16 Mar 2017 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

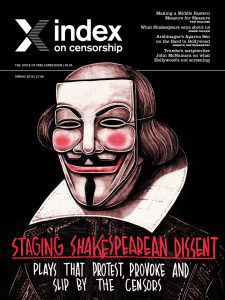

As freedom of speech in the arts, journalism and other mediums face significant challenges today, this event will explore the historic power of the arts in challenging power and promoting free speech.

Using the prism of Shakespeare, we will consider the various ways his work has been used throughout the centuries to channel dissent or used as propaganda and how the arts allow for greater freedoms of speech in our societies in the UK and US today. In partnership with Index on Censorship, this event will feature readings by 2016 Forward Prize winner and Trinidadian-British poet Vahni Capildeo and a panel discussion with renowned theatre director Dominic Dromgoole. For journalists, academics and students, this is truly an event not to be missed.

This program is part of Shakespeare Lives, a global program celebrating the continuing resonance of Shakespeare around the world led by the British Council and the GREAT Britain Campaign. The global program officially ended in 2016, but some activities will continue in the USA and worldwide in 2017.

This event is part of the Pen America World Voices Festival[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

When: Tuesday 2 May 2017 7:30-9 PM

Where: Roulette, 509 Atlantic Ave, Brooklyn, New York 11217 (map)

Tickets: $10 from Pen America World Voices Festival site

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Jan 2017 | Index in the Press

Several major literature and anti-censorship organizations have signed a statement defending publisher Simon and Schuster’s “right to publish” MILO’s upcoming book Dangerous, which has seen many others threaten to boycott the company. Read the full article

6 Jan 2017 | Index in the Press

Free speech organizations including the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) have begun to speak out in defense of Simon & Schuster after a book deal the publisher’s Threshold Editions imprint made with controversial Breitbart Tech editor Milo Yiannopoulos spurred widespread backlash, including calls to boycott S&S and to not review S&S titles. Read the full article

21 Dec 2016 | Magazine, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored, Volume 45.04 Winter 2016

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row” full_height=”yes” equal_height=”yes” css_animation=”none” css=”.vc_custom_1481548134696{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Sevan-Nişanyan-1460×490.jpg?id=82526) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Linguist and newspaper columnist SEVAN NIŞANYAN has found himself locked up for 16 years after being subjected to a torrent of lawsuits. Researcher JOHN BUTLER managed to interview him for the winter 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Well-known linguist Sevan Nişanyan will not be eligible for parole in Turkey until 2024. Locked up in the overcrowded Turkish prison system, he has found his initial relatively short jail sentence for blasphemy getting ever longer as he has been subjected to a torrent of “spurious” lawsuits on minor building infringements related to a mathematics village he founded.

Nişanyan, who is 60, spoke exclusively to Index on Censorship. He said he was being kept in appalling conditions. Moved from prison to prison since being jailed in January 2014, he is now being held in Menemen Prison, a “massively overcrowded and brain- dead institution”.

He added: “About two thirds of our inmates were recently moved elsewhere and the remainder pushed ever more tightly into overpopulated wards to make room for the thousands arrested in the aftermath of the coup attempt.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css=”.vc_custom_1481550218789{padding-bottom: 40px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Nişanyan is adamant that his time has not been wasted. He has been working on the third edition of his Etymological Dictionary of the Turkish Language, which presently stands at over 1500 pages“” font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:24|text_align:justify|color:%23dd3333″ google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic” css_animation=”fadeIn”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text el_class=”magazine-article”]

Nişanyan’s ordeal started in 2012 when he wrote a blog post about free speech arguing for the right to criticise the Prophet Mohammed. Through notes passed out of his high security prison via his lawyer, Nişanyan told Index what he believes happened next:

“Mr Erdoğan, the then-prime minister, believes in micromanaging the country. He was evidently incensed.

“I received a call from his office inquiring whether I stood by my, erm, ‘bold views’ and letting me know that there was much commotion ‘up here’ about the essay. The director of religious affairs, the top Islamic official of the land, emerged from a meeting with Erdoğan to denounce me as a ‘madman’ and ‘mentally deranged’ for insulting ‘our dearly beloved prophet’.

“A top dog of the governing party, who later became justice minister, went on air to assure us that throughout history, no ‘filthy attempt to besmirch the name of our holy prophet’ has ever been left unpunished. Groups of so- called ‘concerned citizens’ brought complaints of blasphemy against me in almost every one of our 81 provinces. Several indictments were made, and eventually I was convicted for a year and three months for ‘injuring the religious sensibilities of the public’.”

But what happened afterwards was even more sinister. He found himself, while in prison, facing eleven lawsuits relating to a village he was building with the mathematician and philanthropist Ali Nesin. Nişanyan has been involved for many years in a project to reconstruct in traditional style the village of Şirince, near Ephesus, on Turkey’s Western seaboard. It is now a heritage site and popular tourist destination. And nearby, he and Nesin have built a mathematics village which offers courses to mathematicians from all over Turkey and operates as a retreat for maths departments in other countries. They hope it will be the beginnings of a “free” university.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css=”.vc_custom_1481549931165{padding-bottom: 40px !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Jailing a non-Muslim, an Armenian at that, for speaking rather mildly against Islamic sensibilities… would be a first in the history of the Republic“” font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:24|text_align:justify|color:%23dd3333″ google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic” css_animation=”fadeIn”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

It was this project the Turkish authorities decided to focus on. Nişanyan was given two years for building a one-room cottage in his garden without the correct licence, then two additional years for the same cottage. Nine more convictions for infringements of the building code followed, taking his total term up to 16 years and 7 months.

He, and many others, are convinced that this is a political case, because jail time for building code infringements is almost unheard of in Turkey. He believes the authorities have prosecuted him for these crimes because they do not want his case to cause an international stir.

“Jailing a non-Muslim, an Armenian at that, for speaking rather mildly against Islamic sensibilities… would be a first in the history of the Republic,” he told Index. “It might raise eye- brows both here and abroad.”

Despite everything, Nişanyan is adamant that his time has not been wasted. He has been working on the third edition of his Etymological Dictionary of the Turkish Language, which presently stands at over 1500 pages.

On entering prison, he signed away most of his property, including the copyright to his books, to the Nesin Foundation which runs the mathematics village he is so passionate about. Today the village has added a school of theatre. A philosophy village is the next project in the works.

“The idea is, of course, to develop all this into a sort of free and independent university,” he said. “I am sure the young people who have come together in Şirince for this quirky little utopia will have the energy and determination to go on in my absence.”

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

John Butler is a pseudonym

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90772″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229908536530″][vc_custom_heading text=”Slapps and chills” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229908536530|||”][vc_column_text]January 1999

Julian Petley’s roundup looks at the bullying of broadcasters and asks: are they being SLAPPed around?[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89167″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422010388687″][vc_custom_heading text=”Survival in prison” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422010388687|||”][vc_column_text]December 2010

Detained writers suffer from violence, humiliation and loneliness – writing is their only solace.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93991″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533768″][vc_custom_heading text=”Writers on trial” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533768|||”][vc_column_text]October 1984

The trial outcome is uncertain, but it could mean putting Turkey’s leading intellectuals behind bars for 15 years.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fashion Rules” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F12%2Ffashion-rules%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The winter 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear.

In the issue: interviews with Lily Cole, Paulo Scott and Daphne Selfe, articles by novelists Linda Grant and Maggie Alderson plus Eliza Vitri Handayani on why punks are persecuted in Indonesia.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/12/fashion-rules/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]