6 May 2022 | News and features, Pakistan, Syria, United Arab Emirates

Syria has become the latest country to implement new far-reaching cybercrime legislation that goes beyond what is necessary to keep the internet safe.

On 18 April, Syrian president Bashir al-Assad announced new laws that could result in harsh penalties criticising or otherwise embarrassing the Syrian government.

Anyone breaking the law can be jailed for up to 15 years and face penalties up to S£15 million (£23,000).

The highest fines and sentences are reserved for “crimes against the Constitution” and for undermining the prestige of the State including websites or content “aiming or calling for changing the constitution by illegal means, or excluding part of the Syrian land from the sovereignty of the state, or provoking armed rebellion against the existing authorities under the constitution or preventing them from exercising their functions derived from the constitution, or overthrowing or changing the system of government in the state”.

Publishing what the new law describes as “fake news…that undermines the prestige of the state or prejudices national unity” can lead to five-year jail sentences and S£10 million (£15,300) fines which seems to target bloggers and digital activists who publish criticism of the government online.

In a statement the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR) said the law could be used to violate many of the basic digital rights of citizens, especially freedom of expression and freedom of digital privacy.

It said, “GCHR believes that the law should be reviewed and its definitions defined more clearly to ensure the existence of a strong and practical law that does not violate the basic rights of citizens, but rather contributes to creating a free and accessible internet in which diverse opinions are respected and human rights are protected and promoted.”

The new law also obliges internet service providers to save internet data for all users for a period of time to be determined by the competent authorities.

The GCHR calls this “a flagrant violation of the digital privacy of citizens and provides ease of access by security services to all information related to peaceful online activists”.

The Syrian cybercrime law is just the latest in a growing body of legislation around the world ostensibly used to target cybercrime but clearly intended to stifle legitimate criticism and restrict freedom of expression.

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 81% of countries have now implemented cybercrime legislation with a further 7% with draft legislation.

Many argue that cybercrime legislation makes the internet a safer place but many countries with human rights are under attack, including Brazil, Myanmar and the UAE, are using such legislation to silence critics.

In January, the United Arab Emirates adopted new legislation that promised fines of up to AED100,000 and jail terms of up to a year for “anyone who uses the internet to publish, circulate or spread false news, rumours or misleading information, contrary to the news published by official sources”. These penalties are doubled when publication happens “during times of pandemic, crises or disasters”

Attempts to introduce such draconian legislation are being resisted by human rights and journalism associations.

In February this year, the Pakistani government passed an ordinance amending the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act, 2016. Of particular concern was an expansion of the “offences against dignity” section of the legislation to cover the publication of “false” information about organisations, companies and institutions, including the government and military.

However, in April, the Islamabad High Court, following challenges by the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists and the Pakistan Broadcasters Association, threw out the ordinance. The court noted: “Freedom of expression is a fundamental right and it reinforces all other rights guaranteed under the Constitution … [and] free speech protected under Article 19 and the right to receive information under Article 19-A of the Constitution are essential for development, progress and prosperity of a society and suppression thereof is unconstitutional and contrary to the democratic values.”

14 Apr 2022 | News and features, Russia, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022 Extras

The story of Index on Censorship is steeped in the romance and myth of the Cold War.

In one version of the narrative, it is a tale that brings together courageous young dissidents battling a totalitarian regime and liberal Western intellectuals desperate to help – both groups united in their respect for enlightenment values.

In another, it is just one colourful episode in a fight to the death between two superpower ideologies, where the world of letters found itself at the centre of a propaganda war.

Both versions are true.

It is undeniably the case that Index was founded during the Cold War by a group of intellectuals blooded in cultural diplomacy. Western governments (and intelligence services) were keen to demonstrate that the life of the mind could truly flourish only where Western values of democracy and free speech held sway.

But in all the words written over the years about how Index came to be, it is important not to forget the people at the heart of it all: the dissidents themselves, living the daily reality of censorship, repression and potential death.

