Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]By Ciaran Willis, Lauren Brown and Samantha Chambers

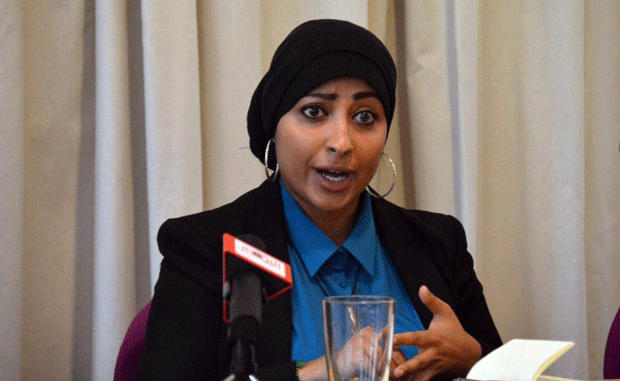

Zainab and Maryam al-Khawaja

The daughters of Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, the co-founder of Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, participated in a demonstration on Monday 9 April outside the Bahrain Embassy in London calling for his release on the seventh anniversary of his arrest.

Maryam and Zainab al-Khawaja joined NGOs and fellow supporters, as they chanted “free free Abdulhadi” and held placards with a picture of the Bahraini human rights activist.

It marked seven years since Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, founder of the 2012 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award-winning Bahrain Centre for Human Rights, was imprisoned for his involvement in peaceful pro-democracy protests that swept the country during the Arab Spring. On 9 April 2011 twenty masked men broke into his house, dragged him down the stairs and arrested him in front of his family.

Bahrain has a poor track record on human rights, with many reports of torture and human rights defenders in jail. Al- Khawaja was part of the Bahrain 13, a group of journalists and activists who faced unfair trials following the unrest.

During his time in prison, Al-Khawaja has been tortured, sexually abused and admitted to hospital requiring surgery on a broken jaw.

His daughter Maryam al-Khawaja was imprisoned in Bahrain for a year before leaving the country in 2014. She faces prosecution on charges including insulting the king and defamation. She told Index: “For me, this isn’t just about my dad, it’s a reminder that we have thousands of prisoners in Bahrain, and we need to remember all of them, and we need to be fighting on behalf of all of them. These are all prisoners of conscience.”

A number of prominent Bahraini campaigners took part in the demonstration.

Jawad Fairooz, a former Bahrain MP and president of SALAM for Democracy and Human Rights, said: “We’re here to support Abdulhadi as a symbol of the demand of the people of Bahrain who want to live in the country with dignity and freedom.”

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy and an activist who fled the country following torture, said: “I’m proud to belong to a nation that Abdulhadi is a part of. Abdulhadi to me is one of the most inspirational individuals.”

Cat Lucas, programme manager at English Pen’s Writers at Risk initiative, said that the government could be doing a lot more to challenge what is going on in Bahrain. She hopes the Bahraini Embassy will finally act, not just in the case of al-Khawaja, “but in the case of lots of writers and activists who are imprisoned for their peaceful human rights activities”.

Protesters have gathered outside the Embassy once a month since January 2018 to highlight the dire human rights situation and ask the UK government to take action.

Al- Khawaja’s daughter Zainab called on the UK to hold the Bahraini regime accountable: “Major governments are still supporting the Bahraini regime with weapons and political training. They’re the people behind them. I can feel as angry here as I would protesting in Bahrain, because I know what the government here is responsible for. I know one of the reasons people are being killed and tortured in Bahrain, including my father, is the support from the British and American governments.”

A group of NGOs, including Index on Censorship and Pen International, signed a letter last week calling on Bahrain to cease its abuse of fundamental human rights.They asked the authorities to immediately and unconditionally free Abdulhadi, provide proper access to medical care and allow international NGOs and journalists access to Bahrain.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8lkS7Fsyqso”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1523361455279-ef10ef07-647f-1″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Back Row from left: Adam Rajab, Malak Rajab and Nabeel Rajab. Front Row from left: Sumaya Rajab and Zainab Alkhawaja. (Photo: Adam Rajab)

Human rights defenders often confront obstacles that make their work difficult. This is especially true in Bahrain, where the Sunni monarchy and government have been bent on silencing all opposition ever since the Arab Spring when tens of thousands of Bahraini citizens protested for democratic reform.

