25 Apr 2017 | Academic Freedom, Hungary, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As a new law passed by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán’s government threatens the existence of Central European University in Budapest, 70,000 people marched in protest in the capital to save it as part of the #IStandWithCEU campaign.

Among those offering supportto protect the academic freedom of one of central Europe’s most prominent graduate universities, either by writing letters or demonstrating, include more than 20 Nobel Laureates including Mario Vargas Llosa, hundreds of academics worldwide, the European Commission, the UN, the governments of France and Germany, 11 US Senators, Noam Chomsky and Kofi Annan.

Whilst the amendment, which will effectively force CEU to shut, has been signed into statute by Hungarian president Janos Ader, the university hopes to challenge the law in the Hungary’s Constitutional Court.

In a video released on 20 April, Michael Ignatieff, president and rector of CEU, said: “Three weeks ago this university was attacked by a government who tabled legislation that would effectively shut us down. We fought back and the reception around the world has been just magnificent.”

He added: “Academic freedom is one of the values we just can’t compromise.”

Orsolya Lehotai, a masters student at CEU and one of the organisers of the street protest movement Freedom for Education, told Index that initially the small group of students had hoped to “mimic democratic society” and stop the law passing in its original form.

“So far in the seven years of the Orbán government, whenever there was big opposition to something, people have taken to the streets and this has actually changed legislation, so we decided it would show a little power if we were to have people in the streets about this,” Lehotai said. “Back then [at the first protest] we were unsure when the parliamentary debate was to happen but we had had news that it was to happen on a fast-track, which to us was outrageous.”

Despite the protests and international criticism, the Hungarian government said that the law is designed to correct “irregularities” in the way some foreign institutions run campuses. Government officials maintain that the legislation is not politically motivated.

Áron Tábor is a Fulbright scholar and another CEU student who has taken to the streets. He spoke to Index about the absurdity of the Hungarian government’s stance: “This is one university, where the language is instruction is English and the programs run according to the American system.The government says that CEU is a ‘phantom university’, or even a ‘mailbox university’, which doesn’t do any real teaching, but only issues American degrees from a distance. This is a ridiculous claim.”

Gergő Brückner, a journalist at Index.hu described the political paranoia that lies behind the new laws: “One important thing to know is that Fidesz doesn’t like anything that is not part of their own Fidesz system. You can be a famous filmmaker, a university researcher or an Olympic medal winner but you must, for them, be the part of the national circle of Fidesz.”

“If you are an independent and well-funded American university – then you are not controlled, and you can easily be portrayed as a kind of enemy,” he added.

Since its establishment in 1991, CEU has made no secret of its commitment to freedom of expression. It was founded by a group of intellectuals including George Soros, who has been much criticised by Orbán.

The university was designed to reinforce democratic ideals in an area of the world just emerging from communist control. This ethos continues: in February the annual president’s lecture at CEU was given by the University of Oxford academic Timothy Garton Ash who spoke on the topic of “Free Speech and the Defense of an Open Society”.

When the law comes into force, requirements for foreign higher education institutions to have a campus in their home country mean that it will be impossible for CEU to continue operating.

Similarly, requiring a bilateral agreement between the government of the country involved, and the Hungarian government is a huge obstacle, as in CEU’s case this would be the USA but the US federal government has made it clear that it is not within their competence to negotiate this.

More generally, the ability of the Hungarian government to block any agreement raises worrying possibilities, too. Professor Jan Kubik told Index: “A democratic government has no business in the area of education, particularly higher education, except for providing funds for it. When a government tries to play an arbiter, dictating who does and who does not have the right to teach that is a sure sign of authoritarian tendency.”

Kubik, director of University College London’s School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies, along with over a thousand other international academics, has strongly criticised the new legislation, and his department is holding a rally in London on April 26.

He has also signed an open letter published in the Financial Times.

