25 Oct 2018 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2018, News and features

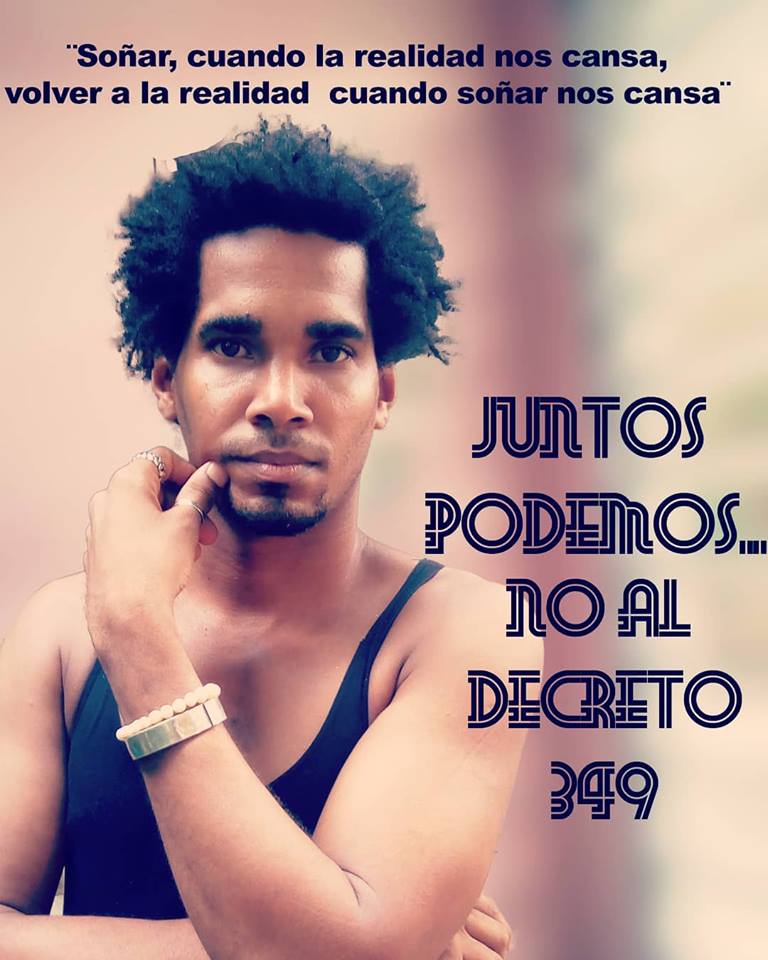

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”103471″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, a Cuban artist, and co-founder of award-winning Museum of Dissidence will perform in Trafalgar Square on 26 October 2018.

