3 Jan 2019 | Artistic Freedom, Index Arts, Magazine, News and features, Student Reading Lists, Volume 47.04 Winter 2018 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

An anti-war mural created by Yemeni street artist Murad Subay, 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award winner.

Art has been used as a form of protest during times of crisis throughout history. It is a popular and, at times, effective platform to express opinions about societal or governmental problems, particularly when other forms of protest are not available. Protest art includes performances, site-specific installations, graffiti and street art.

Here Index highlights key articles about art and protest from around the world, from the past five decades.

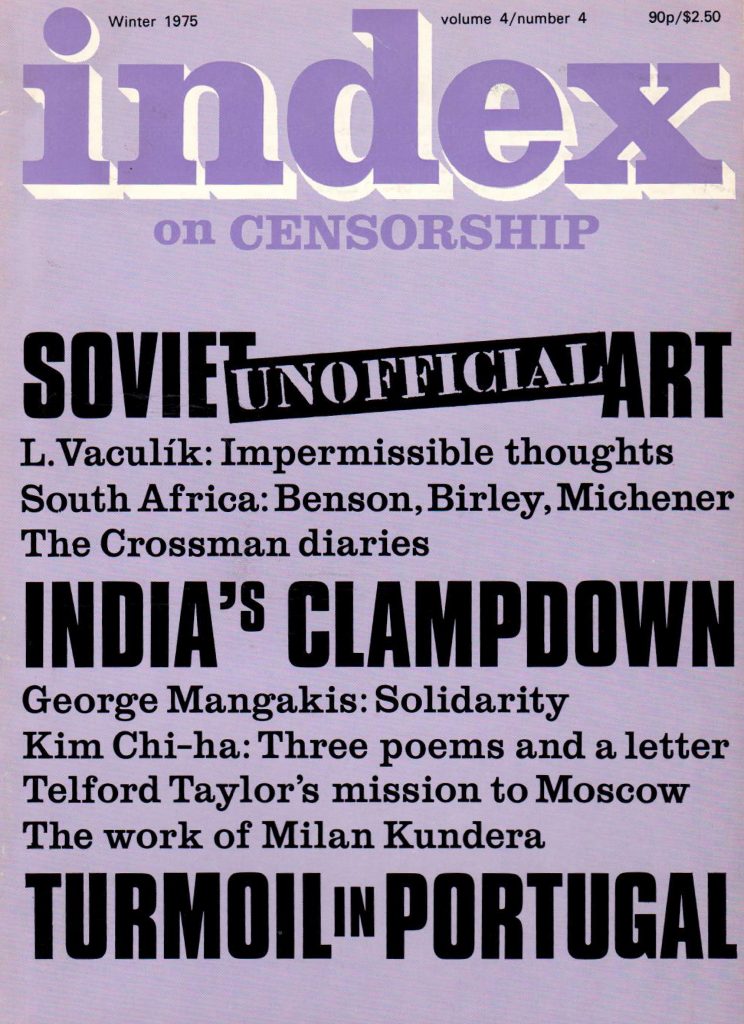

Soviet “unofficial” art

December 1975, vol. 4 issue: 4

Alexander Glezer writes about his participation in organising the unofficial art exhibit in Moscow. When the first exhibition opened, it was bulldozed by undercover police officers and agents from the KGB (Committee for State Security). In the second exhibition, the authorities were forced by the public to grant permission and ten to fifteen thousand people came to see the paintings and sculptures of 50 nonconformist artists’. Glezer, 41-years-old, was questioned by the KGB, arrested and sentenced 10 days for “hooliganism”. He was allowed to leave the Soviet Union in 1975 February.

