1 Feb 2023 | Iran, News and features

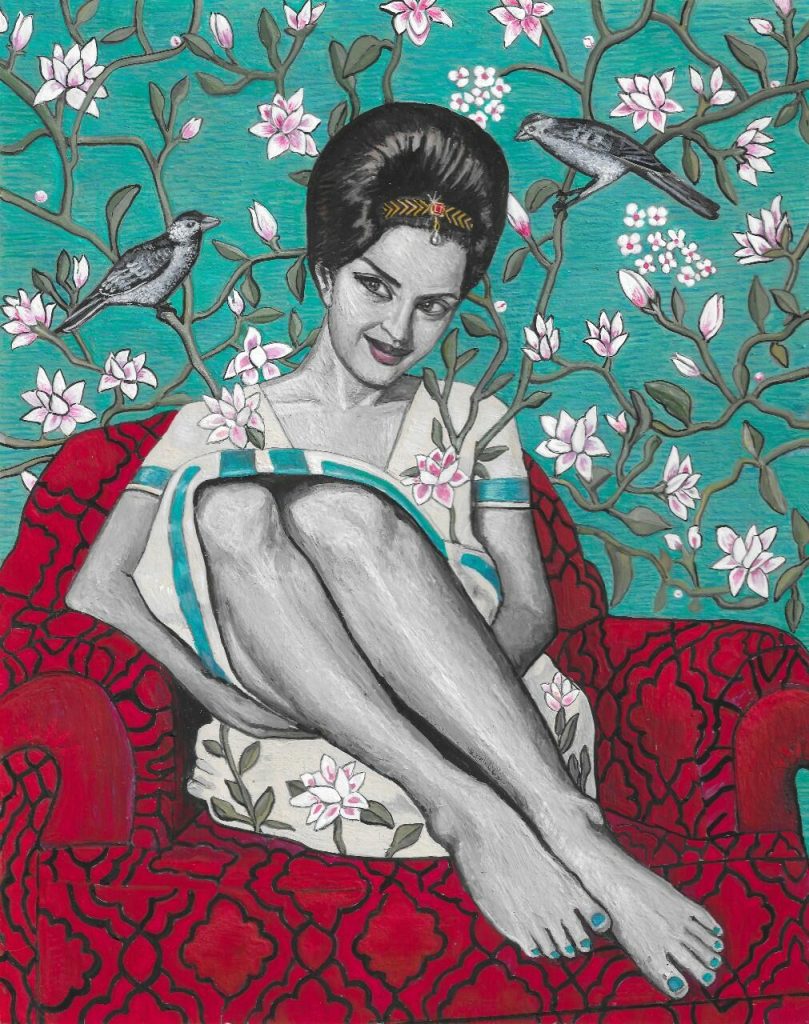

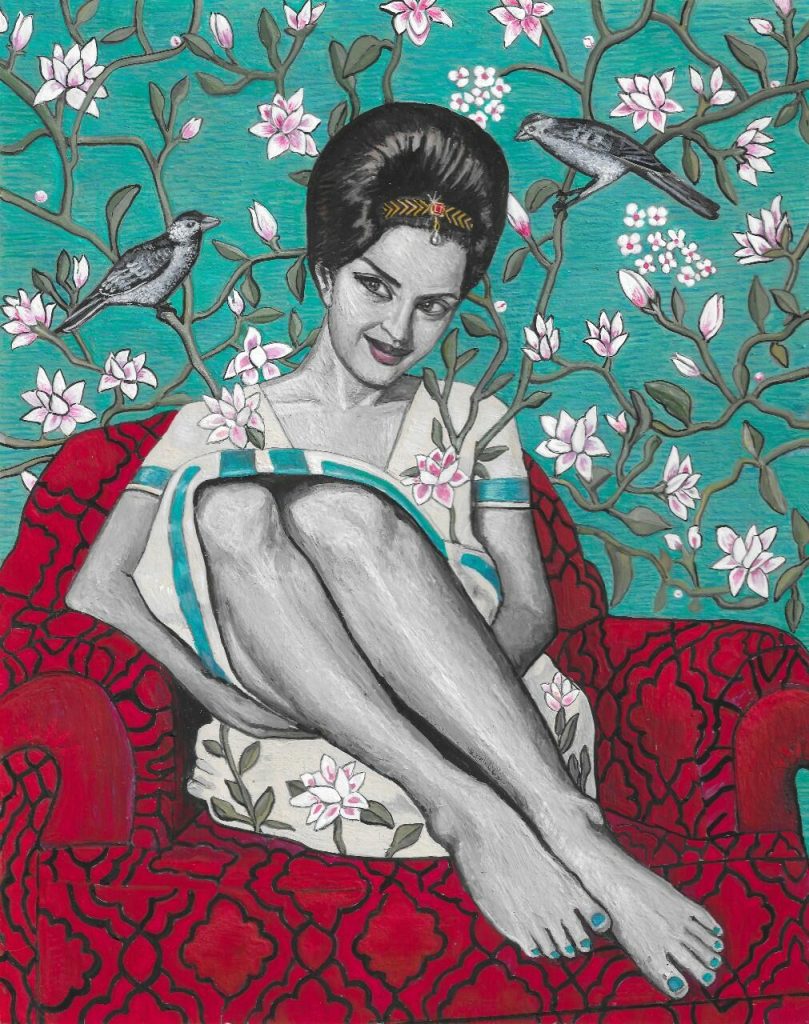

Wild at Heart (Portrait of Pouran Shapoori), 2019 Credit: Soheila Sokhanvari, courtesy Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

The long, winding path of The Curve art gallery at London’s Barbican Centre has been transformed into a devotional space. The cavernous room is dimly lit and echoes with the calming voices of female Iranian singers. Sprawling, Islamic, geometric patterns roll down the tall walls which are splintered with the light projected onto them by dazzling mirrored sculptures. Apart from the female voices, it feels like a mosque.

Take a closer look, and the walls are scattered with traditional Persian miniatures, depicting women whose histories have been erased in Iran. In painstaking detail, Soheila Sokhanvari’s portraits provide a snapshot into women’s lives pre-revolution. Born in Shiraz in the Fars Province of Iran, she came to England in 1978, just a year before the Islamic Revolution. But Sokhanvari remains enchanted with the country she left behind. Her miniatures depict unveiled and glamorous women, creative dissidents who pursued careers in a country awash with Western style but not its freedoms.

“I can relate directly to the women in my paintings,” she told Index. “Like them I am an artist but, unlike them, I am able to pursue my career, wear what I want and act as I want, and the idea that one day someone could take my freedom away from me is unthinkable”.