The story really began not in 1972, with the first publication of this magazine, but with a letter to The Times and the French paper Le Monde on 13 January 1968. This Appeal to World Public Opinion was signed by Larisa Bogoraz Daniel, a veteran dissident, and Pavel Litvinov, a young physics teacher who had been drawn into the fragile opposition movement during the celebrated show-trial of intellectuals Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel (Larisa’s husband) in February 1966. This is now generally accepted as being the beginning of the modern Soviet dissident movement.

The letter itself was written in response to the Trial of Four in January 1968, which saw two students, Yuri Galanskov and Alexander Ginzburg, sentenced to five years’ hard labour for the production of anti-communist literature.

The other two defendants were Alexey Dobrovolsky, who pleaded guilty and co-operated with the prosecution, and a typist, Vera Lashkova.

Ginzburg later became a prominent dissident and lived in exile in Paris, Galanskov died in a labour camp in 1972 and Dobrovolsky was sent to a psychiatric hospital. Lashkova’s fate is unclear.

The letter was the first of its kind, appealing to the Soviet people and the outside world rather than directly to the authorities. “We appeal to everyone in whom conscience is alive and who has sufficient courage… Citizens of our country, this trial is a stain on the honour of our state and on the conscience of every one of us.”

The letter went on to evoke the shadow of Joseph Stalin’s show-trials in the 1930s and ended: “We pass this appeal to the Western progressive press and ask for it to be published and broadcast by radio as soon as possible – we are not sending this request to Soviet newspapers because that is hopeless.”

The trial took place in a courthouse packed with Kremlin supporters, while protesters outside endured temperatures of 50 degrees below zero.

The poet Stephen Spender responded to the letter by organising a telegram of support from 16 prominent artists and intellectuals, including philosopher Bertrand Russell, poet WH Auden, composer Igor Stravinsky and novelists JB Priestley and Mary McCarthy.

It took eight months for Litvinov to respond, as he had heard the words of support only on the radio and was waiting for the official telegram to arrive. It never did.

On 8 August 1968, the young dissident outlined a bold plan for support in the West for what he called “the democratic movement in the USSR”. He proposed a committee made up of “universally respected progressive writers, scholars, artists and public personalities” to be taken not just from the USA and western Europe but also from Latin America, Asia, Africa and, ultimately, from the Soviet bloc itself. Litvinov later wrote an account in Index explaining how he had typed the letter and given it to Dutch journalist and human rights activist Karel van Het Reve, who smuggled it out of the country to Amsterdam the next day. Two weeks later, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring.

On 25 August 1968, Litvinov and Bogoraz Daniel joined six others in Red Square to demonstrate against the invasion. It was an extraordinary act of courage. They sat down and unfurled homemade banners with slogans that included “We are Losing Our Friends”, “Long Live a Free and Independent Czechoslovakia”, “Shame on Occupiers!” and “For Your Freedom and Ours”.

The activists were immediately arrested and most received sentences of prison or exile, while two were sent to psychiatric hospitals.

Vaclav Havel, the dissident playwright and first president of the Czech Republic, later said in a Novaya Gazeta article: “For the citizens of Czechoslovakia, these people became the conscience of the Soviet Union, whose leadership without hesitation undertook a despicable military attack on a sovereign state and ally.”

When Ginzburg died in 2002, novelist Zinovy Zinik used his Guardian obituary to sound a note of caution. Ginzburg, he wrote, was “a nostalgic figure of modern times, part of the Western myth of the Russia of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, when literature, the word, played a crucial part in political change”.

Speaking 20 years later, Zinik told Index he did not even like the English word “dissident”, which failed to capture the true complexity of the opposition to the Soviet regime. “The Russian word used before ‘dissidents’ invaded the language was ‘inakomyslyashchiye’ – it is an archaic word but was adopted into conversational vocabulary. The correct translation would be ‘holders of heterodox views’.”

It’s perhaps understandable that the archaic Russian word didn’t catch on, but his point is instructive.

As Zinik warned, it is all too easy to romanticise this era and see it through a Western lens. The Appeal to World Public Opinion was not important because it led to the founding of Index. The letter was important because it internationalised the struggle of the Soviet dissident movement.

