Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

The autumn issue of Index takes as its central theme the FIFA World Cup that will take place in Qatar in November and December 2022.

A country where human rights are constantly under threat, Qatar is under the spotlight and many are calling for a boycott of the tournament.

Index spoke to journalists, human rights activists and philosophers for the latest issue to understand their view on the tangled relationship between football and human rights. Is football really the beautiful game?

The Qatar conundrum, by Jemimah Steinfeld: The World Cup is throwing up questions.

Chasing after rights, by Ben Rogers: The activist on being followed by Chinese police.

Victim of its own success? By Simon Barnes: Blame the populists, not the game.

The stench of white elephants, by Jamil Chade: Brazil’s World Cup swung open Pandora’s Box.

The real game is politics, by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Is politics welcome on the pitch in Kenya?

Much ado about critics, by Lyn Gardner: A theatre objects to an offensive Legally Blonde review.

On reputation laundering, by Ruth Smeeth: Beware those who want to control their own narrative.

LGBTQI rights. Gender equality. Media freedom. The fate of liberties in Hungary hang in the balance as the nation heads to the polls on Sunday. With a falling currency, a mismanaged response to the pandemic still fresh to mind and a stronger opposition under United For Hungary – a coalition of six parties spanning the political spectrum – the election campaign has been the closest in years. But the war in Ukraine, right on Hungary’s border, has changed its course in unexpected ways. Below we’ve picked the most important things to consider when it comes to the April 2022 elections.

Basic rights could worsen

Since his election in 2010, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has whittled away fundamental rights in the country to the extent that Hungarian activist Dora Papp told Index in 2019 free expression had no more space “to worsen”.

Orban’s main targets have been people who identify as LGBTQI. Last year, amid global outcry, he passed a law that bans the dissemination of content in schools deemed to promote homosexuality and gender change. Seeking approval for this legislation, Hungary is holding a referendum on sexual orientation workshops in schools this Sunday alongside the parliamentary elections.

Orban also takes aim at the nation’s Roma and immigrants, and has revived old anti-Semitic tropes in his attacks on George Soros, a Hungarian-born Jewish philanthropist who Orban claims is plotting to flood the country with migrants (an accusation Soros firmly denies).

As for half of the population, Orban’s macho-style leadership manifests in rhetoric on women that is dismissive, insulting and focuses on traditional roles. Asked in 2015 why there were no women in his cabinet, he replied that few women could deal with the stress of politics. That’s just one example. The list goes on.

His populist politics have seeped into every democratic institution and effectively dismantled them. The constitution, the judiciary and municipal councils have all been reorganised to serve the interests of Orban. Education, both higher and lower, has seen huge levels of interference. Progressive teachers and classes have been removed. Even the Billy Elliot musical was cancelled after Orban called the show a propaganda tool for homosexuality.

But the media can’t freely report much of this

In response to claims of media-freedom erosion, the Hungarian government likes to point out that there are no journalists in jail in Hungary, nor have any been murdered on Orban’s watch. But as we know only too well there are many ways to cook an egg. Through gaining control of public media, concentrating private media in the hands of Orban allies and creating a hostile environment for the remaining independent media (think misinformation laws and constant insults), the attacks come from every other angle. Orban has even been accused of using Pegasus, the invasive spyware behind the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Kashoggi, to target investigative journalists.

It’s little wonder then that in 2021 Reporters Without Borders labelled Orban a “press freedom predator”, the only one to make the list from the EU.

As election day approaches the attacks continue. In February, for example, pro-government daily Magyar Nemzet said it had obtained recordings showing that NGOs linked to Soros were “manipulating” international press coverage of Hungary, a claim instantly rejected by civil society groups.

Ukraine War has shifted the narrative, for better and worse

Given Orban’s track-record on rights, it comes as no surprise that he’s the closest EU ally of Vladimir Putin. This wasn’t a great look before 24 February and it’s even less so today, as the opposition are keen to highlight. They are pushing Orban hard on his neutral stance, which has seen him simultaneously open Hungary’s borders to Ukrainian refugees and oppose sanctions and the sending of weapons.

