6 Aug 2021 | Canada, Eritrea, Hong Kong, Netherlands, News and features, Philippines, Syria, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117182″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

The number of journalists killed while doing their work rose in 2020. It’s no wonder, then, that a team of internationally acclaimed lawyers are advising governments to introduce emergency visas for reporters who have to flee for their lives when work becomes too dangerous.

The High Level Panel of Legal Experts on Media Freedom, a group of lawyers led by Amal Clooney and former president of the UK Supreme Court Lord Neuberger, has called for these visas to be made available quickly. The panel advises a coalition of 47 countries on how to prevent the erosion of media freedom, and how to hold to account those who harm journalists.

At the launch of the panel’s report, Clooney said the current options open to journalists in danger were “almost without exception too lengthy to provide real protection”. She added: “I would describe the bottom line as too few countries offer ‘humanitarian’ visas that could apply to journalists in danger as a result of their work.”

The report that includes these recommendations was written by barrister Can Yeğinsu. It has been formally endorsed by the UN special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights special rapporteur for freedom of expression, and the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute.

As highlighted by the recent release of an International Federation of Journalists report showing 65 journalists and media workers were killed in 2020 – up 17 from 2019 – and 200 were jailed for their work, the issue is incredibly urgent.

Index has spoken to journalists who know what it is like to work in dangerous situations about why emergency visas are vital, and to the lawyer leading the charge to create them.

Syrian journalist Zaina Erhaim, who has worked for the BBC Arabic Service, has reported on her country’s civil war. She believes part of the problem for journalists forced to flee because of their work is that many immigration systems are not set up to be reactive to those kinds of situations, “because the procedures for visas and immigration is so strict, and so slow and bureaucratic”.

Erhaim, who grew up in Idlib in Syria’s north-west, went on to report from rebel-held areas during the civil war, and she also trained citizen journalists.

The journalist, who won an Index award in 2016, has been threatened with death and harassed online. She moved to Turkey for her own safety and has spoken about not feeling safe to report on Syria at times, even from overseas, because of the threats.

She believes that until emergency visas are available quickly to those in urgent need, things will not change. “Until someone is finally able to act, journalists will either be in hiding, scared, assassinated or already imprisoned,” she said.

“Many journalists don’t even need to emigrate when they’re being targeted or feel threatened. Some just need some peace for three or four months to put their mind together, and think what they’ve been through and decide whether they should come back or find another solution.”

Erhaim, who currently lives in the UK, said it was also important to think about journalists’ families.

Eritrean journalist Abraham Zere is living in exile in the USA after fleeing his country. He feels the visa proposal would offer journalists in challenging political situations some sense of hope. “It’s so very important for local journalists to [be able to] flee their country from repressive regimes.”

Eritrea is regularly labelled the worst country in the world for journalists, taking bottom position in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index 2021, below North Korea. The RSF report highlights that 11 journalists are currently imprisoned in Eritrea without access to lawyers.

Zere said: “Until I left the country, for the last three years I was always prepared to be arrested. As a result of that constant fear, I abandoned writing. But if I were able to secure such a visa, I would have some sense of security.”

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick is a journalist formerly based in Hong Kong who has recently moved to Taiwan. He has worked as an editor for the Hong Kong Free Press, as well as for the South China Morning Post, Time and The Wall Street Journal.

“I wasn’t facing any immediate threats of violence, harassment, that sort of thing, [but] the environment for the journalists in Hong Kong was becoming a lot darker and a lot more dire, and [it was] a lot more difficult to operate there,” he said.

He added that although his need to move wasn’t because of threats, it had illustrated how difficult a relocation like that could be. “I tried applying from Hong Kong. I couldn’t get a visa there. I then had to go halfway around the world to Canada to apply for a completely different visa there to get to Taiwan.”

He feels the panel’s recommendation is much needed. “Obviously, journalists around the world are facing politically motivated harassment or prosecution, or even violence or death. And [with] the framework as it is now, journalists don’t really fit very neatly in it.”

As far as the current situation for journalists in Hong Kong is concerned, he said: “It became a lot more dangerous reporting on protests in Hong Kong. It’s immediate physical threats and facing tear gas, police and street clashes every day. The introduction of the national security law last year has made reporting a lot more difficult. Virtually overnight, sources are reluctant to speak to you, even previously very vocal people, activists and lawyers.”

In the few months since the panel launched its report and recommendations, no country has announced it will lead the way by offering emergency visas, but there are some promising signs from the likes of Canada, Germany and the Netherlands. [The Dutch House of Representatives passed a vote on facilitating the issuance of emergency visas for journalists at the end of June.]

