20 Feb 2017 | News and features, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship has recruited a new youth board to sit until June 2017. The group is made up of young students, journalists and legal professionals from countries including India, Hungary and the Republic of Ireland.

Each month, board members meet online to discuss freedom of expression issues around the world and complete an assignment that grows from that discussion. For their first task the board were asked to write a short bio and take a photo of themselves holding a quote that reflects their belief in free speech.

Fionnuala McRedmond – Dublin

Fionnuala McRedmond – Dublin

I graduated last June from the University of Cambridge with a degree in classics. I am now studying for a MSc in political theory at the London School of Economics. I was an active student journalist during my time at Cambridge, and it was there that I first developed an interest in the struggles of censorship and speech across the globe. The propensity for governments to censor speech and ideas is not a modern phenomenon. In ancient Rome book burning was not unheard of, and Cicero once expressed the all too familiar idea: “it is not permitted to say what one thinks… it is obviously permitted to keep silent.” Then, as much as now, free speech was the cornerstone of a healthy society. And then, as much as now, speech was censored by tyrannical power. I am particularly interested in the relationship between censorship and identity. In the past, and even more so now, people have been denied the right to share their words and ideas on the basis of ethnic, religious and political identity. Work by groups like Index on Censorship is crucial in protecting people’s right to speak, no matter who they are. I hope to better understand and develop these ideas with the Index on Censorship youth board.

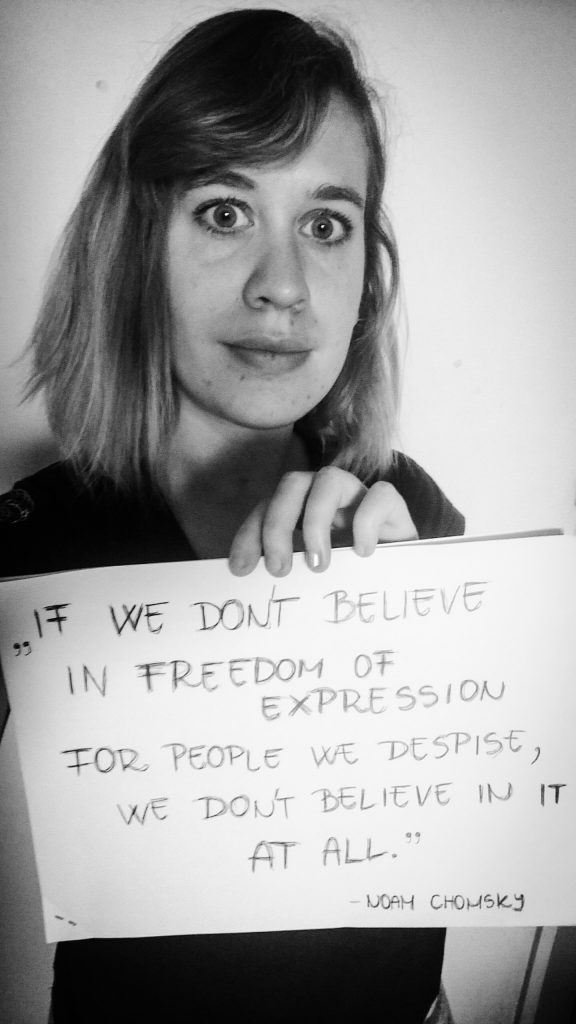

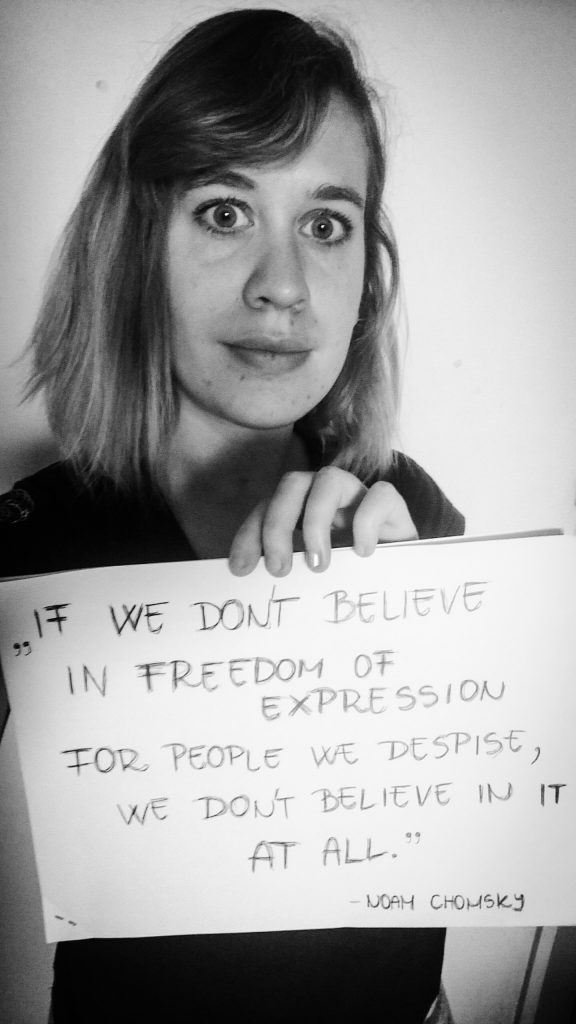

Júlia Bakó – Budapest

Júlia Bakó – Budapest

I am a Hungarian journalist, student and activist currently living in Budapest. After finishing my first degree in journalism, I have started studying international relations.

As a journalist and as someone who is deeply committed to human rights I am naturally drawn to freedom of expression and freedom of press issues. During the last couple of years I have worked with several NGOs and other organisations like Transparency International, Amnesty International, OSCE and Atlatszo.hu. I have dealt with corruption cases as an investigative journalist, I have studied human rights monitoring and – partly because of my studies, but mostly because of my personal interest and commitment – I have tried to explore freedom of expression and other issues not just in my own country, but all over the world, to find patterns, similarities and possible measures that could be taken either on a national or international level.

The quote I chose about freedom of expression says something what we sometimes tend to forget about. Being able to express our own opinions, however right they may seem to us, should never stop us from fighting for the rights of others to be able to act the same way, even though their opinions seem fundamentally different sometimes. Granting the chance to express opinions we do not agree with is what is able to create the diversity of thought, the debate about social issues and with that democracy itself.

