30 Jan 2017 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Letters, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

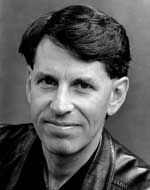

Ilgar Mammadov

Azerbaijani opposition politician Ilgar Mammadov was jailed in 2013. The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled in May 2014 that Mammadov’s arrest and continued detention was in retaliation for criticising the country’s government.

Mammadov is a leader of the Republican Alternative Movement (REAL), which he launched in 2009, and is one of Azerbaijan’s rare dissenting political voices. He was sentenced to seven years in prison after participating in an anti-government protest rally in Ismayilli, a town 200 kilometers outside Baku. Authorities arrested him on trumped-up charges of inciting the protest with the use of violence. Mammadov had previously announced his intent to run for president. Mammadov remains in jail, despite the Council of Europe repeatedly calling for his release. Azerbaijan may be expelled from the council as the country repeatedly refuses to comply with the organization’s requests. John Kirby, spokesman of the US Department of State, also called on Azerbaijan to drop all charges against Mammadov. Reports in November 2015 emerged stating that Mammadov had been tortured by prison officials, which resulted in serious injuries including broken teeth. Mammadov has remained very vocal during his time in jail, writing on his blog about political developments in Azerbaijan and refusing to write a letter asking for pardon from President Ilham Aliyev.

The following is a letter written by Ilgar Mammadov:

International investment in fossil fuel extraction is making me and other Azerbaijani political prisoners hostages to the Aliyev regime.

A thirst for freedom.

Azerbaijan has seen a crackdown on any political dissent over the past few years, with dozens of activists and critics of the regime in Baku going behind bars. So far, there’s little sign of improvement.

Though respectful of the memory of Nelson Mandela, the mass media have occasionally shed light on the late South African leader’s warm relationship with scoundrels such as Muammar Qaddafi and Fidel Castro, as well as his refusal to defend Chinese dissidents. These events have been evoked to invite critical thinking about an iconic figure and balance his place in history.

Most readers of these articles judge a figure they previously held as an idol as hypocritical or tainted. They do not ask questions about the roots of a particular contradiction. In the case of Mandela, the dictators above had supported the anti-apartheid struggle of the African National Congress, while several established democracies indulged the inhuman system of apartheid because of the diamond, oil and other industries, and particularly because of the Cold War.

After only four years in prison, even on bogus charges and a politically motivated sentence, I am nowhere near Mandela in terms of symbolising a cause of global significance. Republicanism in my country, Azerbaijan — where the internationally promoted father-to-son succession of absolute power has disillusioned millions — is hardly comparable to the fight against racial segregation. Still, I can, better than many others, explain the flawed international attitudes that help keep democrats locked in the prisons of the “clever autocrats” who are, in turn, courted by retrograde forces within today’s democracies.

I will tell the story of how plans for a giant pipeline that would suck gas from Azerbaijan to Italy, the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), impacts on Azerbaijan’s political prisoners.

In this letter I will focus only on one tension of the struggle we face here in Azerbaijan — between our democratic aspirations that enjoy only a nominal solidarity abroad, and the attempt to build a de facto monarchy which receives comprehensive support from foreign interest groups.

To be precise, I will tell the story of how plans for a giant pipeline that would suck gas from Azerbaijan to Italy, the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), impacts on Azerbaijan’s political prisoners.

I will tell the story by discussing my own case. But before I tell it, you need to know what the Southern Gas Corridor is and why my release is crucial for the morale of our democratic forces. Indeed, Council of Europe officials say my freedom is essential for the entire architecture of protection under the European Convention of Human Rights, but there is still no punishment of my jailer.

What is the Southern Gas Corridor?

The Southern Gas Corridor is a multinational piece of gas infrastructure worth $43 billion US dollars. It is designed to extract and pump 16 billion cubic metres of natural gas every year from 2018, sucking hydrocarbons from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz gas field to European and Turkish markets. The EU, Turkey, and the US are all eager to connect the pipeline to Turkmenistan so that to an extra 20-30 billion cubic metres of Turkmen gas can be added to the scheme.

Hydrocarbon extraction is the mainstay of the country’s economy. Baku signed the “contract of the century” in 1994, and has attracted western oil and gas giants ever since.

The significance of the SGC is twofold. First, the project could provide up to 8-10% of EU’s gas imports, thus reducing the union’s dependence on Russia. Secondly, it will become another platform for geopolitical access (Russians would use a slightly ominous word “penetration”) of the west to Central Asia.

How did SGC encourage more repression?

Any rational democratic government in Baku would opt for the SGC without much debate and then turn its attention to issues truly important for Azerbaijan’s sustainable economic development. The revenue generated by the project would not be viewed as vital for the country when compared to the country’s economic potential in a less monopolised and more competition-based economy.

However, since the moment when a Russian government plane took Ilham Aliyev’s barely breathing father from a Turkish military hospital to the best clinic in America, in order to smooth the transition of power, the absolute ruler of Azerbaijan has been trained to deal with great powers first and then use such deals to repress domestic political dissent second. He has kept the country’s economy almost exclusively based on selling oil and gas and importing everything else.