The portraits are displayed without names or biographical info but, by scanning a QR code, we are guided through the exhibition by their stories. There are 28 in total: actors, singers, poets, writers, dancers and film directors, all of which were either forced into silence or exile in 1979, when the Islamic Revolution led to a rollback in women’s legal rights. Much of their work is censored in Iran today. “I knew of many of the women from my own experience and time in Iran as a young girl,” Sokhanvari explained. “They were my idols, but finding out more information about the lives of several of the women took lots of research – they were essentially erased from the record by the regime”. She said that a small number of the women – like singer and actress Googoosh – are very famous, but that several had tragically died too young and were hard to trace.

The exhibition draws the spotlight back onto these talented women for which, she says, she feels a deep loss. The portraits beautifully capture this feeling: a simultaneous celebration of their bravery and a mourning of their freedoms. Vivid patterns and clothing contrast monochromatic faces, which make the pictures feel both vibrant and ghostly. The use of new and old multimedia was significant in telling these stories too. “I painted my portraits in the ancient technique of egg tempera, onto calf vellum, and I included films in which the women starred, ” Sokhanvari said. Two holograms of dancing Iranian actors Kobra Saeedi and Jamileh are also hidden in boxes. “I wanted the viewers to see these women, to watch them dance and to hear them sing, since they have been banned from these platforms.” The broadcasting of women’s voices in public is illegal in Iran. “I wanted to show these women at the height of their creativity, to show them as the sensational artists that they are, and using multimedia helped to achieve this immersive experience.”

