Editor’s letter: A question of trust

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Why don’t we learn that censorship and lack of trust in society puts us all at risk, particularly in times of crisis, asks Rachael Jolley in the summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine”][vc_column_text]

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.

Censorship by the Chinese state that stopped the rest of the world finding out what was happening as early as it could have.

Surely this is one of the most compelling arguments against censorship that we have seen in our lifetimes. Showing that if we know about a risk, we are able to discuss, to explore, to research, to prepare, and to take measures to avoid it.

As Covid-19 spread through the world, the parallels with World War I and the Spanish Flu were obvious. Here was a dangerous disease that many countries refused to acknowledge, that doctors were prevented from speaking about and that, for a time, the public had no knowledge of.

In 2014, I asked leading public health professor Alan Maryon-Davis to write about World War I and the flu epidemic for this magazine, a lesson from history for today. He wrote: “We also know that it was the deadliest affliction ever visited upon humanity, killing at least 50 million people world- wide, probably nearer 100 million, several times more than [the] 15-20 million killed by the war itself – and more in a single year than the Black Death killed in a century.”

Maryon-Davis identified three weak links that could have incredibly dangerous consequences in the reaction to a pandemic.

One was that health workers on early cases might worry about reporting it (self- censorship); the second was that governments would worry about political/cultural consequences (political censorship); and the third was that a cloak of secrecy might be thrown over it (pure censorship). Check, check, check. It’s happened again.

Lessons learned from history? Practically nil.

As we move through the tracking phase of this pandemic, we need to recognise that public trust is an essential part of any response, and that public will comes from a belief in society – and a belief that it will act for the public good. Trust also comes from a belief that your government will not collect private information about you and use it without permission, or to your detriment.

Historically, those who fought for freedom of expression and speech also fought for the right to privacy: your right to keep information private – such as your religion or sexual orientation – and the right for you not to have an illegal search of your private papers or your home. Those rights came together in the US constitution because those who wrote it knew what it was like to be in a minority or a protester in a country which oppressed those who did not conform.

They fled those countries to find more freedom, and they sought to create legislation that would mean others could choose to be different, or to express offensive or difficult ideas. That might sound ridiculously ideal- istic, and of course it was – there are plenty of holes people can pick in the reality of US society – but those ideas are strong, and valid for today.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”In Turkey there are independent thinkers who believed that home was the last refuge where they could criticise the government”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The right to privacy (and with it the right to express a minority opinion) is often endangered by legislation that is introduced without due process during times of war or crisis.

And it is against this backdrop that activists, journalists, academics and others began to worry that during this pandemic we are, with- out really considering the consequences, giving away our privacy.

Governments around the world have often responded to the Covid-19 situation with diktats that remove an element of democratic governance, or threaten hard-fought-for freedoms, with very little opportunity for public debate.

India’s Justice H.R. Khanna, among others, famously warned that governments use a crisis to ignore the rule of law. “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

This feels like wisdom that’s fitting for the current fractured moment.

In Turkey, there are independent thinkers who believed that home was the last refuge where they could criticise the government or talk about a difference of opinion from the mainstream. The introduction of the Life Fits Home app could mean a severe erosion of that private space, as once they have input their ID numbers, the government will know exactly who is where, and with whom.

As Kaya Genç outlines in his article on p50, the question is: can they trust an autocratic state which could save their lives via contact-tracing not to come after them later for political reasons?

This is similar to the question being asked in Hong Kong by those who protest against the ongoing erosion of the freedom which ensured it was a very different place to live from China in the last two decades.

During the pandemic, there have been discussions about the dangers of sharing personal information with the government, and one Hong Kong citizen we interviewed for this issue outlined why.

“Of course, we’re willing to do what we can as a collective to stop the spread of Covid-19,” she said. “But the point is, we have no trust in the government now. That’s why I don’t want to trade my information with the government in return for a few face masks.”

Another said people were worried about an app that they were required to download if they left the city and wanted to return, asking: “Who knows what they’ll do with our data?”

Some governments have put in place legal checks and balances to give people more confidence, and to offer assurances that data will not be used for other means.

In South Korea, a law was amended after the 2015 Mers outbreak to give authorities extensive powers to demand phone location data, police CCTV footage and the records of corporations and individuals to trace contacts and track infections.

As Timandra Harkness outlines on p11, that same law specifies that “no information shall be used for any purpose other than conducting tasks related to infectious diseases under this act, and all the information shall be destroyed without delay when the relevant tasks are completed”.

In Australia, legislation restricts who may access data gathered by a Covid-19 app, how it may be used and how long it may be kept.

Other countries have done much less to offer legitimacy and transparency to the data- gathering processes in which they are asking the public to participate.

In the UK, for instance, there has been no sign of legislation outlining any restrictions on how data captured by its track and trace system, or expected Covid-19 app, will be restricted from other use, or even stopped from being sold on to third parties.

Requests to ask the public to add apps such as these come at the same time as we see rising numbers of drones being used to invade our private spaces, and potentially to track our movements or actions.

We also see a dramatic, mostly unregulated, increase in the use of facial recognition around the world, again taking a hammer to our rights to privacy, and ramping up surveillance.

US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote in the 1920s of those who wrote the early laws of his land: “They knew that order cannot be secured merely through fear of punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies, and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.”

Those who fear their privacy is under threat, and who worry about other consequences of being tracked and traced, are unlikely to feel confident in a society that takes away basic freedoms during times of crisis and does not put dramatic changes into place via a parliamentary process. Governments should take note that this threatens pathways to safety.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on macho male leaders

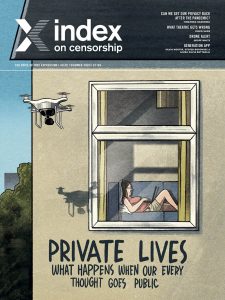

Index on Censorship’s summer 2020 issue is entitled Private Lives: What happens when our every thought goes public

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2020 magazine podcast featuring the world premiere of a lockdown playlet written and acted out exclusively for Index on Censorship by Katherine Parkinson

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]