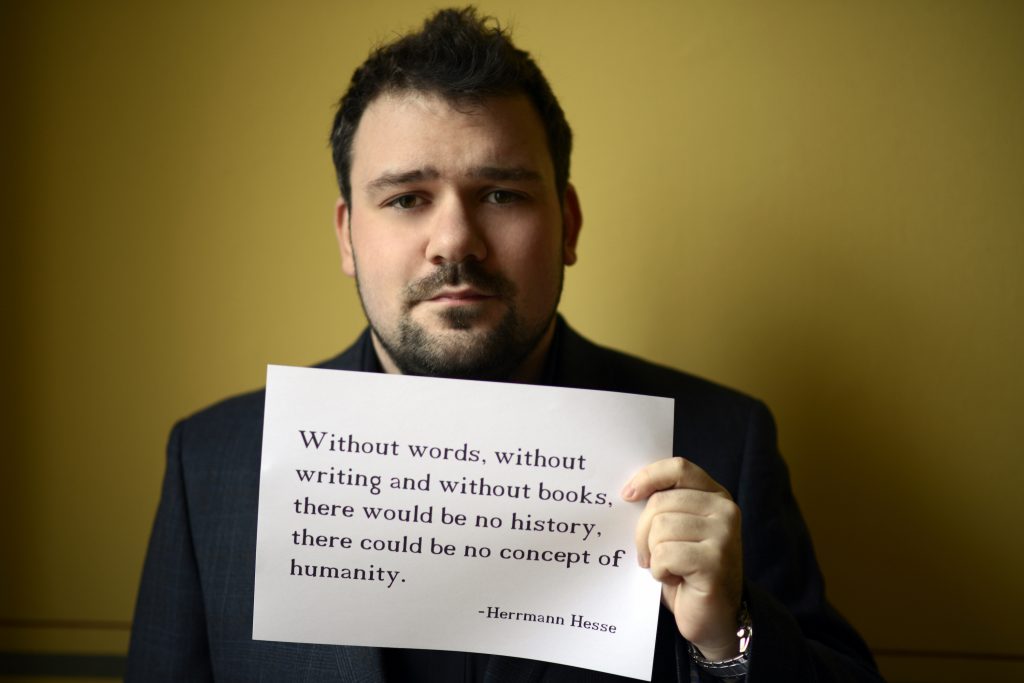

Samuel Earle – Paris

Samuel Earle – Paris

I currently live in Paris, where I am a freelance writer and English teacher.

I became interested in freedom of expression while studying politics at university – first at undergraduate and then at MSc level – and that continues today through my interest in journalism. What’s clear to me is that although freedom of expression is always valuable, the challenges it faces globally are never the same.

In the west, I think there is a complacency concerning freedom of expression: that stopping censorship is assumed to be enough. But I believe that in societies as unequal as our own, and where market forces reign, the value of freedom of expression can be diminished – as shown, for example, by the fake-news phenomenon.