This contrast of old and new is fitting. While the exhibition was curated without sight of the current unrest in Iran, the portraits certainly gain a tragic poignancy because of it. The brave women of Sokhanvari’s portraits embody much of what people are fighting for today. “Young women are at the front of this revolution and that is what gives it its power,” she told Index. “I feel a new sense of positivity and hope that perhaps we will see the end of this regime, but simultaneously I feel pain and bitterness that it is at the cost of so many bright lives.”

Although she doesn’t describe her artwork as a protest, she says that the message is political.

“What is happening in Iran can no longer be seen as just another protest, it is a revolution and I stand in solidarity with my sisters.” I asked if her portraits reflect a lost past or a hopeful future. She says both.

‘Rebel Rebel’ at The Curve, Barbican is open until 26 February 2023

25 Jan 2023 | FEATURED: Jemimah Steinfield, News and features

In the aftermath of her murder in 2017, the family of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia found themselves embroiled in a nasty battle with a London law firm. Dubbed a “one-woman Wikileaks” for her exposures of corruption among Malta’s elite Caruana Galizia had faced 42 civil libel cases and five criminal libel cases while alive. These cases passed posthumously to her family. One of them came from a company that had headquarters in London, meaning they could bring legal action there.

“It was like falling further into a pit,” her son Matthew told me over the phone from Malta. “I never imagined I’d be battling these [legal threats]. Everything that could happen to make the situation worse did happen,” he said.

The UK’s libel laws are notoriously open to abuse (as was reported by openDemocracy yesterday) – and London law firms have been at the beck and call of the powerful worldwide. Cases like Caruana Galizia’s have a name – SLAPPs. An acronym for “strategic lawsuits against public participation”, these heavy-handed legal actions seek to intimidate and deter journalists. Their purpose is not to address genuine grievances but to drain targets of as much time, money and energy as possible in an effort to silence them – and to dissuade other journalists from similar investigations.

The laws are also known to be claimant-friendly, especially those in England and Wales where the burden of proof required from a publisher is enormous, often impossible, effectively meaning the accused is guilty until proven innocent. It’s this quirk, combined with exorbitant fees for both parties, which has made London a SLAPPs breeding ground. A 2020 survey of reporters across 41 countries found the UK was the source of 31% of legal threats against journalists. The USA, by contrast, accounted for 11%, and all EU countries combined for 24%.

But the loopholes in UK law might be closing, finally starving firms that have grown fat on oligarchs’ money. A set of reforms were announced last summer that seek to limit the impact of SLAPPs. The reforms are twofold: first, stop cases before they get to court through a series of tests. Do they go against activity in the public interest, for example? If so, throw them out. Next, cap fees for those cases that do make it through.

Half a year on we are still waiting for reforms that, frankly, can’t come fast enough. SLAPPs have long cast a dark shadow over the UK’s media and publishing landscape. 2022 alone saw the climax of big legal actions against Guardian and Observer journalist Carole Cadwalladr, who was taken to court by multimillionaire Brexit backer Arron Banks as a result of a comment she made on a TEDTalk in Canada, FT journalist Tom Burgis, author of Kleptopia: How Dirty Money is Conquering the World, which led to defamation charges by Kazakh mining giant ENRC, and former Reuters journalist Catherine Belton, who was sued over a number of matters in her book Putin’s People: How the KGB took back Russia and then took on the west, by multiple Russian billionaires, including Roman Abramovich.

Neither Burgis’ nor Belton’s cases made it to a full trial. Burgis’ was dismissed by a judge, while Belton settled after revisions were made to her book. Cadwalladr was less lucky. A trial at London’s High Court took place. At the time she said she feared losing her home and bankruptcy. She managed to crowdfund nearly £600,000 to cover costs, and the judgement ruled in her favour in June (although Banks has since been granted permission to appeal).

