17 Apr 2018 | Index in the Press

Each year Index on Censorship honours activists who have been at the forefront of tackling censorship globally. Click hears from Jodie Ginsberg about some of nominees including creators of the Museum of Dissidence in Cuba. She is joined Guy Muyembe, from Habari RDC (a collective of young Congolese bloggers), to discuss digital activism. Listen to the full podcast

10 Apr 2018 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.01 Spring 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

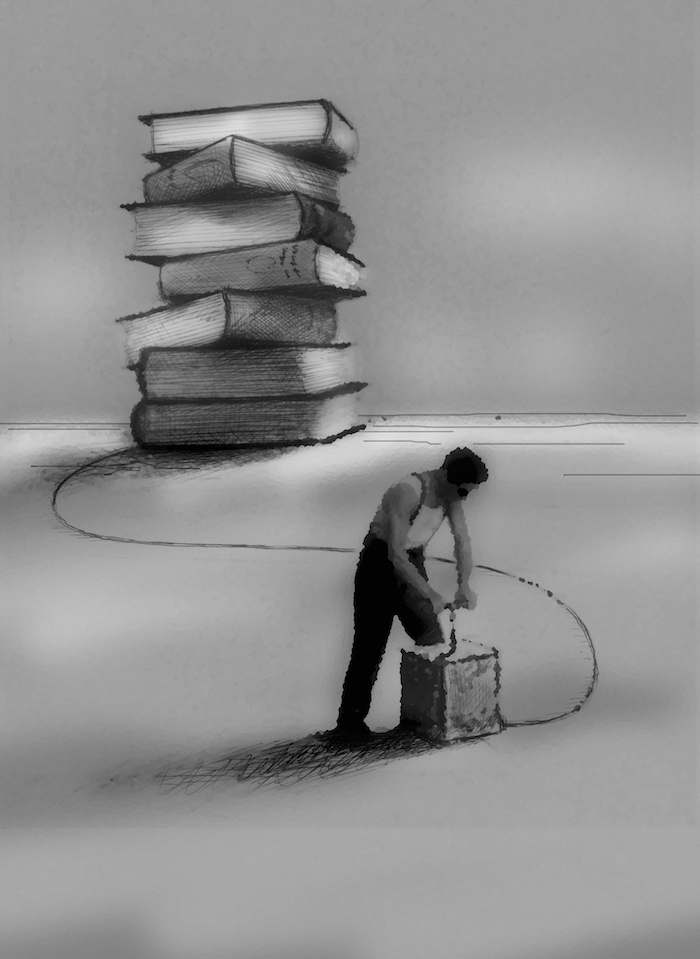

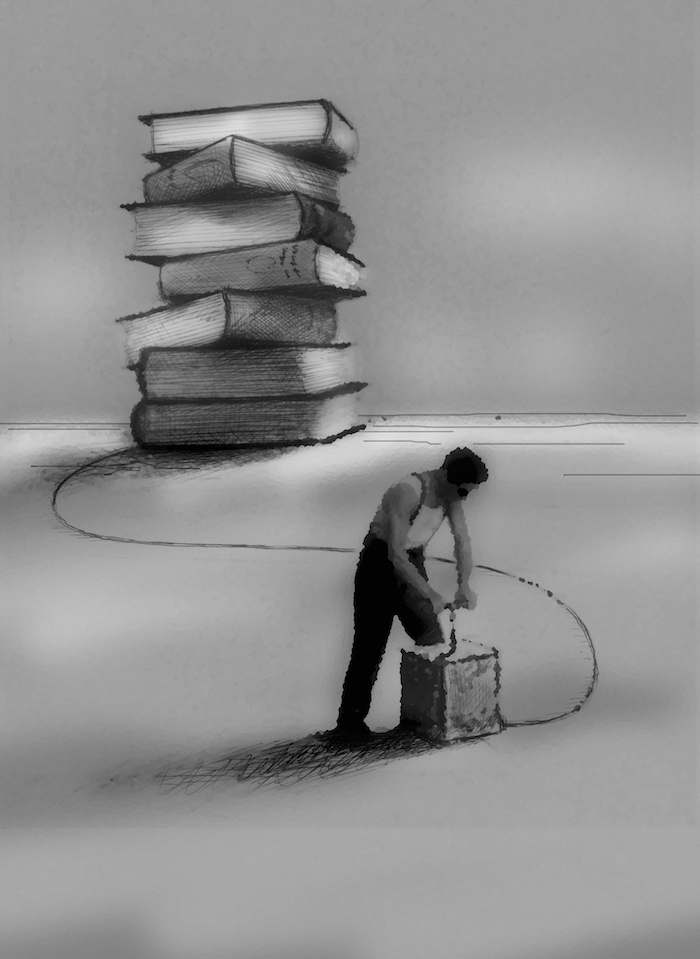

Authoritarian leaders know their history. They also know the history they would like you to know. They are aware, perhaps more than anyone else, that choosing images and stories from the past to align and amplify the ways a country is run can be a terribly powerful tool.

As Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan discussed with Index for this issue, dictators have been aware of the power of history to make their arguments for centuries. From the first Chinese emperors to today’s leaders – China’s Xi Jinping and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, among others – the selection of historical stories which reflect their view of the world is revealing.

“The thing about history is if people know only one version then it seems to validate the people in power,” said MacMillan.

But if you know more, you can use that information to make informed decisions about what worked in the past – and what didn’t – allowing people to learn and move on.

And right now, historical validation is an active part of the political playbook. In Russia, Vladimir Putin is a big fan of the tale of the great and powerful Russia. And what he doesn’t like are people who don’t sign up to his version of history.

Even asking questions about the past can provoke anger at the top. It interferes with the control, you see.

In 2014, Dozhd TV had an audience poll about whether Leningrad should have surrendered to the Nazis during World War II. Immediately there were complaints, as Index reported at the time. The station changed the wording of the question almost immediately, but within months various cable and satellite companies had dropped Dozhd from their schedules. Question and you shall be pushed out into the cold.

From the start, this magazine has covered how different countries have attempted to control the historical knowledge their citizens receive by limiting the pipeline (rewriting textbooks or taking history off the syllabus completely, for instance); using social pressure to make certain views taboo; and, in extreme cases, locking up historians or making them too afraid to teach the facts.

