16 Feb 2015 | Campaigns, Denmark, News and features, Statements, United Kingdom

Free speech is under attack. We need to defend it.

On Friday night, I moderated a public debate to discuss hate speech in the wake of Charlie Hebdo. The panellists were free speech experts and academics. The London audience was the largely familiar bunch of interested activists and writers, plus a handful of individuals newly interested in questions of free speech following the Paris attacks.

I left the debate feeling energised and upbeat: if one good thing had come out of the horrors of Paris, it was a renewed interest in debating the value of free speech, I thought. People might not always agree with our position – that incitement to violence should be the only legal limits placed on free speech – but at least there were more people interested in hearing the debate. That willingness to listen, to hear the views of others, as well as the ability to express them is – after all – what lies at the heart of free expression.

Less than 24 hours later, came news that at a similar event – a seminar discussing art and blasphemy in Copenhagen – a gunman had shot at the audience, killing a 55-year old filmmaker. This was an event just like ours. One of the speakers was controversial in a way none of ours had been – a Swedish cartoonist who had lampooned the Prophet Mohammed – but otherwise there was little difference: a small-scale event, with a small audience seeking to understand the benefits of free speech, and its challenges, one of many such events that have been held since the Charlie Hebdo attacks.

That incident generated intense debate about what constitutes offence, about whom we should be allowed to insult and how, even about the quality of satire. And it spurred a host of declarations that began “I support free speech” and which then almost always came with a qualification: “I support free speech, but I don’t think it’s right to offend anyone…” or “I support free speech, but if you insult my mother then it’s OK for me to punch you…” or “I support satire, but only when it’s good art…”.

If you were one of those people, try thinking about this: I find it offensive that in many parts of the world people are regularly beaten, jailed and murdered for daring to follow a different belief system or for daring to suggest they want a democratic government. I find it offensive that the majority of decisions in the UK parliament, in the judiciary, in the arts, are made by a small group of people who can shut out the views of large swathes of the population. I find the portrayal of women by much of the British media offensive. These things make me angry. But the fact that I find them offensive or anger-inducing cannot, and should never, be used as an excuse for shutting down their speech. Because that is exactly how millions of people are silenced the world over, how repressive regimes thrive through law, or through violence, or both. And what protects people’s rights to say things I find objectionable is precisely what protects my right to object.

Related:

Index on Censorship statement on blasphemy debate attack in Copenhagen

This article was originally posted at Comment Is Free on February 16 2015

16 Feb 2015 | Draw the Line, mobile

Growth can only happen when old obsolete ideas are replaced with newer, relevant ones. If we don’t challenge the established system of thought, we can’t move forward. If ideas that don’t work anymore aren’t rejected, new ones won’t find space. Without new and better ideas there is no movement in any field. Freedom of speech and expression is fundamental to that forward movement and as Salman Rushdie said, “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist”

We opened up the debate with Charlie Hebdo on our minds. The Hebdo massacre changed the world. Now there is an actual discourse on free expression across the globe. The world is coming together and expressing themselves collectively. Our twitter feed is proof of that. While a lot of people believe that the right to offend comes with the right to free expression, there are people who say that anything that leads to violence is wrong, and there is a fine line there which needs to be observed.

This is where we draw the line: somewhere in the ever-changing grey area between absolutism and stagnancy.