But Orban is playing his hand well. Fears of becoming embroiled in the war appear to be stronger in Hungary than anger at Putin’s aggression, many analysts says. Orban is claiming a vote for him is a vote for stability and neutrality, while a vote for the opposition is a vote for war. He’s even tried to cast his February visit to Moscow as a “peace mission”.

And though he has condemned the invasion, he has yet to say anything bad about Putin himself. Worse still, Hungarian media is blasting out Russian propaganda. Pundits, TV stations and print outlets are pushing out lines like the war was caused by NATO’s aggressive acts toward Russia, Russian troops have occupied Ukraine’s nuclear plants to protect them and the Ukrainian government is full of Nazis.

Anything else?

Yes. Orban met with a coalition of Europe’s far-right in Spain at the start of the year. They discussed the possibility of a Europe-wide alliance. What that looks like now in a post-Ukraine world is hard to tell. We’d rather not see.

Then there’s the fact that Serbia also goes to the polls Sunday. Like Orban, the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), led by president Aleksandar Vučić, has been unnerved by growing opposition. Also like Orban, they’re close to Putin and using the Ukraine war to their advantage – reminding people of the 1999 Kosovo war when NATO launched a three-month air strike. Orban and Vučić have developed close ties and will no doubt be buoyed up by each other’s victories should that happen on Sunday.

So will the Hungary elections be free and fair?

If the 2018 elections are anything to go by, they will be “free but not fair”, the conclusion of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), who partially monitored the 2018 election process. That’s the optimistic take. Others are fearful they will be neither free nor fair, so much so that a grassroots civic initiative called 20K22 has recruited more than 20,000 ballot counters – two for each of Hungary’s voting precincts – to be stationed at polling centres on election day with the aim of stopping any voting irregularities.

News from yesterday isn’t confidence-boosting either. Hungarian election officials reported a suspected case of voter fraud to the police. Bags full of completed ballots were found at a rubbish dump in north-western Romania, home to a large Hungarian minority who have the right to vote in Hungary’s elections. Images and videos shared by the opposition featured partially burnt ballots marked to support them. As of writing, no details have been provided of the actual perpetrators and their motives, and Orban has been quick to accuse the opposition of being behind the incident. Either way, it leaves a bad taste in the mouth.

We, the undersigned organisations, stand in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, but particularly Ukrainian journalists who now find themselves at the frontlines of a large-scale European war.

We unequivocally condemn the violence and aggression that puts thousands of our colleagues all over Ukraine in grave danger.

We call on the international community to provide any possible assistance to those who are taking on the brave role of reporting from the war zone that is now Ukraine.

We condemn the physical violence, the cyberattacks, disinformation and all other weapons employed by the aggressor against the free and democratic Ukrainian press.

We also stand in solidarity with independent Russian media who continue to report the truth in unprecedented conditions.

Join the statement of support for Ukraine by signing it here.

#Журналісти_Важливі

Signed:

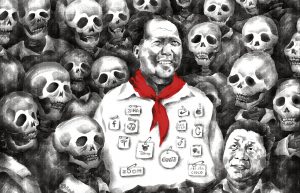

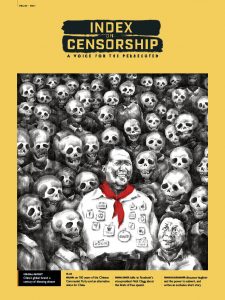

Illustration: Badiucao

Index looks back on 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and how their censorship laws continue to shape the lives of people around the world and threaten their right to free speech. Inside this edition are articles by exiled writer Ma Jian and an interview with Facebook’s vice-president for global affairs, former UK deputy Prime minister Nick Clegg; as well as an exclusive short story from acclaimed writer Shalom Auslander.