As Litvinov later wrote in Index: “Only a few people understood at the time that these individual protests were becoming a part of a movement which the Soviet authorities would never be able to eradicate.” Index was a consequence of Litvinov’s appeal; it was not the point of the exercise and there was no mention of a magazine in the early correspondence.

The original idea was to set up an organisation, Writers and Scholars International, to give support to the dissidents. It was only with the appointment of Michael Scammell in 1971 that the idea emerged to establish a magazine to publish and promote the work of dissidents around the world.

Spender and his great friend and co-collaborator, the Oxford philosopher Stuart Hampshire, were still reeling from revelations about CIA funding of their previous magazine, Encounter.

“I knew that [they]… had attempted unsuccessfully to start a new magazine and I felt that they would support something in the publishing line,” Scammell wrote in Index in 1981.

Speaking recently from his home in New York, Scammell told me: “I understood Pavel Litvinov’s leanings here. He understood that a magazine that was impartial would stand a better chance of making an impression in the Soviet Union than if it could just be waved away as another CIA project.”

Philip Spender, the poet’s nephew, who worked for many years at Index, agreed: “Pavel Litvinov was the seed from which Index grew… He always said it shouldn’t be anti-communist or anti-Soviet. The point wasn’t this or that ideology. Index was never pro any ideology.”

It has been suggested that Index did not mark quite such a clean break – it was set up by the same Cold Warriors and susceptible to the same CIA influence. In her exhaustive examination of the cultural Cold War, Who Paid the Piper, journalist Frances Stonor Saunders claimed Index was set up with a “substantial grant” from the Ford Foundation, which had long been linked to the CIA.

In fact, the Ford funding came later, but it lasted for two decades and raises serious questions about what its backers thought Index was for.

Scammell now recognises that the CIA was playing a sophisticated game at the time. “On one level this is probably heresy to say so, but one must applaud the skills of the CIA. I mean, they had that money all over the place. So, I would get the Ford Foundation grant, let’s say, and it never ever occurred to me that that money itself might have come from the CIA.”

He added: “I would not have taken any money that was labelled CIA, but I think they were incredibly smart.”

By the time the magazine appeared in spring 1972, it had come a long way from its origins in the Soviet opposition movement. It did reproduce two short works by Alexander Solzhenitsyn and poetry by dissident Natalya Gorbanevskaya (a participant in the 1968 Red Square demonstration, who had been released from a psychiatric hospital in February of that year). But it also contained pieces about Bangladesh, Brazil, Greece, Portugal and Yugoslavia.

Philip Spender said it was important to understand the context of the times: “There was a lot of repression in the world in the early ’70s. There was the imprisonment of writers in the Soviet Union, but also Greece, Spain and Portugal. There was also apartheid. There was a coup in Chile in 1973, which rounded up dissidents. Brazil was not a friendly place.”

He said Index thought of itself as the literary version of Amnesty International. “It wasn’t a political stance, it was a non-political stance against the use of force.”

The first edition of the magazine opened with an essay by Stephen Spender, With Concern for Those Not Free. He asked each reader of the article to say to themselves: “If a writer whose works are banned wishes to be published and if I am in a position to help him to be published, then to refuse to give help is for me to support censorship.”

He ended the essay in the hope that Index would act as part of an answer to the appeal “from those who are censored, banned or imprisoned to consider their case as our own”.

Since Index was founded, the Berlin Wall has fallen and apartheid has been dismantled. We have witnessed the “war on terror”, the rise of Russian president Vladimir Putin and the emergence of China as a world superpower.

And yet, if it is not too grand or presumptuous, the role of the magazine remains unchanged – to consider the case of the dissident writer as our own.

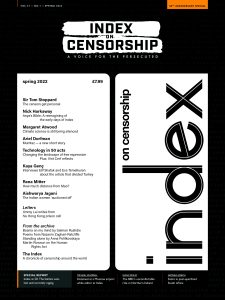

17 Mar 2022 | 50 years of Index, Afghanistan, Africa, Americas, Asia and Pacific, Bosnia, Brazil, China, Greece, Hong Kong, India, Iran, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Mexico, Nigeria, Northern Ireland, Philippines, Russia, Rwanda, South Africa, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States, Volume 51.01 Spring 2022 Extras

The spring issue of Index magazine is special. We are celebrating 50 years of history and to such a milestone we’ve decided to look back at the thorny path that brought us here.