He said: “Any governmental attempt to close down a university is always very troubling. An attack on a university in a country that has already been travelling on a path towards de-democratisation for a while is alarming.

“Universities are like canaries of freedom and independence of the public sphere. Their death or weakening signals trouble for this sphere, a sphere that is indispensable for democracy.”

With the international condemnation of the Lex CEU amendment and a likely protracted legal battle ahead, what Kubik called “a magnificent institution of higher learning, as devoted to the freedom of intellectual inquiry and high ethical standards as any of the best universities in the world” is not expected to shut its doors this year.

Meanwhile, those fighting for fundamental freedoms in Hungary will continue to challenge Orbán. European Commission vice president Frans Timmermans said, CEU has been a “pearl in the crown” of central Europe that he would “continue to fight for”, and for as long as global opinion remains so loudly behind CEU, Orbán will find it an institution difficult to silence. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1493126838618-e2c5cf5d-d00a-0″ taxonomies=”2942″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Mar 2017 | Awards, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Hungary’s high tide of populism was beaten back briefly in October 2016 when prime minister Viktor Orban’s referendum on closing the door on refugees was ruled invalid after just 44% of the population bothered to show up and vote.

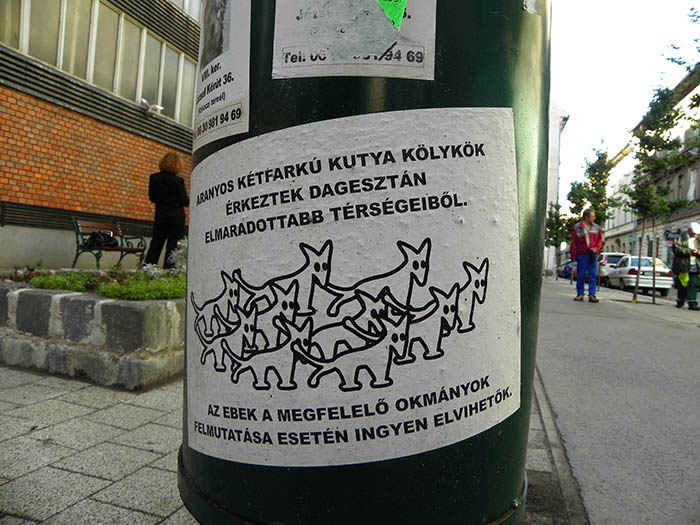

The country’s Two-tailed Dog Party don’t take credit for the result, but were certainly part of the mass soft power endeavour that defeated the referendum, and they used a tact rarely seen in Hungarian politics today: humour.

They urged voters to “Vote invalidly!” by answering both yes and no. “A stupid answer to a stupid question.”

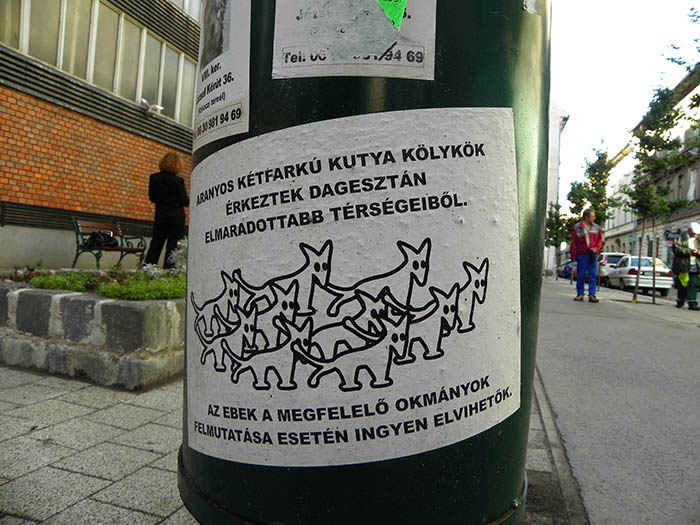

What officially became known as the Two-tailed Dog Party in 2006 has been around since 2000, when it was a group of street artists fronted by Gergely Kovács. In their current form they parody political discourse in Hungary with artistic stunts and creative campaigns.

