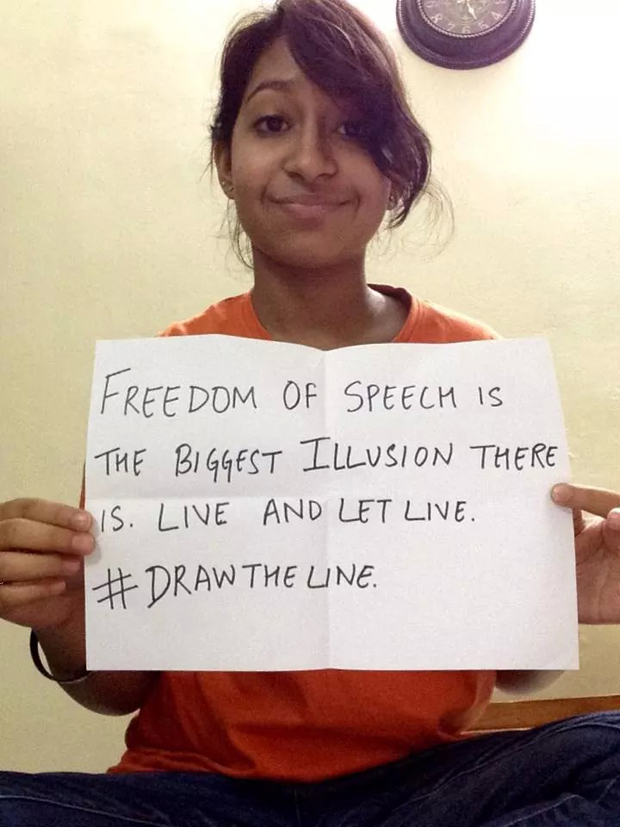

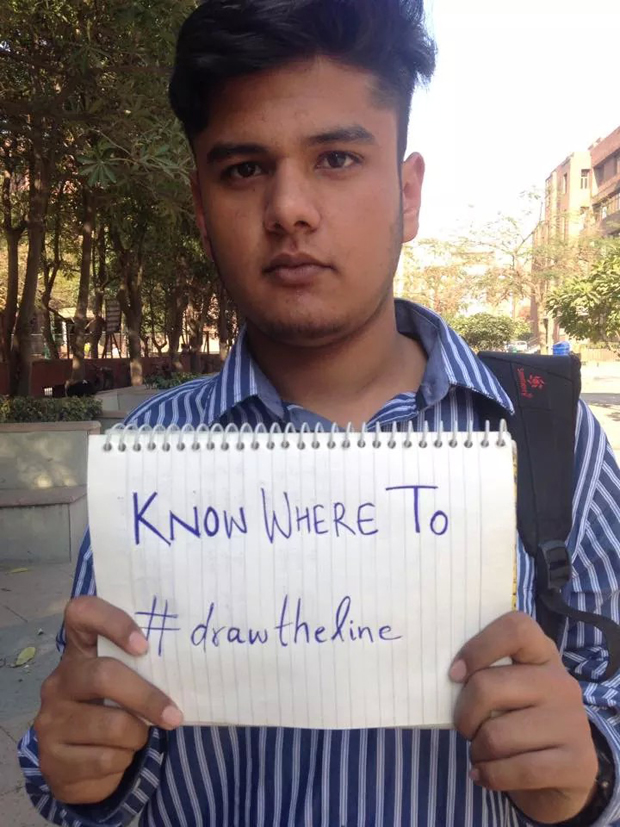

Global view – Index’s CEO Jodie Ginsberg says universities must not fear offence and controversy

Index around the world – Aimée Hamilton provides an update on Index on Censorship’s work

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Social disturbance – Vicky Baker looks at how user-generated content lost its innocence, from digital jihadis to hoaxes and propaganda

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]