Iran’s erased women remembered

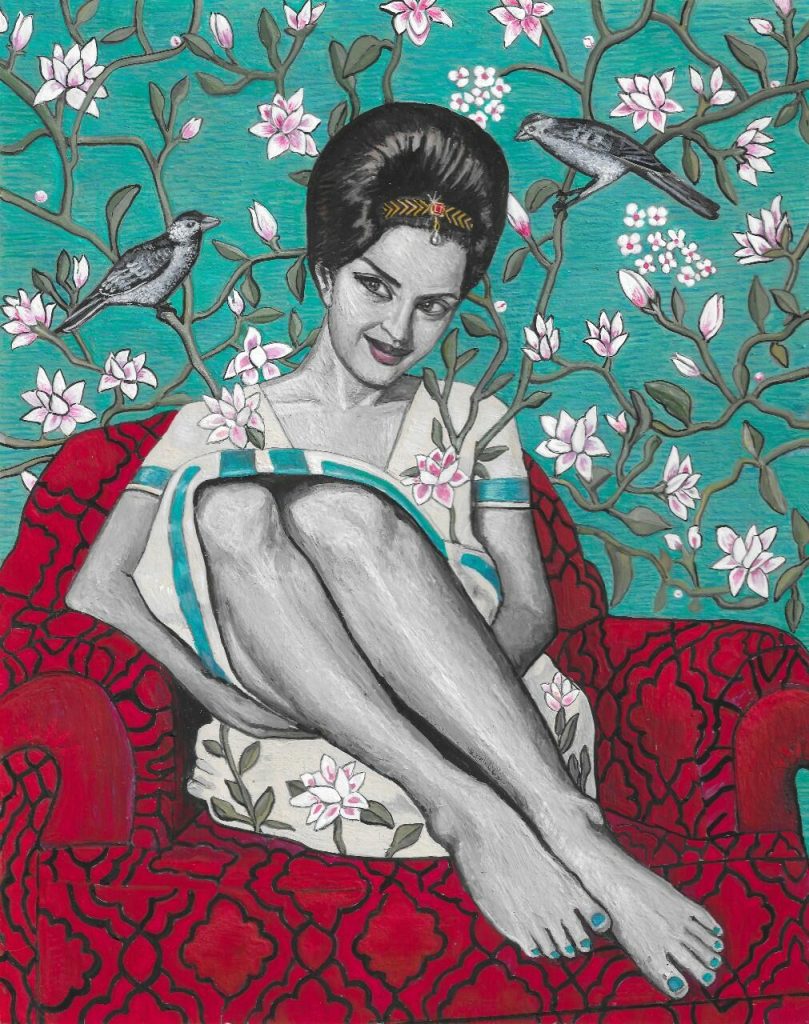

Wild at Heart (Portrait of Pouran Shapoori), 2019 Credit: Soheila Sokhanvari, courtesy Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

The long, winding path of The Curve art gallery at London’s Barbican Centre has been transformed into a devotional space. The cavernous room is dimly lit and echoes with the calming voices of female Iranian singers. Sprawling, Islamic, geometric patterns roll down the tall walls which are splintered with the light projected onto them by dazzling mirrored sculptures. Apart from the female voices, it feels like a mosque.

Take a closer look, and the walls are scattered with traditional Persian miniatures, depicting women whose histories have been erased in Iran. In painstaking detail, Soheila Sokhanvari’s portraits provide a snapshot into women’s lives pre-revolution. Born in Shiraz in the Fars Province of Iran, she came to England in 1978, just a year before the Islamic Revolution. But Sokhanvari remains enchanted with the country she left behind. Her miniatures depict unveiled and glamorous women, creative dissidents who pursued careers in a country awash with Western style but not its freedoms.

“I can relate directly to the women in my paintings,” she told Index. “Like them I am an artist but, unlike them, I am able to pursue my career, wear what I want and act as I want, and the idea that one day someone could take my freedom away from me is unthinkable”.

The portraits are displayed without names or biographical info but, by scanning a QR code, we are guided through the exhibition by their stories. There are 28 in total: actors, singers, poets, writers, dancers and film directors, all of which were either forced into silence or exile in 1979, when the Islamic Revolution led to a rollback in women’s legal rights. Much of their work is censored in Iran today. “I knew of many of the women from my own experience and time in Iran as a young girl,” Sokhanvari explained. “They were my idols, but finding out more information about the lives of several of the women took lots of research – they were essentially erased from the record by the regime”. She said that a small number of the women – like singer and actress Googoosh – are very famous, but that several had tragically died too young and were hard to trace.

