1 Dec 2015 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Poland

Fact-checking is crucial for any piece of journalism. This was what the investigative journalist Jaroslaw Jakimczyk set out to do when he wrote an email to the press office at IT and technology company Qumak S.A. requesting authentication of information he had.

The company, which is based in Warsaw, provides information and communication services to well-known clients, such as the major Polish bank Pekao. Jakimczyk’s questions pertained to discs of private client data that, according to his information, there was proof of a transaction of sale between the two parties. When Jakimczyk received a response from Qumak’s press office in late September, the denial of any wrongdoing on their part was followed swiftly by something rather unexpected: Qumak was now pressing charges against Jakimczyk for defamation under article 212 of the Polish penal code.

Under article 212 of the Polish penal code, defamation is when one person defames another individual, group, company or association, over such characteristics “that might lower it in the public opinion or contribute to the loss of trust which is required for the office executed by it”. Defamation can be subject to up to a year’s imprisonment if “done through means of mass communication” under paragraph 2; without mass communication, one might just get away with a fine or, rather vaguely “limitations to freedom”. Until amendments were made to the law in 2010, imprisonment was a general possibility. A public apology is usually also a popular demand with any article 212 claim.

Defamation charges appear to have been keeping Polish judges increasingly busy over the years: The Helsinki Foundation of Human Rights, in its publication on article 212, points out that while 43 article 212 claims were put forward in 2000, by 2011, this figure had risen to 232. At times, the entire Polish judicial system is exhausted. This happened to Andrzej Marek in 2004, who had accused a local politician of corruption in an article, and Marian Maciejewski, who had written articles critical of judicial inaccuracies in the city of Wroclaw.

In both instances, defamation charges were pressed, and both cases took years to reach the European Court of Human Rights to be ruled breaches of article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which deals with free expression. The court ordered compensation payments for the journalists. Five more very similar cases were rejected by European Convention in the same way. But article 212 claims continue to dog journalists.

A part in the explanation for the increase of claims lies, for multiple reasons, with the internet. As Dorota Glowacka, an expert on 212 at the Helsinki Human Rights Foundation, told Index on Censorship, the fact that information is online might instill a heightened sense of urgency in potential claimants, as “the statements would be perceived as more harmful to their reputation, due to them remaining ‘online forever’”. Paradoxically, the accessibility of information through the web, according to Jakimczyk, might also work against them: “Many representatives of local oligarchies who read and analyse online publications on the subject have come to the somewhat correct conclusion that there are means to silence uncomfortable journalists.”

A review of cases of journalists charged with article 212 shows that local authorities are often involved. Earlier this month, the mayor of the small municipality in south-east Poland, Blachownia, decided to press charges against the editor-in-chief of a critical independent local news portal. As Jakimczyk noted, “previously, many of those based in Polish provinces had not heard of such a possibility or did not have enough courage to go ahead with them”, but the “amplification of cases charged with article 212 might have encouraged them to take up the same”.

In fact, council authorities sometimes press charges under 212 on behalf of a criticised local politician, arguing that such criticism “hits the good reputation of the whole council”, as Glowacka said. Such cases are rather comfortable arrangements for the politicians, as it involves no expenditures or extra efforts of their own: they can make use of the council’s legal services, and any costs relating to the case will be paid for.

Glowacka said that the cases reaching the attention of the Helsinki Human Rights Foundation have still largely been those of journalists and political activists. Increasingly, though, even the average citizen leaving a negative product or brand review, might get sued for defamation. And if comments are left anonymously, then article 212, as part of the criminal code, guarantees police support in subject identification; if one were to consider taking up the alternative route through the civilian code that also protects personal goods and good reputation, this possibility does not exist.

Attempts to strike the article from the criminal code have come from many angles over the years: between 2007 and 2012, the OSCE, the Council of Europe, as well as freedom of speech and human rights delegates of the UN openly criticised the article for curtailing freedom of speech. The diplomat Irina Lipowicz had challenged the possibility of imprisonment for defamation before the Polish Constitutional court three years ago, but that only pointed to its 2006-ruling, when it was decided article 212 did not infringe upon freedom of speech.