In recent months, the nation’s only independent news outlet, Al Wasat, was shuttered and prominent human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was sentenced to two years in prison for “spreading fake news”.

The families of activists suffer along with their loved ones and are often targeted with official harassment: detention, loss of employment, beatings and harassment. Each case is an individual story of a struggle for freedom.

A result of actions

Members of Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei’s family have been harassed and detained due to his ongoing campaigning for democracy and human rights in Bahrain. Most recently his mother-in-law and brother-in-law were detained while Alwadaei attended the United Nations Human Rights Council in March.

Alwadaei, director of advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, is no stranger to detention: he was arrested twice in 2011 and served a six-month sentence in a Bahraini jail. He found asylum in the UK in July 2012. In February 2015, Alwadaei was among 72 Bahraini citizens to be stripped of their citizenship.

Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei with his son Yousif (Photo: Moosa Satrawi)

In October 2016, Alwadaei’s wife and infant son Yousif also faced official harassment as they tried to leave Bahrain to join Alwadaei in the UK. His wife was arrested at the airport and held overnight, during which time she was ill-treated. It was not until a few months later that she and her son were able to leave the country.

Other members Alwadaei’s family, including his sister, have also faced interrogations.

When asked how he continues campaigning under these circumstances, Alwadaei told index: “We can only get through this by sticking together and staying strong. It’s important to have a supportive family. The potential for arrest and torture is something they know and have to be willing to sacrifice.”

He added that he is balancing his efforts to get his mother-in-law out of prison while continuing his work in activism. “It’s hard but this is the right thing to do.”

“The oppression or torture aims to do one thing: to break your will because you’re not ready for the consequences,” Alwadaei said. “This is the state they want to leave you in. They want you to be broken and this is why we keep going.”

A life-long struggle

Maryam Al-Khawaja has been preparing for and participating in the struggle for human rights her entire life.

As a young child growing up in Denmark, she and her three sisters attended an English-speaking school, but the Al-Khawaja family knew they were only in the country temporarily. Her mother and father had been exiled for speaking out in Bahrain.

At a very young age, she remembers her parents asking her and her siblings before bed: “What have you done today to make the world a better place?” She told Index that her father wouldn’t help them answer the question because he wanted them to think about how the world could be. She remembers dinner conversations alive with politics and philosophical discussion about whether having false hope or no hope was better.

Around the 7th or 8th grade, Al-Khawaja knew wanted to be like her father when she grew up; she wanted to be an activist.

Maryam Al-Khawaja (Photo: David Coscia for Index on Censorship)

Al-Khawaja was 14 when her family returned to Bahrain in 2001. She recalls thinking her family was ready to take on the challenges and that the people of Bahrain would be ready to fight with them. But that was not the case. The country was tired of conflict and believed that the king’s promised reforms would be implemented. At the same time, activists were not popular among ordinary Bahrainis.

At college she said she was criticised by her classmates for speaking her mind about the state of their country, which caused her to lose interest in her father’s reform work. At the time, she asked him: “Why are you trying to change a situation for people who don’t want to change it for themselves?” His response was simple: “Someday you will understand.”

It wasn’t until 2011 during the Arab Spring protests that she developed a newfound respect for her father and was ashamed of herself for ever doubting him. She admits growing up in Denmark made her think fighting for human rights would be easy. When her father, along with 12 other leaders of the uprising, was arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment, she found that a life of campaigning isn’t so effortless.

During our conversation, Al-Khawaja jumped off the phone for a few minutes to take a call from her father. She had not heard from him in over three weeks and said their phone calls are always random and typically short as it is normal for the line to be cut if anything about the Bahrain government or any activist’s work is mentioned.

Until recently, her mother and sisters in Bahrain had not seen her father since February as their requests to visit have continually been denied. Al-Khawaja has not seen her father since 2014 as there are multiple fabricated charges against her that would mean imprisonment if she returned to the country.

Since her father’s imprisonment, Al-Khawaja and her older sister Zainab have been active in the push for human rights and freedom of speech in Bahrain. She says her father has two main characteristics as an activist: a fierce advocate and a fiery speaker. She explained that she and Zainab are the two parts to that whole: Al-Khawaja as the advocate and Zainab as the speaker.

