3 Oct 2018 | Event Reports, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103062″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]“Critical thinking is important, but we should also be teaching scientific literacy and political literacy so we know what knowledge claims to trust,” said Keith Kahn-Harris, author of Denial: The Unspeakable Truth, at a panel debate during the launch of the autumn 2018 edition of Index on Censorship.

The theme of this quarter’s magazine, The Age of Unreason, looks at censorship in scientific research and whether our emotions are blurring the lines between fact and fiction. From Mexico to Turkey, Hungary to China, a whole range of countries from around the globe were covered for this special report, featuring articles from the likes of Julian Baggini and David Ulin. For the launch, a selection of journalists, authors and academics shared their thoughts on how to have better arguments when emotions are high, while exploring concerns surrounding science and censorship in the current global climate.

Aptly taking place at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, the historical home of scientific research for 14 Nobel Prize winners, Kahn-Harris was joined by BBC Radio 4 presenter Timandra Harkness and New Scientist writer Graham Lawton. The discussion was chaired by Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine.

“Academics and experts are being undermined all over the world,” said Jolley, setting the stage for a riveting conversation between panellists and the audience. “Is this something new or something that has happened throughout history?”

When Jolley asked why science is often the first target of an authoritarian government, Lawton proposed that the value of science is that it is evidence-based and subsequently “kryptonite” to what rigid establishments want to portray. He added: “They depend extremely heavily on telling people half-truths or lies.”[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”103066″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Harkness led a workshop highlighting the importance of applying critical thinking skills when deconstructing arguments, using footage of real-life debates, past and present, to investigate such ideas. Whether it was the first televised contest between presidential candidates John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon in 1960, or a dispute between Indian civilians over LGBT rights earlier this year, a wide variety of topics and discussions were analysed.

Examining a debate between 2016 presidential candidates Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton, Harkness asked an audience member his thoughts. Focusing on Trump’s approach, he said: “He’s put up a totally false premise which is quite a conventional tactic; you put up something that is not what the other person said, and then you proceed to knock it down quite reasonably because it’s unreasonable in the first place.” Harkness agreed. “It’s the straw man tactic”, she said, “where you build something up and then attack it.”

Panellists began discussing how to argue with say those who deny climate change, with Kahn-Harris contending that science has become enormously specialised over the past centuries, which means people cannot always debunk uncertain claims since they are not specialists. He said: “There’s something tremendously smug about the post-enlightenment world.”

Harkness said “robust challenges” should be sought-after rather than silencing those who share different views, while Lawton added that “storytelling and appealing to emotions are perfectly valid ways of arguing.”

For more information on the autumn issue, click here. The issue includes an article on how fact and fiction come together in the age of unreason, why Indian journalism is under threat, Nobel prize-winning novelist Herta Müller on censorship in Romania, and an exclusive short story from bestselling crime writer Ian Rankin. Listen to our podcast here. Or, try our quiz that decides how prone to bullshit you are…[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1538584887174-432e9410-24f0-4″ taxonomies=”8957″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Sep 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish, Spain

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Los periodistas mexicanos son objeto de amenazas por parte de un gobierno corrupto y cárteles violentos, y no siempre pueden confiar en sus compañeros de oficio. Duncan Tucker informa.

“][vc_single_image image=”97006″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]«Espero que el gobierno no se deje llevar por la tentación autoritaria de bloquear el acceso a internet y arrestar activistas», contaba el bloguero y activista mexicano Alberto Escorcia a la revista de Index on Censorship.

Escorcia acababa de recibir una serie de amenazas por un artículo que había escrito sobre el reciente descontento social en el país. Las amenazas se agravaron al día siguiente. Invadido por una sensación de ahogo y desprotección, comenzó a planear su huida del país.

Son muchas las personas preocupadas por el estado de la libertad de expresión en México. Una economía estancada, una moneda en caída libre, una sangrienta guerra antinarco sin final a la vista y un presidente extremadamente impopular, sumados a la administración beligerante de Donald Trump recién instalada en EE.UU. al otro lado de la frontera, llevan todo el año generando cada vez más presión.