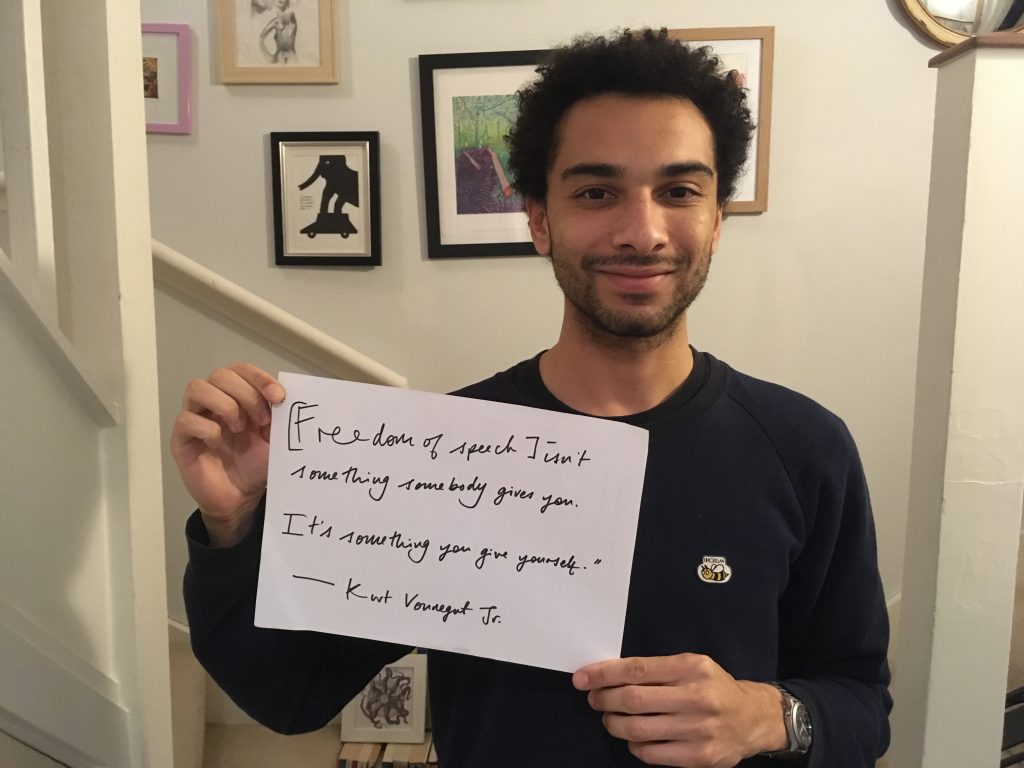

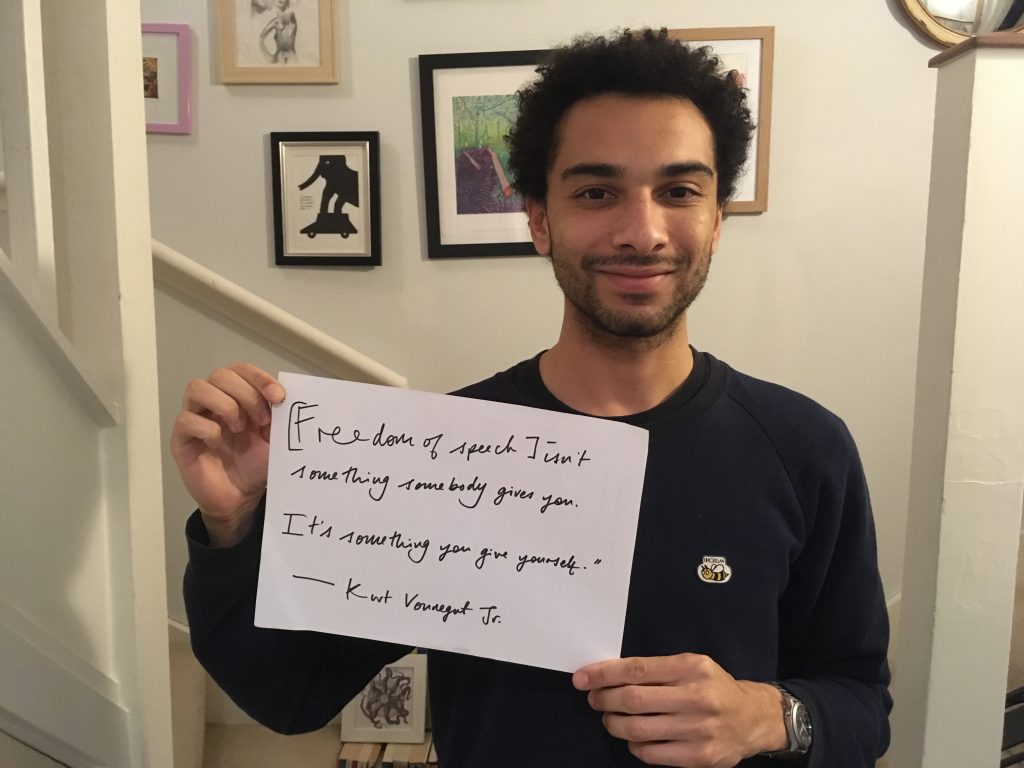

Samuel Rowe – London

Samuel Rowe – London

I am currently a postgraduate law student, having studied literature as an undergraduate in the UK and the USA. I hope to become a public law barrister, specialising in media and information law and human rights. Like the character in Kurt Vonnegut’s Hocus Pocus, I believe that the right to freedom of speech is innate. It is not a commodity; it is not something to be bargained with. My interest in issues surrounding freedom of speech directed my undergraduate dissertation, which focused on the western surveillance state. This sort of covert action can have the effect of creating an environment of self-censorship, and often has a disproportionate impact on marginalised communities. I looked at methods of resistance (of which there are many) to see how groups maintained freedom of speech under the gaze of the state. The suppression of freedom of speech is hardly a novel phenomenon and mass surveillance is just one way in which it is currently under threat. From White House officials calling disagreeable information “fake news” to irresponsible no platforming in universities, this is an era in which the limits and value of freedom of speech are being questioned. I believe that without freedom of speech, there can be no full interrogation of the evils which face us. And without interrogation, we risk losing sight of the full scope those evils might pose.