The Two-tailed Dog is a vital alternative voice following the rise of Orban and is now a registered political party ready to contest in 2018’s parliamentary elections. They can no longer be written off as a joke.

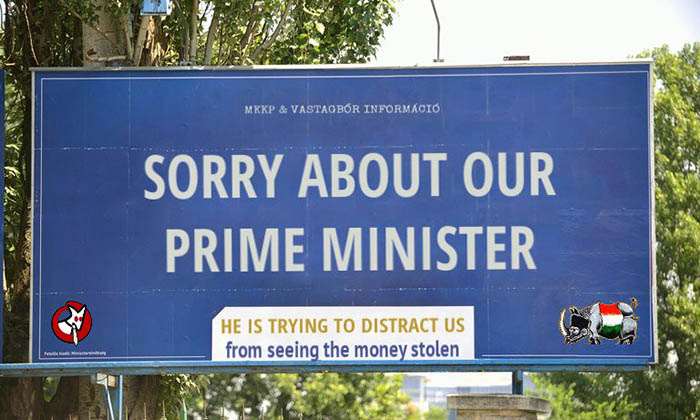

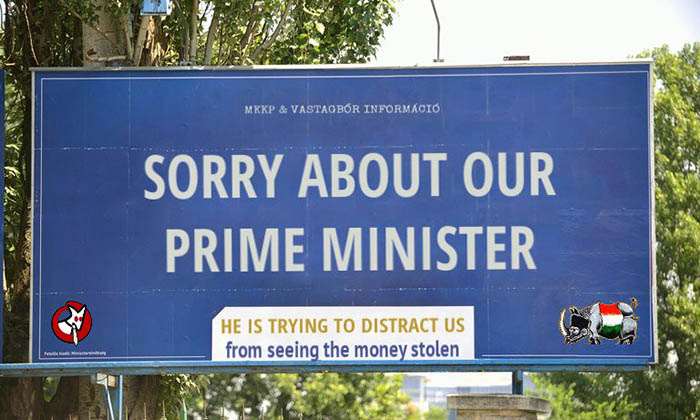

When the prime minister started plastering Hungary with anti-immigrant posters with slogans like “If you come to Hungary, you may not take jobs away from Hungarians,” and “If you come to Hungary, you must respect our culture,” the Two-tailed Dog responded with a billboard campaign of their own: “If you are Hungary’s prime minister, you have to obey our laws,”; “Come to Hungary by all means, we’re already working in London.”

The lampooning was largely crowdfunded, and volunteers from around the country were on hand to erect 500 outdoor billboards and over 100,000 smaller posters.

When Orban introduced the national consultation on immigration and terrorism in 2015, as part of a series of xenophobic measures to repel tens of thousands of migrants and refugees, and plastered cities with anti-immigrant billboards, the Two-tailed Dog launched mock questionnaires and even more billboards and posters.

Relentlessly attempting to reinvigorate public debate and draw attention to under-covered taboo topics, the party’s recent efforts also include painting broken pavement to draw attention to a lack of public funding.

“It would be important for people to be able to discuss things again and for the atmosphere in the country to finally improve and change back to normal,” Kovács says.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content” equal_height=”yes” el_class=”text_white” css=”.vc_custom_1490258749071{background-color: #cb3000 !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Support the Index Fellowship.” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:28|text_align:center” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsupport-the-freedom-of-expression-awards%2F|||”][vc_column_text]

By donating to the Freedom of Expression Awards you help us support

individuals and groups at the forefront of tackling censorship.