Una de las tensiones principales es el propio presidente de México. Los cuatro años que lleva Enrique Peña Nieto en el cargo han traído un parco crecimiento económico. También se está dando un repunte de la violencia y los escándalos por corrupción. En enero de este año, el índice de popularidad del presidente se desplomó hasta el 12%.

Y lo que es peor: los periodistas que han intentado informar sobre el presidente y sus políticas han sufrido duras represalias. 2017 comenzó con agitadas protestas en respuesta al anuncio de Peña Nieto de que habría una subida del 20% a los precios de la gasolina. Días de manifestaciones, barricadas, saqueos y enfrentamientos con la policía dejaron al menos seis muertos y más de 1.500 arrestos. El Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas ha informado que los agentes de policía golpearon, amenazaron o detuvieron temporalmente a un mínimo de 19 reporteros que cubrían la agitación en los estados norteños de Coahuila y Baja California.

No solo se silencian noticias; también se las inventan. La histeria colectiva se adueñó de la Ciudad de México a consecuencia de las legiones de botsde Twitter que incitaron a la violencia y difundieron información falsa sobre saqueos, cosa que provocó el cierre temporal de unos 20.000 comercios.

«Nunca he visto la ciudad así», confesó Escorcia por teléfono desde su casa en la capital. «Hay más policía de lo normal. Hay helicópteros volando sobre nosotros a todas horas y se escuchan sirenas constantemente. Aunque no ha habido saqueos en esta zona de la ciudad, la gente piensa que está ocurriendo por todas partes».

Escorcia, que lleva siete años investigando el uso de bots en México, cree que las cuentas de Twitter falsas se utilizaron para sembrar el miedo y desacreditar y distraer la atención de las protestas legítimas contra la subida de la gasolina y la corrupción del gobierno. Afirmó haber identificado al menos 485 cuentas que incitaban constantemente a la gente a «saquear Walmart».

«Lo primero que hacen es llamar a la gente a saquear tiendas, luego exigen que los saqueadores sean castigados y llaman a que se eche mano del ejército», explicó Escorcia. «Es un tema muy delicado, porque podría llevar a llamamientos a favor de la censura en internet o a arrestar activistas», añadió, apuntando que la actual administración ya ha pasado por un intento fallido de establecer legislación que bloquee el acceso a internet durante «acontecimientos críticos para la seguridad pública o nacional».

Días después de que el hashtag de «saquear Walmart» se hiciera viral, Benito Rodríguez, un hacker radicado en España, contó al periódico mexicano El Financieroque le habían pagado para convertirlo en trending topic. Rodríguez explicó que a veces trabaja para el gobierno mexicano y admitió que «tal vez» fuera un partido político el que le pagara para incitar al saqueo.

La administración de Peña Nieto lleva mucho tiempo bajo sospecha de utilizar bots con objetivos políticos. En una entrevista con Bloomberg el año pasado, el hacker colombiano Andrés Sepúlveda afirmaba que, desde 2005, lo habían contratado para influir en el resultado de nueve elecciones presidenciales de Latinoamérica. Entre ellas, las elecciones mexicanas de 2012, en las que aseguraba que el equipo de Peña Nieto le pagó para hackear las comunicaciones de sus dos mayores rivales y liderar un ejército de 30.000 bots para manipular lostrending topicsde Twitter y atacar a los otros aspirantes. La oficina del presidente publicó un comunicado en el que negaba toda relación con Sepúlveda.

Los periodistas de México sufren también la amenaza de la violencia de los cárteles. Mientras investigaba Narcoperiodismo, su último libro, Javier Valdez —fundador del periódico Ríodoce— se dio cuenta que hoy día es muy habitual que en las ruedas de prensa de los periódicos locales haya infiltrados chivatos y espías de los cárteles. «El periodismo serio y ético es muy importante en tiempos conflictivos, pero desgraciadamente hay periodistas trabajando con los narcos», cuenta. «Esto ha complicado mucho nuestra labor. Ahora tenemos que protegernos de los policías, de los narcos y hasta de otros reporteros».