Recently, Aliyev has been trying to present the SGC as his generous gift to the west so that governments will not talk about human rights and democracy in Azerbaijan. At one point Aliyev was even considering unilaterally funding the entire project.

Since 2013, Aliyev has instigated an unprecedented wave of attacks on civil society, which he used to illustrate the seriousness of his ambition for energy cooperation with the west.

In the middle of this tug of war, Azerbaijan suddenly found itself short of money due to falling oil prices. It could not fund its share in the parts of SGC that ran through Turkey (TANAP) and Greece, Albania and Italy (TAP) without backing from four leading international financial institutions — the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, European Investment Bank, World Bank and Asian Development Bank.

During 2016, these institutions said their backing was subject to Azerbaijan’s compliance with the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI). In September, Riccardo Puliti, director on energy and natural resources at the EBRD, cited the resumption of the EITI membership of Azerbaijan as “the main factor” for the prospect of approval of funds for TANAP/TAP.

Together with EIB, EBRD wants to cover US $2.16 billion out of the total US $8.6 billion cost of the TANAP. TAP will cost US $6.2 billion.

What is the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative?

The EITI is a joint global initiative of governments, extractive industries, and local and international civil society organisations that aims, inter alia, to verify the amount of natural resources extracted by (mostly international) corporations and how much of the latters’ revenue is shared with host states. Its purpose, in that respect, is to safeguard transnational businesses from future claims that they have ransacked a developing nation — for instance, by sponsoring a political regime unfriendly to civil society and principle freedoms.

In April 2015, because of the unprecedented crackdown on civil society during 2013-2014, the EITI Board lowered the status of Azerbaijan in the initiative from “member” to “candidate”. This move, alongside falling oil prices, complicated funding for the Southern Gas Corridor. International backers were reluctant to be associated with the poor ethics of implementing energy projects in a country where already fragmented liberties were degenerating even further.

Hence, during 2016, several governments, especially the US, put strong political pressure on Azerbaijan. This resulted in a minor retreat by the dictatorship. Some interest groups claimed at the EITI board that this was “progress”.

The EITI board assembled on 25 October to review Azerbaijan’s situation. I appealed to the board ahead of its meeting.

Why did my appeal matter?

My appeal was heard primarily because, until I was arrested in March 2013, I was a member of the Advisory Board of what is now the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), a key international civil society segment of EITI.

In addition to my status within the EITI, the circumstances of my case — which was unusually embarrassing for the authorities — also played a role:

i) The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) had established that the true reason behind the 12 court decisions (by a total of 19 judges) for my arrest and continued detention was the wish of the authorities “to silence me” for criticising the government;

ii) The US embassy in Azerbaijan had spent an immense amount of man-hours observing all 30 sessions of my trial during five months in a remote town and concluded: “the verdict was not based on evidence, and was politically motivated”;

iii) The European Parliament’s June 2013 resolution, which carried my name in its title, had called for my immediate and unconditional release — a call reiterated in the next two EP resolutions of 2014 and 2015 on human rights situation in Azerbaijan;

iv) Since December 2014, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe had adopted eight (now nine) resolutions and decisions specifically on my case whereby it insisted on urgent release in line with the ECHR judgment.

Due to an onslaught by civil society partners during the 25 October debate, the EITI Board refused to return Azerbaijan its “member” status.

Indecision in America

I am very much obliged to the US embassy for conducting the hard labour of trial observation, but the US government representative’s stance at the EITI board meeting in October was a surprising disappointment.

Mary Warlick, the representative of the US government, insisted that Azerbaijan has made progress worth of being rewarded by EITI membership. Obviously, she was speaking for that part of the US government that wants the SGC pipeline to be built at any cost to our freedom.

A month later, in a counter-balancing act, John Kirby, spokesman of the US Department of State, called on Azerbaijan to drop all charges against me.

Samantha Power’s Facebook posting of my family photo on 10 December, the International day of Human Rights, was also touching. Power is US Permanent Representative at UN. Two years ago, she already mentioned my case in the EITI context at a conference.

Complementing her kindness, around the same time Christopher Smith, Chairman of the Helsinki Commission of the US Congress, in an interview about fresh draconian laws restricting free speech in Azerbaijan, repeated his one year old call for my release.

Yet, on 15 December, Amos Hochstein, US State Department’s Special Envoy on Energy, assured the authorities in Baku that “regardless of any political changes, the US will remain committed to its obligations under the SGC”.

Indecision in Europe

I could set out a similar pattern of European hesitation beginning with my first days in jail.

To be concise, though, let me recall only the fact that on 20 September (the same day that Rodrigo Duterte called the European Parliament “hypocritical” for its criticism of the extra-judicial executions in Philippines), a conciliatory delegation of the EP in Baku not only agreed to hear a lecture from Ilham Aliyev on “[EP] President Martin Schultz and his deputy Lubarek being enemies of the people of Azerbaijan”, but even praised the lecture as a “constructive one”, in the words of Sajjad Karim, the British MEP who had led the delegation.

Political prisoners of Azerbaijan are not worth the amount of money involved in the SGC, but European values probably are.

The aforementioned three resolutions of the European Parliament were thus crossed out as I observed from behind bars.