In our Winter 2015 issue, we covered the story of a Palestinian teacher who took his students to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland because he felt they should know about the Holocaust. But not everyone agreed. While he was on the trip, there were demonstrations against him, his office was stormed and his car was torched. Later there were threats against his family. To escape the danger, he and his family had to move abroad. The teacher, Mohammed Dajani Daoudi, who wrote about his experiences for the magazine, said: “My duty as a teacher is to teach – to open new horizons for my students, to guide them out of the cave of misconceptions and see the facts, to break walls of silence, to demolish fences of taboos.”

What an incredibly brave vision for a teacher to have in the face of a mob of people who would seek to damage his life, and that of his family, to show how much they disapproved of what he was trying to do.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”But censoring history is not the only way to go about establishing inaccuracies and ill-informed attitudes about the past. Another option is to spin it.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Dajani Daoudi is not alone in fighting against the odds to bring research, open thinking and a wide base of knowledge to students. But, as our Spring 2018 issue shows, the odds are starting to stack up against people like him in an increasing number of places.

In 2010, Maureen Freely wrote a piece called Secret Histories for this magazine, about Turkish laws that had kept most of its citizens in the dark about the killings of a million Armenians in the last years of the Ottoman empire, and how those laws were enforced by making certain things – including criticising the legacy of modern Turkey’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – illegal.

Turkey’s government today has just passed a law making mention of the word “genocide” an offence in parliament, as our Turkish correspondent, Kaya Genç, reports on page 22.

But censoring history is not the only way to go about establishing inaccuracies and ill-informed attitudes about the past. Another option is to spin it.

Resisting Ill Democracies in Europe, the excellent report from the Human Rights House Network, acknowledges that a common thread in countries where democracy is weakening is the “reshaping of the historical narrative taught in schools”. In Poland, the introduction of a Holocaust law means possible imprisonment for anyone who suggests Polish involvement in the Holocaust or that the concentration camps were Polish. In Hungary, the rhetoric of the ruling party is to water down involvement of its citizens in the Holocaust and to rehabilitate the reputation of former head of state Miklós Horthy.