Al-Khawaja said the work of her father and her sister Zainab has been tough for her two younger sisters. One sister had the highest scores in nursing school in Bahrain and graduation seemed to promise a job. But the paperwork from the government granting her access to work never came. She’s been waiting nearly eight years without a job. Al-Khawaja said it’s difficult for her family members when they’re in jail as they have to “take care of us when we cannot take care of ourselves”.

Her mother also felt the effects of the family member’s work when she was fired from her private school teaching job where she was the head of guidance.

A cause for celebrity status never wanted

Adam Rajab realised when he was young that his father Nabeel wasn’t like other dads. “I was so confused ‘why does my father work all day, while other fathers have certain working hours?,’” he told Index.

During a holiday he asked his father to take a break for a day. His father answered: “My colleagues are in prison. I can’t stop my work because they are suffering behind bars.”

In 2006, when Rajab was nine years old, he vividly recalls seeing his father come home bleeding from his head with a swollen and bruised back. “I was shocked and terrified but my father continued protesting like nothing had happened,” he said. “This was terrifying to me but the determination and fearlessness I saw in him really inspired me.”

In 2011 Nabeel Rajab’s work became well known. He appeared on TV and was the first activist to use social media to support the revolution then sweeping Bahrain. “Wherever we went, people would stop him and start taking pictures,” Adam said, adding that the strange situation was a shock to the family. “It started to become difficult because we couldn’t enjoy a private life like we used to.”

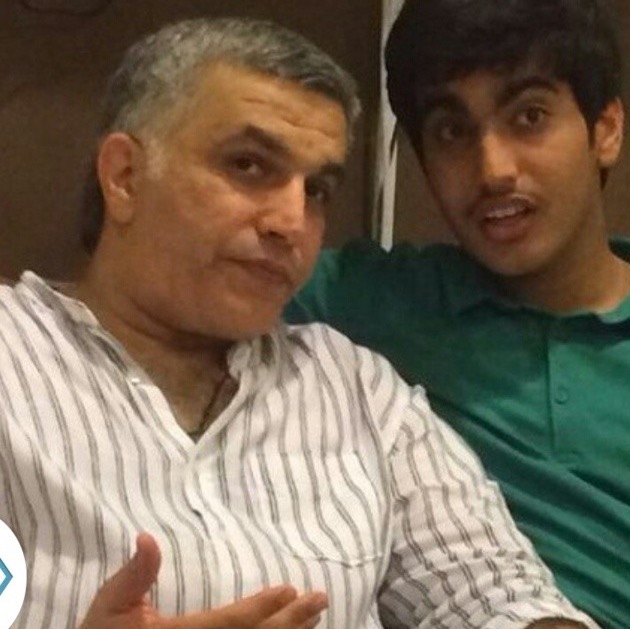

Nabeel Rajab with his son Adam Rajab

As a leader of the movement, Rajab’s father has become a face leaders around the world recognise but do little about. For years he has been in and out of jail. On 10 July 2017 he was sentenced to two years in prison for “broadcasting fake news”.

Although no one in the family has been arrested, his mother was harassed at her government job and then fired. Rajab and his sister have also faced harassment in school.

Rajab and his father have a very close relationship so the imprisonment has not been easy. “I haven’t seen him for more than a year now and he faces more charges which probably means more prison sentences,” Rajab said. “I find it difficult to enjoy anything while he is locked up in a cell and deprived of life, but as he taught me, the spirit is always up.”

Rajab wants his father to free and for them to live like any other ordinary family, but this does not take away from how proud he is or the strength of his belief in his father’s cause.

An open ended sentence

It’s difficult to imagine the emotions these activists and their families go through on a daily basis. A psychologist from the Refer Self Counselling Psychology Practice explained to Index that having a family member with a sentence with a sure release date is one case but when trials or release dates are postponed time and time again as they are in Bahrain, it is much more difficult. “We are rational problem solvers but not good with the unpredictable.”

The psychologist explained the situation in Bahrain is unlike what most with family members behind bars will ever experience. False hope puts an even greater emotional strain on loved ones.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1503052292764-bb1a6c59-5e91-2″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Norwegian musician Moddi’s new album, Unsongs, is made up of renditions of songs from around the world that had been banned, censored or silenced. Unsongs includes cover versions of songs from countries including China, Russia, Mexico and Vietnam, on topics such as drugs, war and religion.

Index on Censorship caught up with Moddi on Twitter to find out more.