Yet even these victories are Pyrrhic ones. In a testimony given in the UK’s House of Commons after his case was dropped, Burgis said: “There is money that will not be got back that could have been spent on other books.”

He added:

“There is always a danger, as I know from conversations with colleagues, that you become an expensive and problematic journalist. In an era when the newspaper business model remains broke and oligarchs are amassing more and more wealth, this inequality of arms is extraordinary.”

Out of the spotlight plenty more battle away, ones with far less funding and backing. Journalists at Swedish business and finance publication Realtid, for example, were recently sued in London in connection with their investigation into the financing of energy projects involving a Swedish businessman. Faced with the prospect of financial ruin, just last week, on 13 January, it was announced that they had settled out of court, on condition that they published an apology.

It’s not just the personal toll on these journalists that is deeply concerning; it’s the industry-wide cost. Fear of legal threats is as damning as the threats themselves. Like the guillotine in revolutionary France, it hovers overhead. Do you meet with the whistleblower whose story might land you a Pulitzer, but also might land you in court? I’ve spoken to editors at desks who have become too scared to touch certain topics; a single strongly-worded letter from a minted London law firm is all it takes to spike an article. A top journalist in the UK, now in his 60s who has reported all over the world, told me that he’s never operated in a more fearful media environment than this. Covering your back is exhausting and the risk of humiliation high too. It demands nerves of steel and a sizeable chunk of liability insurance to boot. Young journalists, small media outfits and freelancers are basically counted out.

How many stories have never seen the light and what information are British readers being deprived of? Speaking at a House of Lords Committee back in April, Thomas Jarvis, legal director at Harper Collins, said the publisher regularly avoids publishing information in books in the UK that would be included in international editions because “the risk of publication in the UK is far greater”. This came from the publisher behind both Belton and Burgis’ books, with a proven record to take risks.

Burgis told me that he feels “incredibly lucky to have been backed so bravely” by his publishers. At the same time he’s angry about “all the information of vital public interest that gets suppressed because there is often today such inequality of arms between journalists (incredibly poor) and the powerful (increasingly rich).”

There’s now a real opportunity for change. The war in Ukraine catapulted SLAPPs to the forefront. With some cases being brought by oligarchs and kleptocrats with links to Putin, there has never been a less fashionable time to be a claimant. The UK also has a new head of state and a new prime minister. What better way to show their commitment to democracy than by closing the legal loopholes.

The tide has been turning against SLAPPs for some time. In early 2021, the UK Anti-SLAPP Coalition emerged, made up of NGOs, individual campaigners and lawyers, co-founded and led by Index. It helped pave the wave for the proposed legislation. Through the coalition’s efforts and a changing international landscape British MPs have started to take SLAPPs seriously. So why not push this legislation across the finish line? Today it stubbornly remains just a proposal, rather than a reality. And, speaking to Gill Phillips, director of editorial legal services at the Guardian, she confirmed some of my fears if it does get passed – namely the devil will be in the detail – and the detail has yet to be finessed. No “definition” of public interest, for example, has been provided. Nor is there a clear definition of what constitutes a SLAPP. This might appear like semantics, but in the case of Cadwalladr the judge didn’t deem the case as SLAPP, a judgment that perplexed many.

Still, all those involved in the Coalition welcomed the proposals when they were first mooted, as did Matthew Caruana Galizia.

“What the government is doing is putting a flag up a pole” he said. He thinks the proposals are good and if passed will improve the situation. He adds though that “we can go further”.

“I say ‘we’ not as a UK citizen – I’m a citizen of Malta – but ‘we’ because ‘we’ all suffer as a result of what the British courts allow. They’ve become a platform to stop investigative journalism.”

Let’s dismantle this platform in 2023. It’s high time to end the trial of media freedom.