In 2011, the Polish citizen Mariusz S. filed a petition to remove 212 from the Polish criminal code, but the voting did not bring about a clear majority and the provision remained in place. The Helsinki Human Rights Foundation, in the run-up to the 2011 national parliamentary elections, promoted a large-scale campaign to ‘Erase article 212’. At the time, 140 Polish MPs declared they would support a move to drop the defamation clause.

It appears, though, that there is a lack of substantial, genuine political will, and that, too often, it presents itself as a handy “whip” or looming “sword of Damocles”, Glowacka and Jakimczyk said. The former points to an illustrative example of the Polish People’s Party [org.: Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe], which officially backed the Erase initiative in 2011, only for its vice chair Eugeniusz Grzeszczak to put forward claims against journalists in his constituency a year later, when he disagreed with their revealing his payments to a favourable publisher. For Polish politicians to truly find interest in removing the provision, “an incident would be needed of accusations on article 212 pressed against a representative of this very class, which appears to consider itself as a club of untouchables”, Jakimczyck commented.

The journalist underscored another, deeper issue that the threat of defamation charges makes possible. The ties between business and media publishers are close to the extent that they lead to “the introduction of unwritten rules, limiting or excluding publication of critical material on certain companies, corporations or public institutions, which have a large advertising budget to their disposal.” It does not seem a coincidence that critical material has been increasingly held back, especially since the financial crisis in 2008, he said.

In Jakimczyck’s experience, this has pertained to any reports on firms which the state treasury has shares in, including major names such as the largest Polish insurance firm PZU, the copper and silver production company KGHM Polska Miedz, the Polish oil refiner and retailer Orlen, as well as the Polish Energy Group. Every time an article remained unpublished, “never did those responsible [at the paper in question] provide a satisfactory justification as to why publication was denied”. The incident with Qumak’s charges, tied budget-wise to the largest Polish bank, is no longer an isolated incident so much as “the further logical consequence of the new phenomenon that is preventive censorship”. Worryingly, these are not publicly accountable institutions but rather in the hand of “private capital that is not subject to societal checks and balances”.

Jakimczyk’s case, in the meantime, appears resolved: in a court ruling earlier this month, judges found that to qualify for defamation, the content in question has to have at least been shared with one other person; judges have also raised the crucial point that a journalist’s main role is to ask questions, i.e.: the journalist was just doing his job. Qumak S.A. will now have to cover any resulting fees for courts.

Although the company is legally entitled to claim revision, for the sake of the state of journalism in Poland, it is hoped that this case will remain at that, and set an ultimate example what worrying direction alleged defamation charges should stop going to in Poland.