Find out more

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″ css=”.vc_custom_1490258649778{background-image: url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/donate-heads-slider.jpg?id=75349) !important;background-position: center !important;background-repeat: no-repeat !important;background-size: cover !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1490271092003-8af6e4a2-7218-9″ taxonomies=”8734″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 May 2016 | Hungary, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

In early April 2016, major Hungarian news website vs.hu began publishing less than normal. On 25 April a dozen journalists, including editor-in-chief Olivér Lebhardt, resigned. While the newsroom is still functioning, its future is yet to be decided by its owners, according to daily newspaper Népszabadság.

The mass resignation was prompted by revelations that the site, owned by New Wave Media (NWM), had received funding from foundations established by the Hungarian National Bank, the country’s central bank. The financing totaled more than 500 million HUF ($1.8 million).

NWM is owned by Czech company Bawaco Invest, which, Hungarian news site 444.hu reported, can be linked to Tamás Szemerey, a cousin of the central bank’s governor, György Matolcsy. The company issued a statement denying Szemerey’s ownership, according to the Financial Times.

The educational foundations were established in 2014 by Matolcsy, a politician allied to Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán. The foundations were endowed with over 314 billion forints ($1.1 billion) of central bank funding that was then invested in government bonds, Reuters reported.

The finances of these foundations were kept secret, but after a ruling from the country’s constitutional court in March, their contracts were published on 22 April 2016. Since then, the press has delighted in revelations of the foundations’ profligacy, The Economist wrote. The bank’s foundations spent money on real estate and artworks, as well as funding web projects covering social and economic issues.

“I was informed by the editor-in-chief a day before [the NWM disclosures], on Wednesday 21 April 2016,” Attila Bátorfy, one of the journalists who resigned told Index on Censorship. “That day there was a meeting, where István Száraz, the CEO of the publishing company deferred to answer the journalist’s questions. Then on Friday, he was talking about only a couple hundred of million HUF, but we knew there would be a huge scandal.”

On the evening of 23 April the first articles about the foundations’ spending were published. The next day vs.hu journalists issued a joint statement saying that while some of them knew that part of their editorial projects were sponsored by the bank’s foundations, they had no knowledge of the extent of the financing, Bátorfy recalled.

“We are also surprised and shocked by the data published by the foundations,” the journalists wrote. The editorial team said that there was no interference with the content of the articles — even in projects that were sponsored.

“On that Saturday evening, we held an emergency meeting in my apartment. About 15 colleagues were present, and we talked about the minimal requirements we, as journalists, expect from our publisher, to consider continuing our work at vs.hu. We had no opportunity to present these demands, because in his opening speech the CEO made it clear that the situation is beyond hope,” Bátorfy recalled.

“Journalists started to hand in their resignations. Those working for the politics, economy, culture and multimedia sections said the situation made their work impossible, they lost credibility, and there is no reason to continue,” he told Index.

Bátorfy, who had worked for vs.hu for three months, said that he had accepted the role after he was told that the site was financed by private and state advertising and money from the owner.

In the wake of the revelations, the Editor-in-Chief’s Forum issued a statement asking parliament to pass a law that would require the transparent disclosure of ownership and state funding of media outlets. “This would be beneficial to the market transparency, and would decrease the defenselessness of the media workers,” the group said.

Hungary’s ruling conservative Fidesz party has been making changes to the country’s media market since it came to power in 2010. Most recently the government cut funding to culture magazines. In 2015 Hungarian public media laid off scores of journalists as its funding was cut, according to reports on MMF. In the case of Hungarian private TV station RTL Klub, an ongoing conflict led to a ban of its news reporters and the dismissal of the television network’s CEO. Observers like 2014 Index award-winning Tamás Bodoky have noted that government advertising contracts have been used as a “powerful censorship instrument”.

Access to information was restricted through a series of amendments in the freedom of information law in July 2015, but the free movement of journalists in the parliament building was also strictly regulated. As a consequence, journalists trying to ask questions about the National Bank scandal were banned from the Parliament.

