6 Apr 2023 | Events, India

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”120980″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/democracy-at-deaths-door-in-modis-india-tickets-611126414557″][vc_column_text]

As India becomes the world’s largest nation it should be the world’s largest democracy. But was India ever a real democracy? If it was, how is it being threatened under current leader Narendra Modi? And what does the word democracy even mean?

In its 76th year since independence India will go to the polls next year. Modi is hugely popular and is tipped to win. But under his leadership the press, once vibrant, is being strangled, the judiciary is no longer independent, laws have been amended to throw protestors in jail, opposition figures are harassed, and minorities live in fear. While the global attention is focused elsewhere, Indians are fighting to protect their human and civil rights.

What can be done to protect the rights of minorities in India? What will Modi’s priorities be ahead of the 2024 elections? And crucially just how resilient is Indian democracy and is it open to everyone? The newest edition of Index on Censorship magazine explores these questions as we examine the role of free expression in contemporary Indian society. To launch the issue join us for an animated online panel discussion about past, present and future challenges to India’s democracy.

Meet the speakers

Salil Tripathi is an award-winning journalist born in Bombay and living in New York. He has written three works of non-fiction – Offence: The Hindu Case, about Hindu nationalist attacks on free expression, The Colonel Who Would Not Repent, about the war of independence in Bangladesh, and a collection of travel essays. He is writing a book on Gujaratis. More recently, he co-edited (with the artist Shilpa Gupta) an anthology honouring imprisoned poets over the centuries. He has been a correspondent in India and Southeast Asia. He was chair of the Writers in Prison Committee at PEN International and is now a member of its international board. He has studied in India and the United States and lived in the UK.

Dr Maya Tudor is an Associate Professor of Politics and Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford. She researches the origins of effective and democratic states with a regional focus on South Asia. She is the author of two books, The Promise of Power: The Origins of Democracy in India and Autocracy in Pakistan (2013) and Varieties of Nationalism (with Harris Mylonas, 2023 Forthcoming). She writes for the media on a regular basis, including in Foreign Affairs, Washington Post, New Statesman, The Hindu, India Express, and The Scotsman.

Hanan Zaffar is a journalist and film maker based in South Asia. He reports on Indian minorities and politics. His work has appeared in Time Magazine, VICE, Al Jazeera, DW News, Newsweek, TRT World, Channel 4, Middle East Eye, The Diplomat, and other notable media outlets.

Jemimah Steinfeld is editor-in-chief at Index on Censorship. She has lived and worked in both Shanghai and Beijing where she has written on a wide range of topics, with a particular focus on youth culture, gender and censorship.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Wednesday 3 May 2023, 2.00-3.00pm BST

Where: Online

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Feb 2021 | India, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Farmers protesting/Randeep Maddoke/WikiCommons

India is currently witnessing one of its longest and largest ever expressions of dissent. Farmers – protesting three laws passed in September by the central government – have been camping at the borders of the national capital since 26 November last year, challenging the powers in New Delhi.

The protests would seem, on the surface, to show that India is functioning as a democracy with the freedom of individuals to protest. It is therefore ironic that at least seven journalists have been booked for reporting on the events that have transpired during the clashes between police and authorities.

On 29 January , six prominent journalists – Rajdeep Sardesai, Mrinal Pande, Zafar Agha, Vinod Jose, Paresh Nath and Anant Nath – were booked by Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh police under charges of sedition, criminal conspiracy and promoting enmity.

A day later, freelance journalist Mandeep Punia, who was on a project for The Caravan magazine, was detained by the Delhi police, a few hours after he went live on Facebook and reported on how stones were pelted at the farmers at Singhu border, even as security personnel looked on. He has since been granted bail.

Based on eyewitness testimony during a rally by the protesting farmers on Republic Day, 26 January, when India celebrates the 1950 entry into force of its Constitution, The Caravan reported that a man was killed after being shot by the Delhi police. Sardesai, Pande and Agha’s tweets echoed the testimony.

Police have vehemently denied shooting the farmer, which they claim is backed up by an autopsy report. However, the man’s family has refused to accept the Delhi police’s claim. “The doctor even told me that even though he had seen the bullet injury, he can do nothing as his hands are tied,” the farmer’s grandfather told Indian news website The Wire.

Siddharth Varadarajan, founding editor of The Wire, was booked by the Uttar Pradesh police for tweeting the police report of the incident.

