9 Jul 2020 | Campaigns - new test

from Turkey to Poland, Brazil to Kashmir, the most stark has been the appalling attack on human rights in Hong Kong. The Chinese government has dealt a fatal blow to the “one country, two systems” pledge. In the hours that followed the government enacting its new National Security Law for Hong Kong, hundreds of people deleted their social media accounts for fear of arrest. Pro-democracy campaigners have shut up shop in the fear of life imprisonment and journalists on the ground are under huge pressure to curtail their reports.

In spite of the very real threat of arrest, however, thousands of people have taken to the streets to demand their human rights to free association, to free speech and to a life lived without fear of tyranny. Their actions, their bravery and their determination should inspire us all and I’d urge you to read the words of our correspondent from Hong Kong, Tammy Lai-Ming Ho. Events in Hong Kong need to generate more than just a hashtag – we need action from our governments. And we all must stand with Hong Kong.

As events developed in Hong Kong other national leaders were also moving against their populations. On Monday, the Ethiopian musician and activist Haacaaluu Hundeessaa was murdered. Hundeessaa’s music provided the living soundtrack to the protest movement that led to the former prime minister’s resignation. In the hours that followed Hundeessaa’s murder 80 people were killed and the government deployed the military in order to restrict protest and limit access to Hundeessaa’s funeral. They have also switched off access to the internet (again) to stop people telling their stories.

It is easy for us to miss the people behind these events. And in a world where oppression is becoming all too common, sustaining our anger to support one cause when the next outrage is reported can be difficult. But we cannot and will not abandon those who have shown such bravery in the face of brute force and institutional power.

Index was created to be “a voice for the persecuted” and with you we will keep being exactly that. Providing a platform for the voiceless and shining a light on repressive regimes wherever they may be

3 Jul 2020 | China, Ethiopia, Hong Kong, News and features, Opinion

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114148″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Following the news this week has been harrowing. Beyond the ongoing awful deaths from Covid-19 and the daily redundancy notices we also now have some governments turning against their citizens. Free speech around the world, or rather the restrictions on it, have dominated nearly every news cycle and behind each report there have been inspiring personal stories of immense bravery in standing up against repression.

While there have been government orchestrated or sanctioned attacks on free speech across the globe, from Turkey to Poland, Brazil to Kashmir, the most stark has been the appalling attack on human rights in Hong Kong. The Chinese government has dealt a fatal blow to the “one country, two systems” pledge. In the hours that followed the government enacting its new National Security Law for Hong Kong, hundreds of people deleted their social media accounts for fear of arrest. Pro-democracy campaigners have shut up shop in the fear of life imprisonment and journalists on the ground are under huge pressure to curtail their reports.

In spite of the very real threat of arrest, however, thousands of people have taken to the streets to demand their human rights to free association, to free speech and to a life lived without fear of tyranny. Their actions, their bravery and their determination should inspire us all and I’d urge you to read the words of our correspondent from Hong Kong, Tammy Lai-Ming Ho. Events in Hong Kong need to generate more than just a hashtag – we need action from our governments. And we all must stand with Hong Kong.

As events developed in Hong Kong other national leaders were also moving against their populations. On Monday, the Ethiopian musician and activist Haacaaluu Hundeessaa was murdered. Hundeessaa’s music provided the living soundtrack to the protest movement that led to the former prime minister’s resignation. In the hours that followed Hundeessaa’s murder 80 people were killed and the government deployed the military in order to restrict protest and limit access to Hundeessaa’s funeral. They have also switched off access to the internet (again) to stop people telling their stories.

It is easy for us to miss the people behind these events. And in a world where oppression is becoming all too common, sustaining our anger to support one cause when the next outrage is reported can be difficult. But we cannot and will not abandon those who have shown such bravery in the face of brute force and institutional power.