At the same time as undermining public trust in the media, governments in this spin cycle seek to stigmatise academics, as well as close down places where open or vigorous debate might take place. The result is often the creation of a “them and us” mentality, where belief in the avowed historical take is a choice of being patriotic or not.

As the HRHN report suggests, “space for critical thinking, independent research and reporting and access to objective and accurate information are pre-requisites for informed participation in pluralistic and diverse societies” and to “debunk myths”.

However, if your objective is not having your myths debunked then closing down discussions and discrediting opposition voices is the ideal way to make sure the maximum number of people believe the stories you are telling.

That’s why historians, like journalists, are often on the sharp end of a populist leader’s attack. Creating a nostalgia for a time where supposedly the garden was rosy and citizens were happy beyond belief often forms another part of the political playbook, alongside creating a false history.

Another tactic is to foster a sense that the present is difficult and dangerous because of change and because of threats to “traditional” values; and a sense that history shows a country as greater than it is today. The next step is to find a handy enemy (migrants and LGBT people are often targets) to blame for that change and to stoke up anger.

Access to the past matters. Knowledge of what happened, the ability to question the version you are receiving, and probing and prodding at the whys and wherefores are essentials in keeping society and the powerful on their toes.

In this issue of Index on Censorship magazine, we carry a special report about how history is being abused. It includes interviews with some of the world’s leading historians – Lucy Worsley, Margaret MacMillan, Charles van Onselen, Neil Oliver and Ed Keazor (p31).

We look at how history is being reintroduced into schools in Colombia (p60) and how efforts continue to recognise the victims of General Franco’s dictatorship in Spain (p72). We also ask Hannah Leung and Matthew Hernon to talk to young people in China and Japan to discover what they learned at school about the contentious Nanjing massacre. Find out what happened on page 38.

Omar Mohammed, aka Mosul Eye, writes on page 47 about his mission to retain information about Iraq’s history, despite risk to his life, while Isis set out to destroy historical icons.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor of Index on Censorship. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on The Abuse of History.

Index on Censorship’s spring 2018 issue, The Abuse of History, focuses on how history is being manipulated or censored by governments and other powers.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89164″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229108535157″][vc_custom_heading text=”Brave new words” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229108535157|||”][vc_column_text]2010

In 2010, Maureen Freely wrote a piece called Secret Histories for this magazine, about Turkish laws that had kept most of its citizens in the dark about the killings of a million Armenians in the last years of the Ottoman empire[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90649″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220008536796″][vc_custom_heading text=”Censorship in China” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013495334|||”][vc_column_text]September 2000

How China attempts to censor, using different methods[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”71995″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229308535477″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taboos” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422013513103|||”][vc_column_text]Winter 2015

We tell the story of a Palestinian teacher who took his students to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland because he felt they should know about the Holocaust. But not everyone agreed.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The abuse of history” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F04%2Fthe-abuse-of-history%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how governments and other powers across the globe are manipulating history for their own ends

With: Simon Callow, David Anderson, Omar Mohammed [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/04/the-abuse-of-history/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Jan 2018 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Yesterday marked three months since the murder of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Gathering outside the Maltese embassy in Malta House, London, members from Index on Censorship stood with seven other free speech and criminal justice organisations to mark the anniversary and call on the Maltese government to ensure justice is served. I spoke with Hannah Machlin, project manager for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform, Cat Lucas, programme manager for English Pen’s Writers at Risk programme, and Rebecca Vincent, UK bureau director for Reporters Without Borders for this special podcast.

During the vigil, participants left bay leaves — which in Greek mythology are a sign of bravery and strength — outside the embassy in a sign of solidarity with supporters in Malta, while a statement from Caruana Galizia’s family was read out.

Caruana Galizia was killed on 16 October 2017 when a bomb placed under her car exploded as she was leaving her home in Bidnija, Malta. Sixteen days prior to the fatal attack, Caruana Galizia filed a police report saying she was being threatened.