Editors from our five decades of life have accepted our invitation to think over their time at Index, while we’ve chosen pieces from important moments that truly tell our diverse and abundant trajectory.

Susan McKay has revisited an article about the contentious role of the BBC in Northern Ireland published in our first issue, and compares it to today’s reality.

Martin Bright does a brilliant job and reveals fascinating details on Index origin story, which you shouldn’t miss.

Index at 50, by Jemimah Steinfeld: How Index has lived up to Stephen Spender’s founding manifesto over five decades of the magazine.

The Index: Free expression around the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern.

“Special report: Index on Censorship at 50”][vc_column_text]Dissidents, spies and the lies that came in from the cold, by Martin Bright: The story of Index’s origins is caught up in the Cold War – and as exciting

Sound and fury at BBC ‘bias’, by Susan McKay: The way Northern Ireland is reported continues to divide, 50 years on.

How do you find 50 years of censorship, by Htein Lin: The distinguished artist from Myanmar paints a canvas exclusively for our anniversary.

Humpty Dumpty has maybe had the last word, by Sir Tom Stoppard: Identity politics has thrown up a new phenonemon, an intolerance between individuals.

The article that tore Turkey apart, by Kaya Genç: Elif Shafak and Ece Temulkuran reflect on an Index article that the nation.

Of course it’s not appropriate – it’s satire, by Natasha Joseph: The Dame Edna of South Africa on beating apartheid’s censors.

The staged suicided that haunts Brazil, by Guilherme Osinski: Vladimir Herzog was murdered in 1975. Years on his family await answers – and an apology.

Greece haunted by spectre of the past, by Tony Rigopoulos: Decades after the colonels, Greece’s media is under attack.

Ugandans still wait for life to turn sweet, by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Hopes were high after Idi Amin. Then came Museveni …People in Kampala talk about their

problems with the regime.

How much distance from Mao? By Rana Mitter: The Cultural Revolution ended; censorship did not.

Climate science is still being silenced, by Margaret Atwood: The acclaimed writer on the fiercest free speech battle of the day.

God’s gift to who? By Charlie Smith: A 2006 prediction that the internet would change China for the better has come to pass.

50 tech milestones of the past 50 years, by Mark Frary: Expert voices and a long-view of the innovations that changed the free speech landscape.

Censoring the net is not the answer, but… By Vint Cerf: One of the godfathers of the internet reflects on what went right and what went wrong.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Five decades in review”][vc_column_text]An arresting start, by Michael Scammell: The first editor of Index recounts being detained in Moscow.

The clockwork show: Under the Greek colonels, being out of jail didn’t mean being free.

Two letters, by Kurt Vonnegut: His books were banned and burned.

Winning friends, making enemies, influencing people, by Philip Spender: Index found its stride in the 1980s. Governments took note.

The nurse and the poet, by Karel Kyncl: An English nurse and the first Czech ‘non-person’.

Tuning in to revolution, by Jane McIntosh: In revolutionary Latin America, radio set the rules.

‘Animal can’t dash me human rights’, by Fela Kuti: Why the king of Afrobeat scared Nigeria’s regime.

Why should music be censorable, by Yehudi Menuhin: The violinist laid down his own rules – about muzak.

The snake sheds its skin, by Judith Vidal-Hall: A post-USSR world order didn’t bring desired freedoms.

Close-up of death, by Slavenka Drakulic: We said ‘never again’ but didn’t live up to it in Bosnia. Instead we just filmed it.

Bosnia on my mind, by Salman Rushdie: Did the world look away because it was Muslims?

Laughing in Rwanda, by François Vinsot: After the genocide, laughter was the tonic.

The fatwa made publishers lose their nerve, by Jo Glanville: Long after the Rushdie aff air, Index’s editor felt the pinch.

Standing alone, by Anna Politkovskaya: Chechnya by the fearless journalist later murdered.

Fortress America, by Rubén Martínez: A report from the Mexican border in a post 9/11 USA.