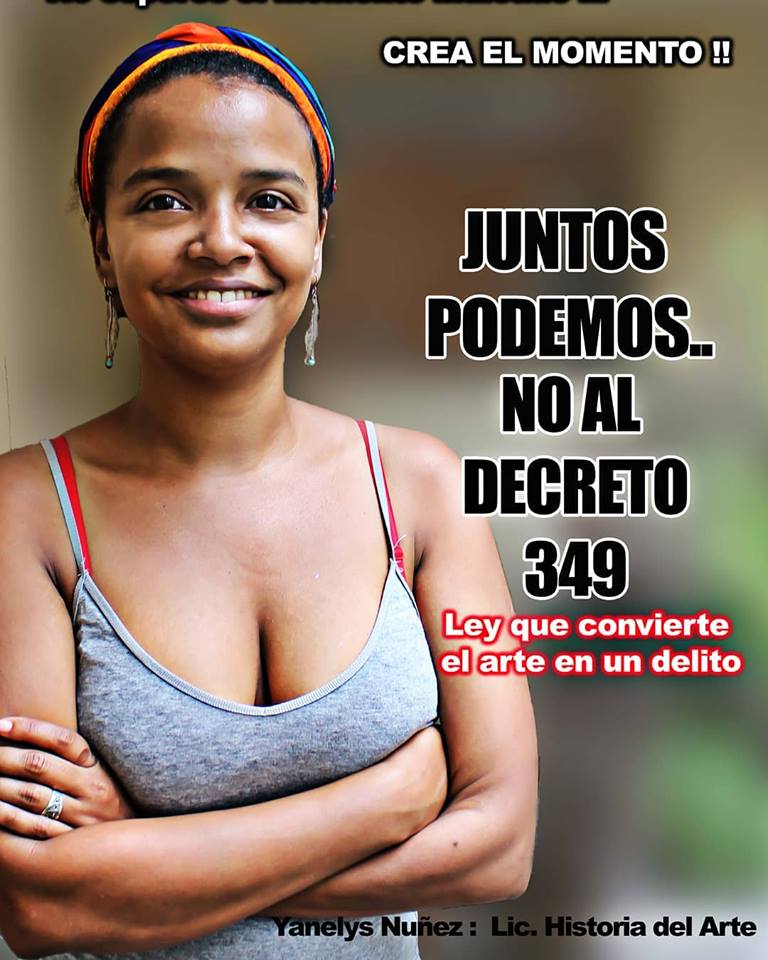

Along with art curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, they were hosted in Metal Southend for two weeks in October as part of a collaboration with Index. During their stay, they were presented their Freedom of Expression Award in the Arts category by Index which they could not formally accept in April due to visa refusal by the United Kingdom.

Otero Alcántara will be reproducing an artistic action that he exports to different cities, most recently performed in Madrid. His character, Miss Bienal, was created in 2016 and was present at all of the 2016 Havana Biennial exhibition*. The character intends to symbolise the image of the sensual mulatto woman that every foreigner typifies in clichés for tourist and artistic consumption. Dressed as a dancer from the famous Tropicana Cabaret and distributing business card to as many people as possible, where he had his personal contact details.

Miss Bienal is now visiting London and making the character his personal loudspeaker for the urgent need for artistic free expression in Cuba. Censorship on the island is becoming worse as there is a new decree 349 which will criminalise all cultural production that does not respond to the ideology of the state. Miss Bienal will have the number 349 on her costume and will be informing spectators about the limited freedom of expression in Cuba.

*This performance was part of the Hors-Pistes event: The Spring of Love, curated by Catherine Sicot (Elegoa Cultural Produtions) and Geraldine Gomez (Center Pompidou, Program Hors-Pistes).[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1540481508887-a7b0f0ee-6632-9″ taxonomies=”23772″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Oct 2018 | Artistic Freedom, News and features, Risks, Rights and Reputations

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”97076″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Agnieszka Kolek is curator and co-founder of Passion for Freedom, an annual competition exhibition of by artists facing censorship worldwide. In February 2015, Kolek survived the terrorist attack in Copenhagen, targeting the panel discussion she appeared in alongside Swedish artist Lars Vilks. Later that year in London, the Passion for Freedom 2015 exhibition at Mall Galleries, London, hit the headlines when a work Isis Threaten Sylvania by Mimsy was removed by the curators on the advice of the police. They had no choice because they couldn’t pay the £36,000 demanded by the police to guarantee security of the exhibition.

JF: How does your experience of the Danish police compare to the British police?

AK: The panel discussion — Art, Blasphemy and Freedom of Speech — was organised by the Lars Vilks Committee with the full support of the police. This was only a month after the Charlie Hebdo attack, but there was no question that the discussion should go ahead. There were two plain-clothed police officers, two uniformed police and then two special service officers responsible for Lars, who has 24-hour police protection. Police checked bags as the audience came in. When the attack happened — the Danish filmmaker Finn Nørgaard, one of the guests, was shot outside the venue and died on the pavement — the two special service officers took Lars to safety. We know that after an attack on freedom of speech the next target is Jews – it happened with Charlie Hebdo and it happened in Copenhagen when the same gunman attacked a bat mitzvah party in the evening, killing the security guard. Danes feel very bad that they didn’t anticipate this pattern and there was a lot of blaming of the police for this, but they did their best considering the circumstances. I think there has to be more legal power give to the police to extinguish the sources of the extremism, and its results. When you already have flames it is harder to put it, instead you have to prevent the fire from starting.

