5 Jul 2018 | News and features, Volume 47.02 Summer 2018, Volume 47.02 Summer 2018 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Vicky Baker, Meera Selva, Harriet Fitch Little and Benji Lanyado. Credit: Rosie Gilbey

“I would always err towards saying go rather than don’t go,” said Benji Lanyado, travel writer and founder of picture agency Picfair, speaking at a panel debate to launch the summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

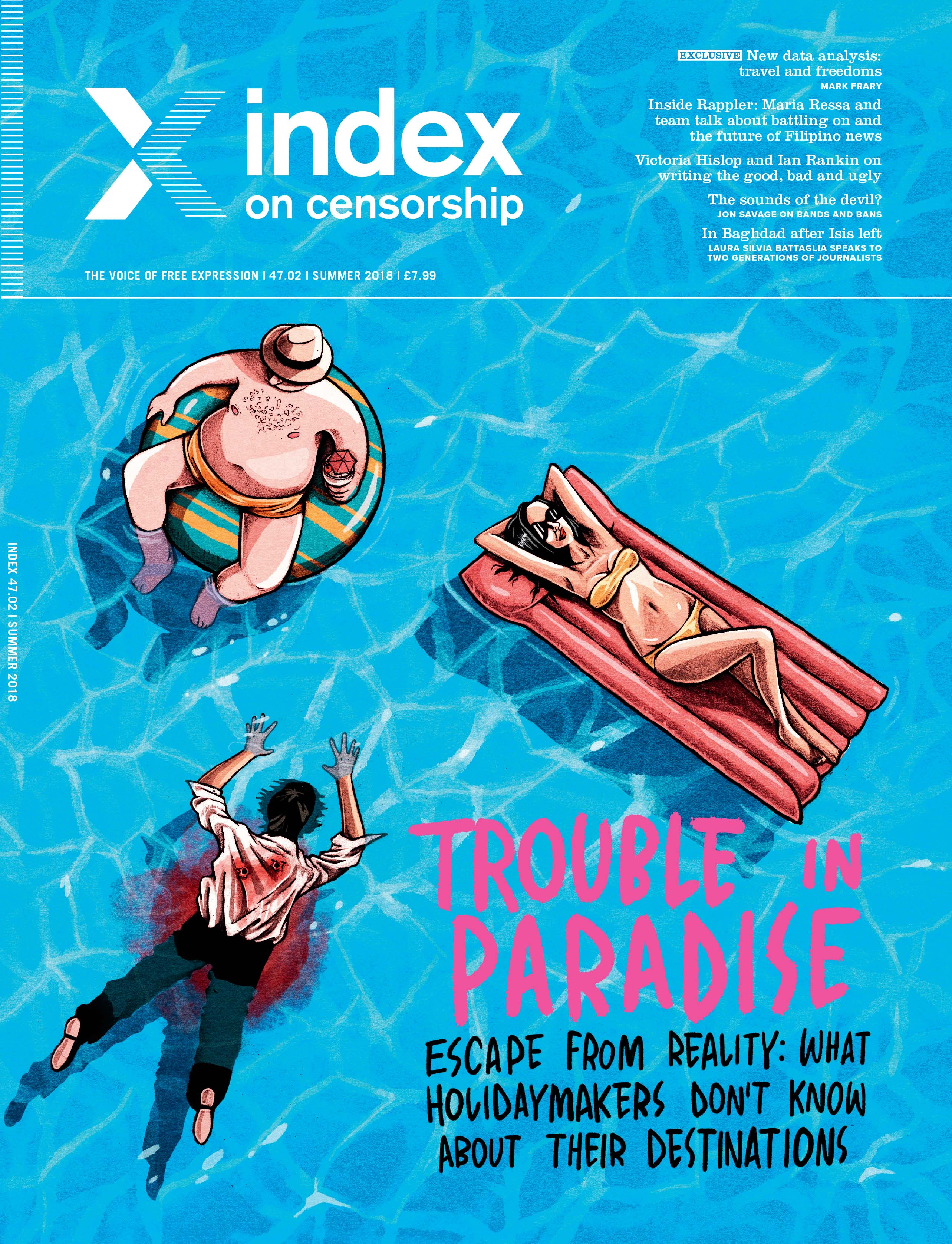

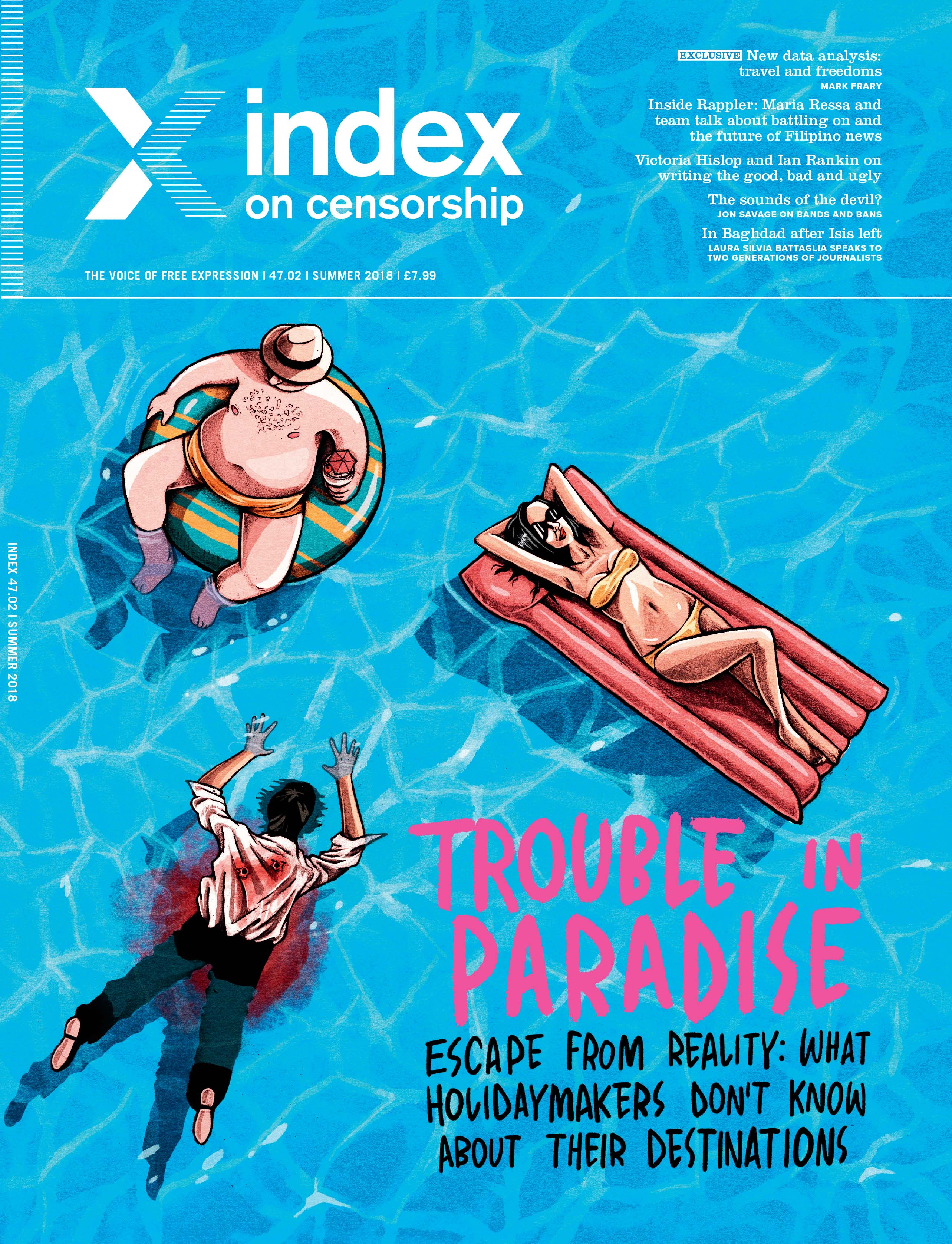

The latest issue of the magazine, Trouble in Paradise, looks at the free speech issues that are prominent in certain top travel destinations, and yet are often overlooked by tourists and the tourist industry. Countries covered included Mexico, Malta, the Philippines and the Maldives. For the launch, a panel of travel writers and editors shared their thoughts on the roles of writers to tell the full story, rather than the nice, PR holiday story, and discussed the free speech implications of travel.

Taking place at The Book Club in Shoreditch, London, Lanyado was joined by former foreign correspondent Meera Selva, and Harriet Fitch Little, a Financial Times writer. The discussion was chaired by Vicky Baker, a journalist at the BBC.

“The best travel writers do weave in the history and the politics of a place,” said Selva, while Fitch Little, talking about travel writing that might be paid for by travel companies or tourist boards as opposed to publications, said “there’s a way to write about a press trip that is fascinating and revealing.”

