Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

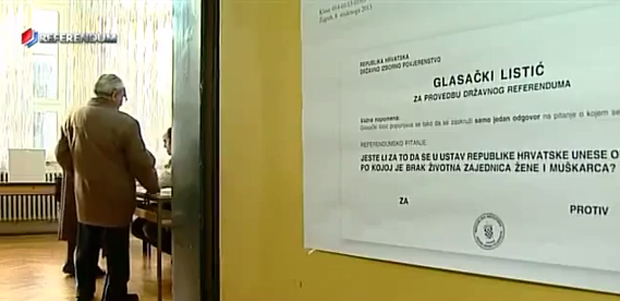

Croatians cast their votes on whether marriage should be constitutionally recognised as being between a man and a woman (Image: Mc Crnjo/YouTube)

Croatia’s voters moved Sunday to amend the country’s constitution to define marriage as being between a man and a woman. The campaign had been orchestrated by the country’s religious institutions. Sixty-five percent of voters supported a change that effectively bars gay marriage.

The campaign used some interesting and controversial tactics. Religious teachers in schools threatened students that they wouldn’t get a passing grade if they did not provide proof of their families’ support for the constitutional change. This was reported by an English language teacher from Split, the second largest city in Croatia, to the inspection body of the Ministry of Education around mid-November.

“If this is the situation in Split I believe it is even worse in smaller towns”, concluded the teacher who did not want to sign her name.

Following this, the media received numerous letters from school teachers confirming that religious teachers around Croatia were blackmailing students to make sure their family members vote “for the protection of the family” — the Catholic Church’s interpretation of the referendum question.

“If the president of the country and other public persons can talk about voting at the referendum why can’t a religious teacher do so?” commented Sabina Marunčić, senior advisor for religious education at the Croatian Education and Teacher Training Agency.

Since the call for a referendum on 8 November, the campaign has been the main topic of discussion in Croatia, despite the country facing a severe economic crisis and an unemployment rate of 20.3 per cent. While Croatian law defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman, this definition does not exist in the constitution. A recent announcement of a new law on same-sex partnerships has caused conservative movements to come together in the initiative “In the Name of Family”. They started spreading fear about gay marriage being legalised, despite the centre-left government showing no intention to do this. A 2003 law on same-sex partnerships has been seen as practically useless because it secures only a few, less important rights, and only after a relationship breaks down.

For weeks all anyone talked about was who will vote “for” and who will vote “against”, in the first national referendum in the Republic of Croatia set up by popular demand. The Social Democratic prime minister Zoran Milanović, President Ivo Josipović and numerous ministers all came forth against introducing the definition into the constitution. A large portion of powerful media was also openly against it. However, public opinion polls showed that 68 per cent of the citizens would vote for the proposal; 26 per cent against.

In the referendum campaign, the Catholic Church have firmly been advocating “for”. It has has a strong influence in the country of 4.29 million, with 86 per cent declaring themselves Catholic according to the latest census, released in 2011. The initiative “In the name of family” which has succeeded in gathering signatures of 740,000 citizens in order to hold a referendum is also linked to the Catholic Church.

“The church did not want to start the initiative for a referendum but it wholeheartedly accepted In the Name of Family, whose numerous members are conservative Catholics close to certain Croatian bishops,” says Hrvoje Crikvenec, editor of the religious portal Križ života (“Cross of Life”).

“However, I believe that the entire organisation and initiative is supported more by politics, that is, a marginal political right-wing party Hrast, than Croatian bishops. They have now become more involved in the campaign in the hope of what would for them be a positive outcome of the referendum, which would ultimately show them as winners.”

The initiative’s leaders do come from the non-parliamentary right-wing party Hrast, as well as conservative associations opposing the introduction of sex education in schools, artificial insemination and abortion. Some of them have been linked to Opus Dei, a secretive Catholic organisation which has been strengthening its presence in Croatia. In the Name of Family and the fight against a possible equal standing of homosexual and heterosexual marriages has provided them with the support of a larger portion of the public.