Read the full article

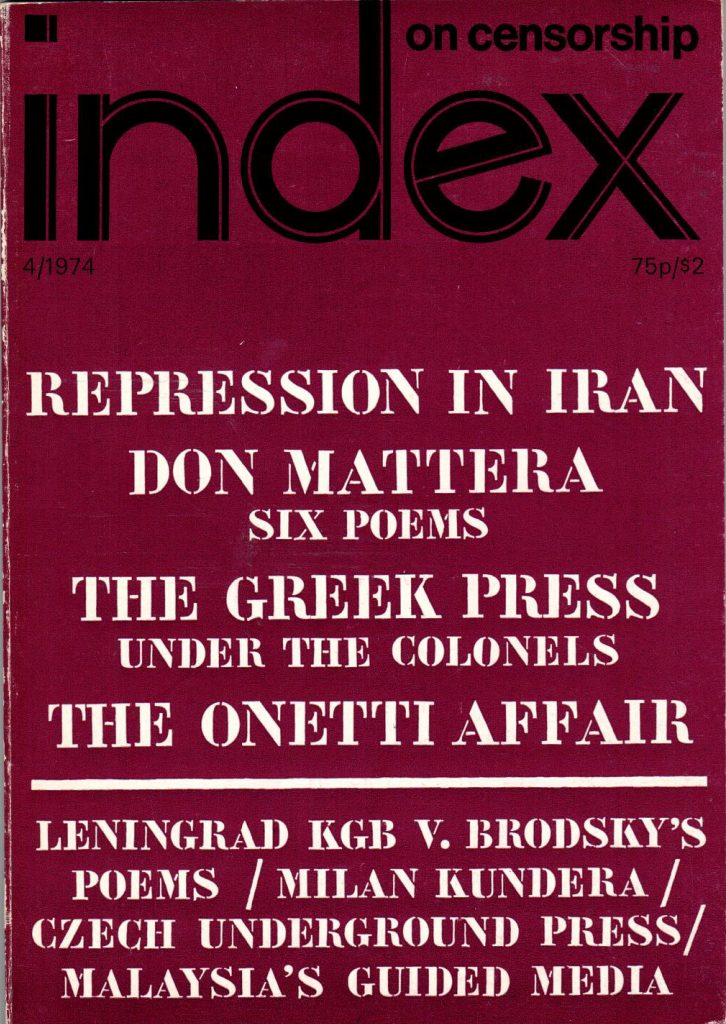

Portugal: Art triumphant

December 1974, vol. 3 issue: 4

The Sao Mamed Gallery opened with 186 artworks by 87 artists who had never shown their work in public before due to the regime’s dictating of Portuguese life. The gallery was built to celebrate the result of the military coup abolishing censorship of expression.

Published in the New York Times.

Read the full article

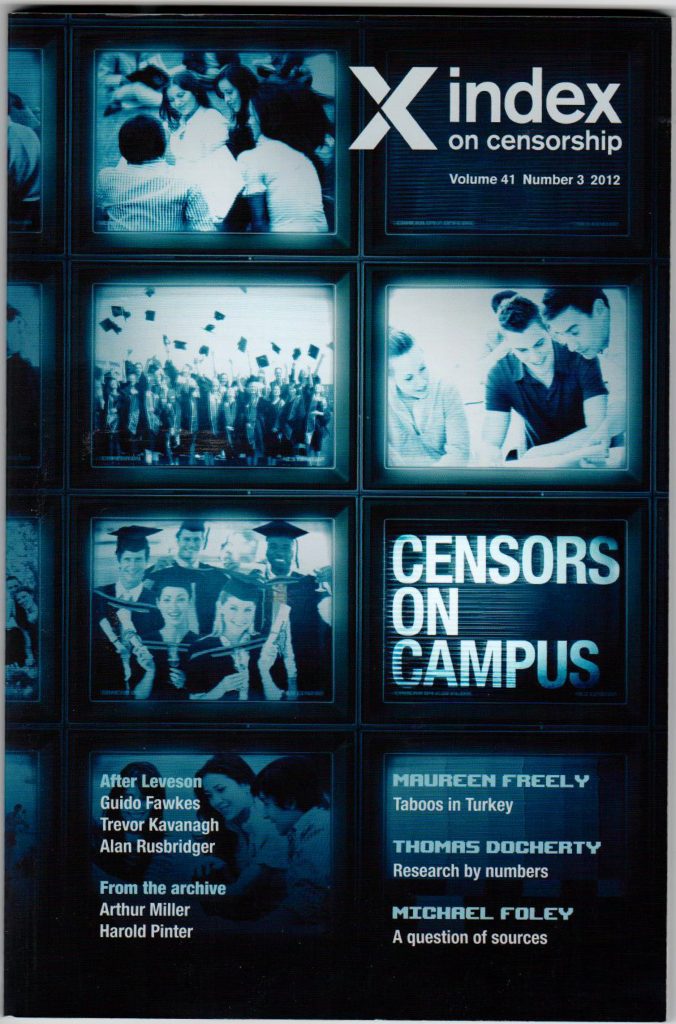

Art of Resistance

September 2012, vol. 41 issue: 3

Malu Halasa, co-curator of the exhibition Culture in Defiance: Continuing Traditions of Satire, Art and the Struggle for Freedom in Syria, writes about how the violence in Syria affected country’s art of resistance production and then created ideas of spreading this work further West which was the reason for the exhibition’s creation.