In London in 2015 it was very different. The police wanted to determine what artworks could go on show, and even the artistic value of exhibited works, showing an indirect form of censorship claiming it was “for your own good – security”. Police intelligence identified “serious concerns” regarding the “potentially inflammatory content” of Mimsy’s work and for this reason “advised” us to remove the work or pay protection money at £6,000 a day. We were completely shocked. Out of all the works in the exhibition, we would never have thought that they would pick this one out. We asked for more information about the “serious concerns”, especially because we wanted to know if there was a threat to Mimsy herself. They didn’t give us any more information. They wanted to place blame on the festival or its artists for causing problems, rather than protecting the space for art to show the suffering of people around the world and the lack of freedom to openly discuss it. While we tried to fundraise for our own protection, we were threatened with more works being withdrawn. Art cannot be controlled by the police – not in London, which for hundreds of years is a symbol of democracy and freedom. Not in the creative capital of Europe where artists flock from all over the world.

JF: But in Copenhagen two people lost their lives – you could have lost yours. How do you reconcile the loss of life with the pursuit of freedom?

AK: It is not easy to answer as I am not treating others’ and my own life lightly. Behind each individual there is a unique person, unique life story and to cut it short for the supposedly abstract ideal of free speech and expression might seem reckless. It is not. Again and again we learn how giving concessions to those who want to restrict freedoms of speech allows the darkness not only to enter our home but also our hearts. Not resisting it at early stages causes our societies to change beyond recognition.

I was invited to the Copenhagen event way ahead, so after the Charlie Hebdo attack, the chair got in touch with me to say she would understand in view of the heightened security risk, if I chose not to come. So I thought long and hard about it and said I will have to die someday, and I know I will look back at that this moment and I will remember the choice I made and it will be important.

Passion for Freedom is a very effective tool for assessing how much freedom there is in society. Artists cannot be easily controlled. In their inner core they are idealists. We stand with them giving them space and time to express themselves. Freedom will prevail despite political and corporate pressure to censor and restrict open debate. We are its guardians.

JF: How have the experiences of 2015 impacted on how you approach this year’s exhibition?

AK: The commitment and the conviction are still there. But we are not clear where we stand, because there is no clear definition of what is appropriate or what is inflammatory. It is a shifting ground. In the past, we created the space to fully exhibit work that had been censored elsewhere by a curator or a gallery owner. Now we are in the situation where the state, through the arm of the police, imposes this pre-emptive self-censorship on you. Since the censorship incident, we cannot guarantee artists that they will be able to exhibit/perform during a festival talking about freedom. Over the years there has been a number of artists who requested to be exhibited under pseudonyms (as often their lives are threatened in the UK or back in their home countries). Can we guarantee that the police will not arrest them? Until now, we could guarantee it to them. Since 2015 we are not sure that is the case. My approach is not to have any preconceived idea of how it will go with the police this time. We will still try to be open and have a dialogue in the belief that the police are still there to protect us and it is still a democratic country. I will be honest – we are also treating it as a kind of testing ground. Let’s see if this is still a democratic country or is it just on paper?

The artistic community in the United States and Australia is shocked by the police’s censorious attitude to arts in London. There are groups of people who decided to open Passion for Freedom branch offices in New York and Sydney to ensure that British censorship is being exposed. And in case freedom is completely extinguished in the UK they can continue the important work to give artists the platform to exhibit their works and debate important issues in our societies. And if we discover that there is even less freedom than in 2015, we are considering moving this exhibition to Poland because there is more freedom there. This is on the cards, we are already discussing it.

JF: Do you think Passion for Freedom exhibition represents a security risk?