Two presidents of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council Of Europe (PACE) have visited me in prison, but this only highlighted the irrelevance of the body to the situation on the ground. They never stopped talking of how constructive or how ongoing their dialogue with the Azerbaijani authorities has been.

New threats

Our narrow win at the EITI Board exposes us to two new threats. (I do not discuss here the extraneous threats, which may originate from, for example, rising oil prices or collapse of the nuclear deal with Iran, i.e. anything adding confidence or bargaining power to the regime in Baku.)

One is that at the next EITI board meeting in March 2017, those driven by pressing commodity and geopolitical interests may outnumber or otherwise outpower the civil society party. If Ilham Aliyev proceeds with his cosmetic, fig leaf “reforms” or releases those political prisoners who have already pleaded for pardon or surrendered in any other way, the probability of my freedom being sacrificed will arise again.

The other threat is that instead of battling at the EITI, those interest groups may ask the international financial institutions to disconnect the SGC loans from Azerbaijan’s compliance with the EITI. These institutions are easier to convince as they are full of short-termist bank executives, rather than civil society activists concerned with the rule of law, transparency and public accountability.

The second scenario may already be in effect as rumours suggest that the World Bank has endorsed a US $800m loan to the TANAP. If so, then the postponed energy consultations between Baku and Brussels at the end of January may put the loans back on the EITI-friendly track. Political prisoners of Azerbaijan are not worth of the amount of money involved in the SGC, but European values probably are.

Deep jail horizon

Of 11 other members of the ruling body of my civic movement, REAL, three had to flee the country after my arrest, two were jailed (for 1.5 years and one month on charges not related to my case), two are not permitted to travel abroad (again on separate cases); one of them cannot even leave Baku.

From time to time, activists spend days under administrative detention designed to scare others. Nonetheless, we live in a world different from the one which tolerated and even fed apartheid.

Mandela’s fight promoted an agenda and international institutions where we can defend the values of freedom from encroachment by dictators and their business partners. This is why we should not consider the means of resisting oppression or seeking solidarity with other international arrangements any less conventional now. The problem is that when others see that our peaceful efforts are not fruitful, they turn to more radical means to end injustice.

*Mary Warlick is married to James Warlick, US co-chair of the OSCE Minsk Group mediating in the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. Therefore, initially I guessed that by being nice to the regime she might have tried to make her husband’s relations with the official Baku easier. But in mid-November, James Warlick announced his resignation from the post, apparently as he had planned, and my guess turned out to be mistaken.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1485781328870-cb0adaa0-0682-7″ taxonomies=”7145″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 May 2015 | About Index, Campaigns, Statements

His Excellency José Eduardo dos Santos

President of the Republic of Angola

Re: Prosecution of Rafael Marques de Morais

Dear President dos Santos,

We, the undersigned individuals and organizations, are writing to you to express our strong concerns about the prosecution on criminal defamation charges of journalist Rafael Marques de Morais. Despite what was understood to have been a negotiated agreement between Mr. Marques de Morais and government authorities late last week, we are deeply concerned that that agreement is now being reversed. Instead, it appears that the court will issue a verdict in the case later this week; a conviction could result in a prison sentence and the indefinite revocation of his passport.

This case reflects a broader deterioration in the environment for freedom of expression in Angola, including the increasing use of criminal defamation lawsuits against journalists and routine police abuse of, and interference with, journalists, activists, and protesters peacefully exercising their right to freedom of expression. We urge you to take immediate steps to reverse these worrying trends.

Mr. Marques de Morais has been regularly and repeatedly harassed by state authorities because of his work. The 24 criminal defamation charges lodged against Marques, for example, are only the latest attempt by Angolan officials to silence his reporting. Marques has alleged a range of high-level corruption cases and human rights violations in his blog, and pursued sensitive investigations into human rights violations in Angola’s diamond areas.[1] We are unaware of any serious effort by the Angolan attorney-general’s office to impartially and credibly investigate the allegations of the crimes for which he has been charged.

Your government appears to be using Angola’s criminal defamation laws to deter Mr. Marques de Morais from his human rights reporting. By doing so, the government is violating his right to freedom of expression as protected by Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Preventing him from reporting on human rights violations is contrary to the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights Defenders.

The prosecution of Mr. Marques de Morais also stands in opposition to the December 2014 judgment of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which ruled in the case of Lohé Issa Konaté v. Burkina Faso that except in very serious and exceptional circumstances, “violations of laws on freedom speech and the press cannot be sanctioned by custodial sentences.”[2] Laws criminalizing defamation, whether of public or private individuals, should never be applied, including in these circumstances given that Marques was raising concerns about human rights abuses in the country’s diamond mines. Criminal defamation laws are open to easy abuse, as the case against Marques demonstrates, resulting in disproportionately harsh consequences. As repeal of criminal defamation laws in an increasing number of countries shows, such laws are not necessary for protecting reputations.

We strongly urge you to take immediate steps to make clear that the government of Angola respects the right of journalists, activists, and others to enjoy their right to freedom of expression. Furthermore we encourage you to immediately pursue efforts to abolish Angola’s criminal defamation laws.

Thank you for your attention to this important matter.