On Tuesday 26 April 2016, a number of media outlets received notes from House Speaker László Kövér, in which the Fidesz politician informed them that their journalists were barred from entering the building for “filming without a permit” and “consciously breaking the rules”. The ban came a day after journalists attempted to question Fidesz politicians, including Orbán and Kövér. While journalists and camera crews followed MPs, they entered into a secure area that was out of bounds to members of the press.

The editor-in-chief of Népszabadság newspaper (nol.hu), András Murányi, wrote a response to the letter: “I can assure you that Népszabadság had no intention of breaking the rules. The goal of journalists working at Népszabadság was to ask those who are elected and are paid representatives of the people questions regarding public affairs, and to publish their answers. As for answers – as we could see this time again – we seldom get any, as we are more and more prevented to act as free press in Parliament (…) lately we can only do our job in a constricted area,” Murányi said.

21 Jan 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Hungary, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

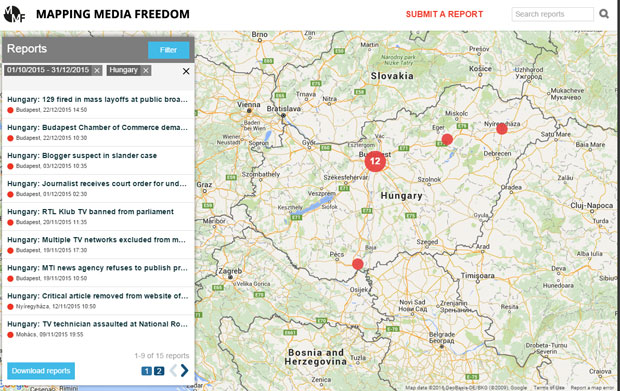

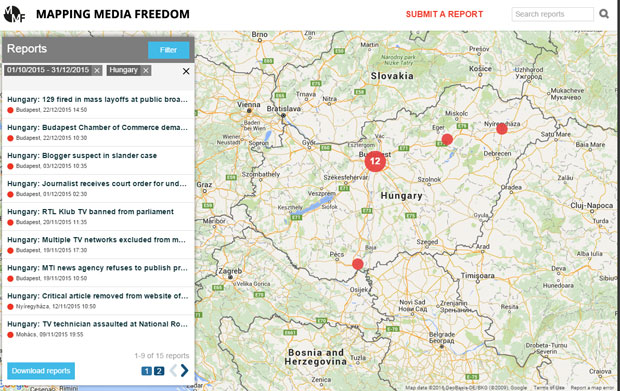

Hungary’s media outlets are coming under increasing pressure from lawsuits, restrictions on what they can publish and high fees for freedom of information requests, according to a survey of the 15 verified reports to Index on Censorship’s media monitoring project during the fourth quarter of 2015.

The Mapping Media Freedom project, which identifies threats, violations and limitations faced by members of the press throughout the European Union, candidate states and neighbouring countries, has recorded 129 verified incidents in Hungary since May 2014. In the fourth quarter of 2015 the country had the second-highest total of verified reports among EU member states and the sixth highest total among the 38 countries monitored by Mapping Media Freedom.

In 2015, Hungary was ranked #65 (partially free) on the World Press Freedom Index compiled by Reporters Without Borders. Only two EU member states, Greece and Bulgaria received a worse score.

In autumn 2015, the law governing freedom of information (FOI) was amended after a series of investigative reports uncovered wasteful government spending through FOI requests. Under the changes, the Hungarian government was granted sweeping new powers to withhold information and allowed the government and other public authorities to charge a fee for the “labour costs” associated with FOI queries. Critics warned that fees would prevent public interest journalism, and, in at least one case, it appears they were right.

In other cases, journalists have been sued for slander and issued court orders for undercover reporting on the refugee crisis.

Here are the 15 reports with links to more information.