Index was created to be “a voice for the persecuted” and with you we will keep being exactly that. Providing a platform for the voiceless and shining a light on repressive regimes wherever they may be.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Essential reading” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

14 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

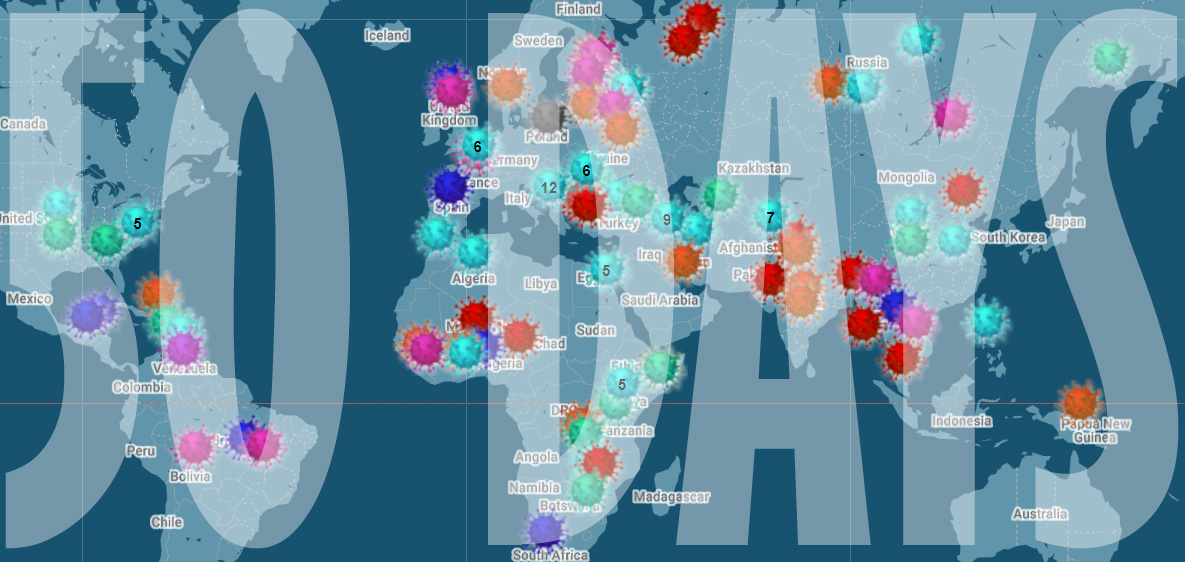

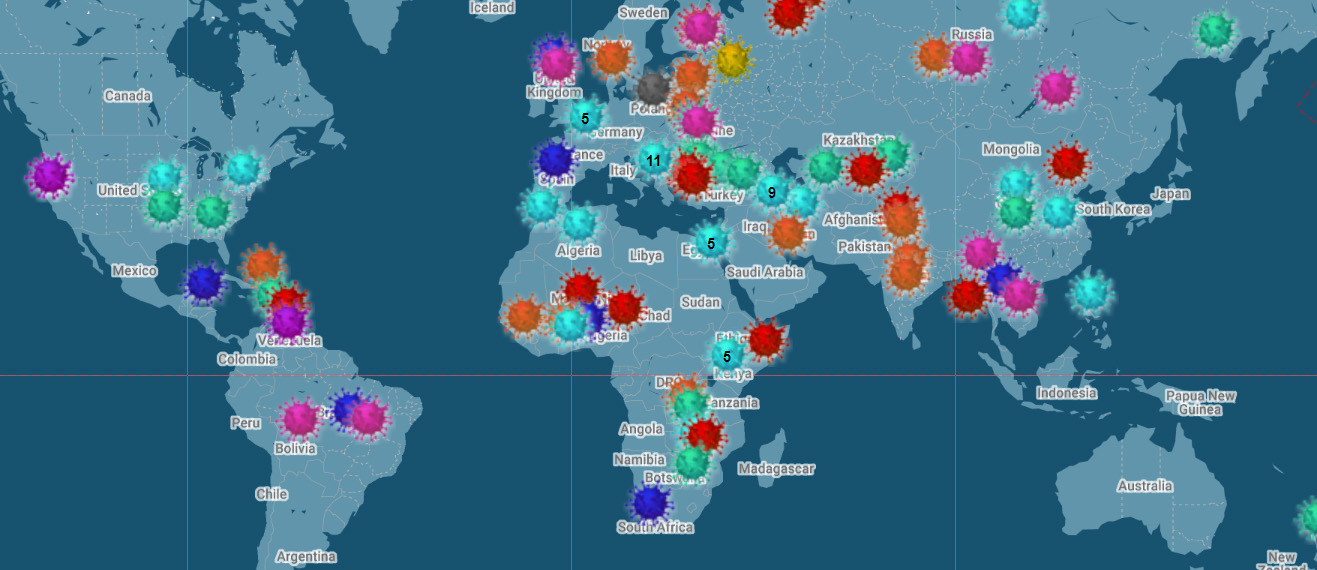

As we mark 50 days since we first started collating attacks on media freedom related to the coronavirus crisis, we’re horrified by the number of attacks we have mapped – over 150 in what is ultimately a short period of time.

We know that in times of crisis media attacks often increase – just look at what happened to journalists after the military coup in Egypt in 2013 and the failed coup against Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey in 2016. The extent of the current attacks, in democratic as well as authoritarian countries, has been a shock.

Our network of readers, correspondents, Index staff and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation have helped collect the more than 150 reports media attacks.

But these incidents are likely to be the very tip of the iceberg. When the world is in lockdown, finding out about abuses of power is harder than ever. Journalists are struggling to do their job even before harassment. How many more attacks are happening that we don’t yet know about? It’s a scary thought.

Rachael Jolley, editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship, said: “We are alarmed at the ferocity of some of the attacks on media freedom we are seeing being unveiled. In some states journalists are threatened with prison sentences for reporting on shortages of vital hospital equipment. The public need to know this kind of life-saving information, not have it kept from them. Our reporting is highlighting that governments around the world are tempted to use different tactics to stop the public knowing what they need to know.”

Index is alarmed that the attacks are not coming from the usual suspects. Yes, there have been plenty of incidents reported in Russia and the former Soviet Union, Turkey, Hungary and Brazil. At the same time there have been many incidents in countries you would not expect to see – Spain, New Zealand, Germany and the UK.