Sincerely yours,

Sarah Margon, Washington Director, Human Rights Watch

Steven Hawkins, Executive Director, Amnesty International USA

Teresa Pina, Executive Director, Amnesty International Portugal

A. Lemon, Emeritus Fellow, Mansfield College, University of Oxford

Aline Mashiach, Head Commercial and Marketing Manager, Royalife LTD

Andreas Missbach, Joint-managing director, Berne Declaration, Switzerland

Art Kaufman, Senior Director, World Movement for Democracy

Beata Styś-Pałasz, P.E. Senior Project Manager, State of Florida Department of Transportation

Ben Knighton, Co-ordinator of the African Studies Research Group, Oxford Centre for Mission Studies (OCMS)

Carl Gershman, President, National Endowment for Democracy

Cécile Bushidi, PhD student, SOAS, University of London

Cléa Kahn-Sriber, Head of Africa Desk, Reporters Without Borders

Cobus de Swardt, Managing Director, Transparency International

Daniel Calingaert, Executive Vice President, Freedom House

Deborah Posel, Institute for Humanities in Africa (HUMA), University of Cape Town

Diana Jeater, Editor, Journal of Southern African Studies, Lecturer in African History, Goldsmiths, University of London

Dorothee Boulanger, Doctoral candidate, King’s College London

Dylan Tromp, Director, Integrate: Business & Human Rights

E.A. Brett, Professor of International Development, London School of Economics

Ery Shin, Doctoral candidate in English literature, University of Oxford

Fiona Armitage

Garth Meintjes, Executive Director, International Senior Lawyers Project

Henning Melber, Senior Advisor/Director emeritus, The Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation

Hilary Owen, Professor of Portuguese and Luso-African Studies, University of Manchester

Jaqueline Mitchell, Commissioning Editor, James Currey

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO, Index on Censorship

Kathryn Brooks, African Studies Centre, University of Oxford

Kenneth Hughes, University of Cape Town

Lara Pawson, freelance writer, Author of In the Name of the People: Angola’s Forgotten Massacre

Lotte Hughes, Senior Research Fellow, History Department, and The Ferguson Centre for African and Asian Studies Faculty of Arts, The Open University

Margot Leger, MSc Student, African Studies

Mary Lawlor, Founder and Executive Director, Front Line Defenders

Matthew de la Hey, MBA Candidate, Saïd Business School, University of Oxford

Merle Lipton, Research Fellow, King’s College London

Michael Ineichen, Program Manager & Human Rights Council Advocacy Director, International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

Michael Lipton, Research Professor of Economics, Sussex University

Michael Savage, Cape Town, South Africa

Michelle Kelly, Faculty of English, University of Oxford

Nic Cheeseman, Associate Professor in African Politics, Department of Politics and IR and the African Studies Centre, University of Oxford

Patrycja Stys, Co-Convenor, Oxford Central Africa Forum (OCAF), University of Oxford

Phil Bloomer, Executive Director, Business & Human Rights Resource Centre

Phillip Rothwell, King John II Professor of Portuguese, University of Oxford

Raymond Baker, President, Global Financial Integrity

Roger Southall, Professor Emeritus, Department of Sociology, University of the Witwatersrand

Santiago A. Canton, Executive Director of Partners for Human Rights, Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights

Simon Taylor, Director, Global Witness

Sue Valentine, Africa Program Coordinator, Committee to Protect Journalists

Suzanne Nossel, Executive Director, PEN American Center

William Beinart, Director, African Studies Centre, University of Oxford

CC:

Adão Adriano António, Attorney General of the Republic and supervisor of the central Huambo province