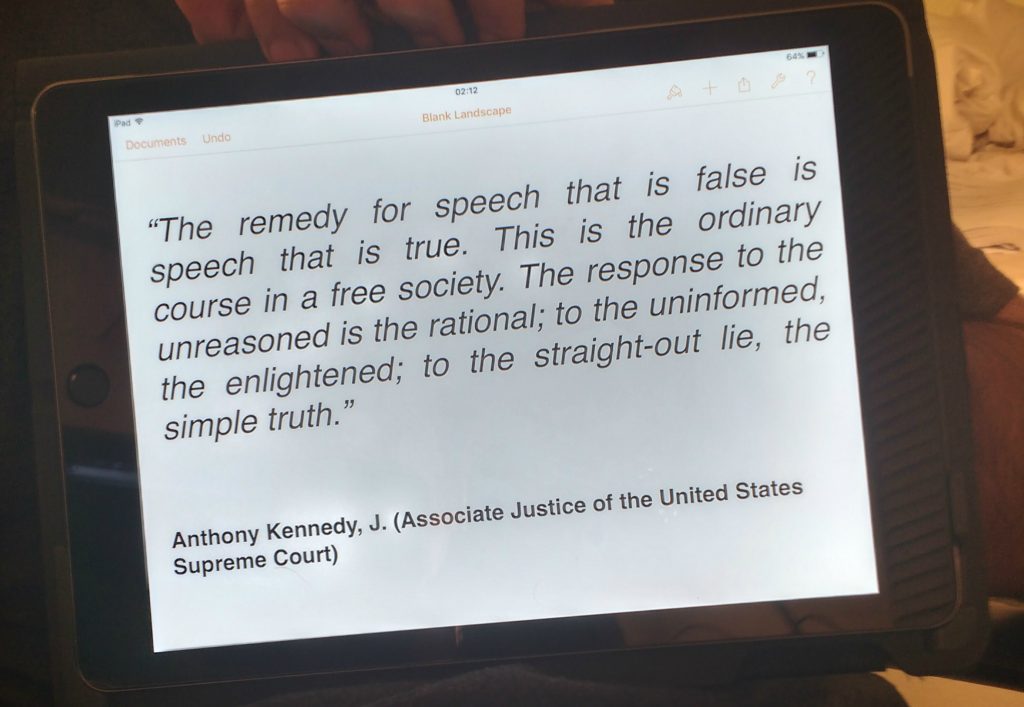

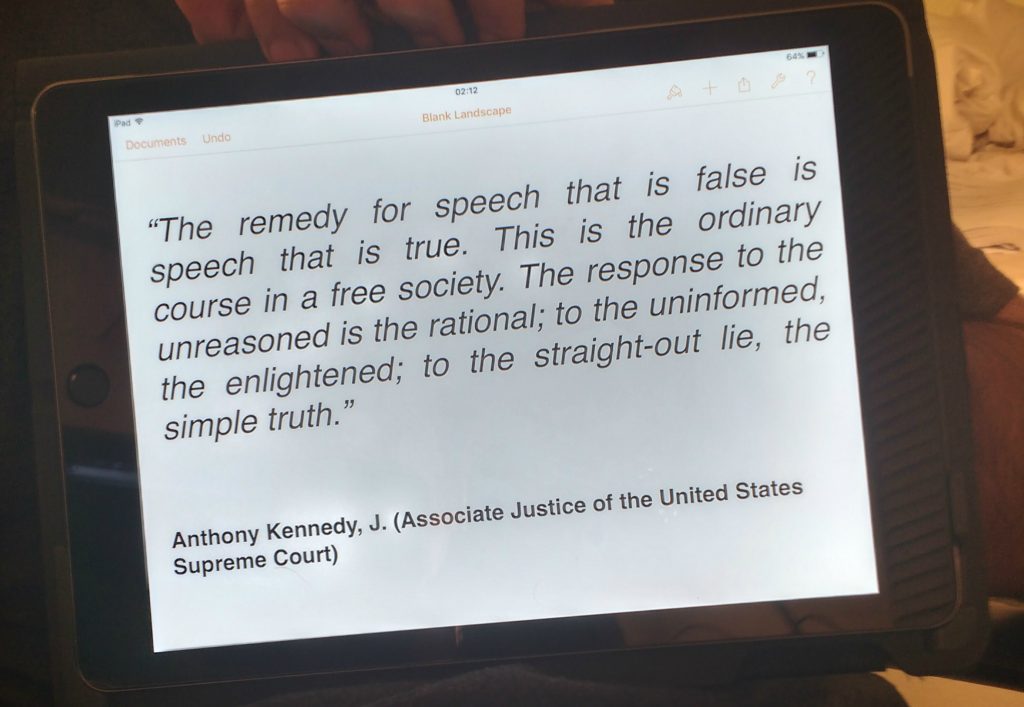

Tarun Krishnakumar – New Delhi

Tarun Krishnakumar – New Delhi

In recent times, there has been much concern expressed about the proliferation of “fake” news online and the impact it can have on democratic processes, politics and the public at large. These concerns have stirred various stakeholders – including governments, news media and internet intermediaries – into action. For instance, the German government recently declared fake news from Russia to be a significant threat to its upcoming elections. In a similar vein, internet giants like Google and Facebook – likely in the wake of unfavourable political outcomes – have been clamouring to show that they are willing to clamp down on content that is false or misleading.

In response to these developments, the quote I’ve selected manifests what, I feel, should be the appropriate response to fake speech: more “non-fake” speech – and not more regulation. While many justifications to clamp down on fake news may be well-intentioned, the history of regulating speech has shown us that inserting an intermediary into a conversation creates unintended and harmful consequences for free speech. Often this manifests as overt censorship while, in other cases, it is the creation of private arbiters of what may or may not be said on a platform – a more covert and creeping harm. Given the subjectivity in judging what news is “fake”, the debate also presents an excuse for regimes to tighten existing censorship controls or establish new ones.

The internet has given everyone an opportunity to have an equal say. This must be preserved at all costs. Fake news must be countered not through bans, blocking or regulation but by targeting the societal information asymmetries that allow it to flourish and creating conditions that facilitate society to produce more speech that is not “fake”. Policy efforts should focus on educating readers and providing them the tools to judge content for themselves – thereby minimising the effect of false or misleading content. For this, what is necessary is a culture of being exposed to a balanced diet of diverse content. When governments peddle nationalistic, religious, or political rhetoric in educational curricula and skew facts, little do they realise that they are creating the very conditions that allow “fake” news to flourish and have the harmful impacts that they complain of.

Sophia Smith-Galer – London

Sophia Smith-Galer – London

I’m a MA student studying broadcast journalism at City University in London. I studied Spanish and Arabic previously at Durham University and I’m particularly interested in how artists and writers overcome challenges to their freedom of expression in Latin America and the Middle East. As a singer I have always been intrigued by the imagery of a caged bird that sings despite its entrapment; Charlotte Bronte instead uses this metaphor to show how independent Jane Eyre has become by the end of the eponymous novel. Humans have always connected birds with freedom, or lack of – just look at Twitter’s logo – and so the quote really resonated with me.

Freedom of expression is particularly important to me as several countries that speak both of the languages I have dedicated years of study to continue to be plagued by tyrants and censors. I’m particularly interested addressing censorship in Latin America and the Middle East, especially with regard to the arts, as I’m also a classical singer and keen art historian.

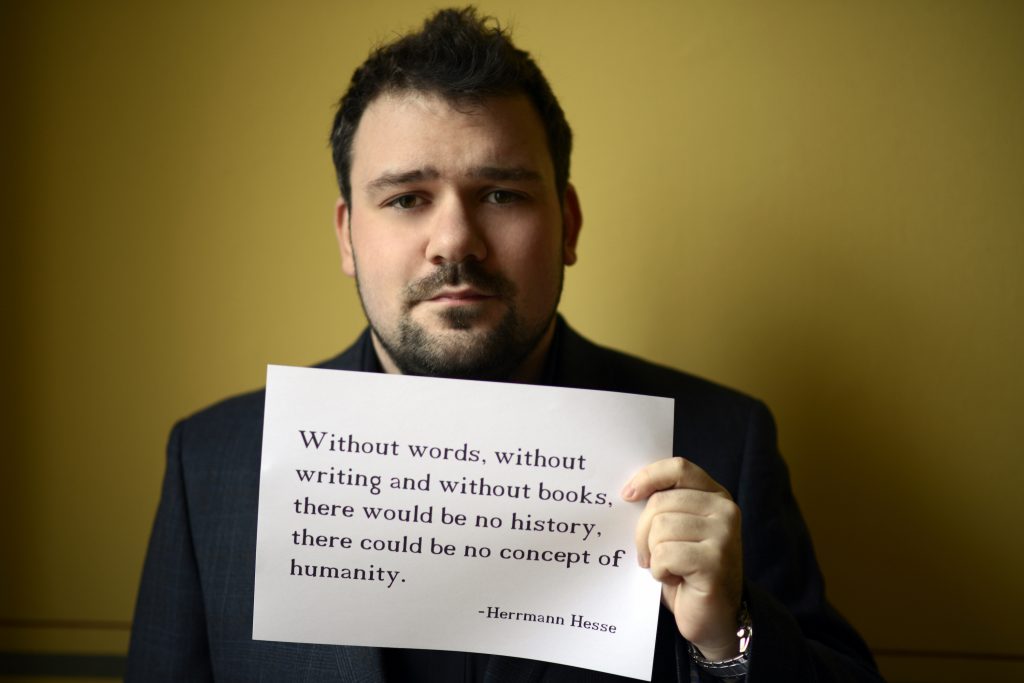

Constantin Eckner – St Andrews

Constantin Eckner – St Andrews

I am originally from Germany. I graduated from University of St Andrews with an MA degree in modern history. Currently, I am a PhD candidate specialising in human rights, asylum policy and the history of migration. Moreover, I have worked as a writer and journalist since I was 17 years old, covering a variety of topics over the years. Longer stays in cities like Budapest and Istanbul have raised my awareness for pressures exerted upon freedom of expression.