AK: The way it is being framed in the media it looks like we are troublemakers and we are asking for it. I see it another way – we are representing the majority of society that wants to ask questions, to solve problems and to move forward together. Instead of giving in to a minority that wants to use violence and threats as a way to push forward their own agenda. I think it is in the interests of any society to make sure there is the space for difficult conversations because it moves away from creating the situation where the only way to solve problems is violence. You need to allow people to have this space and art is a wonderful tool to do that, without falling for propaganda, or just favouring one way of looking at things over another. Here you can have different voices, at different volumes, and different issues at play.

JF: The 2015 terror attack in Copenhagen targeted Swedish artist Lars Vilks and those who support him. Why do you think it is important for an artist to be free to deliberately insult and offend people’s religious beliefs?

AK: The world is a much more complex place than the newspaper headlines would like us to believe. Lars Vilks was invited to participate in an art exhibition on the theme “The Dog in Art” that was to be held in the small town of Tällerud in Värmland. Vilks submitted three pen and ink drawings on A4 paper depicting Muhammad as a roundabout dog. At this time, Vilks was already participating with drawings of Muhammad in another exhibition in Vestfossen, Norway, on the theme “Oh, My God”. Vilks has stated that his original intention with the drawings was to “examine the political correctness within the boundaries of the art community”. It is not a secret that Sweden is known for vehemently criticising the United States and Israel, whereas political Islam and its influence on non-Muslim communities are rarely questioned.

Artists practising various forms of art, whether poetry, drama, drawing or film, have been challenging those who hold power for millennia.

Few kings, warlords or dictators allowed criticism or satire of themselves. The blasphemy laws were in place not to protect God but those who claimed to be his only representatives on earth. Nowadays, the same seems to be disguised in the cloak of hurt feelings and delicate egos. Artists are idealistic visionaries. They cannot hold themselves back pretending that they are blind to what is in front of their eyes. Lack of open discussion stifles our development as societies. Fear of reprisal and death cripples the human spirit. Those who cower under the whip hoping to appease and remove the threat are actually risking the fate of a slave and subordinating to dehumanised serfdom their true nature – that of a free man.

JF: Why do you have this passion for freedom?

AK: Behind the Iron Curtain we naively believed that not only was the West this Land of Milk and Honey of material goods, we were also certain that there was freedom here, that people would value and protect it. So moving here, first you discover that everything is not so perfect materially, but then the bigger eye-opener is that there is always someone who wants to take freedom away and if you don’t stand up tall in society this threat is always present. I don’t think you can continue just exercising freedom of speech without appreciating what it has brought to us over the long years when previous generations were fighting for it, and though it is not ideal, the state we are in is much better than it used to be.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”103159″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Passion for Freedom Art Festival

10th-anniversary edition, 1 – 12 October 2018, London

The Royal Opera Arcade Gallery & La Galleria Pall Mall

Royal Opera Arcade, 5b Pall Mall, London SW1Y 4UY

The 10th-anniversary edition of internationally renowned Passion for Freedom Art Festival will open in London on 1 – 12 October 2018 at its new location – the Royal Opera Arcade Gallery & La Galleria Pall Mall. The exhibition showcases uncensored art from around the world, promoting human rights, highlighting injustice and celebrating artistic freedom.

Passion for Freedom was founded in 2008 and over the past ten years grew into an international network of artists, journalists, filmmakers and activists striving to celebrate and protect freedom of expression. We have displayed more than 600 artworks from 55 countries, including China, Iran and Venezuela.

The competition attracts much worldwide attention. This year, we received more than 200 submissions out of which we will exhibit over 50 shortlisted artists. From Venezuela to Turkey to the United Kingdom, those artists ceaselessly expose the restraints on freedom of speech, expression, and information in their countries. Altogether, we will display 100 such artworks during the festival. Passion for Freedom covers painting, photography, sculpture, performance, video, as well as authors, filmmakers and journalists.

Competitors will be judged by a prestigious selection panel. Winners will be announced on the 6th of October at the Gala Award Night.