25 Jan 2023 | Australia, Austria, Bahrain, Belarus, Belgium, Botswana, Burma, China, Cuba, Czech Republic, Denmark, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Index Index, Ireland, Laos, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Netherlands, News and features, Nicaragua, North Korea, Norway, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Sudan, Swaziland, Switzerland, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, United States, Yemen

A major new global ranking index tracking the state of free expression published today (Wednesday, 25 January) by Index on Censorship sees the UK ranked as only “partially open” in every key area measured.

In the overall rankings, the UK fell below countries including Australia, Israel, Costa Rica, Chile, Jamaica and Japan. European neighbours such as Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Denmark also all rank higher than the UK.

The Index Index, developed by Index on Censorship and experts in machine learning and journalism at Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU), uses innovative machine learning techniques to map the free expression landscape across the globe, giving a country-by-country view of the state of free expression across academic, digital and media/press freedoms.

Key findings include:

-

The countries with the highest ranking (“open”) on the overall Index are clustered around western Europe and Australasia – Australia, Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland.

-

The UK and USA join countries such as Botswana, Czechia, Greece, Moldova, Panama, Romania, South Africa and Tunisia ranked as “partially open”.

-

The poorest performing countries across all metrics, ranked as “closed”, are Bahrain, Belarus, Burma/Myanmar, China, Cuba, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Laos, Nicaragua, North Korea, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

-

Countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates performed poorly in the Index Index but are embedded in key international mechanisms including G20 and the UN Security Council.

Ruth Anderson, Index on Censorship CEO, said:

“The launch of the new Index Index is a landmark moment in how we track freedom of expression in key areas across the world. Index on Censorship and the team at Liverpool John Moores University have developed a rankings system that provides a unique insight into the freedom of expression landscape in every country for which data is available.

“The findings of the pilot project are illuminating, surprising and concerning in equal measure. The United Kingdom ranking may well raise some eyebrows, though is not entirely unexpected. Index on Censorship’s recent work on issues as diverse as Chinese Communist Party influence in the art world through to the chilling effect of the UK Government’s Online Safety Bill all point to backward steps for a country that has long viewed itself as a bastion of freedom of expression.

“On a global scale, the Index Index shines a light once again on those countries such as China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates with considerable influence on international bodies and mechanisms – but with barely any protections for freedom of expression across the digital, academic and media spheres.”

Nik Williams, Index on Censorship policy and campaigns officer, said:

“With global threats to free expression growing, developing an accurate country-by-country view of threats to academic, digital and media freedom is the first necessary step towards identifying what needs to change. With gaps in current data sets, it is hoped that future ‘Index Index’ rankings will have further country-level data that can be verified and shared with partners and policy-makers.

“As the ‘Index Index’ grows and develops beyond this pilot year, it will not only map threats to free expression but also where we need to focus our efforts to ensure that academics, artists, writers, journalists, campaigners and civil society do not suffer in silence.”

Steve Harrison, LJMU senior lecturer in journalism, said:

“Journalists need credible and authoritative sources of information to counter the glut of dis-information and downright untruths which we’re being bombarded with these days. The Index Index is one such source, and LJMU is proud to have played our part in developing it.

“We hope it becomes a useful tool for journalists investigating censorship, as well as a learning resource for students. Journalism has been defined as providing information someone, somewhere wants suppressed – the Index Index goes some way to living up to that definition.”

17 Jan 2023 | Crown Confidential, News and features, Volume 51.04 Winter 2022

If you want to understand how deep the UK Royal Family’s mania for secrecy runs, just try the following exercise. Go to the website of the National Archives (anyone with a computer and an internet connection can do this) and search the catalogue with the term “Royal Family”. It is then possible to filter the search to see which files are “closed” or “retained”. Nearly 500 files are categorised in this way, some going back well into the last century, beyond the reign of the late Queen Elizabeth Il’s father, George VI.

