Free speech in India: Uptick in defamation, attacks on media cause for concern

The state of free speech in India remains a cause for concern judging by the rise in recorded attacks on the media and the increasing use of defamation suits — the most marked trends in 2014.

The figure for attacks on the media rose sharply with better data collection. There were at least 85 attacks this year. For the first time, since January 2014, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) has begun collecting data on attacks on the media as a separate category.

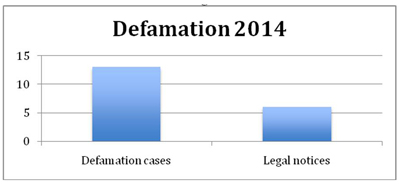

Reported cases of defamation and legal notices alleging defamation totaled 21 in 2014 (till December 15). Of the eleven new cases recorded, seven were filed against media, two against college publications, and 3 against individual politicians. Two were court orders against publishers, a total of 14. Those against the media included the cases filed by Justice Swatanter Kumar and Indian captain M.S. Dhoni; politician Gurudas Kamat, and the Sahara Group.

In addition, one defamation conviction was upheld in a case filed earlier, against Vir Sanghvi when he was at the Hindustan Times.

Seven legal notices were served during the year — five to media houses, one to a marketing federation for the advertisement they ran, and one to journalist-authors. The last was sent by Mukesh Ambani-led Reliance Industries Ltd to Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and other authors of the book Gas Wars: Crony capitalism and the Ambanis. A Rs 100 crore notice was sent by industrialist Sai Rama Krishna Karuturi, Managing Director of Karuturi Global Ltd, to environmental journalist Keya Acharya. Infosys, and a former police commissioner in Pune also served legal notices on the media in the year gone by.

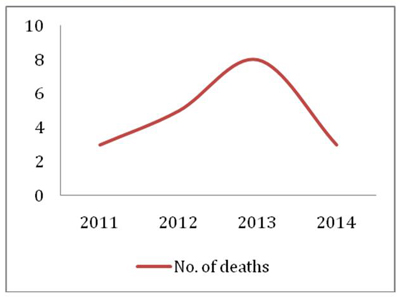

There was a drop in the deaths of journalists from eight in 2013 to two this year. However, a hate crime was recorded in the death of a software engineer in Pune, underlining the spike in hate speech cases. Apart from censorship across media and of books, theatre and film, there were at least 85 cases of attacks on journalists, 62 of which were from Uttar Pradesh alone.

These and other instances form part of the reported cases in the Free Speech Tracker of the Free Speech Hub till December 15, 2014. A project of the media watch site The Hoot the Free Speech Hub has been monitoring freedom of expression in India since 2010 and this is its fifth annual report. The tracker looks at a range of issues, including journalists’ deaths, attacks on journalists and on citizens, threats and arrests arising out of free speech issues, censorship, defamation, privacy, contempt, surveillance, and hate speech.

Seven defamation notices, and six legal notices were against media houses or journalists. In addition police complaints alleging defamation were also filed. The defamation cases also resulted in gag orders against the media, drawing criticism from the Editors Guild of India but to no avail. A defamation case filed by former President of the BJP, Nitin Gadkari also resulted in the arrest of Aam Aadmi Party leader Arvind Kejriwal in May, for calling the former corrupt. Kejriwal refused to furnish a bail bond and was remanded to judicial custody. The latest case, a Delhi police directive to radio stations to stop broadcasting a jingle from the Aam Aadmi Party on the grounds of defamation, only served to illustrate the extreme sensitivity of the powers that be to any criticism.

Clearly, defamation cases act as a pressure and silencing tool. Congress spokesperson and former minister Manish Tiwari faced arrest in a criminal defamation case filed by former BJP President Nitin Gadkari for alleging that the latter held a ‘benami’ flat in the Adarsh housing society. But after a summons was issued for his arrest, Tiwari submitted an unconditional apology and the case was withdrawn.

In another case, the Sahara media group filed a defamation case against Mint editor Tamal Bandopadhyay and the Kolkata High Court stayed the release of his book, Sahara: The Untold Story but a disclaimer and a settlement followed and the case was withdrawn.

Hate speech remains on the fault lines of free speech and, given the unabashed use of hate propaganda during the campaign for the 16th Lok Sabha elections, there was a sharp spike in the number of hate speech cases to 20 this year, double the 2013 figure.

The arrest of people for Facebook posts continued, despite clear guidelines issued on cases related to Section 66 (A) of the Information Technology Act in the wake of the arrest of two students from Palghar in 2012 and a pending case challenging the provisions before the Supreme Court of India. Sedition cases also cropped up; a student was arrested in Kerala for sedition for remaining seated while the national anthem was being played in a cinema.