- 22 December 2015: Budapest Chamber of Commerce demands high price to answer FOI request

The Budapest Chamber of Commerce (BCCI) asked for 3-5 million HUF ($10,356-16,352) to answer a freedom of information (FOI) request submitted by channel RTL Klub. The Budapest Chamber of Commerce and Industry said that the price will cover the salaries of 2-3 employees who would be given the task to respond to the FOI regarding BCCI’s spending and finances.

- 22 December 2015: 129 fired in mass layoffs at public broadcaster

Even the jobs of those who work for the government-friendly state broadcaster are far from being secure. On 22 December 2015, 129 employees were laid off by the umbrella company for public service broadcasters (MTVA) in pursuit of “operational rationalisation”.

Those fired included journalists, editors and foreign correspondents. According to the MTVA, the reason for the dismissal was the “better exploitation of synergies”, “increase of efficiency” and “cost reduction”.

- 3 December 2015: Blogger suspect in slander case

András Jámbor, a blogger is suspect in a slander case because he refuted the claims of Máté Kocsis, the mayor of Józsefváros (8th district of Budapest). In August 2015, Mayor Kocsis published a Facebook post alleging that the refugees have been making fires, littering, going on rampage, stealing and stabbing people in parks.

In response, Jámbor wrote a post for Kettős Mérce blog, disproving the mayor’s claims. He added that “Máté Kocsis is guilty of instigation and scare-mongering”. The mayor denounced him for slander.

On 3 December 2015, Jámbor confirmed to police that he is the author of the blog post and sustains the affirmations he made. The police took fingerprints and mugshots of the journalist.

- 1 December 2015: Journalist receives court order for undercover report on refugee camps

Gergely Nyilas, a journalist working for Hungarian online daily Index.hu, was summoned to court for his undercover report on refugee camp conditions published in August 2015.

The journalist reentered Hungary’s borders with a group of asylum seekers and, upon being detained, told the border guards that he was from Kyrgyzstan. Dressed in disguise, Nyilas reported on his treatment by border guards, the conditions at the Röszke camp, a bus ride and his experience at the police station in Győr. He eventually admitted he was Hungarian, at which point the police let him go, the Budapest Beacon reported.

Based on a police investigation, prosecutors first charged Nyilas with lying to law enforcement officials and forging official documents. The charges were then dropped but prosecutors still issued a legal reprimand against the journalist.

- 20 November 2015: Parliament speaker bans RTL Klub TV

On 20 November 2015, László Kövér, the speaker of the parliament has banned RTL Klub television from entering the parliament building, saying that the crew broke parliament rules on press coverage. According to Kövér, the journalists were filming in a corridor, where filming was forbidden, and then refused to leave the premises after they were repeatedly asked to.

The day before, on 19 November, RTL Klub was not allowed to participate at a press conference held by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and NATO secretary general Jens Soltenberg in parliament.

RTL Klub, along with other Hungarian media outlets such as 444.hu or hvg.hu, were not invited to the press conference, but RTL Klub journalists still showed up. They attempted to enter the room with the camera rolling but were denied access. This incident reportedly led to the ban on their access.

- 19 November 2015: Multiple TV networks excluded from major press conference

RTL Klub TV, 444.hu and hvg.hu journalists were not invited to a joint press conference held in parliament by Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and NATO secretary general Jens Soltenberg.

RTL Klub journalists still attempted to attend by entering the room with a camera already rolling but were still barred from entering.

They were told that the meeting was “private”, and journalists were not allowed to ask questions. Bertalan Havasi, the press secretary for the Hungarian prime minister, told them that their pass was only for the plenary session and that they must leave. However, state media outlets like M1 were allowed live transmission of the press conference, and MTI, the Hungarian wire service also published a piece about the meeting.

- 19 November 2015: MTI news agency refuses to publish press release

Publicly funded news agency MTI refused to publish a press release by Hungarian Socialist Party vice president Zoltán Lukács, where he asked for a wealth gain investigation into István Tiborcz, the son-in-law of the Hungarian prime minister. MTI refused to publish the press release, claiming that István Tiborcz is not a public figure.

