22 Aug 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society

Egypt faced a new phase of uncertainty after the bloodiest day since its Arab Spring began, with nearly 300 people reported killed and thousands injured as police smashed two protest camps of supporters of the deposed Islamist president. (Photo: Nameer Galal / Demotix)

Nearly 1,000 people have been killed in Egypt in a week of deadly violence that began with a brutal security crackdown on Islamist protesters staging two sit ins in Cairo to demand the reinstatement of the country’s first democratically-elected president Mohamed Morsi . Six weeks earlier, Morsi had been removed from office by the military after millions of Egyptians took to the streets calling on him to step down and hold early presidential elections. Ever since the military takeover, hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters have been killed or arrested as the Egyptian military and police pursue what they describe as an “anti- terrorism drive”.

The majority of Egyptians have expressed their support for the military and police , cheering them on in their sweeping campaign “to rid the country of the scourge of terrorism” and at times, launching verbal and physical attacks on the pro-Morsi protesters. Islamist supporters of the deposed president have meanwhile continued to stage rallies across the country, condemning the violence.

Egyptian media has also chosen to side with the country’s powerful security apparatus and has consistently glorified the military while demonizing the toppled president’s supporters. The text “Together against terrorism” appears on the bottom corner of the screen on most state and independent TV channels. In this bitterly polarized and often dangerous environment, it is the journalists covering the unrest that are caught in the middle, facing detention, intimidation, assault and sometimes, even death.

Tamer Abdel Raouf, an Egyptian journalist who worked for the state sponsored Al Ahram newspaper last week became the fifth journalist to die in the unrest when he was shot by soldiers at a military checkpoint “for failing to observe the nighttime curfew.” Abdel Raouf had been driving in Al Beheira when he was ordered by soldiers to turn back. While the soldiers claim he did not heed the warnings , another journalist accompanying him in the car said that Abdel Raouf had in fact been making a U turn when the soldiers fired their guns , instantly killing him. Prior to his death, he had persistently criticized the manner in which “the legitimate” president was ousted.

Other Egyptian journalists critical of the coup have meanwhile, faced intimidation and threats. The handful of Egyptian journalists who have remained unbiased, refusing to take sides in the conflict, have faced the wrath of an increasingly intolerant public that has labelled them “traitors” and “foreign agents.” A reporter working for an international news network who chooses to remain anonymous, told Index she had received threats via her Facebook account urging her to “remain quiet or be silenced forever.” The messages were sent by people claiming affiliations with Egypt’s security apparatus including the Egyptian intelligence , she said. “You will be made to pay for your stance,” read one message while another warned she would be physically attacked for being “a traitor and an enemy of the state.”

However, it is Western journalists that are bearing the brunt of the mounting anger in the deeply divided nation. The government has accused them of “being biased” in favor of the Islamists and of failing to “understand the full picture”.

“Some Western media coverage ignores shedding light on violent and terror acts that are perpetrated by the Muslim Brotherhood in the form of intimidation operations and terrorizing citizens,” a statement released by the State Information Service (SIS), the official foreign press coordination center said. SIS officials have also affirmed that no ‘coverage authorizations’ would be granted to foreign journalists unless they receive prior approval from Egyptian intelligence –a marked shift meant to restrict coverage to “journalists who have not ruffled the feathers of the authorities,” an SIS official who does not wish to be named, disclosed.

Meanwhile, in recent meetings with representatives of foreign media outlets, Foreign Minister Nabil Fahmy and presidential spokesman Ahmed Mosslemany have accused the Western press of conveying a “distorted image” of the events in Egypt. They urged the journalists to rein in their criticism of the government and to try and “see the full picture”. “Why is the Western media not covering the ‘terror’ acts committed by the Muslim Brotherhood including attacks on churches and police stations instead of devoting their coverage to assaults by security forces on pro-Morsi protesters?” they quizzed.

Western journalists deny that their coverage has been one-sided insisting that they had travelled to southern provinces where sectarian violence is rampant. Several foreign reporters have meanwhile, been subjected to harassment, assaults and detentions by security forces and popular vigilante groups while covering the recent clashes between pro-Morsi protesters and security forces.

