4 Sep 2018 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 47.03 Autumn 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Ian Rankin, Herta Müller, Peter Sands, Timandra Harkness, David Ulin, John Lloyd, Sheng Keyi and Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The autumn 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the ways in which we might be turning away from facts and science across the globe.

We examine whether we have lost the art of arguing through Julian Baggini‘s piece on the dangers of offering a different viewpoint, and the ways we can get this art back through Timandra Harkness‘ how-to-argue guide. Peter Sands talks about the move towards more first person reporting in the news and whether that is affecting public trust in facts, while Jan Fox talks to tech experts about whether our love of social media “likes” is impacting our ability to think rationally.

We also go to the areas of the world where scientists are directly under threat, including Hungary, with Dan Nolan interviewing academics from the Hungarian Academy of Scientists, Turkey, where Kaya Genç discusses the removal of Darwin from secondary school education, and Nigeria, where the wellness trend sees people falling as much for pseudoscience as actual science, writes Wana Udobang.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102490″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Outside of the special report, don’t miss our Banned Books Week special, featuring interviews with Kamila Shamsie, Olga Tokarczuk and Roberto Saviano. We also have contributions from Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o on his time in prison and how that might have shaped his creativity and Nobel Prize-winning writer Herta Müller on being questioned by Romanian secret police.

Finally, do not miss best-selling crime writer Ian Rankin‘s exclusive short story for the magazine and poems written by imprisoned British-Iranian mother Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, which are published here for the first time.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report: The Age of Unreason”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Turkey’s unnatural selection, by Kaya Genç: Darwin is the latest victim of an attack on scientific values in Turkey’s education system

An unlikeable truth, by Jan Fox: Social media like buttons are designed to be addictive. They’re impacting our ability to think rationally

The I of the storm, by Peter Sands: Do journalists lose public trust when they write too many first-person pieces?

Documenting the truth, by Stephen Woodman: Documentaries are all the rage in Mexico, providing a truthful alternative to an often biased media

Cooking up a storm, by Wana Udobang: Wellness is finding a natural home in Nigeria, selling a blend of herbs – and pseudoscience

Talk is not cheap, by Julian Baggini: It’s only easy speaking truth if your truth is part of the general consensus. Differing viewpoints are increasingly unwelcome

Stripsearch, by Martin Rowson: Don’t believe the experts; they’re all liars

Lies, damned lies and lies we want to believe, by Rachael Jolley: We speak to TV presenter Evan Davis about why we are willing to believe lies, no matter how outlandish

How to argue with a very emotional person, by Timandra Harkness: A handy guide to debating successfully in an age when people are shying away from it

Brain boxes, by Tess Woodcraft: A neuroscientist on why some people are willing to believe anything, even that their brains can be frozen

Identity’s trump cards, by Sarah Ditum: We’re damaging debate by saying only those with a certain identity have a right to an opinion on that identity

How to find answers to life’s questions, by Alom Shaha: A physics teacher on why a career-focused science approach isn’t good for students thinking outside the box

Not reading between the lines, by David Ulin: Books aren’t just informative, they offer a space for quiet reflection. What happens if we lose the art of reading?

Campaign lines, by Irene Caselli: Can other campaigners learn from Argentina’s same-sex marriage advocates how to win change?

Hungary’s unscientific swivel, by Dan Nolan: First they came for the humanities and now Hungary’s government is after the sciences

China’s deadly science lesson, by Jemimah Steinfeld: How an ill-conceived campaign against sparrows contributed to one of the worst famines in history

Inconvenient truths, by Michael Halpern: It’s a terrible time to be a scientist in the USA, or is it? Where there are attacks there’s also resistance

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Global View”][vc_column_text]

Beware those trying to fix “fake news”, by Jodie Ginsberg: If governments and corporations become the definers of “fake news” we are in deep trouble

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Cry freedom, by Rachael Jolley: An interview with Trevor Phillips on the dangers of reporters shying away from the whole story

When truth is hunted, by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: The award-winning Kenyan author on having his work hunted and why the hunters will never win

Return of Iraq’s silver screen, by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Iraq’s film industry is reviving after decades of conflict. Can it help the nation rebuild?