All panellists agreed on the value of speaking to locals in a destination, though they also acknowledged that doing so was not necessarily on the top of everyone’s holiday priority list, in particular families who might just want a nice break or might not have the budget for more adventurous travel – and that shouldn’t necessarily be condemned. “We all need escapism from time to time,” said Baker.

The panel also discussed whether travel journalists should write about problematic countries at all, raising questions about whether travelling to these places – and encouraging others to travel to them – benefits corrupt regimes.

“The best travel writers don’t just regurgitate the travel documents provided by the government,” Lanyado said.

“Sometimes you can get so obsessed by the pitfalls of a country and the leaders of a country that you forget about the people, and they can be totally different,” he added and asked whether boycotting a country was a form of censorship in its own right.

“If you don’t go, you don’t learn about the people,” said Baker.

Selva recalled a story of a travel journalist who went on a press trip to North Korea. While this journalist had first-hand experience of government propaganda, they also saw another side of the country when their bus driver did a detour into the countryside, heading off the beaten track. Had the travel journalist not gone, they would not have been able to report on this side.

The question of “ethical travel” was picked up by an audience member, Tina Urso from Malta, who spoke about Daphne Caruana Galizia, a Maltese journalist who was murdered on 16 October 2017 some 70 metres away from her home. Her death, which remains unsolved, exposed Malta’s dark side. There is now a memorial to Daphne opposite the central law courts in Valletta, the capital.

Urso said how this memorial is constantly dismantled, but that tourists, more so than locals, regularly rebuild it. She therefore saw the presence of tourists in Malta as playing a fundamental – and positive – role in highlighting these free speech abuses.

Finally, Fitch Little, who worked for local press in Lebanon and Cambodia, noted that there can sometimes be pressure coming from the other direction, namely pressure for writers to ham up the darker sides of destinations and that this too can conceal the real truth. She said how when writing about Cambodia, UK media often wanted a particular angle, usually one related to the Khmer Rouge.

Equally, when working for Time Out in Lebanon, her friends back home found it hard to believe that the country could have nice restaurants, for example, having seen the country in a more negative light. “Less sexy stories don’t get told,” she said.

For more information on the summer issue of the magazine, click here. Included in the issue is an article from a Maltese journalist, Caroline Muscat, on corruption in the country, a look at journalists living under protection due to their reporting of the drug wars in Baja California Sur and an interview with Federica Angeli, a journalist who lives under 24-hour police protection following her exposé of the mafia in the pretty Italian seaside resort of Ostia.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Trouble in Paradise”][vc_column_text]The summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes you on holiday, just a different kind of holiday. From Malta to the Maldives, we explore how freedom of expression is under attack in dream destinations around the world.