Lucas Miguel Janota, Magistrate of the Public Ministry

5 Feb 2015

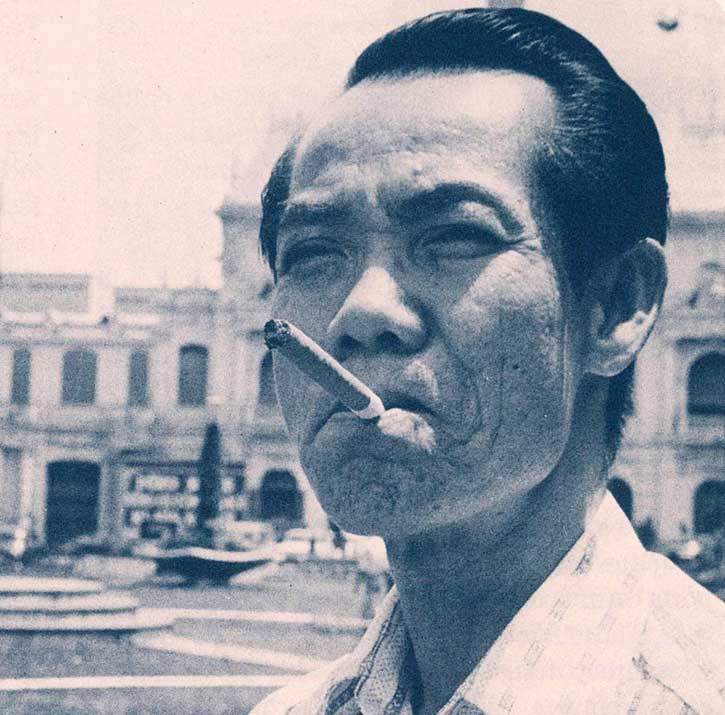

By Thomas A. Bass

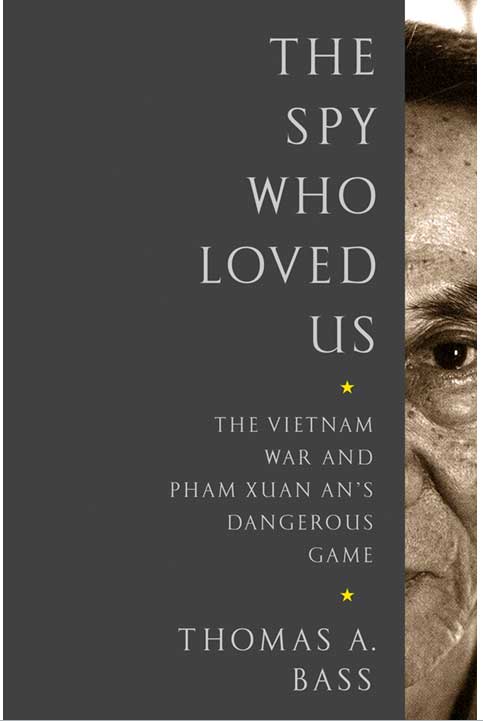

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

What the Party wants, it gets, and what it fears, it suppresses

|

About Swamp of the Assassins

Thomas Bass spent five years monitoring the publication of a Vietnamese translation of his book The Spy Who Loved Us. Swamp of the Assassins is the record of Bass’ interactions and interviews with editors, publishers, censors and silenced and exiled writers. Begun after a 2005 article in The New Yorker, Bass’ biography of Pham Xuan An provided an unflinching look at a key figure in Vietnam’s pantheon of communist heroes. Throughout the process of publication, successive editors strove to align Bass’ account of An’s life with the official narrative, requiring numerous cuts and changes to the language. Related: Vietnam’s concerted effort to keep control of its past

|

About Thomas Bass

Thomas Alden Bass is an American writer and professor in literature and history. Currently he is a professor of English at University at Albany, State University of New York.

|

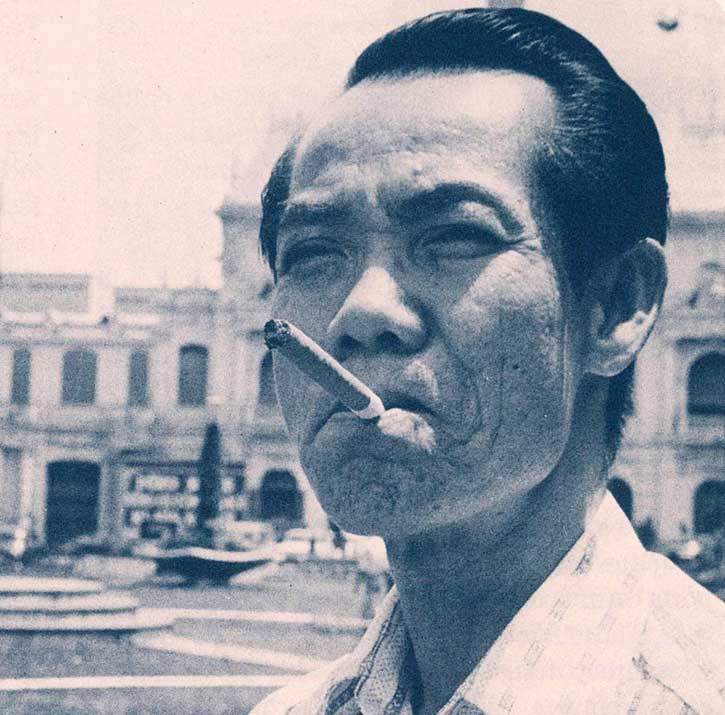

About Pham Xuan An

Pham Xuan An was a South Vietnamese journalist, whose remarkable effectiveness and long-lived career as a spy for the North Vietnamese communists—from the 1940s until his death in 2006—made him one of the greatest spies of the 20th century.

|

Contents

2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country

|

The process by which censorship works in Vietnam is described by Vietnamese reporter Pham Doan Trang in a blog post released in June 2013 by The Irrawaddy Magazine. Trang explains how, every week, the Central Propaganda Commission of the Vietnamese Communist Party in Hanoi and the Commission’s regional officials in Ho Chi Minh City and elsewhere throughout the country “convene ‘guidance meetings’ with the managing editors of the country’s important national newspapers.”

“Not incidentally, the editors are all party members. Officials of the Ministry of Information and Ministry of Public Security are also present. …At these meetings, someone from the Propaganda Commission rates each paper’s performance during the previous week—commending those who have toed the line, reprimanding and sometimes punishing those who have strayed.”

Instructions given at these meetings to the “comrade editors and publishers,” sometimes leak into the blogosphere (the online forums from which the Vietnamese increasingly get their news). Here one learns that independent candidates for political office, such as actress Hong An, are not be mentioned in the press and that dissident activist Cu Huy Ha Vu, who is charged with “propagandizing against the state,” should never be addressed as “Doctor Vu.” Also buried are reports on tourists drowning in Halong Bay, Vietnam’s decision to build nuclear power plants, and Chinese extraction of bauxite from a huge mining operation in the Annamite Range.

