Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The spring issue of Index magazine is special. We are celebrating 50 years of history and to such a milestone we’ve decided to look back at the thorny path that brought us here.

Editors from our five decades of life have accepted our invitation to think over their time at Index, while we’ve chosen pieces from important moments that truly tell our diverse and abundant trajectory.

Susan McKay has revisited an article about the contentious role of the BBC in Northern Ireland published in our first issue, and compares it to today’s reality.

Martin Bright does a brilliant job and reveals fascinating details on Index origin story, which you shouldn’t miss.

Index at 50, by Jemimah Steinfeld: How Index has lived up to Stephen Spender’s founding manifesto over five decades of the magazine.

The Index: Free expression around the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern.

“Special report: Index on Censorship at 50”][vc_column_text]Dissidents, spies and the lies that came in from the cold, by Martin Bright: The story of Index’s origins is caught up in the Cold War – and as exciting

Sound and fury at BBC ‘bias’, by Susan McKay: The way Northern Ireland is reported continues to divide, 50 years on.

How do you find 50 years of censorship, by Htein Lin: The distinguished artist from Myanmar paints a canvas exclusively for our anniversary.

Humpty Dumpty has maybe had the last word, by Sir Tom Stoppard: Identity politics has thrown up a new phenonemon, an intolerance between individuals.

The article that tore Turkey apart, by Kaya Genç: Elif Shafak and Ece Temulkuran reflect on an Index article that the nation.

Of course it’s not appropriate – it’s satire, by Natasha Joseph: The Dame Edna of South Africa on beating apartheid’s censors.

The staged suicided that haunts Brazil, by Guilherme Osinski: Vladimir Herzog was murdered in 1975. Years on his family await answers – and an apology.

Greece haunted by spectre of the past, by Tony Rigopoulos: Decades after the colonels, Greece’s media is under attack.

Ugandans still wait for life to turn sweet, by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Hopes were high after Idi Amin. Then came Museveni …People in Kampala talk about their

problems with the regime.

How much distance from Mao? By Rana Mitter: The Cultural Revolution ended; censorship did not.

Climate science is still being silenced, by Margaret Atwood: The acclaimed writer on the fiercest free speech battle of the day.

God’s gift to who? By Charlie Smith: A 2006 prediction that the internet would change China for the better has come to pass.

50 tech milestones of the past 50 years, by Mark Frary: Expert voices and a long-view of the innovations that changed the free speech landscape.

Censoring the net is not the answer, but… By Vint Cerf: One of the godfathers of the internet reflects on what went right and what went wrong.[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”Five decades in review”][vc_column_text]An arresting start, by Michael Scammell: The first editor of Index recounts being detained in Moscow.

The clockwork show: Under the Greek colonels, being out of jail didn’t mean being free.

Two letters, by Kurt Vonnegut: His books were banned and burned.

Winning friends, making enemies, influencing people, by Philip Spender: Index found its stride in the 1980s. Governments took note.

The nurse and the poet, by Karel Kyncl: An English nurse and the first Czech ‘non-person’.

Tuning in to revolution, by Jane McIntosh: In revolutionary Latin America, radio set the rules.

‘Animal can’t dash me human rights’, by Fela Kuti: Why the king of Afrobeat scared Nigeria’s regime.

Why should music be censorable, by Yehudi Menuhin: The violinist laid down his own rules – about muzak.

The snake sheds its skin, by Judith Vidal-Hall: A post-USSR world order didn’t bring desired freedoms.

Close-up of death, by Slavenka Drakulic: We said ‘never again’ but didn’t live up to it in Bosnia. Instead we just filmed it.

Bosnia on my mind, by Salman Rushdie: Did the world look away because it was Muslims?

Laughing in Rwanda, by François Vinsot: After the genocide, laughter was the tonic.

The fatwa made publishers lose their nerve, by Jo Glanville: Long after the Rushdie aff air, Index’s editor felt the pinch.

Standing alone, by Anna Politkovskaya: Chechnya by the fearless journalist later murdered.

Fortress America, by Rubén Martínez: A report from the Mexican border in a post 9/11 USA.

Stripsearch, by Martin Rowson: The thing about the Human Rights Act …

Conspiracy of silence, by Al Weiwei: Saying the devastation of the Sichuan earthquake was partly manmade was not welcome.

To better days, by Rachael Jolley: The hope that kept the light burning during her editorship.

Plays, protests and the censor’s pencil, by Simon Callow: How Shakespeare fell foul of dictators and monarchs. Plus: Katherine E McClusky.