Book ends, by Alison Flood: Interviews with Olga Tokarczuk, Kamila Shamsie and Roberto Saviano about the best banned books

Pricing blogs off the screen, by Amanda Leigh Lichtenstein: The Tanzanian government is muzzling the nation’s bloggers through stratospheric fees

Modi’s strange relationship with the truth, Anuradha Sharma: The Indian prime minister only likes news that flatters him. Plus John Lloyd on why we should be more concerned about threats to Indian media than US media

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Word search, by Ian Rankin: The master of crime writing spins a chilling tale of a world in which books are obsolete, almost, in an Index short story exclusive

Windows on the world, by Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee: The British-Iranian mother and her fellow inmate on life inside Tehran’s notorious Evin prison. Plus poems written by both, published here for the first time

Metaphor queen, by Sheng Keyi: The Chinese writer on talking about China’s most sensitive subjects – and getting away with it, sort of. Also an exclusive extract from her latest book

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Column”][vc_column_text]

Index around the world, by Danyaal Yasin: A member of the new Index youth board from Pakistan discusses the challenges she faces as a journalist in her country

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Threats from China sent to UK homes, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Even outside Hong Kong, you’re not safe criticising Chinese-government rule there. We investigate threatening letters that have appeared in the UK

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The Autumn 2018 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with Academy of Ideas founder and director Claire Fox, Tanzanian blogger Elsie Eyakuze and Budapest-based journalist Dan Nolan.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The Autumn 2018 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with Academy of Ideas founder and director Claire Fox, Tanzanian blogger Elsie Eyakuze and Budapest-based journalist Dan Nolan.

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

31 Aug 2018 | China, Journalism Toolbox (Chinese), Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.01 Spring 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”中国政府最近新通过一项法律,该项法律将惩罚官方认为错误的历史叙述。林慕莲 为《失忆人民共和国—重返天安门》一书作者,她认为在当下的中国她将无法完成此书的写作。”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

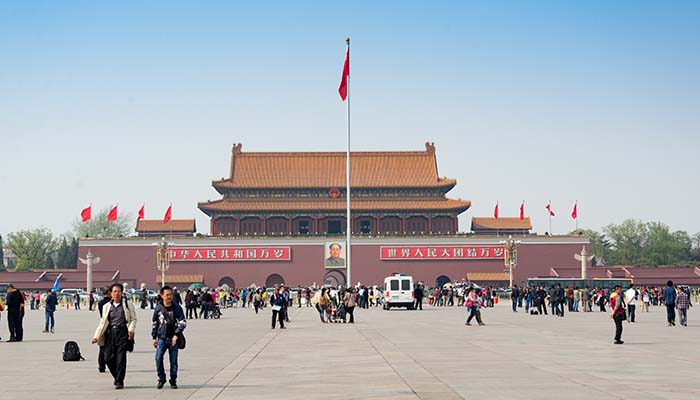

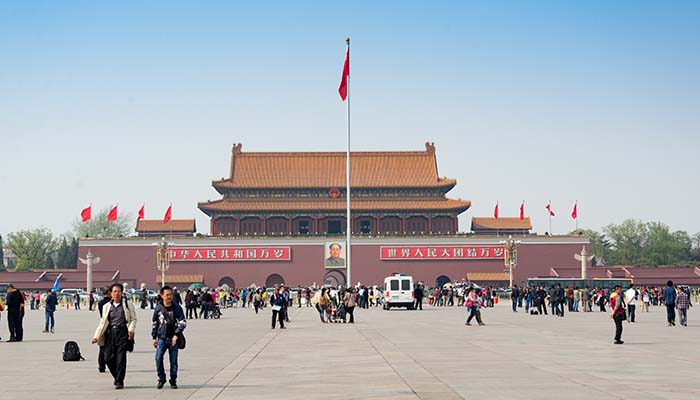

天安门广场, 2013 年. Credit: xiquinhosilva/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