The weekly meetings are secret and further discussions throughout the week are conducted face-to-face or by telephone. “Because no tangible evidence remains that … the press was gagged on such and such a story, the officials of the Ministry of Information can reply with a straight face that Vietnam is being slandered by ‘hostile forces,’” Trang says. These denials were strained when a secret recording of one of these meetings was released by the BBC in 2012.

The Propaganda Department considers Vietnam’s media as the “voice of party organizations, State bodies, and social organizations.” This approach is codified in Vietnam’s Law on the Media, which requires reporters to “propagate the doctrine and policies of the Party, the laws of the State, and the national and world cultural, scientific and technical achievements” of Vietnam.

Trang concludes her report with a wry observation. “Vietnam does not figure among the deadlier countries to be a journalist,” she says. “The State doesn’t need to kill journalists to control the media, because by and large, Vietnam’s press card-carrying journalists are not allowed to do work that is worth being killed for.”

Another person knowledgeable about censorship in Vietnam is David Brown, a former U.S. foreign service officer who returned to Vietnam to work as a copy editor for the online English language edition of a Vietnamese newspaper. In an article published in Asia Times in February 2012, Brown describes how “The managing editor and publisher [of his paper] trooped off to a meeting with the Ministry of Information and the Party’s Central Propaganda and Education Committee every Tuesday where they and their peers from other papers were alerted to ‘sensitive issues.’”

Brown describes the “editorial no-go zones” that his paper was not allowed to write about. These taboo subjects include unflattering news about the Communist Party, government policy, military strategy, Chinese relations, minority rights, human rights, democracy, calls for political pluralism, allusions to revolutionary events in other Communist countries, distinctions between north and south Vietnamese, and stories about Vietnamese refugees. The one subject his paper is allowed to cover is crime, and the press is not toothless in Vietnam, Brown says. In fact, journalists can prove quite useful to the government by exposing low-level corruption and malfeasance. “To maintain their readerships, they aggressively pursue scandals, investigate ‘social evils’ and champion the downtrodden. Corruption of all kinds, at least at the local level, is also fair game.”

Another expert on censorship in Vietnam is former BBC correspondent Bill Hayton, who was expelled from Vietnam in 2007 and is still banned from the country. Writing in Forbes magazine in 2010, Hayton describes the limits to political activity in Vietnam, where Article 4 of the Constitution declares that “The Communist Party of Vietnam, the vanguard of the Vietnamese working class, the faithful representative of the rights and interests of the working class, the toiling people, and the whole nation, acting upon the Marxist-Leninist doctrine and Ho Chi Minh thought, is the force leading the State and society.” In other words, what the Party wants, it gets, and what it fears, it suppresses. “There is no legal, independent media in Vietnam,” says Hayton. “Every single publication belongs to part of the state or the Communist Party.”

Lest we think that Vietnamese culture is frozen in place, Trang, Brown, Hayton, and other observers remind us that the rules are constantly changing and being reinterpreted. “Vietnam … is one of the most dynamic and aspirational societies on the planet,” says Hayton. “This has been enabled by the strange balance between the Party’s control, and lack of control, which has manifested itself through the practice of ‘fence-breaking,’ or pha rao in Vietnamese.” So long as you “don’t confront the Party or pry too deeply into high-level corruption, editors and journalists can get along fine,” he says.

In certain circumstances, even journalists who pry more deeply can get along fine, depending on who is controlling the news leaks and for what end. This process of controlled leaks is described by another observer of censorship in Vietnam, Geoffrey Cain. In his master’s thesis, completed in 2012 at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, Cain writes that the Communist Party in Vietnam uses journalists and other writers as an “informal police force.” They help the central government keep regional officials in line, limit their bribe taking, and patrol aspects of public life that otherwise might remain in the shadows. This represents “soft authoritarianism,” which is characterized by “a series of elite actions and counter-actions marked by ‘uncertainty’ as an instrument of rule.” What is often described in Vietnam as a battle between “reformers” and “conservatives” is actually the method by which an increasingly market-oriented society can be “simultaneously repressive and responsive.” In this interpretation, journalists and bloggers lend themselves to the “informal policing” of free-market profiteers.

The “legal” mechanisms for the arrest of journalists and bloggers who overstep the boundaries, or accidentally get caught on the wrong side of shifting rules, include Article 88c of the Criminal Code, which forbids “making, storing, or circulating cultural products with contents against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam” and Article 79 of the Criminal Code, which forbids “carrying out activities aimed at overthrowing the people’s administration.” Other grounds for arrest range from “tax evasion” to “stealing state secrets and selling them abroad to foreigners.” (This was the charge leveled against novelist Duong Thu Huong when she mailed one of her book manuscripts to a publisher in California.)

Other repressive measures lie in the Press Law of 1990 (amended in 1999), which begins by declaring, “The press in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam constitutes the voice of the Party, of the State and social organizations” (Article 1). “No one shall be allowed to abuse the freedom of the press and freedom of speech in the press to violate the interests of the State, of any collective group or individual citizen” (Article 2:3). Then there is the Law on Publishing of 2004, which prohibits “propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,” the “spread of reactionary ideology,” and the “disclosure of secrets of the Party, State, military, defense, economics, or external relations.”