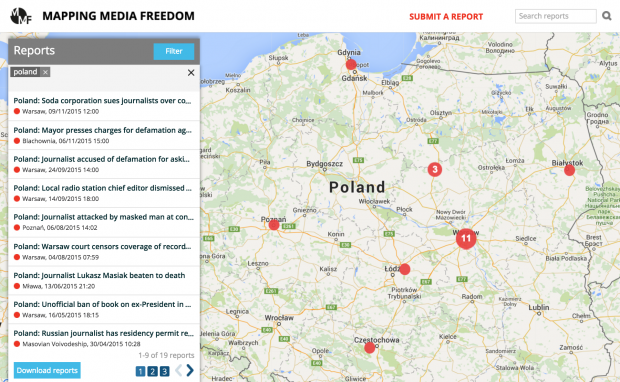

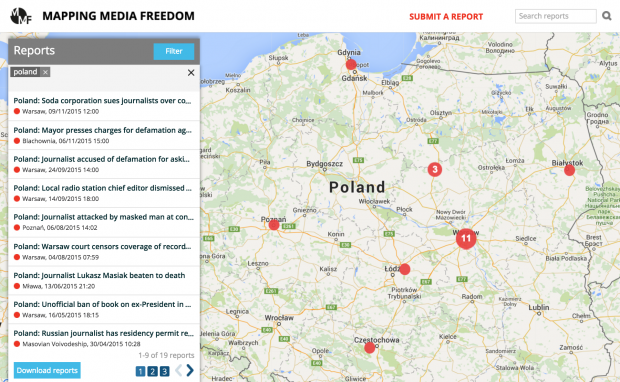

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

24 Jun 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Poland

Journalist Lukasz Masiak, founder of news site NaszaMlawa.pl, was attacked and killed in Poland on 14 June 2015. Masiak, who had been subject to numerous threats believed to be connected to his work, died of traumatic brain injury after being assaulted, according to TVN24.

Launched in 2010, NaszaMlawa.pl covers Mlawa, a town of about 30,000 in the north central part of Poland. Masiak’s site reported on several controversial issues, including the dealings of local businessmen, drug use involving participants of the local mixed martial arts league, incidents involving Roma citizens in the area and the botched investigation into the death of a young woman. He received death threats following the latter story.

The attack on 31-year-old Masiak took place in the bathroom of a local establishment at about 2am on 14 June. Police have issued an international arrest warrant for Bartosz Nowicki, a 29-year-old mixed martial arts fighter. Two people who were earlier detained have now been released. Police consider them witnesses to the incident.

Masiak had previously received threats over the phone and through the mail, local media reported. In December 2014, he was sent his own obituary. In January 2014, he was the victim of a physical assault in near his home, in which he said he had also been tear gassed.

“It certainly was not a robbery.” Masiak said at the time. “It was a person who was waiting for me. For sure it was about posting reports on the portal.”

Though the journalist had reported incidents to the police, there had been no arrests by the time of his murder.

Alicja Śledziona, police spokesperson for the region of Mazowieckie, said that the department had received two complaints from the journalist. Masiak had told the department that the January and December 2014 incidents could have been related to his reporting, including one about a traffic accident. She said both cases were treated very seriously, but investigators were unable to tie the incidents to individuals.

The killing has been met with widespread condemnation from press unions and media freedom organisations.

“Media workers in Europe are facing an increased level of violence as they do their jobs. We call on the European Union and governments across the continent to mount a concerted effort to protect press freedom and the lives of media workers by aggressively pursuing threats of violence against journalists,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

“Index has been tracking threats to journalists across Europe for more than a year, through our Mapping Media Freedom project, and have noted a worrying trend of violence towards the sector. Around the world, there have been 54 murders of journalists so far this year. It shouldn’t have to take another death to make protecting journalists a priority at the highest levels of government,” Ginsberg added.

The crime was condemned by the Press Freedom Monitoring Centre of the Association of Polish Journalists. The body wrote to Polish Interior Minister Teresy Piotrowskiej, criticising the failure of state authorities to provide him with “elementary security”.

Mogens Blicher Bjerregård, president of the European Federation of Journalists, shared his organisation’s condolences with Masiak’s family and demanded an “effective investigation in order to find and prosecute the responsible perpetrators for this horrible crime”. EFJ, along with Reporters Without Borders, is partnered with Index on the Mapping Media Freedom project.

Dunja Mijatović, the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, strongly condemned the killing and expressed her condolences to Masiak’s family and colleagues. “This is a tragedy and a horrific reminder of the dangers journalists face around the world,” Mijatović said. “Journalists are increasingly targeted because of their profession and what they say and write, and this trend has to stop.”

18 Aug 2014 | News and features, Poland, Religion and Culture

Ewa Wojciak has been working in the in theatre since the 1970s when she was a dissident artist under the communist regime. (Photo: Maciej Zakrzewski)

Ewa Wojciak, director of Poland’s Theatre of the Eighth Day, was fired by Poznan mayor Ryszard Grobelny on 28 July. His administration oversees culture and arts in the city, including Wojciak’s subversive and anti-establishment theatre group.