The Catholic Church has undoubtedly helped the success of a In the Name of Family. Signatures were gathered in front of churches and elsewhere, even in universities. Cardinal Josip Bozanić had written a note instructing priests to encourage believers in masses to attend the referendum and vote for the definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Group prayers for its success were also organised throughout Croatia in the lead up to the vote.

“We can’t blame the bishops for advocating the referendum from the altar because this is a part of the church’s program. They are more entitled do so than to say who to vote for at the elections, which they also do. However, it is inadmissible for religious teachers to influence children in schools,” university professor of philosophy and political commentator Žarko Puhovski says.

Despite Croatia being a majority Catholic country, every fourth marriage ends in divorce and a decreasing number of couples are deciding to marry.

“The church’s influence on citizens is far greater regarding political than moral views. Church morality is accepted in principle, but political views supported by the church gain additional power. That is why the referendum is causing a short-term increase in the influence of the church, which has for years been weakening,” Puhovski explains.

Church leaders are often complaining about the non-existent dialogue with the current, left-wing government, especially regarding the issues they consider to be related to religion – education of children, family care and marriage.

“The ultimate success of this referendum is in showing the power of the church in Croatia. It has shown the government that it can move masses of people so in the future, the government will have to think carefully before making any decision which could harm their interests,” said a group of Roman Catholic theologists in a joint letter made public on 29 November.

“The relationship between the church and the state has mostly been disturbed by militant statements of individuals from the Catholic Church leadership, which seem to be best served with a one common mindset rather than political and worldview pluralism,” sociologist and ex-ambassador for the Holy See, Ivica Maštruko says.

“We are not dealing with a normal criticism of the current social state and relations, but bigotry, inappropriate discourse and civilisational and religious malice,” Maštruko added.

An example of such a discourse is provided by reputable former minister and theologist Adalbert Rebić who, earlier this year, was quoted as saying: “The conspiracy of faggots, communists and dykes will ruin Croatia.” Pastor Franjo Jurčević was convicted for publishing homophobic and extremist posts on his blog.

But in the campaign for the referendum the Catholic Church was joined by representatives of the other most influential religious communities in Croatia – Orthodox Christians, Muslims, Baptists and the Jewish community Bet Israel. Together they supported the referendum and invited the believers to vote in order to “secure a constitutional protection of marriage”. Religious communities in Croatia are usually rarely seen forming such shared views.

“The most interesting thing is the agreement between the Catholic Church and the Serbian Orthodox Church which have in the past twenty years completely missed the chance to initiate reconciliation, dialogue and co-existence during and after the wars in ex-Yugoslavia. Religious communities in the region can obviously agree only when they find a common enemy, which in the case of this referendum are LGBT persons,” Cirkvenec says.

Žarko Puhovski considers it indicative that religious communities in Croatia succeed in forming shared views only with regards to sexual morality.

“They have failed to reach a consensus on any other moral or political issue,” he concludes.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

At the stroke of midnight on Sunday, Croatia officially became the 28th member of the European Union. Croatia will be a “serious, responsible and active member”, said President Ivo Josipovic as he ushered in “the first day of our European future”. But threats to freedom of expression, especially in the media, remain.

At the stroke of midnight on Sunday, Croatia officially became the 28th member of the European Union. Croatia will be a “serious, responsible and active member”, said President Ivo Josipovic as he ushered in “the first day of our European future”. But threats to freedom of expression, especially in the media, remain.

While the 2012 accession referendum was passed with the lowest ever turnout in a prospective member state, and enthusiasm has since waned further, today is a momentous occasion for a country that was at war only two decades ago – and still grapples with the aftermath. However, with the European Commission regarding freedom of expression a ‘key indicator’ for a country’s readiness to join the union, we should acknowledge that while Croatia has taken some important steps forward, there is work left to do.

The constitution guarantees freedom of expression and the press, and Croatia has recently seen a modest increase in its Freedom House global press freedom ranking, from 78 in 2009, to 64 this year. However, this comes after a significant tumble from 41 in 2007. Croatian journalists, especially those covering war crimes, organised crime and corruption, face continued threats to their well-being and livelihoods.