To kick off our Twitter Q&A with @moddimusikk: Where did the idea for your new album, Unsongs, come from? #WithTheBanned pic.twitter.com/REWUt4tvxd

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship It all began with a song about the Israeli officer Eli Geva, who refused to lead his forces into Beirut in 1982.

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship The Norwegian singer Birgitte Grimstad heard the story of the officer, and had a song written about him.

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship She didn’t perform it though – it was considered “too controversial” at the time. And so it wasn’t sung for 32 years.

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship I heard the song 32 yrs after, then the snowball started rolling. There’s so much out there never played! #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

With so many banned or censored songs to choose from, how did you narrow it down to just 12? @moddimusikk #WithTheBanned

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship First of all: 12 songs does not represent the huge amount of censored art out there. They’re just examples. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship I wanted to choose 12 songs that represented 12 different forms of censorship. 12 different perspectives. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Murder, imprisonment, radio bans, social pressure, self-censorship. Different, but equally important. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship I believe it is a great mistake to consider the brutal forms of suppression more worthy of our attention. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship So basically, I chose 12 songs to show the diversity of the phenomenon. I could have made 12 albums though. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship @moddimusikk It must have been hard to pick only 12 songs, what was your favourite song that didn’t make the final cut?

— Sara French (@FrenchiedMuse) September 29, 2016

@FrenchiedMuse @IndexCensorship Oh, that’s probably something Kurdish, e.g. this masterpiece: https://t.co/MELFeWcIHa. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@FrenchiedMuse Have no idea what the lyrics say though. It’s always a little like Christmas eve. @IndexCensorship #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@FrenchiedMuse Another candidate is from the Iranian revolution https://t.co/WejoFpEzK8 but was too difficult to translate @IndexCensorship

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@moddimusikk have you ever heard a song so offensive you’ve thought ‘actually yeah, ok that should definitely be banned’ #withthebanned

— James Green (@JamesGreen6) September 29, 2016

@JamesGreen6 I considered some neo-nazi music for the album, but seriously, those words hurt physically to sing. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@JamesGreen6 Nonetheless not sure if long prison sentences is the right response. But that of course is a long debate.

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

How did Index on Censorship magazine help you find inspiration for the album? @moddimusikk #WithTheBanned

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Index helped me grasp the diversity of the issue. At first I only looked to Jara, Biermann…the classics. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Index helped me grasp the diversity of the issue. At first I only looked to Jara, Biermann…the classics. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Must most important: Orgs such as Index helped me understand that this is really an important topic. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship At first it was a hobby project. In the end it felt like a small part of a big movement. That helped. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

You tried to film the video for your version of @pussyrrriot‘s Punk Prayer in Russia but failed. What happened? @moddimusikk #WithTheBanned

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Yes, I seriously considered going to Russia to sing in solidarity with @pussyrrriot. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship I settled for the second best: singing it on the Russian border. There’s a beautiful old stone church there. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Unfortunately the parish did not approve and so the video had to be filmed on the church steps. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship It was minus five and stormy, ubearably cold, but felt good afterwards. @pussyrrriot‘s song it a true gem! #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Must say I’m disappointed with the Norwegian church though. I genuinely thought this song would be welcome. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship PS: The video turned out really well. https://t.co/YRdnimuycB @pussyrrriot

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

What was the hardest journey to make when visiting one of the original songwriters? #WithTheBanned

— ΛSHΣR ΛLΣXΛNDΣR (@AsherAlexander) September 29, 2016

@AsherAlexander Vietnam. Very confusing. Officially he was allowed to have visitors but in reality we were unwelcome. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@AsherAlexander Also the language and culture barriers were significant. But the meeting was still incredibly inspiring. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@AsherAlexander And in general: For a white, Norwegian boy, meeting with the genuinely banned has really been an eye-opener. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

#WithTheBanned Besides being a censored song, why did you choose a narcocorrido as part of the album? What caught your attention?

— Verito (@Veritokun) September 29, 2016

@Veritokun @IndexCensorship The double meaning! To me, who know that it is a narcocorrido, the underlying metaphor is obvious.#WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@Veritokun @IndexCensorship But to children and to many others, it may sound almost like a normal farm song. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@Veritokun @IndexCensorship The narcocororrido genre is terrible, but the way it avoided getting banned is – in this context – inspiring.