With: Martin Rowson, Jon Savage, Jonathan Tel [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”100843″ img_size=”medium”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Jun 2018 | Magazine, News and features, Press Releases

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

— Index special issue finds the dark side of summer holiday destinations not being reported on travel sites

— Editor calls on travel journalists to tell the whole story

— July 4 debate in London’s Book Club

With holidaymakers packing up for their summer trips, a new issue of Index on Censorship magazine reveals the uglier side of countries with tourist appeal and calls on travel writers to do more to give travellers the whole picture.

With holidaymakers packing up for their summer trips, a new issue of Index on Censorship magazine reveals the uglier side of countries with tourist appeal and calls on travel writers to do more to give travellers the whole picture.

Index editor Rachael Jolley said: “On travel websites for popular destinations like Mexico, Maldives and Malta there is little sign of the crackdown on freedoms we are seeing in these nations. From the horrific numbers of journalists being killed in Mexico, to the murder of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta, and anti-Muslim riots in Sri Lanka, with worshippers attacked on the way to mosques.

“I would like to see travel journalists do more to tell the whole story. With fewer travellers carrying print travel guides, which traditionally did give more background on political tensions and freedoms, digital versions need to step up to give travellers the full range of information, rather than just the glossy bits.”

“With many countries depending on travel spending as a vital part of their economy, the travel industry can also do more to press for change,” she added.

A discussion on the theme, will take place on 4 July at the Book Club in Shoreditch, chaired by BBC World journalist Vicky Baker. Panellists include former foreign correspondent Meera Selva, founder of the travel picture agency Picfair, Benji Lanyado, and Harriet Fitch Little, who writes for the Financial Times travel section, and formerly worked as a journalist in Lebanon.

Tourism is the main pillar of Mexico’s Baja California Sur’s economy, which is now the setting of some of the fiercest drug battles in the country. Conditions for journalists and human rights activists have deteriorated dramatically, according to the Index report Trouble in Paradise.

The security profile of Baja California Sur has changed enormously, but because it’s a tourist spot the government wants to hide that, Mexico correspondent Stephen Woodman writes in the Index report.

Journalist Federica Angeli, whose exposure of mafia in the pretty seaside town of Ostia, near Rome, has resulted in her having to live under 24-hour police protection. “Ostia is a paradise inhabited by demons,” Angeli told Index.

In Malta, where the recent murder of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia remains largely unsolved, Maltese journalist Caroline Muscat writes: “Those who mention her name, those who refuse to bow to a society bent by corruption, are insulted and threatened. Journalists and activists keep being reminded of the untold damage they are doing to the country’s reputation.”

Honeymoon destination the Maldives is also covered. The “disappearance” of a journalist, the killing of a blogger, death threats, imprisonment and hefty fines are placing an enormous pressure on those who seek to inform the public about what is going on, writes Zaheena Rasheed.

Just how much do these darker sides affect tourism? New data analysed exclusively for Index looks at the power of tourism spend, and just how valuable tourism is to economies such as Mexico and the Maldives.

Also in the magazine: how journalists’ conditions are deteriorating in Iraq, despite the retreat of Isis, Jon Savage on bands and bans, and Filipino news boss Maria Ressa on keeping going despite government pressure for her news operation to give up, plus a short story on the future of facial recognition by award-winning writer Jonathan Tel.

Editors’ notes:

For media tickets to the debate, email: [email protected]

Index on Censorship magazine was first published in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Since then, some of the greatest names in literature and academia have written for the magazine, including Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Amartya Sen, Samuel Beckett, as well as Arthur Miller and Harold Pinter. The magazine continues to attract great writers, passionate arguments, and expose chilling stories of censorship and violence. It is the only global free expression magazine.

Each quarterly magazine is filled with reports, analysis, photography and creative writing from around the world. Index on Censorship magazine is published four times a year by Sage, and is available in print, online and mobile/tablets (iPhone/iPad, Android, Kindle Fire).