在写作《失忆人民共和国—重返天安门》时,我在快餐厅度过了很长一段时光。我其实并不喜欢快餐食品,但是我所采访的异见人士都十分喜欢快餐厅,他们认为嘈杂的环境会使警方难以监控。当我和鲍彤在麦当劳餐厅交谈时,他能轻而易举地认出跟踪他的便衣警察。鲍彤先生因六四事件而遭受七年牢狱之灾,他也是六四后被判处徒刑的最高阶政府官员。天安门母亲运动是一群六四难属组成的民间组织。当我造访该组织创办人张先玲女士时,她第一句话便是:“他们知道你要来。”警察已经与张先玲通过电话并询问了我此行的目的。警察可能是通过窃听张女士或我的电话得知消息。对我们监控是明确设计好的,其目的就是恐吓和骚扰所有相关人员。

我当时是美国全国公众广播电台驻北京记者,因工作之便我有机会采访到这些受访者。然而我还是十分谨慎,甚至我的孩子在很长一段时间都不知道这本书的存在。整个写作过程我十分紧张,我用一台不能上网的电脑写作,写完后便将电脑锁在卧室的保险箱里。

这样的书在当今中国的大环境下我无法完成的。2013年我在北京的四所大学里对一百名大学生做了一项粗略的调查,我问他们是否能认出坦克人的照片。这是一张著名的六四事件照片,一名身着白色衬衫的年轻男子在北京长安街上阻挡向其驶来的坦克车队。在受访的一百名大学生中, 只有十五人知道这张照片的拍摄地点。一年后一个法国采访团队试图在北京进行类似的街访,然而街访开始不到十分钟警察便到达现场。事后该采访团队被警方审问长达六个小时。如今在中国很难找到愿与外国媒体交流任何话题的人,更不用说这种中国近代历史上最具政治敏感性的事件了。

在绰号为 “万能主席”(the Chairman of Everything, CEO)的习近平领导下,对历史事件的阐释也被其控制。他编织出“中国梦是一个关于历史,现在和未来的梦想”的口号,这一口号在时间上有无所不包的本质。 他认为“中华民族伟大复兴”的梦想取决于对历史的正确理解,而这种对历史的理解越来越需要通过强制的手段实施。为此,中国去年通过立法将“历史虚无主义”引入民法总则,以确保任何针对官方历史叙述的独立质疑都将受到惩处以及经济制裁。如今,“诋毁侮辱英雄和烈士的姓名、肖像、名誉和荣誉”是一项民事罪行。

在官方不断压制历史研究的背景下,21世纪的中国统治者正向秦始皇的道路继续前进。公元前213年秦始皇下令焚书,销毁官方版本以外的所有的历史记录。在这场对知识的彻底破坏运动中,甚至连秦始皇自己的族谱都被摧毁。正如司马迁在一百多年后评价秦始皇其目的是让百姓无知并确保没有人用历史来批评他。为了强化其统治,在公元前210年秦始皇下令埋葬了一群向他提出批评的儒家学者。

今天的坑儒的手段就是长期监禁。去年维权人士陈云飞因“寻衅滋事罪”被判处四年有期徒刑。他唯一的罪行是祭扫六四遇难者。将坦克人印上酒标的四名民主活动人士也因“煽动颠覆国家政权罪”将面临终身监禁。这样的审判表明六四事件随着时间的推移而变得更加敏感。

已故诺贝尔和平奖得主刘晓波《在亡灵目光的俯视下—六四十四周年祭》中写道“记忆,被精致的无耻言说所切割”:

压抑了太久,

但那秘密的预谋仍然禁闭在谎言的堂皇之中

多年来,阿里巴巴的马云和还未当选美国总统的唐纳德特朗普都声言同情中国政府的血腥镇压。与此同时北京当局在强化官方历史表述上取得巨大成功:事实上在1989年的镇压中四川成都同北京一样也有平民伤亡,然而成都的伤亡事件鲜有报道。我只是在为本书调研的过程中发现这一史实(此间笔者查阅了大量海外资料,这个过程十分艰辛)。中国国内对六四事件的描述存在着大量明显错误,大学教科书同样如此。