Last Saturday marked a day of increased violence against Western journalists with at least six foreign correspondents reporting harassment and assaults while attempting to cover the siege on a mosque in downtown Cairo where pro_Morsi protesters had sought refuge after clashes with security forces. Two foreign journalists –the Wall Street Journal’s Matt Bradley and Alastair Beach, a correspondent with the Independent –sustained minor injuries when they were attacked by assailants outside the mosque but army soldier momentarily intervened, shielding them from the angry mob and dragging them to safety. Patrick Kingsley, a correspondent for the Guardian, was meanwhile, briefly detained and questioned by several suspicious vigilante groups and by police as he attempted to cover the mosque siege on Saturday. He later complained on Twitter that his equipment –including a laptop and cell phone– was seized in the process.

Abdulla Al Shami, a correspondent with Al Jazeera who was detained on Wednesday 14 August while covering the security crackdown on the Rab’aa pro-Morsi sit in, remains in police custody at an undisclosed location, according to the New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists. Mohamed Badr, a photographer working for the news channel has meanwhile been in detention since July 15 on the charge of possessing weapons—an accusation denied by Al Jazeera. Moreover, the offices of Al Jazeera Arabic were ransacked and shut down by police last week . Egyptian authorities are considering suspending Al Jazeera Mubasher’s license, accusing the network of “a clear pro-Morsi bias ” according to state owned Al Ahram newspaper. Many Egyptians are also accusing Al Jazeera of “inciting violence “ and of “threatening national security.”

The stepped up attacks on foreign journalists come at a time when the new interim government faces a chorus of international condemnation over its handling of the current political crisis. Clearly determined to crush the Muslim Brotherhood , the authorities remain defiant rejecting all attempts at reconciliation with the Islamists as “meddling in the country’s internal affairs.” Anyone remotely suggesting that the military should reconcile with the Muslim Brotherhood, the long detested arch-enemy, is accused of being a “traitor” and a “threat to the nation’s security”. Hence, the legal complaints recently filed against Vice President for Foreign Affairs Mohamed El Baradei who resigned his post earlier this month after security forces forcibly broke up the pro_Morsi sit ins.

In the divided country, Egyptians have adopted an uncompromising attitude of “you are either with us or against us”. The government has meanwhile encouraged such attitude by praising and rewarding “the patriots”. In such an atmosphere, there is no room for objectivity and any neutral media that reports without bias is accused of being pro-Islamist and perceived as “the enemy”.

Reverting back to Mubarak-era tactics, the government is determined to silence the voices of dissent.

15 Aug 2013 | Comment, Egypt, News and features

Egypt faced a new phase of uncertainty after the bloodiest day since its Arab Spring began, with nearly 300 people reported killed and thousands injured as police smashed two protest camps of supporters of the deposed Islamist president. (Photo: Nameer Galal / Demotix)

As the numbers steadily mount of those killed by the Egyptian military and police in yesterday’s attacks on Muslim Brotherhood camps, the prospects for Egypt’s ‘Arab spring’ are looking bleak.

The violent destruction of the two camps, and the indiscriminate shootings, beatings and arrests of supporters of ousted President Mohamed Morsi, and of journalists, was clearly planned. The country’s military rulers have taken little time to demonstrate their contempt for the many Egyptians who wrongly thought the army could usher in a more pluralist rights-respecting democracy. The hopes of those who saw July’s coup as somehow too positive to warrant such a label now lie in tatters, with Mohamed ElBaradei’s inevitable resignation just one small illustration of that.

Is this simply a return to square one – back to a Mubarak-style, military-run Egypt? At one level surely it is, with army head General al-Sisi showing neither shame nor compunction in such a murderous installation of the new state of emergency.

But while the similarities to the Mubarak era are clear, this is a new and different Egypt. The millions who demonstrated in Tahrir Square in 2011, and again this June in protest at President Morsi’s authoritarian approach to government, are not simply going to accede to corrupt and vicious military rule once more. And the brutal violence against the Muslim Brotherhood protesters is most likely to beget more violence rather than the destruction of the Brotherhood that the army appears intent on.