Stripsearch, by Martin Rowson: The thing about the Human Rights Act …

Conspiracy of silence, by Al Weiwei: Saying the devastation of the Sichuan earthquake was partly manmade was not welcome.

To better days, by Rachael Jolley: The hope that kept the light burning during her editorship.

Plays, protests and the censor’s pencil, by Simon Callow: How Shakespeare fell foul of dictators and monarchs. Plus: Katherine E McClusky.

The enemies of those people, by Nina Khrushcheva: Khrushchev’s greatgranddaughter on growing up in the Soviet Union and her fears for the US press.

We’re not scared of these things, by Miriam Grace A Go: Trouble for Philippine

journalists.

Windows on the world, by Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee: Poems from Iran by two political prisoners.

Beijing’s fearless foe with God on his side, by Jimmy Lai: Letters from prison by the Hong Kong publisher and activist.

We should not be put up for sale, by Aishwarya Jagani: Two Muslim women in India on being ‘auctioned’ online.

Cartoon, by Ben Jennings: Liberty for who?

Amin’s awful story is much more than popcorn for the eyes, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Interview with the director of Flee, a film about an Afghan refugee’s flight and exile.

Women defy gunmen in fight for justice, by Témoris Grecko: Relatives of murdered Mexican journalist in brave campaign.

Chaos censorship, by John Sweeney: Putin’s war on truth, from the Ukraine frontline.

In defence of the unreasonable, by Ziyad Marar: The reasons behind the need

to be unreasonable.

We walk a very thin line when we report ‘us and them’, by Emily Couch: Reverting to stereotypes when reporting on non-Western countries merely aids dictators.

It’s time to put down the detached watchdog, by Fréderike Geerdink: Western newsrooms are failing to hold power to account.

A light in the dark, by Trevor Philips: Index’s Chair reflects on some of the magazine’s achievements.

Our work here is far from done, by Ruth Smeeth: Our CEO says Index will carry on fighting for the next 50 years.

In vodka veritas, by Nick Harkaway and Jemimah Steinfeld: The author talks about Anya’s Bible, his new story inspired by early Index and Moscow bars.

A ghost-written tale of love, by Ariel Dorfman and Jemimah Steinfeld: The novelist tells the editor of Index about his new short story, Mumtaz, which we publish.

‘Threats will not silence me’, by Bilal Ahmad Pandow and Madhosh Balhami: A Kashmiri poet talks about his 30 years of resistance.

A classic case of cancel culture, by Marc Nash: Remember Socrates’ downfall.

15 Dec 2021 | Academic Freedom Letters, Afghanistan, Africa, Americas, Asia and Pacific, Australia, Belarus, Brazil, Hong Kong, Kenya, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Malaysia, Malta, Middle East and North Africa, Politics and Society, religion & culture, Russia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, United States, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021 Extras

The Winter issue of Index magazine highlights the battles fought by theatre of resistance across the world and how they’ve been enduring different forms of censorship.

Writer Jonathan Maitland dives deeply into the history of theatre censorship in the United Kingdom and explains why British playwrights need to lose their fear and be bolder. Kaya Genç and Meltem Arikan provide a good overview of the situation in Turkey in the most recent years, where theatres have been closed down in Istanbul.

Natasha Tripney analyses the impacts of an exaggerated nationalism and how it restrains plays from moving forward.

The theatre of resistance, by Martin Bright: Index has a long history of promoting the work of dissident playwrights.

The Index: Free expression around the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern.

Women journalists caught in middle of a nightmare, by Zahra Nader: Many Afghan journalists –women in particular – have fled the Taliban or are in hiding from the brutal regime.

Hope in the darkness, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Nathan Law, one of the leaders of Hong Kong’s protest movement, is convinced that the repression will not last forever. We publish an extract from his new book.

Speaking up for the Uyghurs, by Flo Marks: Exeter university students have been successfully challenging the institution’s China policy, but much more needs to be done.

Omission is the same as permission, by Andy Lee Roth and Liam O’Connell: Malaysia’s introduction of emergency powers to deal with “fake news” was broadly ignored by the Western media – and that only emboldened the government.