Winner of the British Society of Magazine Editors 2016 Editor of the Year in the special interest category.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Trouble in paradise” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F06%2Ftrouble-in-paradise%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how holidaymakers’ images of palm-fringed beaches and crystal clear waters contrast with the reality of freedoms under threat

With: Ian Rankin, Victoria Hislop, Maria Ressa [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”100776″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/06/trouble-in-paradise/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Jun 2018 | News and features, Volume 47.02 Summer 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Crime writers have less to lose than travel writers in describing the underside of holiday spots, argues Rachael Jolley in the summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_single_image image=”101057″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

When you read a novel, it takes you on a journey to a different time or place. Being an avid reader of crime fiction, my early journeys to Chicago were in the company of Sara Paretsky. I walked the streets with her VI Warshawski. We shot down North Michigan Avenue and headed out to Wrigley Field for the fifth inning. Chicago opened up to me in those books – not always gloriously.

Donna Leon showed me around the small islands of the Venetian Lagoon and Ian Rankin has taken me on numerous tours of the dark closes of Edinburgh, as well as its swankier New Town.

Crime writers have less to lose than many other authors in describing the underside of the cities. After all, their readers don’t expect a fairytale, and their escapism is a different kind from the happy-ever-afters of the perfect beach-read.

Perhaps we get more accurate portrayals of cities or countries by crime writers than in guidebooks or from travel apps.

Take Mexico and the Maldives, for instance. These are sexy holiday destinations, popular with everyone from honeymooners to scuba divers. But when thousands of holidaymakers are packing their sunscreen and swimsuits, do they know of the catastrophic numbers of journalists killed in Mexico in the past few years? Or how journalists in the Maldives are fleeing in fear of their lives?

Ad-hoc, non-scientific research, through the medium of asking friends and family, suggests not. And when that information is received, it is with some shock.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The results are stark. Many top tourism destinations do terribly on freedom of expression.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The other side: Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was murdered on 16 October 2017

Mexico is ranked 147th out of 180 in the 2018 Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index, down from 75th in 2002. During this period, tourist numbers have continued to go up. Meanwhile, 4.6% of the government’s annual spend continues to go on tourism, significantly more than is spent in Brazil and New Zealand, for instance.

Travel and tourism delivers 6.9% of Mexico’s GDP, compared with 3.3% of Brazil’s and 5.1% of New Zealand’s. No wonder, then, that Mexico’s government is prepared to invest in tourism, and to keep that tap firmly switched on.

Informed tourists could be a powerful pressure point on governments that have been practising repression of those voices raised in criticism, or that don’t bother to pursue the criminals who threaten or kill those voicing dissent.

At this year’s Hay Festival, I was on a panel with Paul Caruana Galizia, son of the murdered journalist Daphne, as well as Malta journalist Caroline Muscat of The Shift News, and BBC Europe editor Katya Adler. Paul talked about his mother’s work, the pressures she was under and how she pursued her investigations. We discussed the wider situation in Malta, where 34 libel cases against Daphne have, since her death, rolled over to the rest of the family. During the question and answer session, some members of the audience said they had no idea about what was going on in Malta, even though they went there on holiday, and asked what they could do to help.

Paul suggested that anyone holidaying on the Mediterranean island might mention being aware of the case to local people they met. The island was dependent on tourism, and if the Maltese felt this could be affected there would be more pressure on the government to alter its attitude, and legislation, on media freedom.

He also believed the Maltese government was much more worried about international attitudes than local ones.

In places where freedom of expression is under pressure – and Malta, the Maldives and Mexico are just a few of them – tourism is often a valuable asset. So visitors who are aware of the wider situation could be advocates for change.

According to analysis of travel, tourism, financial and freedom-of-expression data carried out for Index on Censorship magazine by Mark Frary, there are indications that some tourists want to know more than whether or not a destination has a good beach before they head off on holiday.