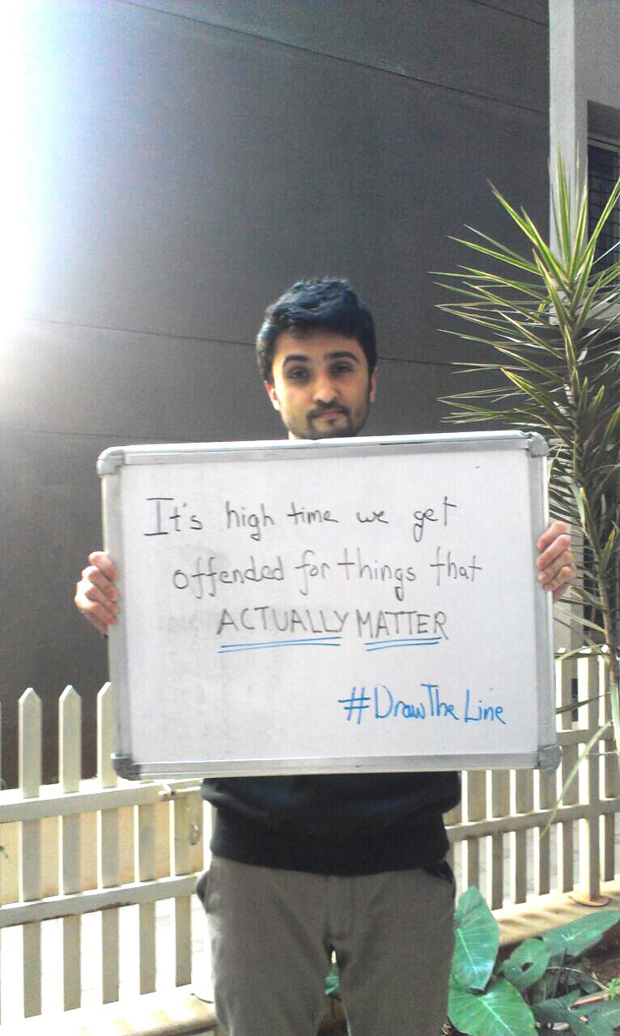

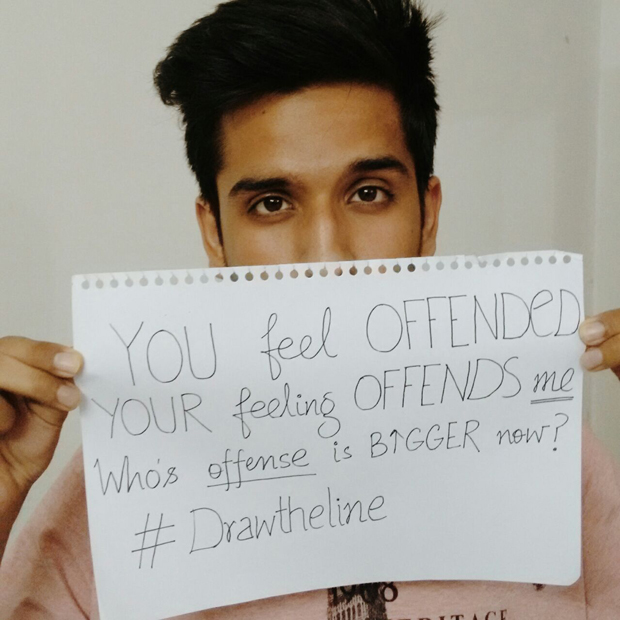

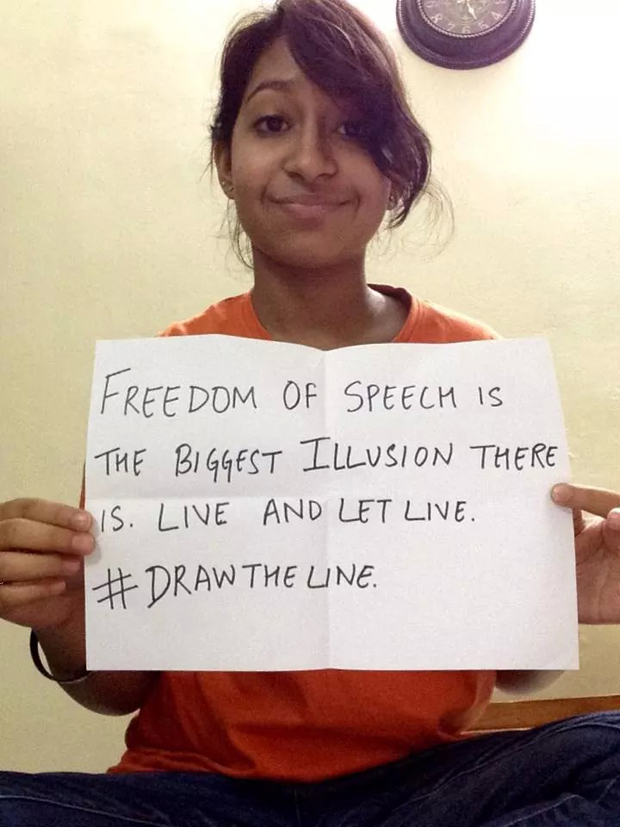

Below, are some young people from across India, who used photographs to join the #IndexDrawtheLine discussion. If you’d like to join the debate, tweet your photos or answers to #IndexDrawtheLine.