On goes the list of laws and regulations through various decrees and “circulars,” including Decree Number 56, on “Cultural and Information Activities,” which forbids “the denial of revolutionary achievements,” Decree Number 97, on “Management, Supply, and Use of Internet Services and Electronic Information on the Internet,” which forbids using the internet “to damage the reputations of individuals and organizations,” Circular Number 7, from the Ministry of Information, which “restricts blogs to covering personal content” and requires blogging platforms to file reports on users “every six months or upon request,” and the 2012 draft Decree on “Management, Provision, and Use of Internet Services and Information on the Network,” which requires foreign-based companies that provide information in Vietnamese “to filter and eliminate any prohibited content.”

This 2012 draft Decree was codified the following year as Decree 72, which outlaws the distribution of “general information” on blogs, limiting them to “personal information” and making it illegal for individuals to use the internet for news reporting or commenting on political events. Condemning this statute as “nonsensical and extremely dangerous,” Reporters Without Borders, in an August 2013 press release, said that Decree 72 could be implemented only with “massive and constant government surveillance of the entire internet. …This decree’s barely veiled goal is to keep the Communist Party in power at all costs by turning news and information into a state monopoly.”

Vietnam has borrowed many of these techniques for monitoring the internet from China, its neighbor to the north. According to PEN International, China has imprisoned dozens of authors, including Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo. Like China, Vietnam falls near the bottom in rankings of press freedom. Freedom House calls Vietnamese media “not free.” In 2014, Reporters Without Borders ranked Vietnam 174 out of 180 countries in press freedom. (It fell between Iran and China.) In 2013, the Committee to Protect Journalists ranked Vietnam as the world’s fifth worst jailer of reporters, with at least eighteen journalists in prison. Recently, a draconian crackdown against bloggers and anti-Chinese protestors sent dozens more to jail, for terms as long as twelve years. Pro-democracy and human rights activists, writers, bloggers, investigative journalists, land reform protestors, and whistleblowers are all being swept up in Vietnam’s totalitarian dragnet.

Part 5: Literary control mechanisms

This fourth installment of the serialisation of Swamp of the Assassins by Thomas A. Bass was posted on February 5, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Index Reports, News and features, Politics and Society

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Beyond its near neighbourhood, the EU works to promote freedom of expression in the wider world. To promote freedom of expression and other human rights, the EU has 30 ongoing human rights dialogues with supranational bodies, but also large economic powers such as China.

The EU and freedom of expression in China

The focus of the EU’s relationship with China has been primarily on economic development and trade cooperation. Within China some commentators believe that the tough public noises made by the institutions of the EU to the Chinese government raising concerns over human rights violations are a cynical ploy so that EU nations can continue to put financial interests first as they invest and develop trade with the country. It is certainly the case that the member states place different levels of importance on human rights in their bilateral relationships with China than they do in their relations with Italy, Portugal, Romania and Latvia. With China, member states are often slow to push the importance of human rights in their dialogue with the country. The institutions of the European Union, on the other hand, have formalised a human rights dialogue with China, albeit with little in the way of tangible results.

The EU has a Strategic Partnership with China. This partnership includes a political dialogue on human rights and freedom of the media on a reciprocal basis.[1] It is difficult to see how effective this dialogue is and whether in its present form it should continue. The EU-China human rights dialogue, now 14 years old, has delivered no tangible results.The EU-China Country Strategic Paper (CSP) 2007-2013 on the European Commission’s strategy, budget and priorities for spending aid in China only refers broadly to “human rights”. Neither human rights nor access to freedom of expression are EU priorities in the latest Multiannual Indicative Programme and no money is allocated to programmes to promote freedom of expression in China. The CSP also contains concerning statements such as the following:

“Despite these restrictions [to human rights], most people in China now enjoy greater freedom than at any other time in the past century, and their opportunities in society have increased in many ways.”[2]

Even though the dialogues have not been effective, the institutions of the EU have become more vocal on human rights violations in China in recent years. For instance, it included human rights defenders, including Ai Weiwei, at the EU Nobel Prize event in Beijing. The Chinese foreign ministry responded by throwing an early New Year’s banquet the same evening to reduce the number of attendees to the EU event. When Ai Weiwei was arrested in 2011, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton issued a statement in which she expressed her concerns at the deterioration of the human rights situation in China and called for the unconditional release of all political prisoners detained for exercising their right to freedom of expression.[3] The European Parliament has also recently been vocal in supporting human rights in China. In December 2012, it adopted a resolution in which MEPs denounced the repression of “the exercise of the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, press freedom and the right to join a trade union” in China. They criticised new laws that facilitate “the control and censorship of the internet by Chinese authorities”, concluding that “there is therefore no longer any real limit on censorship or persecution”. Broadly, within human rights groups there are concerns that the situation regarding human rights in China is less on the agenda at international bodies such as the Human Rights Council[4] than it should be for a country with nearly 20% of the world’s population, feeding a perception that China seems “untouchable”. In a report on China and the International Human Rights System, Chatham House quotes a senior European diplomat in Geneva, who argues “no one would dare” table a resolution on China at the HRC with another diplomat, adding the Chinese government has “managed to dissuade states from action – now people don’t even raise it”. A small number of diplomats have expressed the view that more should be done to increase the focus on China in the Council, especially given the perceived ineffectiveness of the bilateral human rights dialogues. While EU member states have shied away from direct condemnation of China, they have raised freedom of expression abuses during HRC General Debates.