The most common incident we have recorded on the map are attacks on journalists – whether physical or verbal – and cases where reporters have been detained or arrested. There have been more than 30 attacks on journalists, with the source of many of these being the US President Donald Trump. He has a history of being combative with the press and decrying fake news even where the opposite is the case and the crisis has seen a ramped up attempt at excluding the media. During the crisis, he has refused to answer journalists’ questions, attacked the credentials of reporters and walked out from press conferences when he doesn’t like the direction they are taking.

We have also seen reporters and broadcasters detained and charged just for trying to tell the story of the crisis, including Dhaval Patel, editor of the online news portal Face of Nation in Gujarat, Mushtaq Ahmed in Bangladesh and award-winning investigative journalist Wan Noor Hayati Wan Alias in Malaysia.

Since we started the mapping project, we have highlighted other specific trends. Orna Herr has written about how coronavirus is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims. Jemimah Steinfeld wrote about how certain leaders are dodging questions while we have also looked at how freedom of information laws are being suspended or deadlines for information extended.

Although the map does not tell the whole story it does act as a record of these attacks. When this crisis is finally all over, it will allow us to ask questions about why these attacks happened and to make sure that any restrictions that have been introduced are reversed, giving us back our freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_btn title=”Report an incident” shape=”round” color=”danger” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fforms.gle%2Fhptj5F6ZvxjcaGLa7|||” css=”.vc_custom_1589455005016{border-radius: 5px !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

1 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Governments are using the Covid-19 crisis to change freedom of information laws and, unless we are very careful, important stories could get unreported. Since the beginning of the crisis, governments from Brazil to Scotland have made changes to their FOI laws; some of the changes are rooted in pragmatism at this unprecedented time; others may be inspired by more sinister motives.