With the violent face of the new Egyptian regime now clearly on display to the whole world, with no respect for rights of protesters, or media, or ordinary citizens, the international response has been shamefully muted. The EU’s foreign policy supremo, Cathy Ashton, called for the military to exercise the “utmost restraint” and for an end to the state of emergency “as soon as possible, to allow the resumption of normal life”. Meanwhile Samantha Power, Obama’s UN ambassador, tweeted weakly that the “forcible removal” of protesters was “a major step backward”.

Earlier in the week, the US and EU failed in their mediation attempts to stop the attacks on the camps, that all could see were coming. The key question now should be whether they are prepared to go for tougher diplomacy in an attempt to exert some leverage on the disastrous social and political dynamics that have now been unleashed so far. This would have to revolve around suspension of the $1.3 billion of military aid the US gives Egypt each year.

Obama’s first statement of condemnation finally came today but with no hint of the sort of leadership or signal that suspension of aid would send. Obama’s cancellation of military exercises next month will not worry Egypt’s generals much. And his uplifting speech on a new beginning at Cairo University in 2009 – and his Nobel Prize that year – are surely now lost in the dust and ashes of the aftermath of Wednesday’s violence and the US’s refusal to use the tools of influence it has. For now, more urgent and serious statements are coming rather from the UN.

Whether Egypt’s citizens who demonstrated for an end to military rule, and for a genuine pluralist democracy can regroup enough to have the influence to stop the downward spiral looks doubtful. But the spirit of Tahrir Square did not die yesterday. And if Egypt is now in winter, then spring at some point must come again. But for now the winter looks to be just beginning.

This article was originally published on 15 Aug 2013 at indexoncensorship.org. Index on Censorship: The voice of free expression.

14 Aug 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

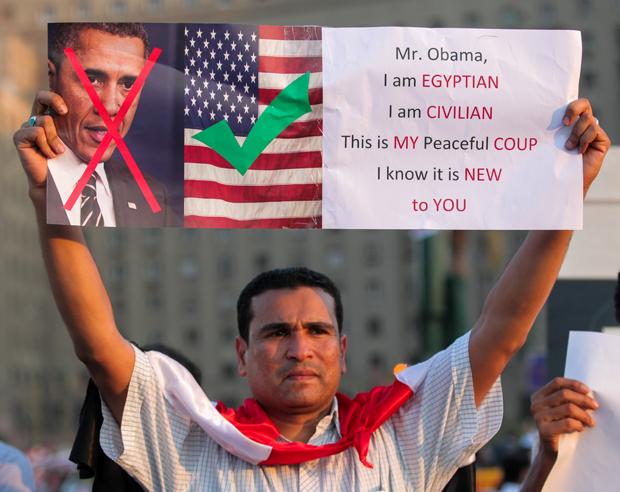

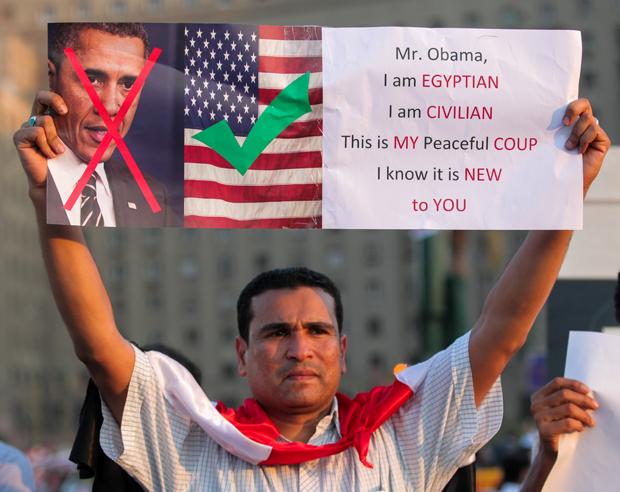

An Egyptian protestor holds a sign showing the anger of some Egyptian people towards the American government. (Photo: Amr Abdel-Hadi / Demotix)

Index on Censorship condemns today’s attacks on protest camps in Cairo and other cities and calls on Egyptian authorities to respect the right to peaceful protest. Live coverage Al Jazeera | BBC | The Guardian

Xenophobia in general and anti-US sentiment, in particular, have peaked in Egypt since the June 30 rebellion that toppled Islamist President Mohamed Morsi and the Egyptian media has, in recent weeks, been fuelling both.