I chose this particular quote, because Hermann Hesse emphasised the importance of the written word and how it had an impact on the concept of humanity. In his time, Hesse was conscious that without writing it was not possible to express thoughts and spread ideas. Therefore, all those who fought the existence of the written word threatened humanity which was a frightening thought for a humanist like Hesse.

In a perfect world, every human being would live without fear of state censorship and potentially facing repercussions for the words they write—or for the pictures they draw, for the photos they shoot, for music they play.

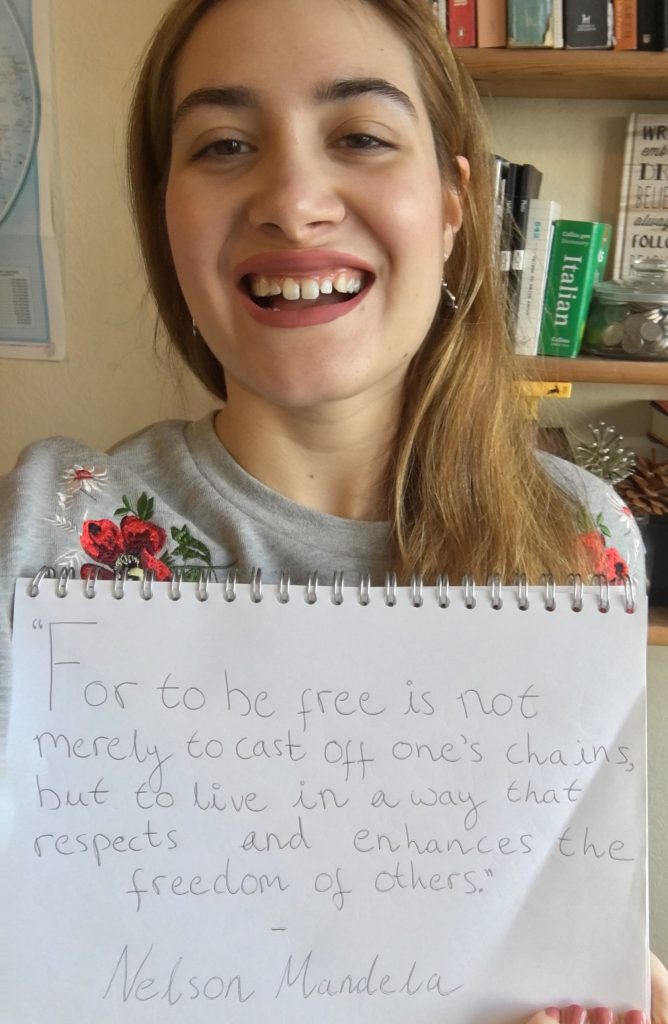

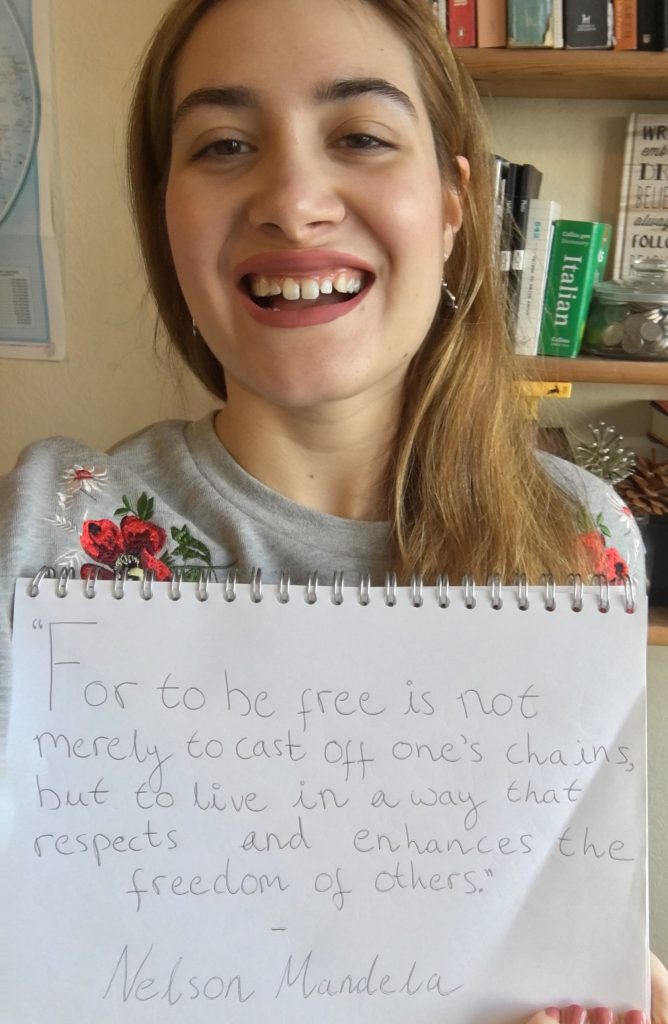

Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm

Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm

I’m half Brazilian and half Czech, raised in Sweden, but currently living in London where I work in communications for a mental health charity. I‘m also a Latin America correspondent for the International Press Foundation (IPF), a platform where young journalists get to write about stories that matter the most to them. It was during my time at Kingston University, studying journalism and French, when my interest in censorship and freedom of expression first emerged.

During my undergraduate studies I learned how important a free press is for a working democracy. It is a platform bringing together multiple voices, by sharing news, ideas and holding those in power to account. However, many journalists around the world suffer repression for simply doing their job and for using their right to free speech.

For me, Nelson Mandela‘s quote represents the importance of respecting and listening to each other, even with different views, but also highlighting the voices of those who are forced into silence.