While the controversy around the farmer’s death is far from settled, the government’s decision to go after these journalists is only the latest episode of its effort to gag the voices that have dared to question it.

The question arises, why would the central government of the largest democracy in the world choose to take these steps? This was answered by the secretary general of the Press Club of India during a meeting organised to protest the intimidation of journalists covering the protests.

“The government is sending a message that while on paper we’re a democracy, we are behaving like several undemocratic states of the world,” Anand Kumar Sahay said.

The statement encompasses almost everything that journalists in India, who are not toeing the line yet, deal with as they try to speak truth to powerful authorities. India lies 142nd on Reporters Without Borders’ world press freedom rankings.

RSF says: “Ever since the general elections in the spring of 2019, won overwhelmingly by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, pressure on the media to toe the Hindu nationalist government’s line has increased.”

That a large number of journalists are being booked, arrested or assaulted for doing their job just around these farmers’ protest tells a worrying story. A more thorough examination of the cases, with focus on the organisations that these journalists represent and the ideology that they support, will show whether Modi is targeting just the critical media or journalism as a whole.

There are also more covert ways in which the far-right party that governs the Indian state has told news establishments to not speak out against them if they want to preserve their business.

The mainstream news organisations in the country typically function on an advertisement-based revenue model. While this has helped in keeping the cost of the national dailies low, it has also made them dependent on large corporations and the government, the two biggest advertisers in newspapers.

As expected, the government has not missed the opportunity to milk this dependency and has led many media organisations to indulge in self-censorship and push the government agenda forward, particularly during the Covid pandemic when government advertising has increased.

While there is ample evidence of censorship by the Indian government on independent news websites like Newslaundry, it was also hinted at by the Modi in an interview with prominent English daily The Indian Express, in the run-up to Assembly Elections 2019.

In the article, Modi talks about the PM-KISAN income support or ‘dole’ scheme for farmers and compares this with payments received by other sectors from the government, such as publishing.

“I give advertisements to the Indian Express. It doesn’t benefit me, but is it a dole? Advertisements to newspapers may fit into a description of dole,” Modi said.

Media organisations are therefore on a warning by the government.

The close government scrutiny had also become clear back in 2018, when anchor Punya Prasun Bajpai was forced out from ABP News.

In a detailed account of the reasons behind his departure, Bajpai described how the channel’s proprietor had told him to avoid mentioning Modi’s name in the context of any criticism of the government.

Bajpai also described a 200-member monitoring team that was involved in observing news channels resulting in directives that would be sent to editors about what should be showed and how.

These “commandments”, which were reserved for TV news and large national dailies until 2019, have now reached the digital versions of these conventional news organisations. The only journalistic outfits who have dared to critically examine this government’s rule operate as digital platforms. The government is thus looking to “regulate” their work as well.

Censorship of content that is consumed by millions has not existed before on this scale.

But it has now permeated the Indian media to such an extent that freshers starting work in media are being told to “ride the tide” and “reserve their optimism” for when the political environment is less volatile.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”5656″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 May 2020 | India, News and features

Image by Raam Gottimukkala from Pixabay

A friend in the police department apologetically texted me with some “friendly” advice. “Don’t be extra active on social media over corona issues which may lead to panic and rumours. There may be legal issues over it,” he said.

He wouldn’t elaborate further, but it didn’t take much to understand. A freelance journalist was arrested in Andaman and Nicobar Islands for a tweet on a bizarre quarantine rule. At least 13 people from various walks of life have been arrested since 1 April in Manipur for Facebook posts. A doctor at a government hospital had been harassed by the police and questioned for 16 hours at a police station after he put up a Facebook post complaining about the lack of protection gear for doctors. A founder of an online publication was arrested in Tamil Nadu for reports on problems faced by government healthcare workers. In Chhattisgarh, a journalist was slapped with a notice threatening arrest for his report on the plight of women in lockdown.

The pandemic has given the government free rein. India is witnessing very high levels of suppression of free speech and media censorship across the country.

“Everything is censored,” said a Kolkata-based journalist, declining to be identified. “You cannot report on anything that is not confirmed by the government. Getting data on anything is an ordeal.”

In the name of curtailing rumours and fake news, there have been curbs on free speech and freedom of journalists to cover the pandemic, especially those with questions that make the government uncomfortable. “It’s as if the media is an opponent. It is as if asking questions of the government is a crime, or a politically motivated exercise,” said the journalist.