FOI laws are a vital part of the toolkit of the free media and form a strong pillar that supports the functioning of open societies.

According to a 2019 report by Unesco – published some two and a half centuries after the first such law was introduced in Sweden – 126 countries around the world now have freedom of information laws. These typically allow journalists and the general public the right to request information relating to decisions made by public bodies and insight into administration of those public bodies.

US president Thomas Jefferson once wrote: “Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights.”

Now in this time of crisis, freedom of information processes are being shut down, denied unless they relate specifically to the crisis or the deadlines for responses are being extended.

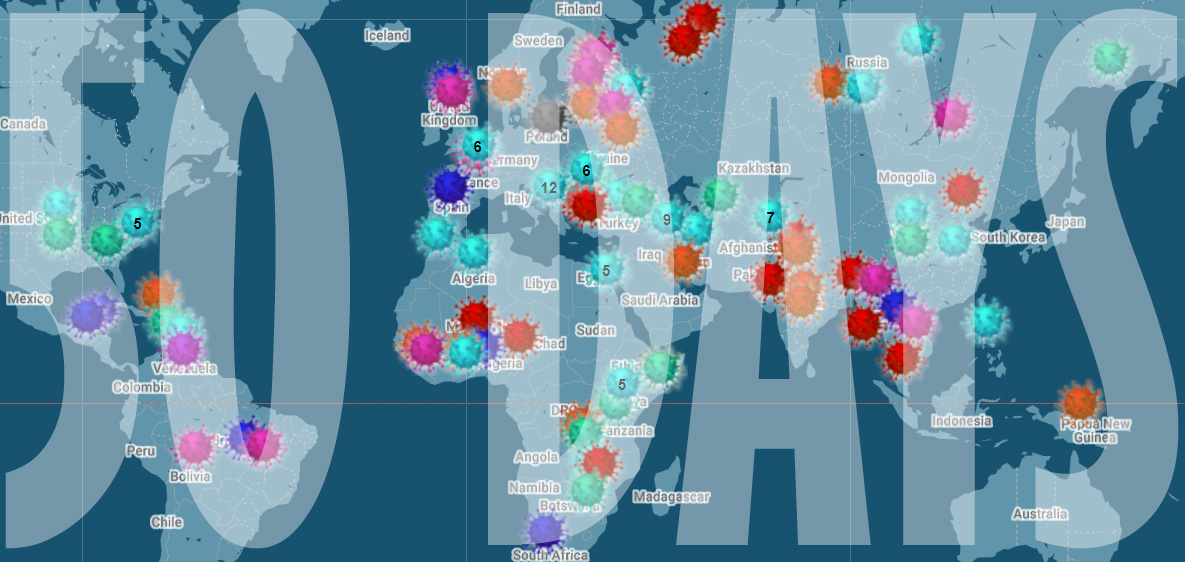

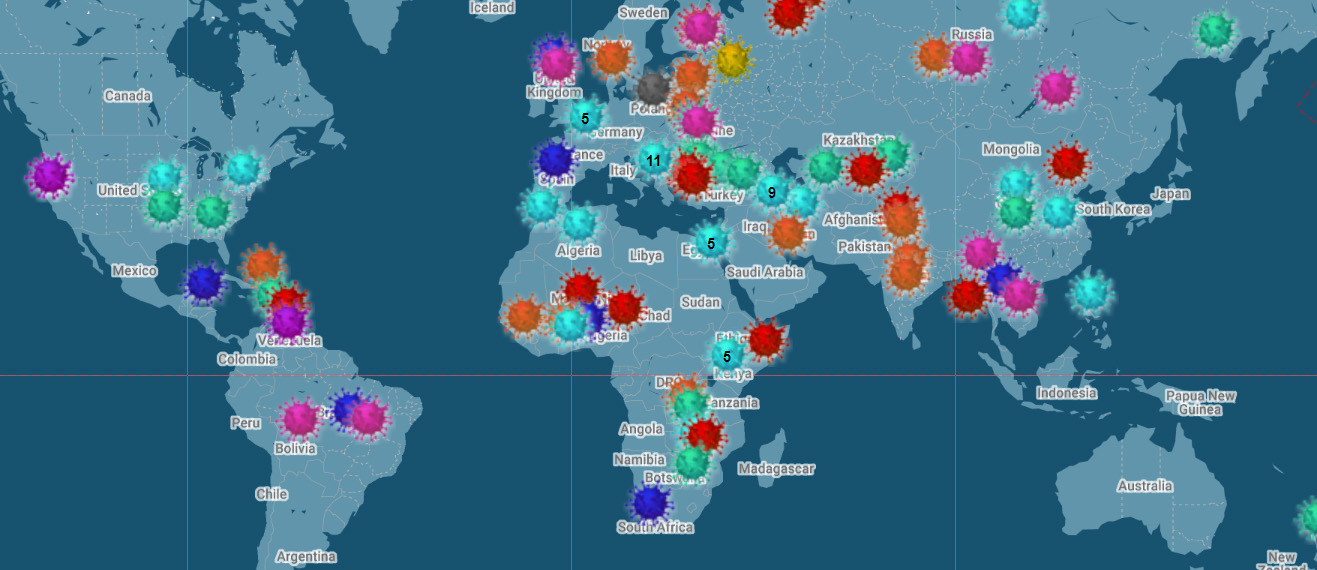

When the Covid-19 crisis first erupted, we made a decision to monitor attacks on media freedom. It wasn’t just a random idea; we know that in similar times of crisis, repressive governments often attack the work that journalists do – sometimes the journalists themselves – or introduce new legislation they have wanted to do for some time and now see a time of crisis as an opportunity to do so without proper scrutiny.

Since the start of the crisis, we have been collecting reports on attacks on media freedom through an innovative, interactive map. More than 125 incidents have been reported by our readers, our network of international correspondents, our staff in the UK and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation. Many relate to changes to FOI legislation.

Let us be clear there can be legitimate reasons for amending legislation in times of international crisis. With many public officials forced to work from home, many do not have access to the information they need or the colleagues they need to consult to be able to answer journalists’ requests. Others need more time to be able to put together an informed response.

Yet both restrictions and delays are worrying. They allow politicians and public bodies to sweep information that should be freely available and subject to wider scrutiny under the carpet of coronavirus. News that is three months old is, very often, no longer news.