The enemies of those people, by Nina Khrushcheva: Khrushchev’s greatgranddaughter on growing up in the Soviet Union and her fears for the US press.

We’re not scared of these things, by Miriam Grace A Go: Trouble for Philippine

journalists.

Windows on the world, by Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee: Poems from Iran by two political prisoners.

Beijing’s fearless foe with God on his side, by Jimmy Lai: Letters from prison by the Hong Kong publisher and activist.

We should not be put up for sale, by Aishwarya Jagani: Two Muslim women in India on being ‘auctioned’ online.

Cartoon, by Ben Jennings: Liberty for who?

Amin’s awful story is much more than popcorn for the eyes, by Jemimah Steinfeld: Interview with the director of Flee, a film about an Afghan refugee’s flight and exile.

Women defy gunmen in fight for justice, by Témoris Grecko: Relatives of murdered Mexican journalist in brave campaign.

Chaos censorship, by John Sweeney: Putin’s war on truth, from the Ukraine frontline.

In defence of the unreasonable, by Ziyad Marar: The reasons behind the need

to be unreasonable.

We walk a very thin line when we report ‘us and them’, by Emily Couch: Reverting to stereotypes when reporting on non-Western countries merely aids dictators.

It’s time to put down the detached watchdog, by Fréderike Geerdink: Western newsrooms are failing to hold power to account.

A light in the dark, by Trevor Philips: Index’s Chair reflects on some of the magazine’s achievements.

Our work here is far from done, by Ruth Smeeth: Our CEO says Index will carry on fighting for the next 50 years.

In vodka veritas, by Nick Harkaway and Jemimah Steinfeld: The author talks about Anya’s Bible, his new story inspired by early Index and Moscow bars.

A ghost-written tale of love, by Ariel Dorfman and Jemimah Steinfeld: The novelist tells the editor of Index about his new short story, Mumtaz, which we publish.

‘Threats will not silence me’, by Bilal Ahmad Pandow and Madhosh Balhami: A Kashmiri poet talks about his 30 years of resistance.

A classic case of cancel culture, by Marc Nash: Remember Socrates’ downfall.

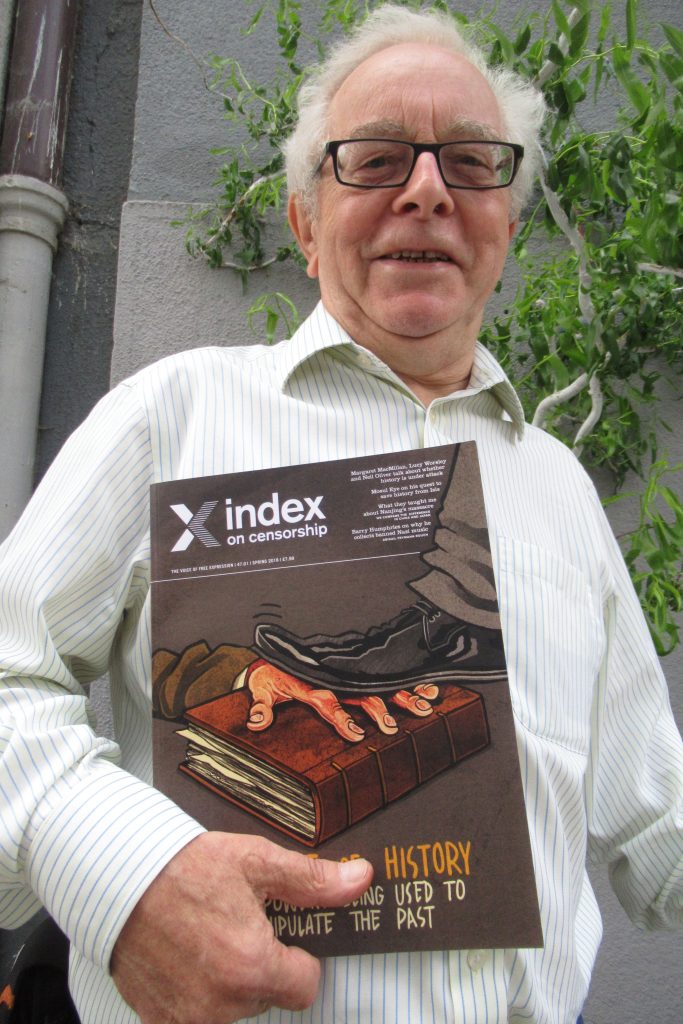

2018 winner of the George Theiner Award David Short with a copy of Index on Censorship magazine

British academic David Short has been announced as the recipient of the George Theiner Award 2018.