Read the full article

Dark Arts: Three Uzbek artists speak out on state constraints

December 2014, vol. 43 issue: 4

Author Nargis Tashpulatova interviews writer three Uzbek artists – Sid Yanishev, photographer Umida Akhmedova and conceptual artist Vyacheslav Akhunov who continue to create artwork throughout governmental threats and censorship and the regression of art in Uzbek society.

Read the full article

Art or Vandalism

October 2011, vol. 40 issue: 3

Yasmine El Rashidi writes on the outbreak of graffiti in the streets in Cairo during the 18 days of the Egyptian revolution.

Read the full article

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1546513460633-7f241be5-ccf1-1″ taxonomies=”8890″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Events, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”104276″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Join Julia Farrington, associate arts producer at Index on Censorship, psychoanalyst and professor Adam Phillips, and artist Celia Hempton as they discuss the challenges in creating erotic art in today’s contemporary art world with journalist and broadcaster Kirsty Wark.

Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele were two artists that frequently scandalised their audiences in the early 20th century. But what if they were making the same works now – would they be censored? What defines erotic art? Who decides when erotica crosses the line into pornography?

In an age of successful digital media platforms and the prolific production of transgressive artworks, new methods of censorship have become a controversial and impeding issue for contemporary artists. Our panel investigate how censorship has changed in the digital age and to what extent it stifles an artist’s creativity.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”104271″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Julia Farrington

Farrington is associate arts producer at Index on Censorship. She runs Index’s UK programme monitoring contemporary forms of censorship and self-censorship in the arts and reinforcing institutional support for artistic freedom of expression. She co-edited Art and the Law, a series of bespoke information packs for the arts sector, looking at the rights and legal framework around what is sayable in the arts in the UK. She has also worked with the police, examining their role in the removal or cancellation of controversial artworks in recent years, and is currently heading up Risks, Rights, Reputation – challenging a risk averse culture an Arts Council England-funded training programme for CEOs and trustees of arts organisations.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”104273″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Celia Hempton

Hempton lives and works in London. Her work is included in public and private collections including Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín, Colombia, The British Council, London, UK, DRAF, London, UK, Fiorucci Art Trust, London, UK. Current and forthcoming exhibitions include Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today, Michigan Museum of Art, USA, Taking Up Space, Government Art Collection, London (2018), Tainted Love, Villa Arson, Nice, France, Personal Private Public, Hauser & Wirth, New York (2019).[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”104270″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Adam Phillips

Phillips, formerly Principle Child Psychotherapist at Charing Cross Hospital, London, is a practising psychoanalyst and a visiting professor in the English department at the University of York. He is the author of numerous works of psychoanalysis and literary criticism, including most recently Unforbidden Pleasures, and Missing Out. He is General Editor of the Penguin Modern Classics Freud translations, and a Fellow of The Royal Society of Literature.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”104272″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]Kirsty Wark

Wark is one of Britain’s most experienced television journalists. She has presented a wide range of programmes including the BBC’s flagship nightly current affairs show Newsnight. She also hosted the weekly Arts and Cultural review and comment show, The Review Show (formerly Newsnight Review) for over a decade. She has conducted long form interviews with everyone from Margaret Thatcher to Madonna, Harold Pinter, Elton John, the musician Pete Doherty, Damian Hirst to George Clooney and the likes of Toni Morrison, Donna Tartt and Philip Roth. Her debut novel, The Legacy of Elizabeth Pringle, was published in March 2014 by Two Roads – an imprint of Hodder & Stoughton. She is currently writing her second novel.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Cuba, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The artist Tania Bruguera who was detained last week with fellow artists in Cuba for protesting against Decree 349, an artistic censorship law, has written an open letter explaining why she will not attend Kochi biennial at a time that is crucial for freedom of expression in Cuba and beyond.