OSCE media freedom representative, Dunja Mijatovic has repeatedly expressed concerns about public broadcaster HRTs apparent practice of silencing critical journalists. Most recently, in March this year, journalists Denis Latin, Katja Kusec and Ruzica Renic were fired from HRT in suspicious circumstances.

In 2008, Ivo Pukanic, a journalist covering organised crime, intelligence and war profiteering was killed by a car bomb outside his office. It was the third attempt on his life, and also killed his associate Niko Franjic. Six men were convicted for the murders in 2010, but it is still unknown who commissioned the assassination.

This is far from the only attack on Croatian media. In 2007, journalist Zalko Peratovic was detained and his house searched for violating state secrets after publishing a story on war crimes on his blog. Owner of Nova TV, Ivan Caleta, and former media mogul Miroslav Kutle, have both been shot at. Ninoslav Pavic, co-owner of Croatia’s biggest publishing house had his car bombed. Andrej Maksimovic, editor of OTV, has been attacked twice. This handful of examples goes some way in explaining the overall environment of fear and intimidation that has chilled press freedom and consequently freedom of expression in Croatia.

But challenges to freedom of expression exist outside of the realm of the media too. While prison sentences for defamation were abolished in 2006, libel is a criminal offense punishable by fines. Given the country’s recent history, hate speech is not taken lightly. Hate speech based on race, religion, sexual orientation, nationality, ethnicity, or unspecified ‘other characteristics’ are punishable by up to five years in prison — three years if committed over the internet. Insulting ‘the Republic of Croatia, its flag, coat of arms or national anthem’ can bring up to three years in prison.

Unlike neighbouring countries Croatia has not banned gay pride parades, but freedom of assembly for Croatia’s LGBT population has still be under threat. When a parade was organised for the first time in Split in 2011, the small number of participants were pelted with eggs and rocks by thousands of counter-protesters. The police also failed to investigate an attack on six young men and women in the aftermath of the parade. Authorities have also come under fire for failure to investigate persistent acts of vandalism aimed at the country’s minority Serbian Orthodox community.

Despite this, some aspects of freedom of expression have improved recently. This year’s Zagreb pride parade saw its biggest turnout ever, as 15,000 people attended the peaceful march. In another positive development, this February, parliament adopted a Freedom of Information Act. A new body will be set up, specifically dedicated to freedom of expression, with greater focus on public interest and proactive publishing of information.

Croatian leaders and EU politicians have taken pains to stress that accession does not automatically solve the country’s problems. While they were largely referring to the economic situation, the same principle goes for freedom of expression. You only have to look to EU members like Hungary to see that membership alone does not necessarily improve media freedom. For Croatia, as with other recent additions to the union, membership is merely an initial, tentative step towards increased political and civil rights for its citizens.

Robert Ježić, majority owner of the Croatian daily Novi List, was arrested in Zagreb yesterday. His arrest is thought to be connected with the flight of former PM Ivo Sanader, who exited Croatia yesterday morning, hours before the parliament lifted his immunity from prosecution, thus opening pending corruption inquiries against him. Ježić, who is also the owner of the petrol-chemistry company Dioki, managed to pay considerably less for energy consumption thanks to Sanader, the anti-crime bureau USKOK revealed. Both Sanader and Ježić are alleged to be involved in the Hypo Alpe Adria Bank affair.

Journalists on Croatia’s Glas Istre (Voice of Istria) newspaper have entered their third day of strike action. They are protesting against wages and work places cuts. The ownership of Glas Istre, until recently one of the few independent newspapers in Croatia, became increasingly doubtful throughout the past years. Croatia’s Journalist Union and IFJ back the strike.

This is the biggest uprising of print journalists in Croatia since Slobodna Dalmacija’s case in 1993, when the newspaper was privatised through a series of dubious administrative decisions. Since then, similar privatisation patterns were applied to many other Croatian media outlets.