Some Egyptian newspapers and television news has been awash with harsh criticism of the US administration perceived by the pro-military, anti-Morsi camp as aligning itself with the Muslim Brotherhood. The media has also contributed to the increased suspicion and distrust of foreigners, intermittently accusing them of “meddling in Egypt’s internal affairs” and “sowing seeds of dissent to cause further unrest”.

A front page headline in bold red print in the semi-official Al Akhbar newspaper on Friday 8 Aug proclaimed that “Egypt rejects the advice of the American Satan.” The paper quoted “judicial sources” as saying there was evidence that the US embassy had committed “crimes” during the January 2011 uprising, including positioning snipers on rooftops to kill opposition protesters in Tahrir Square.

The stream of anti-US rhetoric in both the Egyptian state and privately-owned media has come in parallel with criticism of US policies toward Egypt by the country’s de facto ruler, Defense Minister Abdel Fattah el Sissi, who in a rare interview last week, told the Washington Post that the “US administration had turned its back on Egyptians, ignoring the will of the people of Egypt.” He added that “Egyptians would not forget this.”

Demonizing the US is not a new trend in Egypt. In fact, anti-Americanism is common in the country where the government has often diverted attention away from its own failures by pointing the finger of blame at the United States. The public has meanwhile, been eager to play along, frustrated by what is often perceived as “a clear US bias towards Israel”.

In Cairo’s Tahrir Square, anti-American banners reflect the increased hostility toward the US harboured by opponents of the ousted president and pro-Morsi protesters alike, with each camp accusing the US of supporting their rivals. One banner depicts a bearded Obama and suggests that “the US President supports terrorism” while another depicts US ambassador to Egypt Anne Patterson with a blood red X mark across her face.

The expected nomination of US Ambassador Robert Ford — a former ambassador to Syria who publicly backed the Syrian opposition that is waging war to bring down the regime of Bashar El Assad — to replace Patterson, has infuriated Egyptian revolutionaries, many of whom have vented their anger on social media networks Facebook and Twitter. In a fierce online campaign against him by the activists, Ford has been criticized as the “new sponsor of terror” with critics warning he may be “targeted” if he took up the post. Ambassador Ford who has been shunned by the embattled Syrian regime, has also been targeted by mainstream Egyptian media with state-owned Al Ahram describing him as “a man of blood” for allegedly “running death squads in Iraq” and “an engineer of destruction in Syria, Iraq and Morocco.” The independent El Watan newspaper has also warned that Ambassador Ford would “finally execute in Egypt what all the invasions had failed to do throughout history.”

The vicious media campaign against Ford followed critical remarks by a military spokesman opposing his possible nomination. “You cannot bring someone who has a history in a troubled region and make him ambassador, expecting people to be happy with it”, the spokesman had earlier said.

Rights activist and publisher Hisham Qassem told the Wall Street Journal last week that “Egyptian media often adopts the state line to avoid falling out of favour with the regime.”

Statements by US Senator John McCain who visited Egypt last week to help iron out differences between the ousted Muslim Brotherhood and the military, have further fuelled the rising tensions between Egypt and the US. McCain suggested that the June 30 uprising was a “military coup”, sparking a fresh wave of condemnation of US policy in the Egyptian press.

“If it walks like a duck, quacks like a duck, then it’s a duck,” Senator John McCain had said at a press briefing in Cairo. He further warned that Egypt was “on the brink of all-out bloodshed.” The remarks earned him the wrath of opponents of the toppled president who protested that his statements were “out of line” and “unacceptable.” The Egyptian press meanwhile has accused him of siding with the Muslim Brotherhood and of allegedly employing members of the Islamist group in his office.

The anti-Americanism in Egypt is part of wider anti-foreign sentiment that has increased since the January 2011 uprising and for which the media is largely responsible. Much like in the days of the 2011 uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak, the country’s new military rulers are accusing “foreign hands” of meddling in the country’s internal affairs, blaming them for the country’s economic crisis and sectarian unrest. The US has also been lambasted for funding pro-reform activists and civil society organizations working in the field of human rights and democracy.