Valdez conoce demasiado bien los peligros de incordiar al poder. Ríodoce tiene su sede en Sinaloa, un estado en una situación sofocante cuya economía gravita alrededor del narcotráfico. «En 2009 alguien arrojó una granada contra la oficina de Ríodoce, pero solo ocasionó daños materiales», explica. «He recibido llamadas telefónicas ordenándome que dejase de investigar ciertos asesinatos o jefes narcos. He tenido que omitir información importante porque podrían matar a mi familia si la mencionaba. Algunas de mis fuentes han sido asesinadas o están desaparecidas… Al gobierno le da absolutamente igual. No hace nada por protegernos. Se han dado muchos casos y se siguen dando».

Pese a los problemas comunes a los que se enfrentan, Valdez lamenta que haya poco sentido de la solidaridad entre los periodistas mexicanos, así como escaso apoyo de la sociedad en general. Además, ahora que México se pone en marcha de cara a las elecciones presidenciales del año que viene y continúan sus problemas económicos, teme que la presión sobre los periodistas no haga más que intensificarse, cosa que acarreará graves consecuencias para el país.

«Los riesgos para la sociedad y la democracia son extremadamente graves. El periodismo puede impactar enormemente en la democracia y en la conciencia social, pero cuando trabajamos bajo tantas amenazas, nuestro trabajo nunca es tan completo como debería», advierte Valdez.

Si no se da un cambio drástico, México y sus periodistas se enfrentan a un futuro aún más sombrío, añade: «No veo una sociedad que se plante junto a sus periodistas y los proteja. En Ríodoce no tenemos ningún tipo de ayuda empresarial para financiar proyectos. Si terminásemos en bancarrota y tuviésemos que cerrar, nadie haría nada [por ayudar]. No tenemos aliados. Necesitamos más publicidad, suscripciones y apoyo moral, pero estamos solos. No sobreviviremos mucho más tiempo en estas circunstancias».

Escorcia, que se enfrenta a una situación igualmente difícil, comparte su sentido de la urgencia. Sin embargo, se mantiene desafiante, como en el tuit que publicó tras las últimas amenazas recibidas: «Este es nuestro país, nuestro hogar, nuestro futuro, y solo construyendo redes podemos salvarlo. Diciendo la verdad, uniendo a la gente, creando nuevos medios de comunicación, apoyando a los que ya existen, haciendo público lo que quieren censurar. Así es como realmente podemos ayudar».

Escucha la entrevista a Duncan Tucker en el podcast de Index on Censorship en Soundcloud: soundcloud.com/indexmagazine

Duncan Tuckeres un periodista independiente afincado en Guadalajara, México.

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista Index on Censorship en primavera de 2017.

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Sep 2018 | Asia and Pacific, India, Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.03 Autumn 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102733″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_custom_heading text=”India’s prime minister seeks to create an unquestioning press, writes John Lloyd in the autumn 2018 Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Indian journalism has a strong claim to be the most important journalism in the world. It is still partly free, but increasingly fragile.

US papers and TV channels are routinely vilified by President Donald Trump, and this is both an astounding and a serious matter. So why is India more concerning?

Because the US news media can take care of themselves. And in doing so, take care of the business of truth seeking and telling.

India’s news media, with brave exceptions, are not in that position. The formidably disciplined Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, came to power in 2014, a deserved victory. But in power, Modi made clear that he believes the media need calling to heel.

Hence the litany of proprietors suppressing what might annoy him and the harassment of those who still seek to get out some version of the truth. The phenomenon is familiar: I saw it in Russia, as Vladimir Putin closed in on a chaotic but relatively free journalism.

Modi cannot shoulder all the blame. Corruption – coverage bought by politicians and corporate leaders – long predates him, but has not diminished. The hundreds of news channels, which claim to hold power to account, more often provide space for shouting bouts.