Named in honour of George, also known as Jiri, Theiner, the former editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine, the literary award is given to people and organisations outside the Czech Republic, who have made long-term contributions to the promotion of Czech literature and free expression across the globe.

George Theiner was widely respected by writers and poets in Czechoslovakia and across the globe for his work translating Czech works into English, including Vaclav Havel, Ivan Klima,

and Ludvik Vaculik. Theiner was the deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine throughout the 1970s, and, following Michael Scammell’s departure, as the editor in the 1980s.

First awarded in 2011 and created by World of Books, the award is presented at the Prague book fair in May each year. The winner is decided by a five-person jury, and also receives a prize of £1000.

This year’s winner Short is a British academic who taught Czech and Slovak at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London, from 1973 to 2011. Over the years he has translated various Czech works into English, including a number of Slovak authors and also created a well-respected Czech-English/English-Czech dictionary, all of which contributed to the profile of Czech authors and literature abroad.

Pavel Theiner, son of George, said: “As always, the recipient has in a major way, and over a long period, contributed to the promotion of Czech literature abroad. David Short is remarkably modest, multilingual, an expert in terms of the grammar and his Czech-English/English-Czech dictionary is extremely well respected.”

Previous winners include Ruth Bondy, who won the award in 2012. Bondy was an Auschwitz and Theresienstadt survivor who moved to Israel after the war to work as a journalist for Hebrew daily newspaper Davar. She taught journalism at the Tel Aviv University in the 1980s and 1990s, as well as translating a number of Czech authors into Hebrew, including the first translation into Hebrew of Hasek´s Good Soldier Schweik. Bondy sadly passed away in November 2017 aged 94.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Playwright Javaad Alipoor told The Guardian that “the response to radicalism is to shut down debate for young people”. His play The Believers Are But Brothers will be performed at the Bush Theatre beginning 24 January 2018.

It’s easy to dismiss the importance of arts in a democracy; its social value is disregarded when it is seen as the province of the rich and privileged. Yet when we look to more authoritarian regimes across the globe Index is reminded constantly of the importance of the role of arts as a voice of dissent and the extraordinary amount of time that repressive states spend suppressing it. If the spoken or written word, if performance or image did not have power, then dictators wouldn’t spend so much time actively silencing and persecuting artists.

But let’s not just look to repressive regimes when we want to talk about censorship. Artists are often the canaries in the mine, a leading barometer of freedom in any country, with the ability to powerfully capture uncomfortable truths. The consequences are different here in the UK, we don’t imprison artists or worse, but ensuring the creation of work by artists who are by law, free to speak, means creating the environment in which risks can be taken.

Yet, in the UK in 2017, when arts have a critically, crucially important role to express and process the diverse and often divergent opinion and experience that coexist in our society, we have created a risk-averse culture. A raft of social, legal and political pressures threaten to limit the space available for expression. New legislation, lack of clarity around policing roles and responsibilities, fear of media backlash or social media storm, loss of funding, means that arts organisations are not always confident about taking the kinds of risks they would like – or indeed need – to make the best art. If only a few groups feel able to explore the most difficult subjects or give voice to underrepresented communities, then, when something goes wrong, it gets harder for the entire arts community to address sensitive issues.

In 2010, when I started in this work, freedom of expression was not a priority for the arts sector; it was assumed safe and left to fend for itself. This never works, as Michael Scammell, the first editor of Index reminds us: “Freedom of expression is not self-perpetuating…”.

When we asked a conference of theatre directors at the time which was more important: audience development or freedom of expression, 100% said the former. Audience development, as I understand it, is about bringing in new audiences, reaching out to find fresh creative voices and breaking the homogenous mould of arts audiences. Yet the call for inclusivity and equality of access has tended to be resolved around a desire to please and a fear of offending, leading to a loss of appetite for the unpopular expression and risk-taking, as identified in Index’s 2013 conference Taking the Offensive and numerous case studies as part of Index’s Art and the Law guides. And still the arts remain obstinately homogenous.

Playwright, director Javaad Alipoor said in a recent interview with Index: “There is a whole discourse about risk [in the theatre industry] that we need to shift. We take risks all the time, but the way we are willing to do it is mega-racialised. Some people are a risk and some people aren’t a risk. I overheard some relatively sensible liberal people describing the appointment of Kwame Kwei-Armah [ newly appointed director of the Young Vic] as a bold move. I thought – it’s a good move. Here is an internationally successful guy, running an internationally successful theatre.”