This year’s judges are:

Andrew Stahl (United Kingdom)

Francisco Laranjo (Portugal)

Gary Hill (USA)

Lee Weinberg, PhD (Israel)

Mehdi-Georges Lahlou (Belgium)

Miriam Elia (United Kingdom)

Mychael Barratt PRE (Canada/United Kingdom)

This year we are thrilled to announce a Special Theo Van Gogh Award awarded in honour of his courage and contributions to freedom of expression.

Furthermore, we have invited a select group of special guest artists to display their latest works.

Passion for Freedom 2018 Guest Artists are:

Agata Strzalka (Poland)

Andreea Medar (Romania)

Emma Elliott (United Kingdom)

Jana Zimova (Czech Republic/Germany)

Mimsy (United Kingdom)

Öncü Hrant Gültekin (Turkey/Germany)

Oscar Olivares (Venezuela)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1539249597657-189331c4-e1af-0″ taxonomies=”15471, 8884″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Oct 2018 | Americas, Campaigns -- Featured, Cuba, Press Releases

Dates available for interview: October 17-29

LONDON – Two award-winning artists twice denied visas by the UK government this year finally arrive in the UK next week to take up a two-week residency.

The Museum of Dissidence collective, Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, winners of this year’s Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards for Arts will be in the UK from 17 to 29 October. They will take part in a two-week residency with Metal and accept their Index award in person. They were unable to attend the Index awards ceremony in April after the UK denied them a visa.

In May, the duo, along with other artists, organised Cuba’s first alternative art biennial. The independent biennial comprised over 170 independent artists, writers, musicians and theorists across nine different exhibitions in artists’ homes and studios around the country’s capital.

Since July, they have been active in a campaign against Decree 349, a new law in Cuba to be enacted on 1 December, which will give the Ministry of Culture increased power to censor, issue fines and confiscate materials for of which work they do not approve. On 21 July, Otero Alcantara was arrested during a peaceful protest, and, in early August, both were arrested ahead anti-censorship concert.

In September, a second application for a UK visa was rejected. However, the UK Embassy in Cuba later overturned their decision.

Both artists will be available for interview during their time here.

Contact:

Perla Hinojosa, Fellowships and Advocacy Officer

0207 963 7262

[email protected]

4 Sep 2018 | Bangladesh, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”102127″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]We, the undersigned hereby call for the immediate and unconditional release of the renowned photographer, artist, teacher, curator and human rights activist Shahidul Alam.

Dr Alam was arrested on 5 August 2018 by around 30-35 members of the detective branch of the Dhaka Metropolitan Police who dragged him away by force. Alam’s crime, we are told, is to have contravened the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act. Described as “draconian” by Human Rights Watch, the act has become an infamous means of clamping down on freedom of expression in Bangladesh.

Dr Alam has been accused of hurting “the image of the nation” through comments he made on social media and in an interview with Al Jazeera in which he was critical of the Bangladesh government. His observations were triggered by violence he witnessed towards students who gathered to protest in Dhaka after two of their number were killed by a speeding bus.

Given that Bangladesh presents itself as a democracy, the state should respect the right of Dr Alam, and all other citizens, to freedom of expression. Instead, he has suffered inhumane treatment at the hands of the police and judicial system.

The morning after his arrest, 6 August 2018, he was produced in court. Film footage shows police dragging him by his arms. He is barefoot, limping and struggling to walk. Both the film and reports from his lawyers who later met

with him in custody leave no doubt that he has been tortured. During his court appearance, he shouted to observers that he had been assaulted, forced to wear the same clothes after the blood had been washed from them, and

threatened with further violence if he didn’t testify as directed.

The court returned him to police custody ostensibly on a 7-day remand.

However, the day before he was officially due back in court, the judge sent him to prison. Neither Alam nor his lawyer was present at this hearing. His lawyer was not even informed that it was taking place.

Now he is being held in the Keraniganj Central Jail in Dhaka where conditions are extremely poor. After visiting him, his partner Rahnuma Ahmed called for medical attention as he was suffering from respiratory complications, problems with eyesight, and pain in his jaw. None of these symptoms were present before his arrest.