The business interests of the son-in-law of Prime Minister Victor Orbán are widely discussed in the Hungarian media, especially because companies connected to Tiborcz are frequently winning public procurement tenders.

- 12 November 2015: Critical article removed from website of local newspaper

An article about a photo manipulation of Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán was removed from the website of Szabolcs Online.

The article titled, A Mass of People Saluted Viktor Orbán at Nyíregyháza – Or Not?, had a photo showing that only two dozen people gathered around the Hungarian prime minister visiting the city of Nyíregyháza. Soon after the piece was published, it was removed from the szon.hu website. However, it was reportedly still available temporarily in Google cache.

The article was a reaction to a photo published by the state news agency, MTI, that was shot in such a way that it leaves the impression that there was a big crowd around the prime minister.

- 9 November 2015: TV technician assaulted at National Roma Council meeting

A technician working for Hír TV news television was assaulted at a meeting of the National Roma Council held in the city of Mohács. The technician was standing near a door, when the daughter of a member of the National Roma Council, hit him in the stomach, as she was leaving the room.

The mother of the aggressor, Jánosné Kis denied any wrongdoing, although her daughter actions were captured on film.

- 4 November 2015: Government could force media to employ secret service agents

Hungarian media is demanding that the government repeal a plan that could force newspapers, television and radio stations as well as online publications to add agents from the constitution protection office (national intelligence and counterintelligence) to their staff, the Associated Press reported.

The Hungarian publishers’ association claimed that if the draft proposal by the interior ministry is passed by parliament, it could “harshly interfere with and damage” media freedom, and would facilitate censorship. The association represents over 40 of Hungary’s largest media companies.

- 4 November 2015: Government official asks to criminalise defamation in media law

Geza Szocs, the cultural commissioner in the Hungarian Prime Ministry, has asked for a modification of Hungary’s media law that would criminalise defamation, in an article for mandiner.hu. Szocs has also asked for a stricter regulation of damages caused by defamatory articles.

The commissioner wrote the piece in response to a series of articles published by index.hu, which criticised the Hungary’s presence at the 2015 Milan World Fair, a project that Szocs was managing.

- 26 October 2015: Journalist told to delete photographs of government official

A journalist working on a profile of András Tállai, Hungarian secretary of state for municipalities, was asked to delete pictures he had taken of the politician eating scones.

“Don’t take pictures of the state secretary while he is eating,” a staff member told the journalist, who works for vs.hu.

The journalist briefly interviewed Tállai, who is also head of the Hungarian Tax Authority, in the township of Mezőkövesd, where the politician started the conversation by asking, “Why do you want to write a negative article about me?”. Tállai then smiled and asked the journalist, “You are registered at the Tax Authority, right?”

- 22 October 2015: Public radio censors interview with prominent historian

Editors at MR I Kossuth Rádió, part of Hungarian public radio, did not broadcast an interview with János M. Rainer, one of the most acclaimed historians on the 1956 Hungarian revolution.

“We don’t need a Nagy Imre-Rainer narrative!” was the justification given by one of the editors to censor the content, the reporter who interviewed Rainer claimed.

- 17 October 2015: State press agency refuses to publish opposition party press release

Hungarian state news agency MTI refused to publish a press release issued by Lehet Más a Politika (LMP), an opposition parliamentary party.

In the press release, LMP criticised MTI by stating the Hungarian government is spending more money every year on the news agency, yet MTI fails to meet the standards of impartiality and is being transformed into a government propaganda machine.

- 7 October 2015: National press barred from asking questions at conference

Hungarian journalists were not allowed to ask questions at a press conference held after a meeting between the Hungarian president János Áder and the PM of Croatia, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic.

Only international journalists from Reuters and the Croatian state television were allowed to ask the politicians questions.