Report author Yeğinsu, who is part of the international legal team representing Rappler journalist Maria Ressa in the Philippines, is positive about the response, and believes that the new US president Joe Biden is giving global leadership on this issue. He said: “It is always the few that need to lead. It’ll be interesting to see who does that.”

However, he pointed out that journalists have become less safe in the months since the report’s publication, with governments introducing laws during the pandemic that are being used aggressively against journalists.

Yeğinsu said the “recommendations are geared to really respond to instances where there’s a safety issue… so where the journalist is just looking for safe refuge”. This could cover a few options, such as a temporary stay or respite before a journalist returns home.

The report puts into context how these emergency visas could be incorporated into immigration systems such as those in the USA, Canada, the EU and the UK, at low cost and without the need for massive changes.

One encouraging sign came when former Canadian attorney-general Irwin Cotler said that “the Canadian government welcomes this report and is acting upon it”, while the UK foreign minister Lord Ahmad said his government “will take this particular report very seriously”. If they do not, the number of journalists killed and jailed while doing their jobs is likely to rise.

[This week, 20 UK media organisations issued an open letter calling for emergency visas for reporters in Afghanistan who have been targeted by the Taliban. Ruchi Kumar recently wrote for Index about the threats against journalists in Afghanistan from the Taliban.] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Aug 2021 | Afghanistan, Belarus, Burma, China, Hong Kong, India, Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117177″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]There are moments as you’re watching the news when it feels as if the world is becoming an increasingly horrible place, that totalitarianism is winning, and that violence is the acceptable norm. It’s all too easy to feel impotent as the horror becomes normalised and we move on from one devastating news cycle to the next.

This week alone, in the midst of the joy and heartbreak of the Olympics, we have seen the attempted forced removal of the Belarusian sprinter Krystina Timanovskaya from Tokyo by Lukashenko’s regime. Behind the headlines, the impact on her family has been obvious – her husband has fled to Ukraine and will seek asylum with Krystina in Poland and there have been reports that even her grandparents have been visited by KGB agents in Belarus.

This served as a stark reminder, if we needed one, that Lukashenko is an authoritarian dictator who will stop at nothing to retain power. And this is happening today – in Europe. Our own former member of staff Andrei Aliaksandrau and his partner Irina have been detained for 206 days; Andrei faces up to 15 years in prison for treason; his alleged “crime” – to pay the fines of the protestors.

In Afghanistan, reports of Taliban incursions are now a regular feature of every news bulletin, with former translators who supported NATO troops being murdered as soon as they are found and media freedom in Taliban-controlled areas now non-existent. Six journalists have been killed this year, targeted by extremists, and reporters are being forced into hiding to survive. As the Voice of America reported last month: “The day the Taliban entered Balkh district, 20 km west of Mazar e Sharif, the capital of Balkh province last month, local radio station Nawbahar shuttered its doors and most of its journalists went into hiding. Within days the station started broadcasting again, but the programming was different. Rather than the regular line-up, Nawbahar was playing Islamist anthems and shows produced by the Taliban.”

Last Sunday, Myanmar’s military leader, Gen Min Aung Hlaing, declared himself Prime Minister and denounced Aung San Suu Kyi as she faces charges of sedition. Since the military coup in February over 930 have been killed by the regime including 75 children and there seems to be no end in sight as the military continue to clamp down on any democratic activity and journalists and activists are forced to flee.

At the beginning of this week Steve Vines, a veteran journalist who had plied his trade in Hong Kong since 1987, fled after warnings that pro-Beijing forces were coming for him. The following day celebrated artist Kacey Wong left Hong Kong for Taiwan after his name appeared in a state-owned newspaper – which Wong viewed as a ‘wanted list’ by the CCP. Over a year since the introduction of the National Security Law in Hong Kong the ramifications are still being felt as dissent is crushed and people arrested for previously democratic acts, including Anthony Wong, a musician who was arrested this week for singing at an election rally in 2018. Dissent must be punished even if it was three years ago.

And then there is Kashmir… On 5 August 2019, Narendra Modi’s government stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its special status for limited autonomy. Since that time residents inside Kashmir have lived under various levels of restrictions. Over 1,000 people are still believed to be in prison, detained since the initial lockdown began, including children. Reportedly 19 civilians have died so far this year caught in clashes between the Indian Army and militants. And on the ground journalists are struggling to report as access to communications fluctuates.

Violence and silence are the recurring themes.

Belarus, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Hong Kong, Kashmir. These are just five places I have chosen to highlight this week. Appallingly, I could have chosen any of more than a dozen.

It would be easy to try and avoid these acts of violence. To turn off the news, to move onto the next article in the paper and push these awful events to the back of our mind. But we have a responsibility to know. To speak up. To stand with the oppressed.