Ahead of a recent protest rally called for by Defense Minister Abdel Fattah El Sissi to give him “a mandate to counter terrorism”, the government warned it would deal with foreign reporters covering the protests as spies. As a result of the increased anti-foreign rhetoric in the media, a number of tourists and foreign journalists covering the protests have come under attack in recent weeks. There have also been several incidents where tourists and foreign reporters were seized by vigilante mobs looking out for “spies” and who were subsequently taken to police stations or military checkpoints for investigation. While most of them were quickly freed, Ian Grapel — an Israeli-American law student remains in custody after being arrested in June on suspicion of being a Mossad agent sent by Israel to sow “unrest.”

Attacks on journalists covering the protests and the closure of several Islamist TV channels and a newspaper linked to the Muslim Brotherhood do not auger well for democracy and freedoms in the new Egypt. The current atmosphere is a far cry from the change aspired for by the opposition activists who had taken to Tahrir Square just weeks ago demanding the downfall of an Islamist regime they had complained was restricting civil liberties and freedom of speech.

The increased level of xenophobia and anti-US sentiment could damage relations with America and the EU at a time when the country is in need of support as it undergoes what the new interim government has promised would be a “successful democratic transition.”

This article was originally published on 14 Aug, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org. Index on Censorship: The voice of free expression

7 Aug 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, Turkey, Turkey Statements

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Photo: Philip Janek / Demotix)

While Turkey this week jailed its former Chief of Staff, General Ilker Basbug, in Egypt, General Sisi’s popularity is still riding high following the army’s ousting of President Morsi.

Yet the mass prosecutions and heavy sentencing under the so-called Ergenekon case in Turkey do not simply show a welcome assertion of civilian over military power. Nor does the military’s role in Egypt constitute what US secretary of state John Kerry rather remarkably referred to a week ago as “restoring democracy” – contradicted this week by John McCain for the first time calling the coup a coup.

Both Turkey and Egypt have failed so far to find a way to reconcile democracy, Islam, and the role of the military. And while a big segment of the Egyptian population is now rashly putting its faith in its army to lead it to a fully functioning pluralist democracy, Turkey’s recent past shows precisely why that might result in modernisation but not democracy.

Yet the recent protests in both countries also show that majoritarian democracy, without respect for the rule of law, human rights, and media freedom, will not lead to a fair, open and stable democratic system either. Where Turkey was once seen as the poster boy for democracy in a Muslim majority country, that picture is now truly tarnished. But the route via military power will never make a good alternative model.

The Military and Kemalism

Turkey for decades followed a path – led by its military and various Kemalist and secularist supporters – of modernisation and westernisation, a sort of quasi-democracy with the military there as a ‘guard rail’ against Islamists and other ‘enemies’ of the state. This army-protected approach did little to propel democracy though it led to some substantial economic and social modernisation especially in the west of Turkey (though its neglect of the smaller businesses of central Anatolia was one part of Erdogan’s remarkable success when he swept to power in 2002).

But, without proper political accountability or a genuinely independent judiciary and free media, corruption and the ‘deep state’ grew and prospered in Turkey tying together a range of unlikely bedfellows, while labelling as dangerous enemies a range of people from Islamists to Kurds, leftists and Alevis with civil society, academics and independent journalists seen as at best deeply suspicious too.

Turkey’s last military coup was in 1980 but the so-called ‘soft coup’ of 1997 pushed the Justice and Development Party (AKP)’s predecessor out of power. Frustrated and oppressed by military-backed politics, when Erdogan’s Islamist-leaning AKP came into power in 2002, many liberals welcomed it as heralding and introducing major steps forward in starting to create a genuinely pluralist democracy, one that would respect minorities, seriously tackle Turkey’s appalling record of torture, and open up the prospect of finally replacing the 1982 military-imposed constitution.

The nationalist-secularist deep state was less impressed fearing underlying Islamist intentions. But attempts at an ‘e-coup’ in 2007 (through military expressed disapproval of the Erdogan government) to the attempted banning of the AKP in the ‘judicial coup’ of the following year failed. And so over his eleven years in power, Erdogan has asserted increasing civilian control over the military.