Perhaps not surprisingly, hundreds of these files refer to the short reign of her uncle, Edwiard VIII, who abdicated in 1936 after less than a year on the throne. Take a closer look and many of these files have absolutely nothing to do with national security, diplomacy or privacy – the usual reasons for withholding government files. In fact, many of them refer to royal memorabilia for Edward’s abandoned coronation, which had been due to take place in May 1937. Embarrassing, perhaps, and the Duke of Windsor, as Edward became, remains a controversial figure. But is it really necessary to keep these files sealed for 100 years?

At a stretch, it is possible to imagine the sensitivity of a file about the “Royal Crown and Cypher on pocket watches from Germany”, given who was in power in that country at the time, but it’s hard to see why files on similar souvenir items manufactured in Britain such as pens, picture frames, neon signs and wine labels should remain secret 86 years later, let alone closed until 2037.

Other entries are just plain bizarre. A file from 1990-91 is marked closed until 2034. Its title is intriguing: “Petition to the Queen on behalf of Ago Piero Ajano aka HRH Don Juan Alexander Fernando Alphonso of Spain concerning his alleged plight of poverty and ill-treatment in the UK.”

It seems Mr Ajano claimed to be the illegitimate son of the Duke of Windsor, and had fallen on hard times. The story is either entirely spurious or utterly sensational: either way, there can be no possible justification for keeping the file secret.

Black spider memos

Since 2010, there has been a blanket exemption to the Freedom of Information Act for all official correspondence relating to the monarch, the heir to the throne and the second-in-line to the throne. This was introduced during the decade-long battle by Guardian journalist Rob Evans to gain access to the so-called “black spider memos” from Prince Charles to certain government departments. Evans argued this correspondence constituted lobbying and should be released in the public interest.

“With the black spider memos, Charles was lobbying and trying to influence public policy,” Evans told Index. “We ought to know about this just as we would if it was a pharmaceutical company.”

Evans believes his experience with the memos revealed a wider issue with transparency: “The reality is that the government wraps the royal family in secrecy in order to protect it from criticism. Whatever you think about the royal family, democracy is degraded because we can’t debate this fully if we don’t have all the information.”

After the death of Elizabeth II on 8 September 2022, two contradictory narratives about her historical legacy came to dominate the instant analysis of her 70-year reign. The first was that she assiduously took a back seat in matters of state and adopted a largely passive constitutional role. The second was that she was instrumental in guiding the country in the post-war period from Empire to Commonwealth. Neither can be entirely true.

Professor Rory Cormac, of the University of Nottingham and co-author of The Secret Royals, says the narrative of non-interference worked powerfully alongside the pageantry associated with the Queen to produce a benign public image of the monarch. But this is a long way from reality.

“She was a political actor and there are consequences. The idea that all she did was cut a ribbon from time to time is a grotesque misrepresentation. They have managed their past incredibly effectively.”

What the Queen knew

Cormac points to three specific areas where more openness would contribute to a greater understanding of the history of the latter half of the 20th century. The first is the Suez Crisis of 1956, just four years into the Queen’s reign, when Britain was forced into a humiliating retreat by the USA after initially backing the invasion of Egypt to seize back control of the Suez Canal.

“There is a whole cottage industry on what the Queen knew, and when,” said Cormac. “It is a very important case, but historians are just scratching the surface. It’s mainly speculation.”

The second area is the role played by the monarchy in the end of the empire. Many files in the National Archives referring to royal visits to the former colonies during this period are still closed.

The third, crucially important, subject is Northern Ireland, where the Queen’s political role has been largely unexplored by historians. Cormac highlights the example of the royal visit to the province in 1977 – until that point the largest security operation in British history. Files from the government exist, but nothing from the royal side, leaving historians only to speculate.

Cormac and his co-author, Professor Richard Aldrich of Warwick University, are both specialists in the history of intelligence, and the comparison between the royal world and the world of espionage does not go unnoticed in their book:

“Both control and curate their own histories carefully; both are exempt from freedom of information requests. Historians have to wait a long time for intelligence files to make their way to the National Archives – but at least some do eventually arrive. The Royal Family, by contrast, are the real enemies of history. There is no area where restrictions and redactions are so severe.”