Look at the two 2015 plays about radicalisation: Homegrown, commissioned by the National Youth Theatre (NYT) written and directed by Nadia Latif and Omar El Khairy, was cancelled; Another World – Losing our Children to Islamic State – by Gillian Slovo and developed by Nicolas Kent, commissioned by the National Theatre, was produced. Whatever else might have happened at NYT, the fact remains that Latif and El Khairy, two creatives from a Muslim background, and the 115 young people they were working with, were not allowed to speak, while two establishment figures were free to express their view of the same issue. This illustrates Alipoor’s point perfectly.

Add to this the role of the police in cancelling work, going all the way back to Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti in Birmingham in 2004; more recently the removal of ISIS Threaten Sylvania on the advice of the police in 2015; the policing of the Boycott the Human Zoo picket that led to the cancellation of the Barbican production of Exhibit B in London; the banning of music performances by police in Leicester and Bristol at the behest of local Islamic leaders. All point to the uneasy relations between state, the arts sector and artistic expression about issues of race and religion. A policing pattern has emerged, in which it is easier to remove what is deemed to be provocative and so dispel or prevent protest, than manage the situation and allow the artwork to go ahead. The arts sector has been caught out each time.

This pattern of policing interferes with the fundamental right to freedom of expression, something Index has taken up with National Police Lead on Public Order. Index is now working with a Senior Police Trainer to develop better support for the arts sector. His team will contribute to our training programme next year, which will also feature an introduction to our guidance on the legal and rights framework for artists and arts organisations – see below.

We are living in a society and at a time, when the lived experience of hundreds of thousands of people is becoming unspeakable. Although it doesn’t appear to be the case that Prevent officers are checking out what is going on in our theatres and galleries, the impact of Prevent as a force for pervasive self-censorship across Muslim communities is massive and one of the main free speech issues of the day. This will of course influence what makes its way into our arts venues. Add to that other invasive state surveillance powers, the rolling back of human rights generally, the arts has an ever more important role to play to tackle these issues, to ask the most important questions, to challenge growing authoritarian tendencies; playing safe is not an option.

The sector plays a vital role in providing space for open debate, but as Svetlana Mintcheva, an international arts and censorship experts writes: “That role is threatened if those institutions fail to take on real controversies around difficult and emotionally charged subject matter because some of that subject matter may be offensive or even traumatic. Unless they are prepared to welcome genuine conflict and disagreement, cultural institutions will operate as echo chambers under the pall of a fearful consensus, rather than leaders in a vibrant and agonistic public sphere.”

These are some of the issues that we are grappling with in our training: Rights, Risks & Reputations – Challenging a Risk Averse Culture, aiming to give arts leaders the information they need to take difficult, risky decisions more confidently. They will complement the efforts that many organisations are making, and have been making for decades in some cases, to diversify, by reinforcing the importance of risk and controversy in achieving these aims. To this end, we will be taking a close look at the social importance of risk and controversy and the steps needed to reinforce appetite and capacity for risk-taking; how the powerful complementarity of the rights to freedom of expression and equality gives a useful framework for this work. Looking at issues that could lead to self-censorship – fear of causing offence and/or protest and confusion around new counter-terrorism legislation, we will dig into Index’s legal guides for arts on three legally protected areas of society: Counter-Terrorism, Race and Religion and Public Order; Public Order police trainers will present their perspective on how and when to work with the police around artwork that might generate protest in the public space; and there will be a module on ethical fundraising.

The second part of the Michael Scammells statement quoted above is “freedom of expression...has to be actively maintained by the vigilance of those that care about it”. Freedom of expression is an active stance full of challenges, just like equality – both need to be enacted, not left on the shelf in a policy document. Freedom of expression where everyone agrees is not worth the paper it is written on; it will always include the right to shock, insult and offend. And, coupled with equality, it changes whose stories, imagination, revelations and visions shock, insult and offend even as they inspire, inform and transform.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The first editor of Index on Censorship magazine reflects on the driving forces behind its founding in 1972″ google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]A version of this article first appeared in Index on Censorship magazine in December 1981. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The first issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, 1972

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”My friends and I think it would be very important to create an international committee or council that would make it its purpose to support the democratic movement in the USSR.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Looking back, not only over the thirty years since Index was started, but much further, over the history of our civilisation, one cannot help but realise that censorship is by no means a recent phenomenon.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:%20https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F09%2Ffree-to-air%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/09/free-to-air/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]