众所周知,中国政府的档案很难查阅,如今情况变得越发困难。最近哈佛大学历史学这宋怡明教授(Michael Szonyi)教授发布的一张照片,照片中显示在四川省档案馆有关1949年后的档案架,除了一个”开放目录“ 的牌子外,空空如也,什么都没有开放。胡佛研究所(Hoover Institution)研究员谭安(Glenn Tiffert)最近的研究表明,北京当局正在系统性地审查中国学术期刊,其目的是篡改对历史敏感事件的表述。历史资料的严重匮乏同被列入中国签证黑名单的恐惧意味着西方学者常常会回避像六四事件这样的敏感话题。

六四受害者如张先玲女士和鲍彤先生年事已高,我们有随时失去历史亲历者的危险。对六四的记忆存在于深锁的大门里,警察的高压警卫下,流亡社区的争吵中,尘土飞扬的大学图书馆书架上,— 至少现在— 还有每年在香港举办的六四烛光悼念晚会。我写这本书的目的是尽可能地填补其中的空白,虽不完美,但为时不晚。四年以后也许就来不及了。

六四事件很重要。中国领导人能发动国家政权机器来扼杀最微小的纪念活动。同时对史实无知也很重要。这种强迫无知也有其代价,借用一位参加我在美国大学演讲的一位中国留学生的话来总结:“我在中国生活了十八年,现在我意识到我对自己国家的历史一无所知。我上的是最好的学校,管理最严格的学校,然而我对任何事都是一无所知。”

本文最初发表于《审查指数》2018年春季刊 ,作为关于篡改历史的特别报道的一部分。点击这里查看更多信息

林慕莲是一位屡获殊荣的记者,曾任美国全国公众广播电台(NPR)及BBC驻华记者。著有《人民共和国失忆症–天安门再访》(2014年)

This is a translated version of an article that originally appeared in the 2018 spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine as part of a special report on the abuse of history. Click here for more information

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine produces regular podcasts in which we speak to some of the most interesting writers, thinkers and activists around the globe.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine produces regular podcasts in which we speak to some of the most interesting writers, thinkers and activists around the globe.

Click here to see what’s in our archive.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, Index on Censorship magazine explores the free speech issues from around the world today.

Themes for 2018 have included Trouble in Paradise, The Abuse of History and The Age of Unreason.

Explore recent issues here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Aug 2018 | News and features, Press Releases, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”96746″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is honoured to announce that our magazine has won an ‘Award of Excellence’ in the ‘Magazines, Journals & Tabloids – Writing (entire issue)’ category for the Awards for Publication Excellence (APEX). The award was given to our winter 2017 issue What price protest? How the right to assembly is under threat.

This is the second year Index on Censorship has won an APEX award. Last year Index won a Grand Award in the same category for our issue Truth in danger, danger in truth: Journalists under fire and under pressure.

APEX Awards are based on excellence in graphic design, editorial content and overall communications excellence. This year there were over 1,400 entries, with competition being “exceptionally intense”, the APEX site noted. “Each year, the quality of entries increases. Overall, this year’s entries displayed an exceptional level of quality,” it said.

“We are thrilled to have received this award for a second year in a row. As the winning issue highlighted, the right to protest is under threat throughout the globe. We hope awards like this will raise awareness of this important issue, while also acknowledging the excellent standard of journalism and writing, design and hard work that goes into producing the magazine,” Jemimah Steinfeld, deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine, said.

The protest issue, which came out at the end of 2017, considered the relevance of the 1968 protests 50 years on. It looked at the areas where the 1968 protests had been concentrated, such as Prague and Paris, and addressed what relevance these protests still have today. It also looked at the current state of protest across the globe. Particularly notable articles included one from the UK-based writer Sally Gimson about how central areas in English cities are being privatised and with that the right to protest is under threat, and an article from Wael Eskander, an Egyptian journalist, about witnessing the dangers and now demise of protest in his country over the past few years. There were also contributions from Micah White, one of the co-founders of the Occupy movement, and an interview with the husband of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who spoke about the importance of protest in relation to his wife’s imprisonment.

For more information on the protest issue click here. For more information on the APEX awards click here: http://apexawards.com/A2018_Win.List.pdf.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]ISSUE: VOLUME 46.04 WINTER 2017

What price protest?