Apart from the ignominious cave in by book publishers to the demands of Hindutva organisations, as in the case of the Wendy Doniger book The Hindus, other attacks on the media and civil society activists and violence by vigilante groups bent on imposing a regressive moral agenda, added to the potent brew for free speech violations in 2014.

Highlights

Deaths : Two journalists and a victim of a hate crime

There has been a drop in the deaths of journalists from eight in 2013 to two this year. Tarun Acharya in Odisha and M.N.V. Shankar in Andhra Pradesh were brutally killed days after reporting on malpractices by local business people.

The third death, of 24-year old Mohsin Shaikh, a software engineer in Pune, was triggered by a Facebook post allegedly defamatory to 17th century Maratha ruler Shivaji and the late Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray. The engineer had no connection with the Facebook post but was targeted because his beard indicated his identity as a Muslim. Police arrested the founder of the Hindu Rashtra Sena, Dhananjay Desai, for a hate crime.

In 2013, eight journalists died, including Sai Reddy who was killed by Maoist groups in Chhattisgarh. In April 2014, these groups admitted that killing Reddy was a mistake. There were five deaths in 2012 and three in 2011.

Defamation cases and legal notices increase to 21

Defamation cases and legal notices threatening defamation had a chilling effect on freedom of expression with 21 instances being recorded through the year, an increase from the two cases in 2012 and seven in 2013. From politicians to business houses, lawyers, former judges and media houses, defamation notices were sent against book publishers, advertisers, other media houses and journalists.

Arrest of 13 persons, including a journalist under NSA, a student for sedition and three persons for Facebook-related content

In Kerala, nine students were arrested for a crossword clue in a college magazine allegedly unfavourable to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Other arrests included a journalist from Assam, allegedly due to links with insurgency groups and a student from Kerala on charges of sedition for remaining seated while the national anthem was being played in a cinema and three others for Facebook-related content.

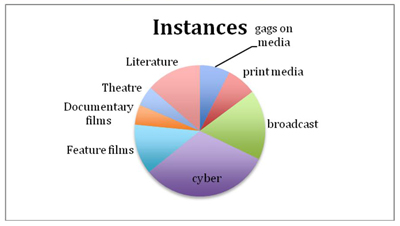

Censorship: 85 instances

The number of instances of censorship this year fell to 86 from 99 in 2013 and 74 in 2012. Internet-related censorship fell marginally from 32 in 2013 to 27 this year. Ten of these instances were related to Facebook posts that attracted cases and triggered violence in at least three instances. There were 25 instances of censorship in print and the broadcast media, including five gag orders on media reportage and one on radio broadcasts of an advertisement.

Censorship showed an overall decrease from 99 instances last year to 85 this year. However, censorship in the broadcast media saw an increase to 14 instances, besides five instances of gags on media coverage of sensitive issues being obtained by a range of people, including former judges charged with sexual harassment and sports bodies and educational institutions.

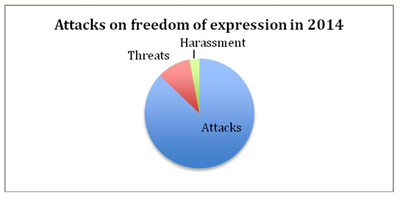

Attacks, threats and harassment: 101 instances

Direct physical attacks on the media and on citizens for freedom of expression issues remained high, with at least 85 cases of attacks recorded by the media alone in 2014. In addition, there were three attacks on other citizens, ten cases of threats and three of harassment.

For the first time, the National Crime Records Bureau has begun collecting data on attacks on the media as a separate category from January this year. In a written reply to a question in the Lok Sabha, the Minister of State for Information and Broadcasting Rajyavardhan Rathore said that, up to June, 62 of these cases occurred in Uttar Pradesh.

According to the Minister’s reply, up to August 8, there were six cases each in Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, with no arrests in Bihar but eight in Madhya Pradesh. Cases of attacks on the media were also registered in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Assam and Meghalaya and seven people were arrested in connection with the cases in Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Meghalaya.

While more details are awaited on these attacks and on how many were related to professional work, the Hoot’s Free Speech Tracker has details of 18 instances of attacks and 12 instances of threats recorded this year. Of these, 15 attacks and nine threats were directed at the media, including a police assault on journalists covering news events, the sand mafia attacking an environmental journalist, separate instances of a petrol bomb and gunshots fired on the homes of journalists and reports of journalists being used as ‘human shields’ in Kashmir.