Historical vandalism

Cormac is part of a group of historians who believe there needs to be a new approach to royal secrecy. “The argument is that it is a slippery slope,” he said. “There is a blanket ban because, they say, where do you draw the line? But this general exemption needs to be challenged.”

He and Aldrich have identified a process of historical vandalism carried out by loyal royal flunkeys. Lord Louis Mountbatten and art historian and spy Anthony Blunt went on “raiding parties” across Europe in the post-war period searching for documents on the Windsors. Princess Margaret was notorious for the bonfires she made of her mother’s papers. Much else was lost, destroyed or locked away in Windsor Castle.

There is even a file from 1979-80 in the National Archives marked “Royal Family. Duke of Windsor’s Papers: allegations by Duc de Grantmesnil that they were stolen by secret agents”. It is closed.

In a recent essay entitled Queen Elizabeth and the Commonwealth: Time to Open the Archives, Philip Murphy, director of history and policy at the Institute of Historical Research, said: “Its obsessive secrecy combined with the length of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II means we probably have no more accurate a sense of how the monarchy has operated in our lifetimes than our grandparents and great-grandparents did in theirs.”

As Murphy and others point out, the reach of vetting teams from the Cabinet Office who have charge of what should and shouldn’t be published spreads way beyond the National Archives themselves. The personal archives of past prime ministers (Anthony Eden at the University of Birmingham and Harold Macmillan in Oxford) are subject to restrictions on royal material.

Meanwhile, the royal archives at Windsor give no access whatsoever to files on the reign of Elizabeth II, which include correspondence not just with prime ministers of the UK but premiers and governors-general of the Commonwealth realms. Even historians wishing to gain access to files from previous reigns are obliged to sign a form to say they will inform Buckingham Palace how any material will be used. Cameras are forbidden.

There are also files which have been reclassified after historians found information that proved uncomfortable to the Royal Family. A Metropolitan Police file (MEPO 10/35) on the protection arrangements for the Prince of Wales from 1935 showed that his security detail was spying on the future king and his lover Wallis Simpson. Details of Simpson’s affair with a married man, Guy Trundle, are laid out in salacious detail. A note on the affair to the Metropolitan Police commissioner marked “secret” was first released in 2003 and details of the file’s contents featured in Portillo’s State Secrets, a BBC series on the National Archives fronted by the former politician Michael Portillo. Yet any historian attempting to access MEPO 10/35 today will find it is “closed whilst access is under review”. No further explanation is given.

Murphy told Index: “The Palace has an instinct to micromanage and use deference.” In this case, this instinct seems particularly petty-minded as the information is already in the public domain. Most historians interested in the period will already have electronic versions of the file. The note on Simpson’s affair with Trundle is published in all its juicy detail on the website of the National Archives. Portillo’s programme is available to anyone with access to YouTube.

Affairs with film stars

In some cases, the royal fetish for secrecy has left serious gaps in the historical record. For instance, why is so little of detail known about Prince George, Duke of Kent, the youngest brother of Edward VIII and George VI? He was a fascinating and controversial figure – a bisexual playboy who is alleged to have had affairs with film stars and celebrities from the jazz age including Noel Coward. In 1942, George died in an air crash in Scotland while serving in the RAF. He was the only member of the Royal Family for many centuries to have died on active duty. The notes from the Court of Inquiry into the incident were immediately lost and the circumstances of the crash remain shrouded in mystery. The incident is significant because there have been suggestions that the prince flouted wartime regulations to carry out the mission.

In the early 2000s, a veteran royal writer began a project to write George’s biography, but his mission was immediately hampered by the lack of information in the official record. He told Index: “I first visited the National Archives at Kew but Kent’s file, when I ordered it up, had quite obviously been weeded.” The author wrote to the Royal Archives in Windsor only to be informed that there were many calls on the time of the keepers of the records and that on this occasion they would be unable to oblige. He has since given up on the idea of writing the biography and the full life story of Prince George remains untold.