Poverty, violence against women and discrimination against the Muslim minority are often unreported because they are not part of the dominant narrative. The desire of owners, at every level, to pander to the powers that be, seeking to profit by doing so, is too strong.

India claims to be the world’s largest democracy. It is one still: governments change in broadly free elections; opposition can be fierce; the media are curbed but not silenced. The trend, however, is negative. And for what will be soon the world’s largest state, with a prime minister tending to the authoritarian, that matters greatly.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

John Lloyd is a contributing editor to the Financial Times and an author

Index on Censorship’s autumn 2018 issue, The Age of Unreason, asks are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Age Of Unreason” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F09%2Fage-of-unreason%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores the age of unreason. Are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

With: Timandra Harkness, Ian Rankin, Sheng Keyi[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/09/age-of-unreason/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Sep 2018 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.03 Autumn 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Using fiction and stories to influence society is nothing new, but facts are needed to drive the most powerful campaigns, argues Rachael Jolley in the autumn 2018 Index on Censorship magazine” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

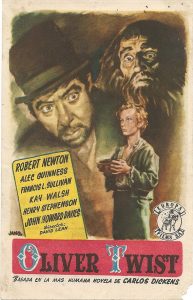

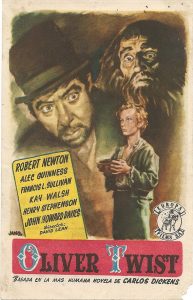

Poster for the 1948 film adaptation of Charles Dickens Oliver Twist (Photo: Ethan Edwards/Flickr)

My friend’s dad just doesn’t believe that UK unemployment levels are incredibly low. He thinks the country is in a terrible state. So when I sit down and say unemployment in 2018 is at 4.2%, the joint lowest level since 1971, he doesn’t really argue. Because he doesn’t believe it.

Well, I say, these are the official figures from the Office for National Statistics. His response is: “Hmm.” Clearly my interjection hasn’t made any difference at all.

He raises an eyebrow to signify, “They would say that, wouldn’t they?”.

This figure, and the picture it sketches, doesn’t chime with his national view, which is that things are very, very bad. And it doesn’t chime with the picture sketched in the newspaper that he reads every day, which is that things are very, very bad.

So, consequently, whatever facts or figures or sources you might throw at him to prove otherwise, nothing makes an impression on him. He believes that the world is the way he believes it is. No question.

Like many people, my friend’s dad reads news stories that reflect what he believes already, and discards stories or announcements that don’t.

And in itself, that is nothing new. For decades people have trusted their neighbours more than people far away. They have read a newspaper that echoed their political persuasion, and sometimes they have felt that the society they lived in was worse than it used to be, even when all the indicators showed their lives had improved.

Often humans believe in ideas by instinct, not because they are presented with a graph. In 2005, Drew Westen, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at Emory University, in Atlanta, USA, published The Political Brain. In it, he argued that the public often made decisions to support political parties based on emotions, not data or fact.

The book struck home with activists, who tried to utilise Westen’s thinking by changing the way they campaigned. Politicians had to capture the public’s hearts and minds, Westen said. He talked about the role of emotion in deciding the fate of a nation and gave examples. When US President Lyndon Johnson proposed the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which outlawed racial discrimination at the US ballot box, he used personal stories to make his points stronger, said Westen, adding that this was a powerful tool. In doing so, Westen was ahead of his time in acknowledging just how strongly humans value emotion, and how an emotional action can be driven by feeling and desire rather than the latest data from a governmental body.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The articulation of ideas through emotional stories, though, is really no different from Charles Dickens sketching the harsh world of the children in workhouses in Oliver Twist” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Westen used his thesis to show why he felt US Democratic candidates Al Gore and Michael Dukakis had failed to get elected, and why George W Bush had. Bush, he felt, was in touch with his emotional side while Dukakis and Gore tended to turn to dry data and detail.