Sharp spike in hate speeches

This year saw the sharpest rise in hate speeches from two in 2012 and ten in 2013 to 22, peaking in the run-up to what was billed as the most divisive general election in India’s history. Apart from riots that broke out due to the circulation of videos or inflammatory messages, instances of hate propaganda and riots marked the increase in hate speeches in the country and, given the scheduled elections to various state assemblies, shows no signs of abating till the end of the year — witness the reports of the hate speech made by BJP Minister Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti in December 2014.

Snapshot of the last three years

| Categories | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 |

| Deaths of journalists Death due to hate crimeTotal |

02 0103 |

08

|

05 |

| Attacks on the media Attacks on citizens Threats Harassment Arrests/detentionsTotal |

85 03 10 03 04105 |

20 04 0225 |

39

|

| Censorship :

Gags on all media Music Total |

06 06 14 26 10 04 04 – 0511 86 |

15

11 07 99 |

08

04 07 74 |

| Privacy & Surveillance | 08 | 13 | 05 |

| Defamation cases Legal notices Court order Total |

12 07 0221 |

07 | 02 |

| Hate speech Hate propagandaCourt cases on hate speech restrictions |

20 0202 |

10 | 02 |

| Policy, regulation | 02 | 07 | 03 |

| Sedition (including three withdrawals) Contempt Legislative privileges |

05 03 |

02 02 01 |

The year in review

Free speech violations in 2014 included the death of two journalists for their investigative stories on malpractices in local businesses, the killing of a young software engineer in Pune for what police termed a ‘hate crime’, an increase in defamation cases and legal notices to curb reportage of a range of issues, increasing attacks on the media and civil society activists, violence by vigilante groups and a spike in hate speech cases during various election campaigns.

While the number of deaths of journalists for their work may have fallen from the eight of the preceding year to two this year — Tarun Acharya and M.N.V. Shankar – they underline the extreme vulnerability of journalists working in small towns, particularly on unearthing crimes.

Acharya, 29, was a stringer for Kanak TV in Odisha and was killed on May 27 in Khallikote town of Ganjam district. He had done an investigative story on the alleged employment of children in a cashew processing plant owned by one S. Prusty. Shankar, 52, a senior correspondent with Andhra Prabha newspaper, was killed in Chilakaluripet town of Guntur district on May 26, a few days after his newspaper published his report on the kerosene oil mafia. While the police arrested two persons in connection with Acharya’s murder, Shankar’s killers have yet to be found.

Attacks, arrests

This year saw an increase in attacks on the media, as officially recorded by the National Crimes Bureau for the first time, an increase in threats to journalists as well as the arrests of journalists for alleged involvement with insurgency groups and the arrest of citizens for posts on social media.

Of the eight cases linked to Facebook posts, one person was arrested for a post allegedly against West Bengal Chief Minister Mamta Banerjee; an Aam Aadmi Party activist was arrested for forwarding an allegedly anti-Modi text in Karnataka; a student was arrested for allegedly mocking the national anthem in Kumta, Karnataka; and in Kerala, a student was arrested for sedition for allegedly insulting the national anthem by remaining seated while it was being played in a local theatre.

Defamation

The intimidating effect of a possible defamation suit was clearly on the rise as 2014 recorded 21 instances of defamation against individuals and the media. These included 13 cases of defamation and six legal notices, besides one court order.

In May, Aam Aadmi Party leader Arvind Kejriwal was arrested in a defamation case filed by former president of the BJP, Nitin Gadkari, for calling the latter corrupt. He refused to furnish a bail bond and was remanded to judicial custody.

Former Supreme Court judge and National Green Tribunal Chairperson Justice Swatanter Kumar filed a defamation case against two English television channels and a leading English newspaper as well as a law intern who had filed a complaint of sexual harassment against him. He also managed to get a gag order on media reportage of the case.

In another case, India cricket captain M.S. Dhoni filed a Rs 100 crore defamation case in the Madras High Court against media houses Zee Media Corporation and News Nation Network over allegations of his involvement in match-fixing.

Clearly, defamation cases serve to silence people. Congress spokesperson and former minister Manish Tiwari faced arrest in a criminal defamation case filed by former BJP President Nitin Gadkari for alleging that the latter held a ‘benami’ flat in the Adarsh housing society. But after a summons was issued for his arrest, Tiwari submitted an unconditional apology and the case was withdrawn.

In another case, the Sahara media group filed a defamation case against Mint editor Tamal Bandopadhyay and the Kolkata High Court stayed the release of his book, Sahara: The Untold Story, but a disclaimer and a settlement followed and the case was withdrawn. Given that decriminalizing defamation has been a long-standing demand of journalists’ organisations, it is ironical that a media group such as Sahara should resort to defamation notices.