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@moddimusikk if you had to write a protest song, like Punk Prayer, what regime would you be challenging/ trying to change #WithTheBanned

— Ethan Beer (@EthanDuffmanB) September 29, 2016

@EthanDuffmanB My own, Norway! Protest is always best from inside. #WithTheBanned @IndexCensorship

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@EthanDuffmanB I’m not trying to change other countries, but presenting songs where others have tried. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@EthanDuffmanB Hopefully it can inspire other musicians across the globe to do the same. I know it has changed me, at least. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

How did your experience cancelling a concert in Tel Aviv change your approach to music? @moddimusikk #WithTheBanned

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship It made me realise that everything – even singing a love song – is political. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship In a conflict, remaining silent gives strength to the dominant side. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship And in this context, singing love songs and songs about the sea was equal to remaining silent. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship When I discovered “Eli Geva”, I felt that finally there was a song – a message – which was stronger than its own context.

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship When I write my own songs in the future, that will always be something I’ll aspire towards. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Like the songwriter Richard Burgess said “I could have written a song that she would have been allowed to perform…

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship …but I don’t think it would have been as good a song.” #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

What were the main things you learned about censorship when making Unsongs? @moddimusikk #WithTheBanned

— Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Censorship, in one form or anohter, is everywhere, all times, and it comes in different shapes. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship And it isn’t only states and religious authorities that are behind it. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship Basically, whereever there is power, there is also censorship. Those two seem to be mutually constituitive. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship So in a way, this project of interpreting banned songs is a case study of challenging power through music. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

@IndexCensorship As a young musician, that has probably been the most important lesson: That music CAN still be powerful. #WithTheBanned

— Pål Moddi Knutsen (@moddimusikk) September 29, 2016

To mark the release of Unsongs, Index on Censorship is proud to announce a special series of appearances by currently banned voices from around the world.

Moddi will hand over the stage at three of the biggest gigs on his current European tour to unleash the power of free expression, replacing the support band with the genuinely banned.

In Amsterdam on 1 October, Maryam Al-Khawaja will share her and her family’s story of imprisonment and exile in the struggle for democracy in Bahrain. In London on 3 October, Vanessa Berhe will speak about life in the prison state of Eritrea and her campaign One Day Seyoum fighting to free her journalist uncle Seyoum Tsehaye who has been in jail for 15 years. In Berlin on 6 October, Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently will tell how the Syrian civil war has destroyed the free expression of a generation. Co-founder Abdalaziz Alhamza will share the story of how and why he co-founded it inside IS-controlled territory.

To mark the release of Norwegian musician Moddi’s new album, Unsongs, Index on Censorship is proud to announce a special series of appearances by currently banned voices from around the world.

Moddi will hand over the stage at three of the biggest gigs on his current European tour to unleash the power of free expression, replacing the support band with the genuinely banned.

In Amsterdam on 1 October, Maryam Al-Khawaja will share her and her family’s story of imprisonment and exile in the struggle for democracy in Bahrain. In London on 3 October, Vanessa Berhe will speak about life in the prison state of Eritrea and her campaign One Day Seyoum fighting to free her journalist uncle Seyoum Tsehaye who has been in jail for 15 years. In Berlin on 6 October, Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently will tell how the Syrian civil war has destroyed the free expression of a generation. Co-founder Abdalaziz Alhamza will share the story of how and why he co-founded it inside IS-controlled territory.

“Unsongs is a remarkable collection of songs that have, at one stage, been banned, censored or silenced. The attempts to suppress them were as mild as an airplay ban and as brutal as murder. With great sensitivity and imagination, Norwegian singer-songwriter Moddi has given them new life and created a moving and eye-opening album. Unsongs simultaneously celebrates the censored and exposes the censors.” – Dorian Lynskey

Amsterdam, Jeruzalemkerk, Saturday 1 October, 8:30pm

The Banned: Maryam Al-Khawaja (Bahrain)

London, St. Giles-In-The-Fields, Monday 3 October, 8pm

The Banned: Vanessa Berhe (Eritrea)

Berlin, Silent Green, Thursday 6th October, 8pm

The Banned: Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently (Syria)

The series will be launched with a live Twitter chat with Moddi and Index on Censorship on Thursday 29 September at 3pm. Ask Moddi a question using the hashtag #WithTheBanned.