Bruguera who was due to attend Kochi states in the letter:

“At this moment I do not feel comfortable traveling to participate in an international art event when the future of the arts and artists in Cuba is at risk… As an artist I feel my duty today is not to exhibit my work at an international exhibition and further my personal artistic career but to expose the vulnerability of Cuban artists today.”

Bruguera feels it is important to highlight the situation in Cuba and also to see it as part of a global phenomenon of repression of artists and freedom of expression. Recent cases such as Shahidul Alam, the photographer imprisoned by the government of Bangladesh (who Bruguera campaigned for by hosting two protest shows at Tate Modern in October), the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi killed in the Saudi embassy in Turkey, and photographer Lu Guang who has gone missing in China, demonstrate that governments feel emboldened to openly attack high profile figures, moving beyond internal state repression which used to happen behind closed doors.

On Wednesday 5 December supporters of Bruguera held a protest exhibition at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, where participants spoke on a microphone about Decree 349 and the abuse of artists around the world. Alistair Hudson, director of the Whitworth and Manchester Art Gallery spoke at the event via live phone in. Tate director Maria Balshaw, also spoke out on the BBC news broadcast of the Turner Prize whilst Tate Modern director Frances Morris made a statement on Tate twitter. A speech by HRH Prince Constantijn on the occasion of the 2018 Prince Claus Awards at the Royal Palace, Amsterdam on 6 December 2018 also spoke about the situation with reference to Tania Bruguera, Shahidul Alam and Lu Guang. Many other cultural institutions around the world have also made public statements, whilst others are showing signs that they will follow.

The hope is that art institutions and events around the world, such as Kochi biennial, follow suit and show open solidarity to defend the artists’ space.

The full wording of Bruguera’s letter is as follows:

OPEN LETTER BY TANIA BRUGUERA TO THE DIRECTOR OF KOCHI BIENNALE ON DECREE 349

At this moment I do not feel comfortable traveling to participate in an international art event when the future of the arts and artists in Cuba is at risk. The Cuban government with Decree 349 is legalizing censorship, saying that art must be created to suit their ethic and cultural values (which are not actually defined). The government is creating a `cultural police´ in the figure of the inspectors, turning what was until now, subjective and debatable into crime.

Cuban artists have united for the first time in many decades to be heard, each with their own points of view. They had meetings with bureaucrats from the Ministry of Culture who promised them that they would meet again to give them answers. Instead, the Minister and other bureaucrats appeared on TV and made comments such as “[those who oppose Decree 349] want the dissolution of the institution” and “the alternative they are proposing is the commercialisation of art.”

Nothing could be further from the truth. If this were true, the artists would not have written to the institutions and sought dialogue with them.

But, a public opinion campaign by the government against the artists, with the intention to divide between “good ones” and “bad ones”, has started. This is even more concerning when under this decree the law restricts but provides no guarantee of whether an artist will or will not be criminalized or not at any time.. Moreover, the decree states that all `artistic services´ must be authorized by the Ministry of Culture and its correspondent institutions, making independent art impossible.

The last time a decree of this sort was enacted was the no. 226 from November 29 of 1997, which is evidence of the long life that such a decree could have and its long term impact on our culture.

As an artist I feel my duty today is not to exhibit my work at an international exhibition and further my personal artistic career but to be with my fellow Cuban artists and to expose the vulnerability of Cuban artists today.

We are all waiting for the regulations and norms the Ministry of Culture will put forward to implement Decree 349 in the hope that they include the suggestions and demands so many artists shared with them. I would like to add that the instructor from the Ministry of Interior who is in charge of my case menaced me yesterday, saying that if I didn’t leave Cuba and if I did `something´, I would not be able to leave in the future.

Injustice exists because previous injustices were not challenged.

Ironically, I’m sending you this text on December 10th the International Day of Human Rights.

Un abrazo,

Tania Bruguera[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1544431942749-6dbcba3e-bd36-2″ taxonomies=”15469, 7874″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Dec 2018 | Artistic Freedom, Awards, Cuba, Fellowship, Fellowship 2019, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Update: All arrested artists have now been released, although they remain under police surveillance. Cuba’s vice minister of culture Fernando Rojas has declared to the Associated Press that changes will be made to Decree 349 but has not opened dialogue with the artists involved in the campaign against the decree.