It was not the only one. India TV sent a defamation notice to aggrieved employee Tanu Sharma who had alleged sexual harassment and had attempted suicide outside the company’s office. It also sent a defamation notice to media watch site Newslaundry which carried a report on the incident.

Among the other cases, Infosys sent notices of Rs 2000 crore each to three publications owned by Bennett, Coleman and Co. Ltd and The Indian Express Ltd. Other multi-crore defamation notices included separate notices sent by Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries Ltd and Anil Ambani-led Reliance Natural Resources Ltd to journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, author of Gas Wars: Crony Capitalism and the Ambanis. The notices were an attempt to remove the self-published book from the website promoting it.

An Inter Press Service story by environmental journalist Keya Acharya on the legal, financial, tax, labour and land problems of the Ramakrishna Karuturi-owned Karuturi Global Limited in Kenya and Ethiopia attracted a Rs 100 crore defamation notice.

Censorship

Censorship showed an overall decrease from 99 instances last year to 86 instances this year. However, censorship in the broadcast media saw an increase to 14 instances, besides five instances of gags on media coverage of sensitive issues being obtained by a range of people, including former judges charged with sexual harassment and sports bodies and educational institutions. A gag on radio jingles by Delhi police was the latest attempt at censorship.

An increase in censorship was also recorded in the arena of literature and non-fiction books, including in academia. In February 2014, Penguin, the publishers of The Hindus: An Alternative Histor, by the well-known Indologist Wendy Doniger, decided to pulp all remaining copies of the book in an out-of-court settlement with Shiksha Bachao Andolan (SBA), which had filed a civil suit against the publishers in 2011.

The organization, headed by Dinanath Batra, targeted other publishers and Orient Blackswan followed suit to withdraw ‘Communalism and Sexual Violence: Ahmedabad since 1969’ by Dr Megha Kumar. The same publisher also put under review Sekhar Bandyopadhyay’s book From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India.

In 2008, SBA was instrumental in filing a complaint before the Delhi High Court seeking the withdrawal of A. K. Ramanujam’s essay, Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translations, from Delhi University’s history syllabus. In July 2014, following the election victory of the BJP, six of Batra’s books were prescribed as compulsory reading as supplementary literature in the Gujarat state curriculum.

Hate speech

Over the last few years, hate speech and hate propaganda have tested the limits to free speech. The Free Speech Tracker has recorded two instances of hate speech in 2012 and ten in 2013. By 2014, the number of hate speech cases doubled, with an additional complaint of hate campaigning.

The death of an innocent software techie, Mohsin Sadiq Shaikh, 24, at the hands of members of a Hindu fundamentalist group, the Hindu Rashtra Sena in Pune on June 4, was a chilling reminder of the violent consequences of hate propaganda. A Facebook post with allegedly derogatory photographs of 17th century Maratha ruler Shivaji and the late Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray had triggered violence in Pune and a mob chanced upon Shaikh and his friend, returning home after offering namaz. Shaikh, who was identified as a Muslim by the skull cap he wore, was beaten to death. Later, seven members of the organization, including its leader, Dhananjay Desai, were arrested and charged with his murder.

Other hate speech cases were recorded throughout the year, beginning with the general election campaign and continuing to the end of the year with a lawyer from Mumbai being charged with posting allegedly inflammatory content on Facebook and BJP MP Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti making offensive remarks on December 3.

Prominent leaders of political parties, including BJP President Amit Shah, were booked for hate speech. Other political leaders charged with hate speech included Pravin Togadia (VHP), Ramdas Kadam (Shiv Sena), Giriraj Singh, Baba Ramdev, Tapas Pal (Trinamool Congress), Azam Khan (Samajwadi Party), Pramod Mutalik (Sri Ram Sene), Imran Masood and Amaresh Mishra (Congress-I).

Contempt, privacy and surveillance

Contempt cases continued to come up and three instances were recorded, including one case that cited the archaic provision of ‘scandalising the court.

Instances of privacy also continued to figure on the Free Speech Tracker as business people and social activists cited privacy concerns to stall books and films based on their lives. In the latter category, Gulabi Gang founder Sampat Pal sought a stay on a Bollywood feature film based on her life on the grounds of privacy and copyright but settled out of court. And the Bombay High Court directed the makers of a film based on the Khairlanji massacre to apply for a fresh certificate from the Central Board of Film Certification.

Surveillance, a growing issue both globally and nationally, remained a concern as the new government reiterated its plans to go ahead with the UPA’s controversial UID scheme even as it quietly continued the roll out of the surveillance programmes of the previous regime.

For a detailed list of the instances from the Free Speech Tracker, please click here.

This article was originally posted on 16 Dec 2014 at thehoot.org and is posted here with permission.