The official reason given was that she did not ask for permission to leave the city between 18 and 28 February, when she visited Yale and Princeton universities, performing her touring duties as director and actress with the theatre. However, these trips were not sponsored by the local government, so it is hard to see why she would need permission from authorities.

Wojciak’s career with the theatre began in 1970 when she was a dissident artist under the communist regime. After the end of communism, she turned the theatre into a welcoming space for refugees, minorities, anti-facists, feminists, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people and emerging theatre-makers. She has become a “new dissident”, confronting the realities of life after communism. During her tenure, the theatre, known for its artistic experimentation and politically subversive productions, has drawn the fire of Grobelny, known for his ultraconservative views.

The Theatre of the Eighth Day has played at the Edinburgh Festival, London’s LIFT, at the universities of Yale and Princeton, as well as innumerable major and small venues in Poland. The New York Times has written on their production under the heading “When Courageous Artists Ripped Holes in the Iron Curtain“.

During last month’s Index on Censorship debate with Timothy Garton Ash, Kate Maltby and David Edgar, about freedom 25 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I tried to emphasise how important such new dissidents are in Eastern Europe. Commenting on this debate, Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg reminded us how authorities are taking an increasingly hard line on civil society groups.

The Theatre of the Eighth Day, which helped build an alternative civil society under communism, continues its non-conformity — and faces threats from Poznan’s political establishment. Wojciak is being unfairly dismissed for defying the far right, clericalism, the “moral majority” and censorship.

Grobelny’s record as mayor of Poznan, a job he has held since 1998, leaves much to be desired in an open, democratic society. He has repeatedly stifled independent voices in the city, and Wojciak has been a long-standing adversary. In 2005, Grobelny banned the Equality March, a feminist-queer pride event. Wojciak and other members of the Theatre of the Eighth Day took part in this forbidden event, which was suppressed by the police — one of the actors was arrested. More recently, Grobelny also supported the Poznan ban of the play Golgota Picnic, on which Index has reported.

In 2013 Wojciak was reprimanded by the mayor for a comment on her Facebook wall immediately after the conclave of Pope Francis: “[T]hey’ve elected a prick who denounced left-wing priests under the military dictatorship in Argentina.” Her Facebook account was shut down and Wojciak — mistaken about the Pope’s involvement with the Argentinian junta — was vilified by Poland’s far right. Her Facebook account was later restored and the Poznan prosecutor declined to pursue the matter. At the time, intellectuals and artists defended her on grounds of free expression.

Adam Michnik, editor-in-chief of Poland’s leading broadsheet Gazeta Wyborcza and a legendary dissident, wrote that he supports Wojciak. Michnik is a member of the committee of the fiftieth anniversary of the Theatre of the Eighth Day. A petition protesting the dismissal of Wojciak has been issued by civic-educational initiative Otwarta Akademia (“Open Academy”), spearheaded by Piotr Piotrowski, an art historian and former director of Warsaw’s National Museum (who initiated the groundbreaking exhibition Ars Homo Erotica there), feminist Izabela Kowalczyk, artist Marek Wasilewski and ethicist Roman Kubicki, among others.

This petition has so far been signed by 317 people, including Irena Grudzinska-Gross of Princeton University and Alina Cala of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, who both write on anti-semitism in Poland; Elzbieta Matynia of the New School for Social Research and author of Performative Democracy; Jeffrey C. Goldfarb, author of The Persistence of Freedom: The Sociological Implications of Polish Student Theatre; and Pawel Leszkowicz of Poznan University, curator of Ars Homo Erotica.

The Theatre of the Eighth Day epitomises liberty: Wojciak and her company speak out against injustices and experiment aesthetically. It’s deplorable that they should be repressed by the authorities of their city.

If you would like to protest the dismissal of Ewa Wojciak, please email [email protected] with the subject “Ewa”.

This article was posted on August 18, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Jul 2014 | News and features, Poland, Religion and Culture

Golgota Picnic was pulled from a the Malta Festival in Poland after religious groups leveled threats.