How the right of assembly is under threat

The winter 2017 Index on Censorship magazine explores 1968 – the year the world took to the streets – to discover whether our rights to protest are endangered today.

Micah White proposes a novel way for protest to remain relevant. Author and journalist Robert McCrum revisits the Prague Spring to ask whether it is still remembered. Award-winning author Ariel Dorfman‘s new short story — Shakespeare, Cervantes and spies — has it all. Anuradha Roy writes that tired of being harassed and treated as second class citizens, Indian women are taking to the streets.

Editorial: Poor excuses for not protecting protest | Full contents | Podcast[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css=”.vc_custom_1491471988224{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column css=”.vc_custom_1474781640064{margin: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1477669782590{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;}”]CONTRIBUTORS[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css=”.vc_custom_1491471994875{margin-top: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781919494{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Ariel Dorfman” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”72266″]Ariel Dorfman is a playwright, author, essayist and human rights activist. His play Death and the Maiden won the 1992 Lawrence Olivier award and was adapted into a film.[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781952845{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Anuradha Roy” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”96805″]Anuradha Roy is an award-winning novelist, journalist and editor. She has written three novels, including Sleeping on Jupiter, which was long-listed for the Man Booker Prize.[/staff][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474781958364{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][staff name=”Micah White” color=”#ee3424″ profile_image=”96806″]Micah White is an activist, journalist and academic, who co-created Occupy Wall Street. He is author of The End of Protest: A New Playbook for Revolution, which was published in 2016.[/staff][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”top” css=”.vc_custom_1513939419504{margin-top: 30px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 30px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1505202277426{background-color: #455560 !important;}”][vc_column_text el_class=”text_white”]Editorial: Poor excuses for not protecting protest

Fifty years after 1968, the year of protests, increasing attacks on the right to assembly must be addressed, argues Rachael Jolley.

Sadly this basic right, the right to protest, is under threat in democracies, as well as, less surprisingly, in authoritarian states. Fifty years after 1968, a year of significant protests around the world, is a good moment to take stock of the ways the right to assembly is being eroded and why it is worth fighting for.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1477280180238{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1512406771641{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/magazine-winter2017-1500.jpg?id=96748) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}” el_class=”resp-0margin”][vc_column_inner css=”.vc_custom_1474716964379{margin: 0px !important;border-width: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;}”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1513939361978{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Contents

A look at what’s inside the winter 2017 issue, which explores the power of protest.

December 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720637924{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1513939407866{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Zaman_protest.jpg?id=81952) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1533801648458{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;}”]Magazine Extra: Podcast

Featuring interviews with authors in this issue.

December 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” css=”.vc_custom_1517585906327{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474716728107{margin: 0px !important;border-width: 0px !important;padding: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1517586137918{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/MG_3736.jpg?id=97797) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1517585967524{padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;}”]Magazine launch

A look at the magazine launch party for the winter 2017 issue #WhatPriceProtest

December 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720465330{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1517586176452{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/6MD4OKVXIG5JX3NEIA2M_prvw_63818.jpg?id=97558) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}” el_class=”resp-0margin”][vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1517586002603{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]Special focus: Book fairs and freedom

After Gothenburg and Frankfurt book fairs faced tension over who was allowed to attend, we asked four leading thinkers, Peter Englund, Ola Larsmo, Jean-Paul Marthoz, Tobias Voss, to debate the issue.

December 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1474720476661{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”image-content-grid”][vc_row_inner css=”.vc_custom_1517586191965{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-top-width: 0px !important;border-right-width: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 0px !important;border-left-width: 0px !important;padding-top: 65px !important;padding-right: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 65px !important;padding-left: 0px !important;background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/171110Index.jpg?id=97533) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column_inner][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text css=”.vc_custom_1517586030050{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;padding-top: 20px !important;padding-right: 20px !important;padding-bottom: 20px !important;padding-left: 20px !important;background-color: #78858d !important;}” el_class=”text_white”]China’s middle-class revolt

As China’s economy slows, an unexpected group has started to protest – the country’s middle class. Robert Foyle Hunwick reports on how effective they are