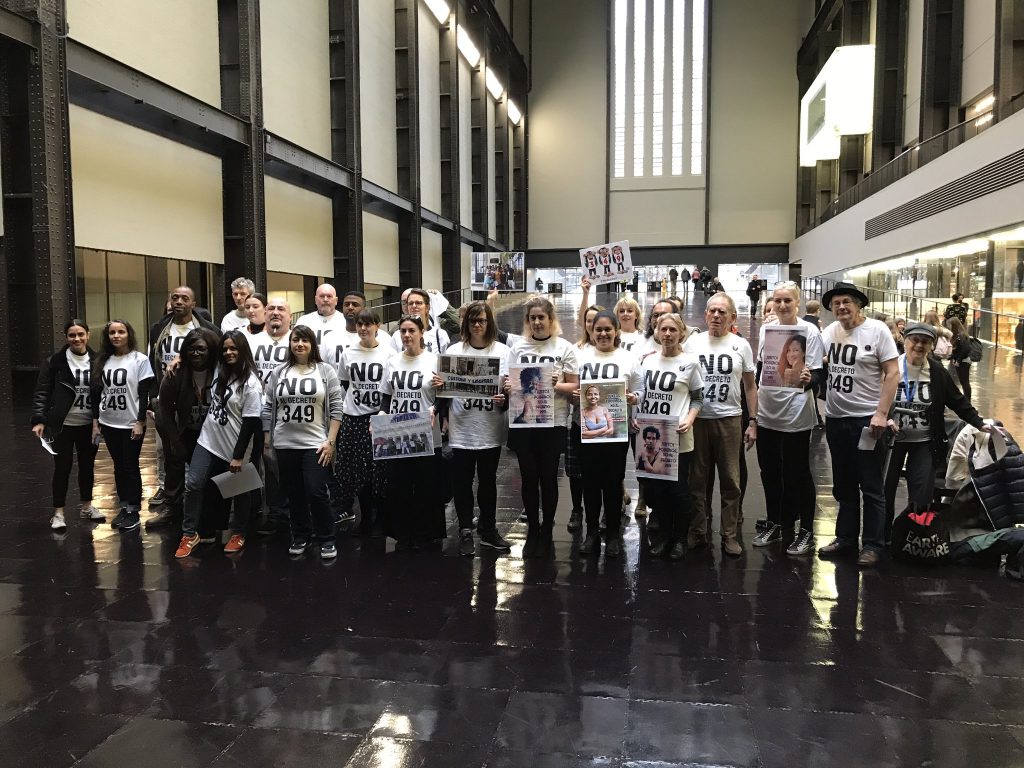

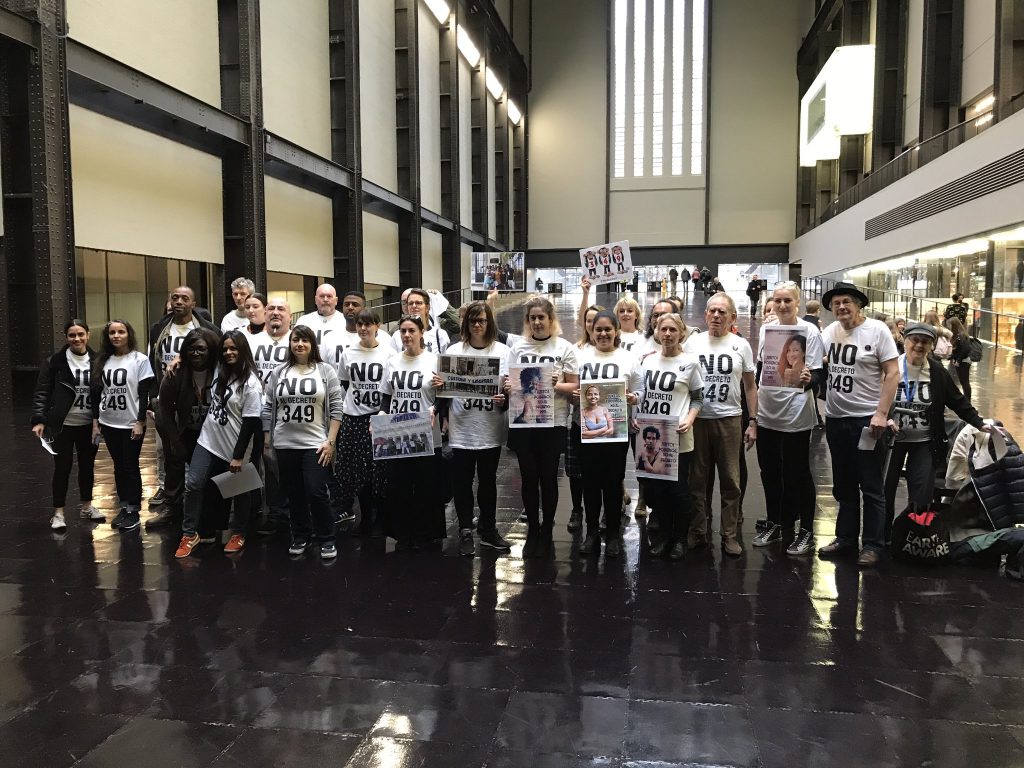

Index on Censorship joined others at the Tate Modern on 5 December in a show of solidarity with those artists arrested in Cuba for peacefully protesting Decree 349, a law that will severely limit artistic freedom in the country. Decree 349 will see all artists — including collectives, musicians and performers — prohibited from operating in public places without prior approval from the Ministry of Culture.

In all, 13 artists were arrested over 48 hours. Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Museum of Dissidence, were arrested in Havana on 3 December. They are being held at Vivac prison on the outskirts of Havana. The Cuban performance artist Tania Bruguera, who was in residency at the Tate Modern in October 2018, was arrested separately, released and re-arrested. Of all those arrested, only Otero Alcantara, Nuñez Leyva and Bruguera remain in custody.

Index on Censorship’s Perla Hinojosa speaking at the Tate Modern.

Speaking at the Tate Modern, Index on Censorship’s fellowships and advocacy officer Perla Hinojosa, who has had the pleasure of working with Otero Alcantara and Nuñez Leyva, said: “We call on the Cuban government to let them know that we are watching them, we’re holding them accountable, and they must release artists who are in prison at this time and that they must drop Decree 349. Freedom of expression should not be criminalised. Art should not be criminalised. In the words of Luis Manuel, who emailed me on Sunday just before he went to prison: ‘349 is the image of censorship and repression of Cuban art and culture, and an example of the exercise of state control over its citizens’.”

Other speakers included Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions at Tate, Jota Castro, a Dublin-based Franco-Peruvian artist, Sofia Karim, a Lonon-based architect and niece of the jailed Bangladeshi photojournalist Shahidul Alam, Alistair Hudson, director of Manchester Art Gallery and The Whitworth, and Colette Bailey, Artistic director and chief executive of Metal, the Southend-on-Sea-based arts charity.

Some read from a joint statement: “We are here in London, able to speak freely without fear. We must not take that for granted.”