The Polish theatre scene has been rocked by controversy since late June after the cancellation of Golgota Picnic, a show by the Argentinian theatre maker Rodrigo Garcìa that had previously aroused protest in France.

The play’s supposedly blasphemous content meant that Michał Merczyński, director of the Malta Festival, had pulled the headline show of his festival a week before its scheduled performance. The Malta Festival in Poznań is Poland’s answer to the Edinburgh Festival, and I was visiting with other directors from the Young Vic to learn more about Polish theatre culture. Our experience of the festival was derailed by claims and counter claims of blasphemy and censorship.

Merczyński’s decision to pull the show was based on information that a protest of 50,000 was planned and advice from the police that they could not guarantee the safety of the audience or the performers. The festival’s decision enraged large parts of secular Poland’s cultural elite, who feared that the police warning represented the state’s acquiescence to unofficial censorship by a group of interests centred upon the increasingly powerful Catholic church.

In reaction to the cancellation, there was a proliferation of protest screenings and staged readings of Golgota Picnic in theatres across Poland, some of which were variously picketed by a loose coalition of Catholics, neo-nazis and football hooligans. At the protest screening my group attended, at TR Warzsawa in Warsaw, these three groups all appeared to be embarrassed by each other. They prayed together and held placards warning that “Poland, motherland of Saint John-Paul II must not be a latrine for the trashes of the blasphemer, of the scoffers, of the traitors, of the barbarian and pseudo-artists”.

The Young Vic directors were jostled as we attempted to get in to the theatre and through the double cordon — first the protesters trying to stop us getting into the theatre, and then the police holding back the protesters. In the end we climbed over a low fence around a corner to get in and the police quickly bundled us into the building.

It’s important to say that this was much more exciting than it was scary. Here was evidence that theatre matters: people threatening hostility, if not quite violence, in response to an artwork. As far as I could make out from the DVD, Golgota Picnic (screened in Spanish with Polish subtitles) was a considered and beautiful meditation on the body and on Christ’s body in particular. Although it included a scene where a woman playing Jesus sculpted her gelled hair over another person’s genitalia, I’ve certainly seen more blasphemous plays. The crowd outside were fairly audible in their hymns and their chants, but — in the end, the protesters were defeated by the length of a piece of theatre. When we emerged two and a half hours later, they had given up and gone home.

The cancellation of Golgota Picnic left the Malta Festival deflated, but it felt as if these protests might be a powerful shot in the arm for Polish theatre culture in general. Several people we met were excited by the possibilities of the networks created and issues raised in the fight against religious censorship. Polish theatre provided a central political role in the end years of communism, and then lost its way only to be reinvented at the end of the nineties as a means to interrogate more universal themes in the formally explosive theatre of Gzegorz Jarzyna, Krzystof Warlikowski and Jan Klata, directors who still dominate the scene. It appears that Polish theatre is ripe for a new generation to redefine what theatre means.

As an outsider, this culture war looked complex and unhappy. Of course I was inside the theatre rather than on the street with a rosary, but it was clear that all the theatre people we met were well educated and well heeled. The Catholic protesters were not, and they felt like a demographic who had been left behind by the neo-liberalism that has replaced communism. It’s hardly surprising that these people are angry to see that “they are mocking us”, as one man complained to us on the steps of TR Warszawa.

It’s worrying to encounter theatre censorship in the EU, and artists should be free to present their work. At the same time, theatre institutions have a responsibility to ensure each piece of work finds its audience in the most productive way possible. With Golgota Picnic, the Malta Festival imported a show that had already caused protests elsewhere. Their marketing presented it as sexily controversial, and when this spectacularly backfired they cancelled the performance. Artists should shock and offend, but theatre makers and producers have to tread thoughtfully to ensure that the presentation of powerful work doesn’t play into the hands of those who would censor it.

Jeff James’s visit to Poland was supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute, the Young Vic and the Jerwood Charitable Foundation.

This article was posted on July 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org