December 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1474815446506{margin-top: 30px !important;margin-right: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 30px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;background-color: #455560 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1478506027081{padding-top: 60px !important;padding-bottom: 60px !important;background: #455560 url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/magazine-banner2.png?id=80745) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1474721694680{margin-top: 0px !important;margin-bottom: 0px !important;padding-top: 0px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE TO

INDEX ON CENSORSHIP MAGAZINE” font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:24|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_column_text]Every subscription helps Index’s work around the world

SUBSCRIBE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

25 Jul 2018 | News and features, Tim Hetherington Fellowship

[vc_row full_height=”yes” content_placement=”middle” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1532521019562{background-color: #ffffff !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”78192″ img_size=”full”][vc_custom_heading text=”Kieran Etoria-King, the second Tim Hetherington fellow, speaks about his time as the editorial assistant, and the opportunities it’s given him” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:center|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“It made it on the front cover of the magazine so that was a big, proud moment,” said former Index editorial assistant Kieran Etoria-King, talking about his interview with stage star and model Lily Cole.

Etoria-King, now a graduate trainee at Channel 4, was the 2016/7 Tim Hetherington fellow at Index, a programme for journalism graduates from Liverpool John Moores University and backed by the Tim Hetherington Trust.

During his time as the second LJMU/Tim Hetherington fellow, Etoria-King worked on four issues of the magazine and on the website throughout the year, as well as interviewing Cole.

“My proudest moment editorially was the commissioning, when I got to the point where I felt like I was able to bring in ideas,” Etoria-King said. “I saw a picture of some North Korean art, and when I saw that I became fascinated by these amazing North Korean paintings I’d never seen before. I pitched that idea, and then went out and found someone, BG Muhn, who is an expert on the subject, and was able to write a really good piece about it. That was probably the first moment where I felt like, ‘yeah, I can contribute to this and able to bring stuff to the table’. It was like the first or second piece from the front in that issue so that was amazing.”

Etoria-King has taken the skills learned at Index into his new role. He said: “The confidence that I can bring ideas to the table has been a huge help.”

“Anywhere you go in the media, people are gonna be fascinated by the work Index does, even if they haven’t heard of it, when you tell them what it is, they’re gonna be fascinated.”

Talking about what he learned during his year on the editorial team, he said: “They really helped me really refine what to put in applications, refine my skills and how to pitch myself. You couldn’t really ask for a better introduction [to media], because you’ve got so much experience there in Sean, Rachael and Jemimah, Jodie and the whole organisation. Being such a small team you have a lot of input, and your presence is really valued and your input is really valued.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”94174″ img_size=”large” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Anywhere you go in the media, people are gonna be fascinated by the work Index does”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

The fellowship was set up in memory of Tim Hetherington, a photojournalist from Liverpool. He is best known for his work covering soldiers and conflicts including Afghanistan and Libya. His photography was celebrated for focusing on individuals’ experiences, not just the war zones.

Hetherington’s assignments took him from the UK to Africa where he lived and worked. He also studied US fighting forces for a year in Afghanistan from 2007 to 2008, which led to the Oscar-nominated film Restrepo and Infidel photo book. He also worked in Libya, where he sadly lost his life in 2011 from a mortar attack during the country’s civil war.

“Tim spent his whole life challenging limitations on expression,” said Stephen Mayes of the Tim Hetherington Trust, including a period of time spent as an investigator for the United Nations Security Council’s Liberia Sanctions Committee.

“The opportunity to introduce new talent to work in this vital field is unmissable and we wholeheartedly join with LJMU and Index to promote the values of free speech and political expression.”

The Tim Hetherington fellow works on the award-winning Index on Censorship magazine and website as the editorial assistant with opportunities to do a range of tasks including interviews and podcasts.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Danyaal Yasin is the 2017/18 Tim Hetherington fellow at Index

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The Autumn 2018 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with Academy of Ideas founder and director Claire Fox, Tanzanian blogger Elsie Eyakuze and Budapest-based journalist Dan Nolan.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”102479″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The Autumn 2018 magazine podcast, featuring interviews with Academy of Ideas founder and director Claire Fox, Tanzanian blogger Elsie Eyakuze and Budapest-based journalist Dan Nolan.