Behind every story, every statistic, there is a person, a family, a friend, who is scared, who is grieving and in so many cases are inspiring us daily as they stand firm against the regimes that seek to silence them. Index stands with them and as ever we shine a spotlight on their stories – so that we can all bear witness.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Jul 2021 | BannedByBeijing, China, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117061″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Threats to free speech and free expression come in many guises. In the year since I’ve joined the team at Index, I’ve used this blog to highlight issues as diverse as journalists being assassinated in Afghanistan to the threats of new British legislation on online harms.

One of recurring themes of my blogs has been the way in which authoritarian regimes and groups use every tool at their disposal to repress their populations. From Belarus to Myanmar, from Modi to Trump, we’ve seen global leaders act against their own populations to hold onto power and stop dissent.

For an organisation such as Index it would be easy to think that our job was solely to highlight the worst excesses of these despots, to shine a spotlight on their actions and to celebrate the work and activities of those inspirational people who stand up against this tyranny. And of course, that’s exactly what we were founded to do. But as the world moves on and technology and finance facilitate new ways of communicating to the world, Index also has a responsibility to investigate, analyse and expose the impact of some countries beyond their borders.

Over the course of the last year, Index’s attention has been drawn to the fact that there have been multiple high-profile examples of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) using its influence beyond its border in order to manipulate the world’s view of China and what it means to be Chinese:

Since the implementation of the National Security Law in Hong Kong in June 2020, universities in the UK and in the US have reportedly had to change the way they teach certain courses – grading papers by number not name, asking students to present anonymised work of others so nothing can be attributed to an individual student and limited debate in lectures. All in order to make sure that the students are protected, and their families aren’t targeted at home in China.

In September 2020 Disney released a new film – Mulan. This film not only represents Mulan as Han Chinese rather than Mongolian as she likely was in the legend, but it was also filmed, in part, in Xinjiang province, home of the persecuted Uighur community. Seemingly an effort to change the narrative on the ongoing Uighur genocide happening in Xinjiang.

In October 2020, a scheduled exhibition on Genghis Khan and the Mongol empire in Nantes, France was postponed – not because of Covid19 but because the CCP reportedly attempted to change the narrative of the exhibition, attempting to rewrite history.

It is clear that the CCP is using soft (sharp) power in a concerted effort to censor dissent and to create a narrative that is in keeping with Xi Jinping’s vision in an effort to secure international support for the CCP, which this year celebrates its 100th anniversary. We have no idea how strategic or vast this level of censorship is. What we do know is that it is happening across Europe and beyond.

It is in this vein that I’m delighted to be able to tell you about a new workstream for Index:

#BannedbyBeijing will seek to analyse and expose the extent to which China is trying to manipulate the conversation abroad.

Next week I’m delighted that we have an amazing panel to get the ball rolling and to establish how big an issue this is.

So join Mareike Ohlberg, Tom Tugendhat MP, Edward Lucas and our Chair Trevor Phillips, on Wednesday as they start this vital conversation. You can sign up here >> https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/banned-by-beijing-is-china-censoring-europe-tickets-162403107065[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Jun 2021 | Belarus, China, Hong Kong, News and features

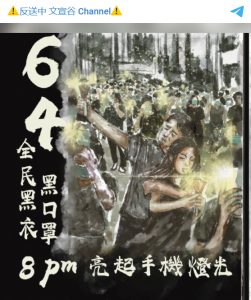

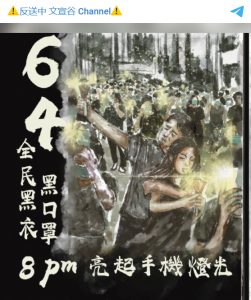

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

It shows crowds of young Hong Kongers, all dressed in black, at a protest, holding their smartphones aloft like virtual cigarette lighters from a Telegram channel called HKerschedule.

The image is an invitation for young activists to congregate and march to mark the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre on 4 June. Wearing black has been a form of protest for many years, which has led to suggestions that the authorities may arrest anyone doing so.

Calls to action like this have migrated from fly posters and other highly visible methods of communication online.

Secure messaging has become vital to organising protests against an oppressive state.

Many protest groups have used the encrypted service Telegram to schedule and plan demonstrations and marches. Countries across the world have attempted to ban it, with limited levels of success. Vladimir Putin’s Russia tried and failed, the regimes of China and Iran have come closest to eradicating its influence in their respective states.

Telegram, and other encrypted messaging services, are crucial for those intending to organise protests in countries where there is a severe crackdown on free speech. Myanmar, Belarus and Hong Kong have all seen people relying on the services.