I can run, but can I hide?, by Clare Rewcastle Brown: Journalist Clare Rewcastle Brown is a wanted woman in Malaysia – and the long reach of Interpol means there are now few places where she can consider herself safe.

Dream of saving sacred land dies in the dust, by Scarlett Evans: Australia’s mining industry is at odds with the traditional beliefs of the Aboriginal population and it is taking its toll on the country’s indigenous heritage.

Bylines, deadlines and the firing line, by Rachael Jolley: It’s not just pens and notebooks that journalists need in the USA, it’s sometimes gas masks and protective vests, too.

Cartoon, by Ben Jennings: “I’ve done my own research.”

Maltese double cross, by Manuel Delia: Four years on from Daphne Caruana Galizia’s murder, lessons have not been learned and justice for the investigative journalist’s family remains elusive.

“Apple poisoned me physically, mentally and spiritually”, by Martin Bright: A former Apple employee, who was fired by the tech giant after blowing the whistle on toxic waste under her office, says her fight will go on.[

]Keeping the flame alive as theatre goes dark, by Natasha Tripney: Theatre across the world is fighting new waves of repression, intolerance and nationalism, as well as financial cuts, at a time when a raging pandemic has threatened its existence.

Testament to the power of theatre as rebellion, by Kate Maltby: The Belarus Free Theatre, whose 16 members have now gone into exile to escape the Lukashenka regime, are preparing to perform at the Barbican in London.

My dramatic tribute to Samuel Beckett and catastrophe, by Reza Shirmarz: More than three decades after Index published the celebrated playwright’s work dedicated to the Czech dissident Vaclav Havel, the censored Iranian writer Reza Shirmarz has responded with his own play, Muzzled.

Why the Taliban wanted my mother dead, by Hamed Amiri: The author of The Boy with Two Hearts on why and how the family fled Afghanistan.

The first steps- Across Europe with Little Amal, by Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson: Good Chance Theatre on their symbolic take on the long journey of refugees from Syria to the UK.

Fighting Turkey’s culture war, by Kaya Genç: Theatres have been shuttered in Istanbul but the fightback by directors and playwrights continues.

I wrote a play then lost my home, my husband and my trust, by Meltem Arikan: The exiled Turkish playwright’s Mi Minör was blamed for the Gezi Park protests.

Where silence is the greatest fear, by Issa Sikiti da Silva: How Kenyan theatre has suffered under a succession of corrupt rulers, hot on the heels of colonial repression.

Censorship is still in the script, by Jonathan Maitland: British theatre has lost its backbone and needs to be more courageous.

God waits in the wings…ominously, by Guilherme Osinski and Mark Seacombe: A presidential decree that art must be ‘sacred’ has cast a free-speech shadow over Brazilian theatre.

Elephant that should be in Nobel Room, by John Sweeney: The winners of this year’s Peace Prize deserve their accolade, but there is another who should have taken the award.

We academics must fight the mob – now, by Arif Ahmed: The appalling hounding of Kathleen Stock at Sussex University is a serious threat to freedom of speech on campus.

So who is judging Youtube?, by Keith Kahn-Harris: Accused by the video behemoth of spreading misinformation, the author conducted an experiment in an effort to understand how the social media platform policies its content.

Why is the world applauding the man who assaulted me?, by Caitlin May McNamara: It is time for governments and businesses to decide where their priorities lie when it comes to the Middle East.

Silence is not golden, by Ruth Smeeth: As we enter a new year, Index will continue to act as a voice for those unable to use their own.

The road of no return, by Flo Marks and Aziz Isa Elkun: The Uyghur activist and poet, exiled in the UK, yearns for his family and friends imprisoned in Chinese concentration camps.

Bearing witness through poetry, by Emma Sandvik Ling: Poets are often on the frontlines of protest.

The people’s melody, by Mark Frary: For the first time, English readers can now experience the joys of Ethiopian poetry written in Amharic thanks to the work of Alemu Tebeje and Chris Beckett.

No corruption please, we’re British, by Oliver Bullough: The UK has developed a parallel vocabulary to avoid labelling anyone with the c-word … until now.