Acting editor Martin Bright said: “I am delighted to introduce the latest edition of Index which marks the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party.”

“This year also marks the 50th anniversary of the magazine and I am proud that we are continuing the founders’ legacy of opposition to totalitarianism.”

“In this Spring edition of Index we are particularly pleased to publish an exclusive essay by the celebrated Chinese writer Ma Jian, who suggests that an alternative tradition of tolerance and freedom is still possible.”

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

A century of silencing dissent by Martin Bright: We look at 100 years of the Chinese Communist Party and the methods of control that it has adapted to stifle free expression and spread its ideas throughout the world

The Index: Free expression round the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern

Fighting back against the menace of Slapps by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Governments continue to threaten journalists with vexatious law suits to stop critical reporting

Friendless Facebook by Sarah Sands: An interview with Facebook vice-president Nick Clegg about being a British liberal at the heart of the US tech giant

Standing up to a global giant by Steven Donziger: A lawyer who has gone head to head with the oil industry since 1993 at great personal cost tells his story

Fear and loathing in Belarus by Yahuen Merkis and Larysa Shchryakova: The crackdown on journalism has continued with arrests. Read the testimony of two reporters

Killed by the truth by Bilal Ahmad Pandow: Babar Qadri was one of Kashmir’s most strident voices, until he was gunned down in his garden

Cartoon by Ben Jennings: Arguments about the removal of statues cause a stir

The martial art of free speech by Ari Deller and Laura Janner-Klausner: The question of Cancel Culture continues to rage. Is it really a problem?

Ma Jian

Burning through censorship: Censorship-busting online organisation GreatFire celebrates its 10th anniversary

The party is your idol by Tianyu M. Fang: China’s propaganda is adapting to target young people

Past imperfect by Rachael Jolley: Four historians explain how the CCP shaped China and ask if globalisation will be its undoing

Turkey changes its tune by Kaya Genç: Uighur refugees living in Turkey find themselves victims of a change in foreign policy

The human face and the boot by Ma Jian: The acclaimed writer-in-exile reflects on 100 years of the CCP and its legacy of bloodshed

A moral hazard by Sally Gimson: Universities around the world and the CCP’s challenges to academic freedom

Director’s cuts by Chris Yeung: Hong Kong broadcaster RTHK has been squeezed by China’s tightening control

Beijing buys Africa’s silence by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Africa’s rich natural resources are being hoovered up by China

A new world order by Natasha Joseph: Journalist Azad Essa found when he wrote about China in Africa, his writing was silenced

A most unlikely ally by Stefan Pozzebon: Paraguay has long been an ally of Taiwan, but it’s paying an economic price

China’s artful dissident: A profile of our cover artist: the exiled cartoonist Badiucao.

Lies, damned lies and fake news by Nick Anstead: Fake news is rife, rampant and harmful. And we can only counter it by making sure that the truth is heard

Censorship? Hardly by Clive Priddle: Even the most controversial book usually finds a publisher after it has been turned down

A voice for the persecuted by Ruth Smeeth: As Index celebrates its 50 year anniversary, we note why free speech is still important

Collective ©ALEXANDER NANAU PRODUCTION

Don’t joke about Jesus by Shalom Auslander: An exclusive short story based on a joke by the acclaimed author of Mother for Dinner

Poet who haunts Ukraine by Steve Komarnyckyj: Vasyl Stus, the writer who remains a Ukrainian hero, 35 years after perishing in a Soviet gulag

The freedom of exile by Khaled Alesmael, Leah Cross: A young refugee Syrian writer on the love between Arab men

Forbidden love songs by Benjamin Lynch: Iran’s underground pop music scene upsets the regime

Reviews: Saudi Arabia’s murder of Jamal Khashoggi, USA Gymnastics and healthcare in Romania: we review three new documentaries

War of the airwaves by Ian Burrell: The Chinese government faces difficulties with its propaganda network CGTN