On 30 March, Scroll.in published a list of ten questions that health beat reporters in Delhi had for the central government but did not get any answers. These included: How did the Indian government arrive at the pricing of the Covid test in private labs, which is Rs 4,500 ($60), and among the highest in the world? Why has the drug controller not released the list of Covid-19 testing kits that have been granted import and manufacturing licences? What are the steps the government is taking to map the scale of Covid-19 outbreak in the community? What arrangements have been made to ensure patients living with life-threatening conditions like cancer, tuberculosis and HIV that require continuous support are not deprived of critical care?

While questions such as these remain unanswered, journalists covering the Covid crisis say they are witnessing unprecedented levels of censorship. Government interaction with the press is stressed. Prime Minister Modi, in keeping with his record, has not organised a single press conference on the issue. Harsha Vardhan, a health minister, has interacted infrequently with the press, while the daily press briefings are conducted by a senior bureaucrat in the health department, Lav Agarwal.

“In the ministry’s organisation structure,” writes Vidya Krishnan in Caravan magazine, “Agarwal comes after two secretaries, four special secretaries and four additional secretaries, and is one of the thirteen joint secretaries in the ministry of health.”

Even the press briefings are not for all journalists. Barring Doordarshan (DD), India’s public broadcaster, and news agency Asian News International and a few accredited journalists, others have been barred from attending the press briefings in the name of social distancing. “The directive on social distancing became an excuse to not have journalists in the room,” said Anoo Bhuyan, Delhi-based health reporter with Indiaspend, a data journalism-based news portal.

“Then we got a message one day saying other than ANI and DD no one needs to attend the press conference. They said we could send our questions through WhatsApp. However, there is no guarantee that your question will be picked to be answered by Mr Agarwal. It is like a lucky draw without any rationale and definitely does not give equal chances to all journalists. In the very short time allotted for questions, only two to four questions are picked up, some of which are repetitions.”

The Modi-led government even approached India’s Supreme Court to legalise censorship by seeking an order that would prevent the media to publish anything “without ascertaining the true factual position” from the government. The court did not go that far, only directing the media to “refer to and publish the official version about developments”.

“The order itself does not have teeth, but the fact that there is an order may freak out many,” said Bhuyan. “It gets diabolical in that Lav Agarwal makes it a point to sometimes refer to the order and ‘remind’ journalists to ‘exercise caution’ and ‘report responsibly’.”

“What’s happening in India is extremely disturbing,” Vidya Krishnan, a Goa-based health reporter with Caravan magazine, tweeted on April 1. There is a media gag in place, doctors have been threatened to not speak out against lack of PPE kits, and the health ministry says we have no local transmission (without scaling up testing). Genuinely struggling to understand how we can continue reporting in this Orwellian setting.”

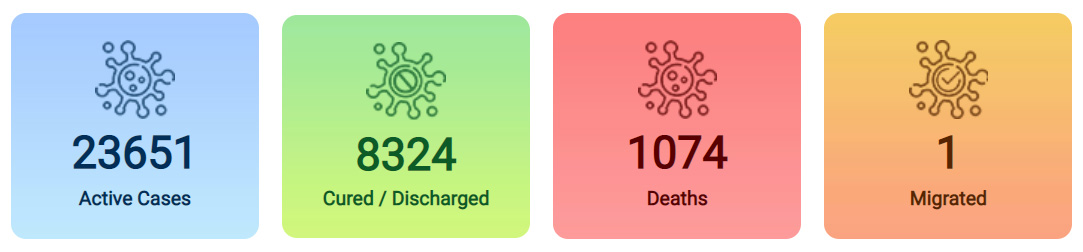

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, data correct as at 30/4/2020

Meanwhile, Mamata Banerjee, chief minister of the Indian state of West Bengal, announced insurance cover for journalists covering Covid from the frontlines. It is a combination of medical and life cover worth 10 hundred thousand Indian rupees (£10,500). There’s one rider: journalists have to do “positive” stories. “People are depressed seeing negative news all the time,” she said. “Journalists should be involved with the government,” she added without leaving anything to doubt.

This came just two days after she threatened legal action against journalists if they report “unconfirmed” fatality figures. Banerjee, who has a record of booking journalists, academics and the general public for social media posts critical of her, faces allegations that she is supressing Covid-related data in the state. The state has a special committee to “audit” and “ascertain” Covid deaths.

Banerjee has asked journalists to “behave properly” or face legal action.