Through her investigative journalism career, Caruana Galizia exposed corrupt politicians and other officials, uncovering a number of corruption scandals in the Panama Papers. Caruana Galizia also investigated links between Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat to secret offshore bank accounts, to allegedly hide payments from Azerbaijan’s ruling family. Her work on government corruption also led to early elections in Malta in June 2017.

At the time of her death, Caruana Galizia was subject to several libel suits and counts of harassment. Her assets were frozen in February 2017 following a request filed by Economic Minister Chris Cardona and his EU presidency policy officer Joseph Gerada.

Her murder was condemned by many from the international community, with a previous vigil held on the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists, where nearly 60 free expression advocates gathered, calling for justice and an open and transparent investigation into her death.

Malta is currently ranked 47th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ 2017 World Press Freedom Index, and 47th out of 176 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index 2016.

Seven reports of violations of press freedom were verified in Malta in 2017, according to Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project. Five of those are linked to Caruana Galizia and her family.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1516205516926-5b43be63-70a3-7″ taxonomies=”18782″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Jan 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Previo a publicación de un nuevo informe sobre las amenazas a los medios de comunicación en el país, Rhodri Davies habla con los sirios que crearon su propia emisora de radio”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Varios locutores de la emisora SouriaLi, reunidos con invitados en Amán (Jordania), SouriLa

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

«Compramos unos trapos muy gruesos para fabricar una especie de insonorización; así nuestras voces no se oirían desde fuera y el sonido de las bombas no entraría al apartamento», cuenta el periodista Dima Kalayi, describiendo cómo un grupo de personas unió sus fuerzas en un piso diminuto y comenzó a realizar programas para una emisora independiente siria. El piso de Damasco fue el primer lugar en el que pudieron reunir a gran parte del equipo de la nueva emisora.

«Queríamos que SouriaLi fuera un ejemplo de cómo nos gustaría que [fuera] Siria en el futuro», dice Caroline Ayub, una de los cuatro cofundadores de la emisora, que ayudó a montarlo todo desde el exilio. Ayub explica que querían mostrar la identidad diversa de Siria, al mismo tiempo que recordaban también la cultura que todos tienen en común. Por otro lado, les daba la sensación de que se recurría demasiado a los medios internacionales para informarse sobre su propio país.

«Para nosotros, el objetivo principal de la revolución era expresar la propia voz e identidad. Y para ello es esencial hacer que esa voz continúe», añade Ayub, que huyó a Marsella tras haber estado presa durante un mes en 2012 por distribuir huevos de Pascua con citas sacadas de la Biblia, junto a otras del Corán (las autoridades la acusaron de terrorismo).

SouriaLi, que puede traducirse como «Siria es mía», transmite las 24 horas y cuenta con podcasts, contenido visual y una app. Sin embargo, no compite contra los programas de noticias duras a tiempo real. La intención de la emisora es reflejar los problemas que sufre el país por medio de debates y tertulias —interactuando en vivo con el público por WhatsApp y Skype regularmente—, así como radionovelas y cuentacuentos.

Lo suyo es verdadera vocación. El informe del Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas, cuya publicación está prevista para noviembre, hará mención a la creciente gravedad de la situación de los periodistas sirios y espera que el país pase de estar en tercer lugar a ser la segunda nación más peligrosa en su índice global.

SouriaLi se vale de periodistas para recabar información, que luego contrasta con otras fuentes. Al contar con miembros provenientes de una amplia área geográfica dentro del país —aunque la mayoría viven ahora en el exilio—, su red de contactos en Siria es “extensa”, según Iyad Kalas, otro cofundador y director de programación. Explica que siempre examinan la procedencia de las fuentes y el modo en el que se ha obtenido la información para poder establecer su nivel de credibilidad.

Su serie semanal titulada Yadayel (“Trenzas”) cuenta historias de mujeres, como el trato que reciben en puestos de control, la experiencia de vivir en Raqa bajo el control del EI o cómo es trabajar en un hospital.

«Es muy importante para nosotras, porque así estás dándoles voz [a] las mujeres. La mayoría de estas mujeres provienen de una sociedad muy oprimida y conservadora», explica Ayub.