It continued: “Following the recent detention of Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam along with the recent murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, there us a global acceleration of censorship and repression of artists, journalists and academics. During these intrinsically linked turbulent times, we must join together to defend our right to debate, communicate and support one another.”

Castro read in Spanish from an open declaration for all artists campaigning against the Decree 349. It stated: “Art as a utilitarian artefact not only contravenes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Cuba is an active member of the United Nations Organisation), but also the basic principles of the United Nations for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO).”

It continued: “Freedom of creation, a basic human expression, is becoming a “problematic” issue for many governments in the world. A degradation of fundamental rights is evident not only in the unfair detention of internationally recognised creatives, but mainly in attacking the fundamental rights of every single creator. Their strategy, based on the construction of a legal framework, constrains basic fundamental human rights that are inalienable such as freedom of speech. This problem occurs today on a global scale and should concern us all.”

Cuban artists Luis Manuel Otero Alcantara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, members of the Index-award winning Museum of Dissidence

Mohamed Sameh, from the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Egypt Commission on Rights and Freedoms, offered these words of solidarity: “We are shocked to know of Yanelys and Luis Manuels’s detention. Is this the best Cuba can do to these wonderful artists? What happened to Cuba that once stood together with Nelson Mandela? We call on and ask the Cuban authorities to release Yanelys and Luis Manuel immediately. The Cuban authorities shall be held responsible of any harm that may happen to them during this shameful detention.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1544112913087-f4e25fac-3439-10″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]