Interviewing journalists from Venezuela and Pakistan, who face these types of constraints, has made me more engaged in sharing stories concerning freedom of expression, not only by journalists, but also by artists and activists. In the future, as a journalist, I want to focus on freedom of expression and by being part of the youth advisory board, I will be able to expand my knowledge and have great conversations with other young people who are passionate for justice and social change.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”More from the youth advisory board” category_id=”6514″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Feb 2017 | Awards

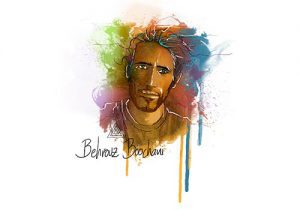

Behrouz Boochani has been shortlisted for a 2017 Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award in the journalism category.

Australia’s Media Entertainment Arts Alliance launched a campaign to open Australia’s borders to the Index Award-shortlisted Kurdish-Iranian journalist Behrouz Boochani, who is currently interned in Papua New Guinea.

The alliance is calling for the Australian government to resettle Boochani, along with actor Mehdi Savari and cartoonist ‘Eaten Fish’, from the Manus Island immigration detention centre to Australia.

“We believe that to continue to detain these three individuals without charge or trial undermines freedom of expression and the right to seek asylum”, according to a statement on the alliance’s website. “We urge you to allow them to be resettled in Australia so that they can live, work and contribute to Australian society.”

Boochani has been shortlisted in the journalism category of the 2017 Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards. Winners will be announced in April.

Boochani, who has been held at the detention centre since 2013, fled the city of Ilam in Iran after police raided the magazine he had co-founded, Kurdish Cultural Heritage. After less than a month in Australia he was forcibly relocated to the newly opened “refugee processing centre” in Papua New Guinea.

Preferring not to return home, Boochani reluctantly claimed asylum in Papua New Guinea alongside nearly 1000 other prisoners hoping to make it to Australia’s mainland. He has done his best to continue writing by passionately documenting his life in the restricted detention centre.

“I have never stopped thinking and working as a journalist”, says Boochani. “Despite attempts to silence me, I have not been silenced.”

He circumvented a ban on cell phones until 2016 by trading with the local residents in Papua New Guinea. Boochani was able to write many stories via the messenger app Whatsapp, even finding the time and space to shoot a feature film on his phone.

More than 100 journalists, actors, writers and cartoonists have collaborated in writing to the prime minister and immigration minister requesting that Boochani, Savari and Eaten Fish be resettled in Australia as soon as possible.

“WE, the undersigned, write as journalists, writers, cartoonists and performers to urge you to allow our colleagues Behrouz Boochani, Mehdi Savari, and ‘Eaten Fish’ to be resettled in Australia.

All three men have sought protection as refugees from Iran and are currently detained at the Manus Island Regional Processing Centre in Papua New Guinea which is operated on behalf of the Australian Government.

Well into the fourth year of their ordeal on Manus Island, and with delays and uncertainties in relation to any US resettlement deal, the three men remain in limbo. To varying degrees, the years of detention have severely impacted their mental and physical health.

- Behrouz Boochani, 33, is a Kurdish journalist. He has worked as a journalist and editor for several Iranian newspapers. On February 17, 2013, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps ransacked his offices in Ilam and arrested 11 of Boochani’s colleagues. Six were imprisoned. He has courageously continued to work as a journalist while in detention, and is a regular contributor to publications in Australia and overseas, often reporting on the situation and conditions on Manus Island. He has been recognised as a refugee and we urge you to allow him to reside in Australia to resume his career as a journalist. Boochani is a Main Case of PEN International, and has been recognised as a detained journalist by Reporters Without Borders. (RSF)

- Mehdi Savari, 31, is an Ahwazi Arab performer. As an actor, he has worked with numerous theatre troupes in many cities and villages in Iran, and performed for audiences in open public places. He was also well-known as the host of a satirical children’s TV show before fleeing Iran. Mehdi is a person of short stature and has met with severe discrimination over his life. His dwarfism has been exacerbated by the conditions and his treatment on Manus Island over the last three years, and he continues to suffer a range of physical ailments and indignities, as well as regular bouts of depression and chronic pain. As he has also been recognised as a refugee, we urge you to facilitate his resettlement in Australia. We also refer you to a resolution passed by the International Federation of Actors congress in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in September calling for his release from detention.

- Eaten Fish, 24, is a cartoonist and artist who prefers to be known by his nom-de-plume. He has recently received Cartoonists’ Rights Network International’s 2016 award for Courage in Editorial Cartooning. His application for refugee status has not been assessed. Since he was detained at Manus Island, he has been diagnosed with mental illnesses which have been compounded by his incarceration. We urge you to allow him to live in Australia until the final status of his claim can be determined.

As journalists, cartoonists, writers and performers, we are aware that the rights we enjoy are matched by a responsibility to challenge and confront tyranny and wrongdoing, to bear witness and uphold truth, and to reflect our society, even if sometimes unfavourably. We are privileged that in Australia we are able to pursue these ends without fear of persecution or threat to our personal liberty.

We believe that to continue to detain these three individuals without charge or trial undermines freedom of expression and the right to seek asylum. All three have courageously continued to practice their vocations on Manus Island despite their incarceration. We urge you to allow them to be resettled in Australia so that they can live, work and contribute to Australian society.

MEAA is joined in this letter by the the International Federation of Journalists, the International Federation of Actors, Reporters Without Borders, the Cartoonists’ Rights Network International, PEN International and members of the global network of the International Freedom of Expression Exchange.

We urge you to give the cases for resettlement of these three men serious consideration.”

20 Dec 2016 | Bahrain, Bahrain Letters, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]H.E. Zeid Ra’ad Zeid al-Hussein

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

Palais Wilson

52 rue des Pâquis

CH-1201 Geneva

Switzerland

CC: David Kaye, UN Special Rapporteur on Free Expression

Michele Forst, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders

Dear Mr. High Commissioner,

We, the undersigned human rights organizations, write to urge your office to urgently and publicly call on the Government of Bahrain to immediately and unconditionally release human rights defender Nabeel Rajab and drop the charges against him. His next, and likely final, trial date is scheduled for 28 December.