This article was posted on 16 February 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Feb 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Joshua Bonehill (Wikipedia user JoshuaBonehill92)

Joshua Bonehill is a national socialist, in an almost refreshingly old-fashioned way. When young Joshua speaks out against those who are destroying-our-society, undermining-our-culture, and so on, he does not equivocate with “neo-cons”, “internationalists” “bankers” or “global finance”. No, dear young Joshua comes straight out and says he’s against Jews (sometimes “the Jew”).

Bonehill hit the news this week after he said he would organise a march in Stamford Hill, north-east London on 22 March. Bonehill says his march is against the “Jewification” of Stamford Hill, to which one is tempted to answer “bit late, Joshua”. Stamford Hill is home to roughly 30,000 ultra-Orthodox Jewish people, mostly of the Haredi persuasion.

Bonehill is a keyboard Führer, an online agitator. His most notable “success” so far in his activist life has been spreading a false story about a pub in Leicester refusing to serve people in military uniform. The pub received threats of firebombing. Bonehill was convicted of malicious communications, though he escaped jail. He has a court appearance for similar offences lined up next week, and could quite conceivably go to prison for them, which would be a severe blow to his chances of rallying in Stamford Hill.

This hasn’t stopped a certain level of excitement spreading through social media (and indeed traditional media). Leftist and leftish friends on Facebook and Twitter have been excitedly discussing the prospect of Bonehill turning up on Clapton Common with hundreds of goons ready to make the borough of Hackney Judenfrei. In spite of his non-existent real world base, there is a very, very slight possibility that Bonehill could get more than a half-dozen. The Guardian points out that Bonehill has over 26,000 Twitter followers, “raising fears that even without a genuine political organisation behind him, his plan could draw in other far-right groups …”. To put that in slight perspective, I have a quarter of that number of Twitter followers, and can’t even muster people for an after work drink on a Friday evening, but then, I suppose I’m not trying to make a grab for the leadership of a scene that has been a mess since the collapse of the British National Party’s vote in the last European and local elections.

That is what Bonehill is getting at here. In his promotional YouTube videos for his march, he repeatedly calls for unity among “nationalists”. By targeting a Jewish area, he is hoping to rally the hardcore of British nationalism to his side; fascism’s attempt at populism, under Nick Griffin, had its thunder stolen by Ukip, and the hard core needs the reassurance of conspiracy theory and naked anti-Semitism.

Bonehill also appeals to his fellow racists’ sense of history, invoking the famous Battle of Cable Street, in which Oswald Mosley led the British Union of Fascists into (then Jewish area) Whitechapel and was met by local opposition from Jews, trades unionists and communists. Bonehill describes the 1936 rally as a “glorious victory”, which will come as a surprise to most leftists for whom Cable Street is shorthand for left virtue. (The Times’s Oliver Kamm has an interesting take on this.)

The memory of Cable Street is obviously looming large in the imagination of leftists and anti-fascists steeling themselves to organise against Bonehill. Cable Street is the universal good that everyone on the fractious left can share, and some would probably like to reenact it in some way in Stamford Hill, without necessarily working with the Jewish groups such as the Community Security Trust and the Shomrim, a community group Bonehill wrongly describes as a “Jewish Police Force”.

Cable Street was not the only time Mosley attempted to march in east London. Much later, in 1962, Mosley and his son Max (yes, that Max Mosley) were driven from the streets in Dalston, not far from Stamford Hill (watch this fantastic Pathe News footage).

So what is this then? Cable Street? Dalston? Even Skokie, Illinois, where the American Civil Liberties Union stood for the right of the American Nazi Party to march through a town populated by many Holocaust survivors (that march, in the end, never went ahead, but the position taken by the ACLU is often presented as a paragon of free speech principle, or bloodymindedness, or foolhardiness, depending who you talk to).

Bonehill has appealed to “the free speech community”– I’m guessing that’s you and me, dear reader – to stand with him, because “the Jews want us silenced” and his proposed protest has become “a battleground for free speech”. This is, of course, tosh. It is idiotic to conflate the support of free speech with the support of what people are saying. But that does not mean we could sit back and ignore this.

It would be wrong if Bonehill’s planned demonstration was banned in advance. Wrong because unpleasant though he is, he does have a right to protest and face counter protest (as did say, the EDL in areas with high Muslim populations), and wrong because it may lend a small bit of credibility to a deluded clown who may well be in jail by the time the appointed date comes round.