Llegó a haber 11 personas de la emisora en Siria, más las que trabajaban desde fuera. Hoy, sin embargo, solo queda un miembro del equipo en el país: muchos de ellos acabaron en la cárcel antes de marcharse de Siria, algunos por oponerse al gobierno y otros por enviar ayuda. La mayoría de los que no fueron arrestados, como Kalayi, que vive en Berlín desde 2013, abandonaron el país. Ayub describe SouriaLi como «un medio exiliado porque, por el momento, estamos en el exilio».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

El equipo ahora suma 27 miembros, voluntarios incluidos, que trabajan desde 14 países distintos de Oriente Medio, Europa y Norteamérica.

La labor de reafirmar la diversidad de Siria supone facilitar el acceso a las ondas a todas las voces del grupo, ya sean kurdas, suníes, chiíes, alauíes, armenias, cristianas o de otro tipo. Kalayi produjo una serie titulada Fatush, en la que tomaba recetas típicas de las diferentes regiones y grupos de Siria y hablaba sobre identidad étnica y problemas a menudo ignorados, mano a mano con la gastronomía.

SouriaLi trata de incluir una variedad de perspectivas, aunque las figuras prorrégimen raras veces aceptan la invitación. Pese a todo, la emisora ofrece la oportunidad de expresarse a todos los puntos de vista. «Creemos firmemente que los medios de comunicación, como una emisora de radio, una plataforma, deberían ser para todos los sirios», afirma Ayub.

Sus emisiones atraen a un público numeroso: tienen más de 450.000 seguidores en Facebook. La emisora solía emitir en FM en 12 zonas de Siria, en las que compañeros locales se encargaban de la transmisión. Sin embargo, el régimen de Assad siempre prohibía la emisión en las regiones que caían bajo su dominio, y diferentes grupos de combate de la oposición, como Yabhat al Nusra (entonces vinculado con Al Qaeda, hoy rebautizado como Yabhat Fateh al Sham), han tratado de controlar el contenido de SouriaLi. Exigían, por ejemplo, que dejasen de emitir ciertos programas y música, como el contenido kurdo, o los obligaban a emitir el Corán. La emisora también recibió amenazas del Estado Islámico.

SouriaLi se negó a recibir órdenes del gobierno o de sus oponentes, y puso fin a su transmisión en FM a mediados de 2016. «Así que decidimos dejarlo», relata Ayub. «Dijimos: “Siria ya no es [solo] Siria de la frontera adentro. Siria es todos los sirios de cualquier lugar.” Tenemos millones de sirios fuera, en Europa. Todos necesitan la esperanza, la información que estamos emitiendo, así que recalibramos nuestro centro atención».

La emisora de radio pasó a ser solo en línea. Su página web está disponible para la población siria, tanto en los lugares donde no hay censura como a través de VPN. También hay una versión pensada para evitar la censura que solo incluye la emisión de radio en directo.

Kalas, que abandonó Siria por Francia en 2012, cuenta que ahora la emisora podría pasar a estar solo en internet, pues «Siria es un país virtual» con oyentes repartidos por todos los puntos del globo. SouriaLi calcula que alrededor del 40% de su audiencia online está ubicada en Siria, otro 40% lo forma su diáspora y otro 18% son oyentes de habla árabe, principalmente de Irak y Egipto.

Mantener la moral alta es uno de los mayores retos a los que se enfrenta el equipo, según Kalas y Ayub. «Antes de 2011 no había realmente “medios” o “periodismo” en Siria», apunta Kalayi. Ahora, se siente optimista. «Tengo libertad para elegir los temas, cómo tratarlos, cómo presentarlos. Y esto es algo muy importante para mí como persona y como periodista». Y cuando las condiciones lo permitan, quiere volver a Siria y seguir haciendo eso mismo.

Ayub añade: «Yo creo que a un país [como] Siria le hacen falta miles y miles de proyectos de comunicación, muchas plataformas para que la gente se exprese, para debatir. Porque, sin debate, sin libertad de expresión, nunca existirá un país libre. Y esto, por supuesto, es aplicable a Siria también».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rhodri Davies es periodista independiente. Ha escrito reportajes desde Catar, Egipto, Irak y Yemen.

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista Index on Censorship en otoño de 2017.

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]