The exhibition draws the spotlight back onto these talented women for which, she says, she feels a deep loss. The portraits beautifully capture this feeling: a simultaneous celebration of their bravery and a mourning of their freedoms. Vivid patterns and clothing contrast monochromatic faces, which make the pictures feel both vibrant and ghostly. The use of new and old multimedia was significant in telling these stories too. “I painted my portraits in the ancient technique of egg tempera, onto calf vellum, and I included films in which the women starred, ” Sokhanvari said. Two holograms of dancing Iranian actors Kobra Saeedi and Jamileh are also hidden in boxes. “I wanted the viewers to see these women, to watch them dance and to hear them sing, since they have been banned from these platforms.” The broadcasting of women’s voices in public is illegal in Iran. “I wanted to show these women at the height of their creativity, to show them as the sensational artists that they are, and using multimedia helped to achieve this immersive experience.”

This contrast of old and new is fitting. While the exhibition was curated without sight of the current unrest in Iran, the portraits certainly gain a tragic poignancy because of it. The brave women of Sokhanvari’s portraits embody much of what people are fighting for today. “Young women are at the front of this revolution and that is what gives it its power,” she told Index. “I feel a new sense of positivity and hope that perhaps we will see the end of this regime, but simultaneously I feel pain and bitterness that it is at the cost of so many bright lives.”

Although she doesn’t describe her artwork as a protest, she says that the message is political.

“What is happening in Iran can no longer be seen as just another protest, it is a revolution and I stand in solidarity with my sisters.” I asked if her portraits reflect a lost past or a hopeful future. She says both.

‘Rebel Rebel’ at The Curve, Barbican is open until 26 February 2023

Seeing Auschwitz is a timely reminder of the importance of documenting atrocities

A new exhibition in London takes a different viewpoint on the horrors of the Holocaust

Landmark report finds China using arts “to silence critics and drive censorship”

A new report from Index on Censorship published today (Thursday, December 1st) has laid bare the shocking extent to which Chinese Communist Party (CCP) activity is driving a new era of artistic censorship across Europe.

The report – Whom to Serve? How the CCP censors art in Europe – builds on in-depth interviews with more than 40 leading artists, curators, academics and experts from across Europe, and the findings of more than 35 Freedom of Information requests. It paints a worrying picture of the coordinated campaign by the CCP to undermine artistic freedoms.

Key findings include:

- Ruthless CCP techniques to limit the spread of critical art, including diplomatic pressure, direct threats to individuals and the propagation of pro-state art.

- A concerted drive to impose self-censorship on artists working in Europe, including surveillance, interrogations, graffiti and physical attacks.

- Threats made to those with family in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

- The spread of CCP soft power from visual arts into fine art, sculpture, graphic art, film, fashion and theatre.

- A murky network of extensive financial and non-financial ties between Chinese companies and state bodies, and European art institutions, the full scale of which is almost impossible to ascertain.

Jemimah Steinfeld, editor-in-chief at Index, said:

“With the kidnapping of a Hong Kong bookseller in Thailand nine years ago, we have long known that the CCP’s police state stretches beyond its own borders. But what this report shows in startling detail is just how far it stretches and how common aggressive tactics are.

“The scale of the CCP’s reach across the arts world is as staggering as its nature is coordinated. This is not a fringe pursuit or some dabbling at the margins – it is a new and growing weapon in China’s arsenal to burnish its image abroad, control how people both view it and discuss it, and to ruthlessly target those who create or curate art they class as dangerous.

“European art galleries and museums are relentlessly targeted by the CCP using a variety of tools. From diplomatic pressure aimed at European artistic institutions to cancel or forcibly change exhibitions, to the championing of a counter-narrative through artistic work that amplifies state propaganda, there is a battle being fought in institutions across Europe.

“With the recent re-entrenchment of Xi Jinping’s leadership and the growth of China as the 2nd largest art market, there are no signs of the CCP stopping.”

The report shows how the CCP targets dissident artists with overt censorship to prevent critical artwork from being made public, and self-censorship to dissuade artists and institutions from taking the risk of criticising both the party and the country. Fear of reprisals against both themselves and their family pushes many artists, even those living in Europe, to avoid sensitive topics.

While large-scale and coordinated, the report shows the CCP’s efforts to be only partially successful. While self-censorship is rife, attempts to pressure European governments to censor artists has largely failed, even in the face of financial hits to both private galleries or museums.

Nik Williams, policy and campaigns officer, Index on Censorship, added:

“With China one of the world’s largest and most rapidly expanding markets for contemporary art, there are also increasing connections between European art institutions and Chinese state linked firms or individuals sympathetic to the CCP.

“The difficulties we faced in tracking and tracing these connections, murky in their nature and opaque in their arrangements, is concerning in itself. We remain fearful of how these relationships could inform how institutions engage with dissident artists or sensitive topics.”

ENDS

NOTES TO EDITORS

- You can read the full report, “Whom to Serve?: How the CCP censors art in Europe”, here

- The report includes exclusive artwork from leading dissident artist, Badiucao, as well as pieces from Lumli Lumlong, Jens Galschiøt and Yang Weidong.

For press and broadcast interview requests, or for further information, please contact:

Luke Holland // [email protected] // +44 7447 008098