This column was posted on February 5, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

Does The Sun’s Page 3 still exist? The paper’s pagination remains, humble but resolute: the very best in British pagination. As surely as curry follows beer on this sceptered isle, the nation’s favourite newspaper will have a third page, facing the second page, on the reverse of the fourth. And despite what those who would disparage our way of life would want, it will always be page three.

Briefly, this week though, it seemed the tradition (est 1970), of putting a picture of a topless young woman on page three — the “Page 3 girl” — had ended. And then it came back. What’s going on? Is there a Page 3 or isn’t there? Or are we witnessing Shroedinger’s glamour shot?

The Page 3 girl was a typical product of the British sexual revolution. What started, with the availability of contraception to women in the 1960s, as a liberation, quickly became another way to reduce them. Freed from the terror of unwanted pregnancy, women and girls were now expected to be in a permanent state of up-for-it-ness. The popular films of the late 60s and early 70s, the On The Buses, the Carry Ons, the Confessions…, portrayed British society as a parade of priapic middle-aged men, always attempting to escape their middle-aged, old-fashioned wives, in pursuit of seemingly countless, always available, young women.

It was fun, it was cheeky, it was vampiric — depending on how you wanted to look at it.

Page 3 was part of this culture; this idea that sweet-natured young women with absolutely no qualms about sex were out there, just needing a wink and a Sid James cackle to persuade them into a bit of slap and tickle. Slap and tickle, though, is not the same as sex, or at least not sex as we might hope to understand it. The slap and tickle of the British imagination owes more to the pre-pill “sort of bargaining” described by Philip Larkin. In spite of the poet’s hopes, sexual intercourse hadn’t really begun in 1963.

Page 3 models were (are? Who knows?) very rarely erotic creatures. They were “healthy” and “fun”, perhaps a little “naughty”; always girls and never women.

The phenomenon survived the attentions of feminist campaigns of varying strengths. Page 3 perhaps peaked in the 80s, when it was possible to move beyond the tabloids to become an actual star, even with clothes on (80s Page 3 icon Sam Fox is still, apparently, in demand as a singer in eastern Europe). This, ironically, coincided with an era of politically correct criticism of Page 3 led by senior Labour MP Clare Short.

In the 90s, new laddism, spearheaded by James Brown’s Loaded magazine, somewhat rehabilitated the Page 3 girl, or, more accurately, made looking at topless models seem respectable to men who would never buy the Sun (“men who should know better” as Loaded’s tagline went).

As the post-Loaded rush for young men’s money descended into boasting of nipple counts, the focus of feminist campaigning switched to the weekly Nuts and Zoo magazines. The Sun’s Page 3 carried on, outliving the rise and fall of Nuts (somehow, Zoo is still going), but is now taking a severe battering from the No More Page 3 campaign, led by young feminists. The very fact that there is uncertainty over the future of the feature is testament to that campaign’s success.

It would be easy to look for a free speech angle on this and come up with “killjoy feminists” versus, decent honest yeomen of England.

But it would be false. In truth, what we have here is an example of how free speech works. The No More Page 3 campaign, as it has pointed out, has a right to call for an end to something they don’t like. They make the argument, they are criticised, and that’s absolutely fine. No one gets hurt, no one goes to court, no one tries to pass a prohibitive law (yet).

Meanwhile, there are some half-hearted defences floating around, mostly attempting to claim that Page 3 is a PROUD BRITISH INSTITUTION, like ugly dogs or barely suppressed tears.

“Tradition!”, the defenders shout, like a legion of leery, thigh-rubbing Topols. The Daily Star, which runs pictures of topless women on its own Page 3, but has escaped the ire of campaigners for the fundamental reason that no one really cares what’s in the Daily Star, proclaimed: “Page 3 is as British as roast beef and Yorkshire pud, fish and chips and seaside postcards. The Daily Star is about fun and cheering people up. And that will definitely continue!”. But really, it all seems a bit half-hearted.

Fundamentally, this week’s wind-up aside, The Sun’s topless Page 3 will cease to exist because people don’t really want it to exist, and no one can really think of a good reason for it to exist.

It’s not censorship, or prudishness, that will eventually kill Page 3. We’ve moved on, regardless of what the editors of The Sun do or say. It’s not them; it’s us.

This article was posted on 22 January, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org.