In its Coronavirus (Scotland) Bill, the Scottish government has agreed temporary changes to the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 that extend the deadlines for getting response to information requests from 20 to 60 working days. The initial draft wording sought to allow some agencies to extend this deadline by a further 40 days “where an authority was not able to respond to a request due to the volume and complexity of the information request or the overall number of requests being dealt with by the authority”. However, this was removed during the reading of the bill following concerns raised by the Scottish information commissioner.

The bill was passed unanimously on 1 April and became law on 6 April. As it stands the new regulations remain in force until 30 September 2020 but can be extended twice by a further six months.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro has issued a provisional measure which means that the government no longer has to answer freedom of information requests within the usual deadline. Marcelo Träsel of the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism says the measure is “dangerous” as it gives scope for discretion in responding to requests.

The decree compelled 70 organisations to sign a statement requesting the government not to make the requested changes, saying “we will only win the pandemic with transparency”.

Romania and El Salvador are among the other countries which have stopped FOI requests or extended deadlines. By contrast, countries such as New Zealand have reocgnised the importance of FOI even in a crisis. The NZ minister of justice Andrew Little tweeted: “The Official Information Act remains important for holding power to account during this extraordinary time.”

FOI law changes are not the only trends we have noticed.

Index’s deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld has noted how world leaders are ducking questions on coronavirus while editorial assistant Orna Herr has written about how the crisis is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims.

If you are a journalist facing unreasonable delays in receiving information from public bodies at this time, do report it to us at bit.ly/reportcorona.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]