Data on travel patterns suggest that travellers also “reward” destinations that change legislation or the environment, his analysis suggests, with Argentina picking up significant tourist numbers after it became the first South American country to make gay marriage legal.

In this issue, we have asked reporters around the world to dig into the details of popular holiday destinations to look at their records on freedoms, such as the right to protest, the right to debate and freedom of the media. The results are stark. Many top tourism destinations do terribly on freedom of expression.

In post civil war Sri Lanka, there was a period of hope after the election of Prime Minister Maithripala Sirisena in 2015. Many hoped that this beautiful island could have a future that was less violent, more equal and more open. Those hopes are now looking tarnished. As Meera Selva reports for the magazine, the country’s tourist numbers grew spectacularly in 2017. But while tourists flocked in, the great improvement was not going as well as Sri Lankans had wished.

The prime minister has reactivated the Press Council – a body with the power to imprison journalists – and civil rights activists report threats against them. In this potential Eden, the garden is not as green and pleasant as predicted.

Pretty beach paradise Baja California Sur is a popular holiday destination, particularly for Americans. But not many will know that it also has the second-highest murder rate in Mexico, behind the western state of Colima, according to government data. The dangers of being an investigative journalist there are particularly high, with some living under 24-hour protection, as Stephen Woodman reports in the magazine. Again, this is a place where many (probably most) tourists are unaware of the fuller picture of the place where they are happily enjoying the sunshine.

As someone with a heritage collection of guidebooks from publishers including Lonely Planet, Rough Guides and Footprint, it is easy for me to flick through the pages and see that those guides have made a fair effort to inform readers on questions of human rights, politics and safety in the past.

But guidebooks are carried by far fewer travellers these days. According to the Financial Times, from 2005 to 2014, 9% fewer travellers left the UK but guidebook sales fell by 45%.

With most people looking to the web for all their holiday information, are they finding themselves as well-informed as they would have been with a well-thumbed book under their arm?

An April 2018 travel section article about Malta’s capital Valletta on The Guardian’s website doesn’t mention the politics or human rights record of the island. Nor, as far as I could find, did the Lonely Planet website section on Malta. While, of course, it would be possible to find news about those issues on different parts of The Guardian site, or elsewhere on the web, it’s certainly not connecting the dots for travellers.

With the printed travel sections of newspapers under pressure from advertisers – and far smaller than they were a decade ago – there is little space to create in-depth reports, and travel articles that include gritty details as well as the delights seem few and far between.

At the upcoming Index magazine launch and summer party on 4 July, our panel of experts will discuss what responsibility authors might have to tell their readers about the good, the bad and the ugly sides of any destination. It should be an interesting evening, chaired by BBC World reporter Vicky Baker, who also writes for Guardian Travel. If you would like to join us, email [email protected] to grab a free ticket.

And since we are just back from the Hay Festival, we can also recommend our special Hay Festival podcast, where deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld chats to three authors about taboos. Catch it on Soundcloud.com/indexmagazine.

Finally, don’t miss our regular quarterly magazine podcast, also on Soundcloud, including an interview with the founder of the Rough Guides, Mark Ellingham. Come by and visit us.

The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Trouble in Paradise, Escape from Reality: what holidaymakers don’t know about their destinations is out now. Buy a subscription. Buy a print copy from bookshops including BFI, Serpentine and MagCulture (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), and Red Lion Books (Colchester), or via Amazon. Digital versions available via exacteditions.com or iTunes.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Trouble in paradise” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F06%2Ftrouble-in-paradise%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how holidaymakers’ images of palm-fringed beaches and crystal clear waters contrast with the reality of freedoms under threat

With: Ian Rankin, Victoria Hislop, Maria Ressa [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”100776″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/06/trouble-in-paradise/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

With holidaymakers packing up for their summer trips, a new issue of

With holidaymakers packing up for their summer trips, a new issue of