But the over-reach in the Ergenekon trials, with a wide range of observers criticising the politicisation of the prosecution, lack of due process, and the severity of the sentencing, some labelling it a witch hunt, suggest a process more of political revenge or what commentator Cengiz Candar labels “civilian authoritarianism” rather than a democratic breakthrough. With only 21 acquitted from 275 defendants, in a very wide set of charges around terrorism and coup plots, the Ergenekon sentences mark a moment of deepening political division in Turkey. The draconian nature of the sentences against several journalists and writers have been severely criticised by Dunja Mijatovic, the OSCE’s freedom of the media representative and condemned by the Association of European Journalists.

As this more authoritarian Turkish democracy has developed over the last five years, Turkey’s media has become ever less independent, ever more crushed or complicit – with more journalists in jail than in China and Iran, and sacking of columnists and editors rife even before the surge in dismissals that followed the recent Gezi Park protests and the Ergenekon imprisonments.

Nor has Erdogan stopped at media pressure and control. Turkey has a weak record on internet freedom too. The European Court of Human Rights ruled in May this year that Turkey’s blanket blocking of sites violated freedom of expression – a ruling that will doubtless not have impressed Erdogan and his ministers who were so outraged by free speech on Twitter and other social media during the recent protests.

But it would be hard to argue that Turkey would be better off today if it reverted to its old, failed ways of military coups and a corrupt, elitist deep state. Turkey needs a truly independent, impartial and honest judiciary, a free, strong media to hold politicians to account, a free and open internet. And it also needs healthy dynamic opposition parties too. Yet the recent mass protests showed only too clearly that the stumbling Republican People’s Party (CHP) has still failed to find a convincing modern democratic voice, even as Erdogan has shifted from progressive to more authoritarian ways. The masses of protesters – looking for a more genuine, pluralist democracy – still lack serious political parties to work through.

It is a vicious circle – as the lack of dynamic opposition parties interacts with the ever crumbling, no longer independent media, government over-reach and the failure to introduce a modern constitution respecting human rights, free speech, and an independent judiciary.

Any Lessons for Egypt?

It is this sort of majoritarianism democracy, but worse, that Egypt has now supplanted with its own protest-backed military coup. Morsi’s government had lurched into an authoritarianism that went a long way beyond where Erdogan has taken Turkey. Where Erdogan failed to introduce a new constitution, Morsi rammed one through that undermined any hopes of establishing a genuine pluralist democracy with full respect for human rights for all.

But the omens for Egypt’s coup as a pro-democracy move are not good. The military have moved rapidly to restore in full public sight various secret police groups. Muslim Brotherhood politicians, including Morsi, are in jail, protesters have been shot and killed – often in the head or chest in what many have called a massacre. And media are being watched, with those sympathetic to the Muslim Brotherhood closed down or censored. This week 75 judges were questioned about their political sympathies for the Brotherhood – a step the Turkish deep state would have only applauded and concurred with. The so-called Third Square movement, attempting to create support for a new democratic path that supports neither military nor Morsi, is so far small compared to the other two camps.

The US, EU and Arab diplomats are now stepping in urgently – attempting to stop a lurch into indefinite and widespread violence, and to stop further killings as the Egyptian authorities threaten to close down the two Brotherhood protest camps in Cairo. But today disturbingly the interim presidency said these efforts have failed – more violence may well loom.

The same challenge

In the end both Turkey and Egypt face the same challenge: how to get to a fully functioning democracy, with rights for all not just the majority. It cannot be done through military coups, violence and military-backed modernisation. It cannot be done through street protests alone. And where Erdogan’s AKP in 2002 showed a possible way ahead, that model now lies in tatters as Erdogan has shed his progressive mantle.

Yet the tools and the vital steps are not a mystery; they include a free and independent media, full respect for human rights, an independent judiciary, and a vibrant set of political parties. The political challenge is how to create and defend those tools; that is the big task for progressive civil society and for genuinely democratic politicians in both countries – and for their supporters in other countries.