Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Frequent visitors to the skatepark on London’s South Bank may have noticed two new works of art among the decades-old graffiti. Both spray-painted in black and white, one image depicts a naked and emaciated mother clutching a newborn; another shows a starving boy, his hair on end, listlessly picking at his hands. Entitled “Hollowed Mother” and “Lost Generation” (pictured), the figures are cadaverous and haunting, with dark empty holes where their eyes should be. Similar works of street art can be found in Hodeida and Sana’a, cities in Yemen: on the wreck of a door, now in a garbage dump, or on the last standing wall of a house reduced to rubble. “Faces of War”, a project by Murad Subay, a Yemeni artist, seeks to draw attention to the worst humanitarian crisis in the world. Read the article in full.

Using stencils and spray paint, Murad Subay creates haunting figures, portraits and motifs. Read the full article.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”74843″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Murad Subay, a Yemeni street artist and the 2016 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Arts Fellow, was rejected for a visa to study at Aix-Marseille University as part of a one-year grant for threatened artists.

Subay, who creates murals protesting against Yemen’s civil war, was given a grant to study under the Institute of International Education’s Artistic Protection Fund, sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which makes fellowship grants to artists from any field of practice, and places them at host institutions in safe countries where they can continue their work and plan for their futures.

The visa that would have allowed Subay to study was rejected by authorities on Friday, he told Index via email.

“This rejection highlights a spreading hostility to artistic freedom around the world. From Uganda to Indonesia to Cuba, proposed legislation threatens to control artists, while a growing number of supposedly democratic countries such as the UK frequently refuse visas to foreign authors, musicians and activists for events or training. This reinforces notion that constraining artistic freedom is acceptable,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship said.

“We ask French authorities to reverse this decision and allow Murad, an Index fellow, to study.”

Subay’s murals grew from the frustration he felt as his homeland descended into chaos and factionalism. Amid the destruction and anger, Subay picked up his brush. He went out into the streets with friends and began painting in broad daylight. After a few days he was joined by people from the community driven by their desire for peace amid Yemen’s civil war.

The Yemeni civil war has been raging since 2015. An estimated 13,600 people have been killed, including more than 5,200 civilians. The strife has contributed to the death of an estimated 50,000 people from an ongoing famine. In 2018, the United Nations warned that 13 million Yemeni civilians face starvation in what it says could become “the worst famine in the world in 100 years.”[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1556538997921-272e591f-f0ed-0″ taxonomies=”8196″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

An anti-war mural created by Yemeni street artist Murad Subay, 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award winner.

Art has been used as a form of protest during times of crisis throughout history. It is a popular and, at times, effective platform to express opinions about societal or governmental problems, particularly when other forms of protest are not available. Protest art includes performances, site-specific installations, graffiti and street art.

Here Index highlights key articles about art and protest from around the world, from the past five decades.

December 1975, vol. 4 issue: 4

Alexander Glezer writes about his participation in organising the unofficial art exhibit in Moscow. When the first exhibition opened, it was bulldozed by undercover police officers and agents from the KGB (Committee for State Security). In the second exhibition, the authorities were forced by the public to grant permission and ten to fifteen thousand people came to see the paintings and sculptures of 50 nonconformist artists’. Glezer, 41-years-old, was questioned by the KGB, arrested and sentenced 10 days for “hooliganism”. He was allowed to leave the Soviet Union in 1975 February.

December 1974, vol. 3 issue: 4

The Sao Mamed Gallery opened with 186 artworks by 87 artists who had never shown their work in public before due to the regime’s dictating of Portuguese life. The gallery was built to celebrate the result of the military coup abolishing censorship of expression.

Published in the New York Times.

September 2012, vol. 41 issue: 3

Malu Halasa, co-curator of the exhibition Culture in Defiance: Continuing Traditions of Satire, Art and the Struggle for Freedom in Syria, writes about how the violence in Syria affected country’s art of resistance production and then created ideas of spreading this work further West which was the reason for the exhibition’s creation.

Dark Arts: Three Uzbek artists speak out on state constraints

December 2014, vol. 43 issue: 4

Author Nargis Tashpulatova interviews writer three Uzbek artists – Sid Yanishev, photographer Umida Akhmedova and conceptual artist Vyacheslav Akhunov who continue to create artwork throughout governmental threats and censorship and the regression of art in Uzbek society.

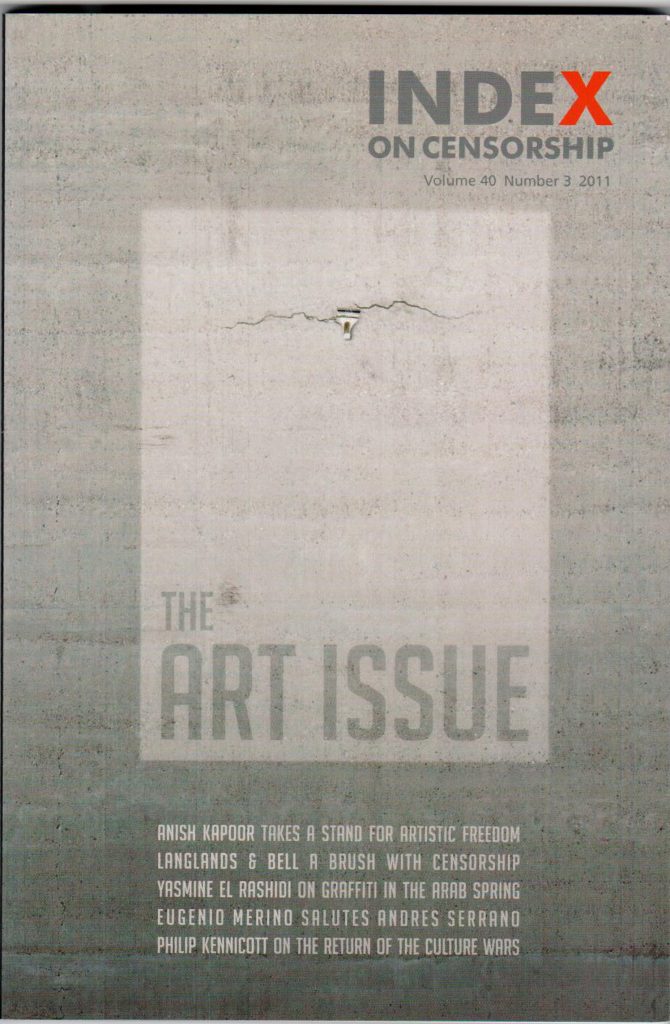

October 2011, vol. 40 issue: 3

Yasmine El Rashidi writes on the outbreak of graffiti in the streets in Cairo during the 18 days of the Egyptian revolution.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1546513460633-7f241be5-ccf1-1″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]