The brutal incarceration of Dr Alam is rooted in broader political repression. In recent years, Bangladesh has seen hundreds of citizens, including writers, intellectuals, lawyers and activists imprisoned and murdered. According to a

2017 report by Human Rights Watch, at least 320 citizens have been “disappeared” since the Awami League government came to power in 2009.

This situation has occurred despite the League’s pre-election pledge to react to human rights violations with zero tolerance. Dr Alam’s entire career has been devoted to combatting abuse of power. As a curator, artist and photographer, he has used images as the vehicle for decades of fearless truth-telling about subjects that include the genocide of the 1971 War of Liberation, the employment of state death squads and the plight of the Rohingya refugees. As the founder of picture agencies Drik and Majority World, and the photography school, Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, Dr Alam has also pioneered the wider practice of photo reportage in the region.

Little wonder he is admired throughout the world. In Britain, he has forged strong connections both through the presence of close family and through exhibitions at institutions including Tate Modern, the Whitechapel Gallery,

Autograph ABP, the Willmotte Gallery and Rich Mix. He has also run workshops, courses and other educational activities for young photographers in the British-Bengali community and beyond.

We now add our voices to the hundreds of others, from Nobel Laureates to Dr Alam’s own photography students, who in the last weeks have called for his immediate and unconditional release.

We also urge the Bangladesh government to respect the right to freedom of speech and expression for all citizens and to release all other prisoners detained on similar grounds.

1. Abu Jafar (Artist)

2. Alessio Antoniolli (Director, Gasworks & Triangle Network)

3. Anne McNeill (Director, Impressions Gallery, Bradford)

4. Anish Kapoor (Artist)

5. Akram Khan (Choreographer and Dancer)

6. Antony Gormley (Artist)

7. Assemble (art, architecture and design collective)

8. Ben Okri (Poet and Novelist)

9. Brett Rogers (Director, The Photographers’ Gallery)

10.Chantal Joffe (Artist)

11. Charlie Brooker (Writer and Producer)

12.David Sanderson (Arts Correspondent, The Times)

13.Fiona Bradley (Director, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh)

14.Frances Morris (Director, Tate)

15.Hans Ulrich Obrist (Artistic director, Serpentine Gallery)

16.Helen Cammock (Artist)

17.Iwona Blazwick (Director, Whitechapel Gallery)

18.Jodie Ginsberg (CEO Index on Censorship)

19.Joe Scotland (Director, Studio Voltaire, London)

20.John Akomfrah (Artist)

21.Sir John Leighton (Director, National Galleries of Scotland)

22.Jonathan Watkins (Director, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham)

23.Konnie Huq (Writer and Broadcaster)

24.Louisa Buck (The Art Newspaper)

25.Lubaina Himid (Artist)

26.Mahtab Hussain (Photographer)

27.Dr Mark Sealy MBE (Director of Autograph ABP)

28.Mark Wallinger (Artist)

29.Martin Parr (Photographer and Photojournalist)

30.Michael Landy (Artist)

31.Michael Mack (Founder of publisher MACK)

32.Nadav Kander (Artist)

33.Neel Mukherjee (Writer)

34.Nicholas Cullinan (Director, National Portrait Gallery)

35.Nick Serota (Chair of Arts Council England)

36.Olivia Laing (Writer)

37.Pippa Oldfield (Impressions Gallery, Bradford)

38.Polly Staple (Director Chisenhale Gallery)

39.Rachel Spence (Poet and Arts Writer, Financial Times)

40.Rana Begum (Artist)

41.Rasheed Araeen (Artist)

42.Sally Tallant (Director, Liverpool Biennial)

43.Sarah Munro (Director Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art)

44.Sophie Wright (Global Cultural Director, Magnum Photos)

45.Steve McQueen (artist and film director)

46.Sunil Gupta (Photographer)

47.Teresa Gleadow (Curator, Writer and Editor)

48.Vicken Parsons (Artist)

49.Dr. Ziba Ardalan (Founder/ Director Parasol unit, London)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1536055987310-fa96858b-d48c-8″ taxonomies=”6534″][/vc_column][/vc_row]