It also means that news sites who have had their websites blocked, such as in the case of news website Tut.by in Belarus, or broadcaster Mizzima in Myanmar, have a safe and secure platform to broadcast from, should they so choose.

Belarusian freelance journalist Yauhen Merkis, who wrote for the most recent edition of the magazine, said such services were vital for both journalists and regular civilians.

“The importance of Telegram has grown in Belarus especially due to the blocking of the main news websites and problems accessing other social media platforms such as VK, OK and Facebook after August 2020,” he said.

“Telegram is easy to use, allows you to read the main news even in times of internet access restrictions, it’s a good platform to quickly share photos and videos and for regular users too: via Telegram-bots you could send a file to the editors of a particular Telegram channel in a second directly from a protest action, for example.”

The appeal, then, revolves around the safety of its usage, as well as access to well-sourced information from journalists.

In 2020, the Mobilise project set out to “analyse the micro-foundations of out-migration and mass protest”. In Belarus, it found that Telegram was the most trusted news source among the protesters taking part in the early stages of the demonstrations in the country that arose in August 2020, when President Alexander Lukashenko won a fifth term in office amidst an election result that was widely disputed.

But there are questions over its safety. Cooper Quintin, senior security researcher of the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit that aims to protect privacy online, said Telegram’s encryption “falls short”.

“End-to-end encryption is extremely important for everyone in the world, not just activists and journalists but regular people as well. Unfortunately, Telegram’s end-to-end encryption falls short in a couple of key areas. Firstly, end-to-end encryption isn’t enabled by default meaning that your conversations could be intercepted or recovered by a state-level actor if you don’t enable this, which most users are not aware of. Secondly, group conversations in Telegram are never encrypted [using end-to-end encryption], lacking even the option to do so, unlike other encrypted chat apps such as Signal, Wire, and Keybase.”

A Telegram spokesperson said: “Everything sent over Telegram is encrypted including messages sent in groups and posted to channels.”

This is true; however, messages sent using anything other than Secret Chats use so-called client-server/server-client encryption and are stored encrypted in Telegram’s cloud, allowing access to the messages if you lose your device, for example.

The platform says this means that messages can be securely backed up.

“We opted for a third approach by offering two distinct types of chats. Telegram disables default system backups and provides all users with an integrated security-focused backup solution in the form of Cloud Chats. Meanwhile, the separate entity of Secret Chats gives you full control over the data you do not want to be stored. This allows Telegram to be widely adopted in broad circles, not just by activists and dissidents, so that the simple fact of using Telegram does not mark users as targets for heightened surveillance in certain countries,” the company says in its FAQs.

The spokesperson said, “Telegram’s unique mix of end-to-end encryption and secure client-server encryption allows for the huge groups and channels that have made decentralized protests possible. Telegram’s end-to-end encrypted Secret Chats allow for an extra layer of security for those who are willing to accept the drawbacks of end-to-end encryption.”

If the app’s level of safety is up for debate, its impact and reach is less so.

Authorities are aware of the reach the app has and the level of influence its users can have. Roman Protasevich, the journalist currently detained in his home state after his flight from Greece to Lithuania was forcibly diverted to Minsk after entering Belarusian airspace, was working for Telegram channel Belamova. He previously co-founded and ran the Telegram channel Nexta Live, pictured.

Nexta’s Telegram page

Social media channels other than Telegram are easier to ban; Telegram access does not require a VPN, meaning even if governments choose to shut down internet providers, as the regimes in Myanmar and Belarus have done, access can be granted via mobile data. Mobile data is also targeted, but perhaps a problem easier to get around with alternative SIM cards from neighbouring countries.

People in Myanmar, for instance, have been known to use Thai SIM cards.

The site isn’t without controversy, however. Its very nature means it is a natural home for illicit activity such as revenge porn and use by extremists and terror groups. It is this that governments point to when trying to limit its reach.

China’s National Security Law attempts to censor information on the basis of criminalising any act of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with external forces, the threshold for which is extremely low. It has a particular impact on protesters in Hong Kong. Telegram was therefore an easy target.

In July 2020, Telegram refused to comply with Chinese authorities attempting to gain access to user data. As they told the Hong Kong Free Press at the time: “Telegram does not intend to process any data requests related to its Hong Kong users until an international consensus is reached in relation to the ongoing political changes in the city.”

Telegram continues to resist calls to share information (which other companies have done): it even took the step of removing mobile numbers from its service, for fear of its users being identified.

Anyone who values freedom of expression and the right to protest should resist calls for messaging platforms like Telegram to pull back on encryption or to install back doors for governments. When authoritarian regimes are cracking down on independent media more than ever, platforms like these are often the only way for protests to be heard

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.

As you scroll through your Telegram feed, one image jumps out.