Nabeel Rajab’s trial is ongoing following the fifth extension of his court proceedings on 15 December. The further delay of Rajab’s trial to late December is additionally concerning due to the precedent established by the Bahraini government to take advantage of the time period around the end of year holidays to further violate human rights. For example, on 28 December 2014, the Government of Bahrain arrested and charged Sheikh Ali Salman, the Secretary General of the now dissolved Al-Wefaq political society, in relation to his free expression. Salman continues to serve a nine-year arbitrary prison sentence following his own lengthy trial.

This December, Nabeel Rajab could face up to 15 years in prison on charges regarding tweets and re-tweets from his account addressing torture in Bahrain’s Jau Prison, as well as criticizing Bahrain’s participation in Saudi Arabia-led military operations in Yemen. These military actions in Yemen, according to the United Nations, have so far been responsible for the deaths of more than 8,100 civilians, and include numerous unlawful airstrikes on markets, homes, hospitals, and schools. Rajab’s comments on Twitter about the Saudi-led coalition airstrikes in Yemen led to his arrest on 2 April 2015. Bahrain’s penal code provides for up to 10 years in prison for anyone who “deliberately announces in wartime false or malicious news, statements or rumors.”

Since June 2016, Rajab has been held in pre-trial detention, including two weeks of solitary confinement following his initial arrest.

Bahraini authorities released Rajab on 13 July 2015 in accordance with a royal pardon for previous Twitter-related charges following extensive international pressure. However, the Public Prosecution maintained this second round of charges against Rajab following his release and ordered his re-arrest nearly a year later on 13 June 2016. Rajab is also facing charges of “offending a foreign country” – Saudi Arabia – and “offending national institutions” for his comments about the torture of inmates at Jau Prison in March 2015. In October 2016, after months of trial hearings, the court reopened his case for investigation rather than dismissing the charges against him due to the lack of evidence.

Moreover, the government brought an additional charge against Rajab in relation to an open letter published in the New York Times on 4 September 2016. The Bahraini authorities immediately responded by charging Rajab with “undermining the prestige of the state.”

Since June 2016, Rajab has been held in pre-trial detention, including two weeks of solitary confinement following his initial arrest. The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for Non-Custodial Measures state that “pre-trial detention shall be used as a means of last resort in criminal proceedings, with due regard for the investigation of the alleged offence and for the protection of society and the victim.” The government’s use of pretrial solitary confinement against Nabeel Rajab while prosecuting him for free expression is clearly an additional form of reprisal for his work as a human rights defender and is in breach of the UN’s standards for detention.

Nabeel Rajab is the co-founder and president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, the founding director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights, a Deputy Secretary General of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) from 2012 to 2016, and holds advisory positions with Human Rights Watch. Amnesty International considers him to be a prisoner of conscience. His human rights activism and his peaceful criticism of the Bahraini authorities have resulted in his imprisonment on two previous occasions, between May 2012 and May 2014, and between January 2015 and July 2015.

Mr. High Commissioner, your office has pursued and published a number of communications in relation to human rights abuses perpetuated against Nabeel Rajab. Yet with his likely final court appearance approaching, it is imperative, now more than ever, to use the weight of your office to publicly defend him. We therefore call on you to issue a public statement in defense of Nabeel Rajab as a human rights defender arbitrarily detained for his free and peaceful expression. We further urge you to publicly call on the Government of Bahrain to immediately and unconditionally release Rajab, and to drop all charges against him.

Sincerely,

- Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain

- Albanian Media Institute

- Amnesty International

- Article 19

- Association of Caribbean Media Workers

- Bahrain Center for Human Rights

- Bahrain Human Rights Society

- Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy

- Bahrain Press Association

- Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism

- Cambodian Center for Human Rights

- Canadian Journalists for Free Expression

- Center for Media Studies & Peace Building

- CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

- Digital Rights Foundation

- Electronic Frontier Foundation

- English PEN

- European-Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights

- European Center for Democracy and Human Rights

- Foro de Periodismo Argentino

- Foundation for Press Freedom – FLIP

- Free Media Movement

- Freedom Forum

- Freedom House

- Free Media Movement

- Globe International Center

- Gulf Centre for Human Rights

- Independent Journalism Center – Moldova

- Index on Censorship

- International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

- International Press Institute

- International Service for Human Rights

- Journaliste en danger

- Maharat Foundation

- MARCH

- Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance

- Media Institute of Southern Africa

- Media Watch

- National Union of Somali Journalists

- No Peace Without Justice

- Norwegian PEN

- OpenMedia

- Pacific Freedom Forum

- Pacific Island News Association

- Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms – MADA

- PEN American Center

- PEN Canada

- PEN International

- Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

- South East European Network for Professionalization of Media

- Vigilance pour la Démocratie et l’État Civique

- World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers

- World Organization Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Individuals:

Clive Stafford Smith OBE, Founder, Reprieve[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1482250766050-89540f7d-7e72-0″ taxonomies=”3368″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Dec 2016 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 45.04 Winter 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Contributors include Lily Cole, Daphne Selfe, Linda Grant, Bibi Russell, Katy Werlin, Jang Jin-sung, Maggie Alderson and Eliza Vitri Handayani”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at fashion and how people both express freedom through what they wear. But it also looks at how women in particular have their freedom of expression curtailed by rigid dress codes – whether they are women in Saudi Arabia who have to wear abayas by law or women in the UK and Canada whose employers insist they wear high heels shoes.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”82377″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Models Lily Cole and Daphne Selfe discuss why changes in society are reflected in the clothes we (are allowed) to wear. Maggie Alderson, former editor of Elle describes how she was arrested for being a punk rocker in the 1970s, while Eliza Vitri Handayani talks about how punks in Indonesia today are still persecuted for what they wear and how they look. Nigerian model and journalist Wana Udobang riffs on fashion in Nigeria and how she was snubbed by bouncers and waiters at a wedding for wearing the wrong clothes.

Ismail Einashe describes how traditional dress can be life-threatening for Oromos in Ethiopa, while Magela Baudoin delves into class and ethnic gradations in Bolivia and reveals that the way some women dress means they are discriminated against. Novelist Linda Grant describes how her Jewish immigrant parents used the way they dressed to try and fit into middle-class British society. Meanwhile Katy Werlin gives a historical perspective as she discusses how the 18th century French revolutionaries, known as sans-culottes, celebrated their peasant clothes as they overthrew the aristocratic regime.