“A family which relies on public support to retain its primacy in British social life has, I believe, a duty to act responsibly when it comes to breaking the law, especially during wartime,” he said. “The actions of the Royal Archives in disallowing me access to Kent’s files (which in any case, it’s my certain belief, would have been severely edited) amounts to censorship, nothing more or less.”

In order to maintain good relations with Buckingham Palace, the author does not wish to be named here, but he remains furious at the lack of openness: “My belief is that everyone is entitled to a certain measure of privacy, but there can be no question that the Royal Family, and those who surround them, ruthlessly seek to rewrite history to their own advantage.”

The writer cites an extraordinary example from the time of the abdication crisis. In government papers from the time, he discovered considerable concern that “Bertie” (the future George VI) was not up to the job of taking over from Edward VIII. Instead, the idea was floated that Queen Mary should become Regent while the dust settled, and the crown would then pass to Prince George. Had this happened, the present Duke of Kent would now be King and not Charles III.

“How the Royal Family manages their affairs in such circumstances is of great importance to historians and, it can be argued, to the nation,” the writer added. “But without access to the Palace papers no accurate record of this event has been written and it’s altogether been bypassed by historians.”

Refused access

As part of Index’s investigation into royal secrecy, we sent a survey to two dozen journalists and historians who specialise in the area. Of those who responded, all but one said their research had been affected by the refusal of the archives to grant access to key materials.

A handful of historians have chosen to fight back. Most prominent of these is Andrew Lownie, the biographer of Edward and Mrs Simpson and the Mountbattens (see article on p.57). For four years, at great personal expense, Lownie has been pushing for the release of the diaries and personal correspondence of Lord Louis Mountbatten, the late Prince Philip’s uncle and mentor to the present king. While these were bought by the University of Southampton using £4.5 million of public money, full public access was blocked at every stage – first by the university and then by an exceptional ministerial directive from the Cabinet Office.

Following intervention from the Information Commissioner’s Office, the files were finally released earlier this year, but costs were not awarded to Lownie, who spent more than £300,000 of his own money on the case. It was, in short, only a half victory and a battle that should never have been fought to start with.

In a more clear-cut victory, Professor Jenny Hocking, of Monash University in Melbourne, successfully challenged the National Archives of Australia to release correspondence between the Queen and the Australian Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, from 1975 (see article on p.59). In that year Kerr dismissed the Labor prime minister Gough Whitlam following a constitutional crisis in which the opposition blocked government business by its control of the upper house of parliament, the Senate. The publication of Hocking’s The Palace Letters show the Queen was in regular correspondence with the governor-general about the possibility of Gough’s dismissal for several weeks. They present a picture of political engagement by the monarch which is very different from the approach the Palace prefers to project.

The work of Lownie and Hocking demonstrates that it is possible to push back against the official wall of silence. But it also shows the lengths to which the establishment is prepared to go to maintain royal secrecy. The Australian National Archives spent $1.7 million of public money contesting the release of the “Palace Letters” and it is not known how much the UK government spent fighting the Mountbatten release – but it is likely to be a similar sum.

There is no evidence that King Charles has a more open attitude to royal history than his mother did. Indeed, he has every reason to keep the papers from the Queen’s reign that refer to his own indiscretions securely locked away in Windsor Castle.

However, despite official efforts, the edifice of secrecy is crumbling. As historians of the Commonwealth further investigate the UK’s colonial past, it is unlikely the Palace will be able to maintain its tight control of the historical narrative in the way it has done in the UK itself. As Philip Murphy has written: “This sort of push-back against the Royal Family’s obsession with secrecy is more likely to be effective outside the UK than in Britain itself, where the Palace still exerts considerable influence over a distinctly deferential political class.”

The legacy of imperialism is the Achilles heel of royal secrecy. It will become increasingly difficult for the Palace to maintain the narrative about the role of the Queen in the successful transition from Empire to Commonwealth without allowing access to the documentary evidence to prove it.