The Common Foreign and Security Policy and human rights dialogues

The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) is the agreed foreign policy of the European Union. The Maastricht Treaty of 1993 allowed the EU to develop this policy, which is mandated through Article 21 of the Treaty of the European Union to protect the security of the EU, promote peace, international security and co-operation and to consolidate democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights and fundamental freedom. Unlike most EU policies, the CFSP is subject to unanimous consensus, with majority voting only applying to the implementation of policies already agreed by all member states. As member states still value their own independent foreign policies, the CFSP remains relatively weak, and so a policy that effectively and unanimously protects and promotes rights is at best still a work in progress. The policies that are agreed as part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy therefore be useful in protecting and defending human rights if implemented with support. There are two key parts of the CFSP strategy to promote freedom of expression, the External Action Service guidelines on freedom of expression and the human rights dialogues. The latter has been of variable effectiveness, and so civil society has higher hopes for the effectiveness of the former.

The External Action Service freedom of expression guidelines

As part of its 2012 Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy, the EU is working on new guidelines for online and offline freedom of expression, due by the end of 2013. These guidelines could provide the basis for more active external policies and perhaps encourage a more strategic approach to the promotion of human rights in light of the criticism made of the human rights dialogues.

The guidelines will be of particular use when the EU makes human rights impact assessments of third countries and in determining conditionality on trade and aid with non-EU states. A draft of the guidelines has been published, but as these guidelines will be a Common Foreign and Security Policy document, there will be no full and open consultation for civil society to comment on the draft. This is unfortunate and somewhat ironic given the guidelines’ focus on free expression. The Council should open this process to wider debate and discussion.

The draft guidelines place too much emphasis on the rights of the media and not enough emphasis on the role of ordinary citizens and their ability to exercise the right to free speech. It is important the guidelines deal with a number of pressing international threats to freedom of expression, including state surveillance, the impact of criminal defamation, restrictions on the registration of associations and public protest and impunity against human right defenders. Although externally facing, the freedom of expression guidelines may also be useful in indirectly establishing benchmarks for internal EU policies. It would clearly undermine the impact of the guidelines on third parties if the domestic policies of EU member states contradict the EU’s external guidelines.

Human rights dialogues

Another one of the key processes for the EU to raise concerns over states’ infringement of the right to freedom of expression as part of the CFSP are the human rights dialogues. The guidelines on the dialogues make explicit reference to the promotion of freedom of expression. The EU runs 30 human rights dialogues across the globe, with the key dialogues taking place in China (as above), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Georgia and Belarus. It also has a dialogues with the African Union, all enlargement candidate countries (Croatia, the former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia and Turkey), as well as consultations with Canada, Japan, New Zealand, the United States and Russia. The dialogue with Iran was suspended in 2006. Beyond this, there are also “local dialogues” at a lower level, with the Heads of EU missions, with Cambodia, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Israel, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, the Palestinian Authority, Sri Lanka, Tunisia and Vietnam. In November 2008, the Council decided to initiate and enhance the EU human rights dialogues with a number of Latin American countries.

It is argued that because too many of the dialogues are held behind closed doors, with little civil society participation with only low-level EU officials, it has allowed the dialogues to lose their importance as a tool. Others contend that the dialogues allow the leaders of EU member states and Commissioners to silo human rights solely into the dialogues, giving them the opportunity to engage with authoritarian regimes on trade without raising specific human rights objections.

While in China and Central Asia the EU’s human rights dialogues have had little impact, elsewhere the dialogues are more welcome. The EU and Brazil established a Strategic Partnership in 2007. Within this framework, a Joint Action Plan (JAP) covering the period 2012-2014 was endorsed by the EU and Brazil, in which they both committed to “promoting human rights and democracy and upholding international justice”. To this end, Brazil and the EU hold regular human rights consultations that assess the main challenges concerning respect for human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law; advance human rights and democracy policy priorities and identify and coordinate policy positions on relevant issues in international fora. While at present, freedom of expression has not been prioritised as a key human rights challenge in this dialogue, the dialogues are seen by both partners as of mutual benefit. It is notable that in the EU-Brazil dialogue both partners come to the dialogues with different human rights concerns, but as democracies. With criticism of the effectiveness and openness of the dialogues, the EU should look again at how the dialogues fit into the overall strategy of the Union and its member states in the promotion of human rights with third countries and assess whether the dialogues can be improved.

[1] It covers both press freedom for the Chinese media in Europe and also press freedom for European media in China.

[2] China Strategy Paper 2007-2013, Annexes, ‘the political situation’, p. 11

[3] “I urge China to release all of those who have been detained for exercising their universally recognised right to freedom of expression.”

[4] Interview with European diplomat, February 2013.