Martin Rowson brings another perspective to fashion in his new cartoon which depicts a catwalk on which despots show off their latest costumes. Spot President-elect Donald Trump sporting a furry thong. Trump is also in US media expert Eric Alterman’s sights as he describes why journalists in the USA believe the new president will seek to challenge media freedoms guaranteed by the constitution. Turkish researchers Burak Bilgehan Özpek and Başak Yavcan investigate how the Turkish government is using state advertising to control the media.

We also publish an interview with Turkish intellectual, linguist and founder of a mathematics village Sevan Nişanyan. Our reporter communicated with him using notes smuggled out from the prison where he is serving a 16-year sentence on charges connected with freedom of speech. The culture section includes poems from a former North Korean propagandist Jang Jin-sung who defected to the South and now runs a website smuggling news out of North Korea. We also carry poems about the extraordinariness of everyday life from Brazilian author Paulo Scott and a never before seen English translation of a short story by legendary Argentine writer Haroldo Conti.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: FASHION RULES” css=”.vc_custom_1481731933773{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Dressing to oppress: why dress codes and freedom clash

The censors’ new clothes, by Rachael Jolley: Freedom is not about the amount of clothing you put on or take off, but about having the choice to do so

Fashion police, by Natasha Joseph: Some feel the miniskirt is a threat to the state in Uganda and women are getting attacked for wearing it

Wearing a T-shirt got me arrested, by

Maggie Alderson: Wearing punk clothes in 1970s London was dangerous, but now British teenagers can wear anything

Colour bars, by Magela Baudoin: Traditional clothing is still a sign of social status in Bolivia and wearing such clothes often leads to discrimination

Models of freedom, by Bibi Russell: Bangladeshi women are now vital to the economy but they are still restricted in their dress

The big cover-up, by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Women in Saudi Arabia and Yemen test how far they can customise what they are allowed to wear. Translation by Lucinda Byatt

Rebel with a totally fashionable cause, by Wana Udobang: A Nigerian model refuses to conform to stifling social expectations and sees the consequences

Stripsearch cartoon, by Martin Rowson: A fetching new range of despotwear

Ethiopia in crisis, closes down news, by Ismail Einashe The Oromo people use traditional clothing as a symbol of resistance and it is costing them their lives

Baggy trousers are revolting

, by Katy Werlin: The sans-culottes of the French revolution transformed peasant dress into a badge of honour

Muslim punks in mohawks attacked, by Eliza Vitri Handayani: Punks in Indonesia are persecuted but still manage to maintain a culture which stands up for difference

Design is the limit, by Jemimah Steinfeld: China is loosening up on personal freedoms including fashion, but designers still face some constraints

A modest proposal, by Kaya Genç: “Modest” dress codes are all the rage in Turkey as some turn their backs on the legacy of Atatürk

Uniformity rules, by Jan Fox: Prisoners often try to customise their uniforms but does stripping individuality make rehabilitation more difficult?

Keeping up appearances, by Linda Grant: Linda Grant’s immigrant family were upwardly mobile and bought clothes that showed their aspirations

Sewing it up, by Rachael Jolley: At 88 Daphne Selfe is Britain’s oldest supermodel. She talks about how fashion has changed in her lifetime

Style counsels, by Kieran Etoria-King: Model, activist and actor Lily Cole talks about how school girls customise their uniforms to give them a sense of individuality

Tall stories, by Sally Gimson: Wearing high heels is a way for some women to express freedom, while for others it’s a form of oppression

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Challenging media, by Eric Alterman: If his campaign is anything to go by, President Trump is likely to restrict freedom of the press

Living in limbo, by Marco Salustro: A journalist reveals the challenges of reporting from inhumane migrant detention camps in Libya

Follow the money, by

Burak Bilgehan Özpek and Başak Yavcan: The Turkish government is rewarding newspapers which favour its position with more state-sponsored advertising

Fighting for our festival

freedoms, by Peter Florence: Mutilated bodies, petitions and a citizen’s arrest: the director of the Hay literary festivals describes the trials and tribulations of his job

Barring the bard, by Jennifer Leong: Actor Jennifer Leong on confronting attempts to censor performances of Shakespeare around the world

Assessing Correa’s free

speech heritage, by Irene Caselli: The Ecuadorian president’s record on free speech is reviewed as his term in office comes to an end. He gave sanctuary to Wikileaks founder, Julian Assange, in the country’s London embassy but brought in restrictive media laws at home

Framed as spies, by Steven Borowiec: South Korean journalist Choi Seung-ho hit a national nerve when he exposed the security services for framing ordinary citizens as North Korean spies

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Back from the Amazon, by

Paulo Scott: Newly translated poems from Scott’s acclaimed collection, Even Without Money I Bought a New Skateboard. Interview by Kieran Etoria-King. Poems translated by Stefan Tobler

A story from the disappeared, by Haroldo Conti: Jon Lindsay Miles introduces a poignant short story, published in English for the first time, by the award- winning Argentine writer who disappeared in 1976. Translation also by Jon Lindsay Miles

Poems for Kim, by Jang Jin-sung: North Korean propagandist poet turned high profile defector talks about life within the world’s most secretive country. Interview by Sybil Jones

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Global view, by Jodie Ginsberg: Face-to-face encounters are still important and governments worldwide know that restricting travel continues to be an effective way of stifling voices

Index around the world, by

Kieran Etoria-King: Coverage of Index’s work over the last few months including exposing the difficulties of war reporting and our Mapping Media Freedom project

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Where’s our president? by

Kiri Kankhwende: Malawi’s journalists tease their president as part of a campaign to make the government more transparent

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Fionnuala McRedmond – Dublin

Fionnuala McRedmond – Dublin Júlia Bakó – Budapest

Júlia Bakó – Budapest Samuel Earle – Paris

Samuel Earle – Paris  Samuel Rowe – London

Samuel Rowe – London Tarun Krishnakumar – New Delhi

Tarun Krishnakumar – New Delhi Sophia Smith-Galer – London

Sophia Smith-Galer – London Constantin Eckner – St Andrews

Constantin Eckner – St Andrews Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm

Isabela Vrba Neves – Stockholm