That argument about how emotional beliefs or gut feelings are being used to influence important decisions has raced up the agenda since President Donald Trump arrived in the White House, the UK voted for Brexit and with the use of emotionally driven political campaigns to shift public opinion in Hungary and Poland.

Suddenly this question of why people were responding to appeals to emotion and dismissing facts was the debate of the moment. In many ways this is nothing new but the methods of receiving ideas and information are different. Now we have Facebook and Instagram posts, and zillions of tweets to spin and challenge.

One part of it, the articulation of ideas through emotional stories, though, is really no different from Charles Dickens sketching the harsh world of the children in workhouses in Oliver Twist, or Victorian writer Charles Kingsley’s story The Water Babies. Kingsley’s tale of child chimney sweeps helped to introduce the 1864 Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act, which improved the lives of those children significantly.

Fictional stories, like these, have always played a part in changing attitudes, but also draw on reality. Dickens and Kingsley were outraged by the living and working conditions they saw, so they chose to try to effect change by using fictional stories to engage a wider public. And personal stories are also used to illuminate wider factual trends. For years journalists have used a case study as an explainer for something more detailed.

Facts and figures undoubtedly must have a role. Even when it appears there is public resistance to acceptance of data, something such as the fact that if you wear a seatbelt when driving a car you will have a better chance of surviving an accident becomes an accepted truth over time. Public information and published statistics clearly play a part in that shift.

That’s why it is so vital that public access to information is protected and that incorrect facts are challenged. This month, 28 September is the international day for universal access to information, something that concentrates the mind when you look at places where access is limited, or where government data is skewed to such a level that it becomes almost pointless.

Journalists reporting in countries including Belarus and the Maldives tell us their quest for trustworthy sources of national information are almost impossible to find as their governments refuse to respond to media requests or release untrue information. Officials also use smear tactics to undermine reporters’ reputations, so their accurate journalism is not believed. Governments know that by keeping information from the media they hamper a journalist’s ability to report, and in doing so may keep a scandal from the public. If facts and data didn’t make a difference, those governments would have no reason to restrict access.

Freedom to access information goes hand in hand with freedom of the media and academic freedom in creating an open democratic society. But at Index, we constantly see signs of governments, and others, trying to prevent both access to facts and to suppress writing about inconvenient truths.

In this issue of the magazine, we explore all aspects of this struggle to balance facts and emotion, the quest to find the truth, how we are influenced, and why arguments, debates and discussions are so vital.

There’s lots to read, from Julian Baggini’s piece (p24) on why people might fear a disagreement to tips on how to have an argument from Timandra Harkness (p31). Then there’s Martin Rowson’s Stripsearch cartoon (p26). Our interview with British TV presenter Evan Davis discusses whether lies tend to be found out over time, and the likelihood that people will select facts that support their political position.

What’s it like to be a scientist in the USA right now? Michael Halpern from the Union of Concerned Scientists in the USA says scientists are suddenly getting active to push back against a political climate attempting to take the factfile away from important government departments.

Almost every day a new story pops up outlining another attack on media freedom in Tanzania, and in this issue Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein reveals how bloggers are being priced out of the country (p70) as the government uses new fees to close down independent voices.

Then there’s Nobel prize winner Herta Müller on her experiences of censorship as a writer living in communist Romania (p67), and Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s poems written in prison (p86).

And finally, look out for our Banned Books Week events coming up at the end of September – find out more on the website. You’ll also find the magazine podcast, with interviews with broadcaster Claire Fox and Tanzanian blogger Elsie Eyakuze, on Soundcloud, and watch out for your invitation to the upcoming magazine event at the Royal Institution in October.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on The Age Of Unreason.

Index on Censorship’s autumn 2018 issue, The Age Of Unreason, asks are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Age Of Unreason” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F09%2Fage-of-unreason%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores the age of unreason. Are facts under attack? Can you still have a debate? We explore these questions in the issue, with science to back it up.

With: Timandra Harkness, Ian Rankin, Sheng Keyi[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/09/age-of-unreason/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]