The view from Hong Kong in 1997: an Index reading list

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Illustration from cartoonist tOad published today in response to the new law. twitter.com/t0adscroak, www.unsitesurinternet.fr

The National Security Law passed on 30 June in Hong Kong has dealt a massive blow to the city’s status as an autonomous region into which the Chinese government’s suppression of freedom of expression doesn’t encroach. The new law will criminalise “any act of secession, subversion of the central government, terrorism or collusion with foreign or external forces”.

Language like this, as those on the mainland may have experienced, could be manipulated to apply to any behaviour the Chinese government doesn’t like, leaving journalists, activists, protesters and campaigners at risk. Activists in Hong Kong have already begun to shut down their operations out of fear of reprisal in the wake of the law.

Since 1997, when Hong Kong was handed back to China having previously been a British colony, Hongkongers have enjoyed freedom of expression, including a flourishing free press, under the “one country, two systems” constitutional principle. As this principle begins to crumble, we look back at pieces published in Index magazine in 1997 which explored the implications of the handover and the future relationship between mainland China and Hong Kong.

Remade in Hong Kong

In this edited version of the speech given by Professor Helen Fung-Har Siu in Hong Kong in 1996, she explored the national identity of Hong Kongers and how it intersected with the oppressive nature of the Chinese authorities. In the years preceding the 1997 handover, the people of Hong Kong enjoyed freedom of expression; Siu noted that one in six people there marched in protest at the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre. Dissecting the socioeconomic developments in Hong Kong through the 1970s and 80s, Siu questioned how the region and its people, who are accustomed to independence from China, would adapt to its new relationship with the People’s Republic.

Hong Kong the floating city

Published in early 1997 in anticipation of the handover, Geremie R Barmé, author of Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader, wrote on the flow of popular culture from Hong Kong and Taiwan to mainland China through the 1980s. He explored how the lure of Beijing’s culture waned through the 70s, leading people to soak up the film and music coming from the south, despite attempts by the authorities to censor it. Hong Kong, independent from the Chinese authorities, acted as a conduit between the people in mainland China and Taiwan, and indeed the rest of the world. Barmé predicted that, as Hong Kong returned to China, the subsection of society supporting communist ideals would be brought to the fore by the mainland.

He wrote: “The patriotic significance of Hong Kong’s return to the mainland is lost on no-one. It is part of the final process of what the Communist authorities, and many people in China, see as the reunification of a divided nation.”

Citizen of the floating world

Ma Jian, an artist who left Beijing for Hong Kong in 1990, shared his feelings of liberation as he crossed the border and reflects on the suppression of his art on the mainland. Demanding rights and freedom from the Chinese authorities was, he wrote “like being on a battlefield”. Jian wrote that he would remain in Hong Kong after the handover, but projected a lack of optimism about his future freedoms.

“As we watch, incredulously, pre-ordained history advances, or rather, steps backwards to meet us,” he wrote. “No-one asks whether we accept the past, whether we can go and live the time we have already lived. It is as though, studying at middle school, we are suddenly sent back to kindergarten.”

Kingdom of the middlemen

In July 1998, Edward Lucie-Smith visited Hong Kong to find out how the city was acclimatising to the handover one year on. Finding local people unwilling to discuss at length the direction freedom of speech had taken, Lucie-Smith looked to global economic developments and how they could impact Hong Kong’s political future, and in turn the future of freedom of expression. Hong Kong faced an economic downturn in 1998, along with other so-called ‘tiger-economies’, meaning the Hong Kong Chinese elite, who were middlemen between the democratic forces in Hong Kong and the Chinese authorities, may have chosen to move to other parts of the world, leaving Hong Kong and its people more at risk of being ideologically swallowed up by the mainland.

He wrote: “The general feeling was that the British were handing over an economic jewel – a financial mechanism so successful and so finely tuned that the mainland Chinese government would be foolish to interfere with its functioning. But would it be able to resist tinkering, on ideological grounds, with the ‘special economic zone’ within China that Hong Kong was now to become?”

The way we live now

Published in January 1997, Jonathan Mirsky, then East Asia editor of The Times, wrote on how freedom of expression began to crumble in Hong Kong in anticipation of the handover. He described how news channels reported on China in a “vapid or grovelling” manner, to avoid attempts at censorship by Chinese representatives in Hong Kong.

Outspoken democratic politicians told Mirsky how their colleagues no longer wanted to be associated with them. Organisations were expected to plan celebrations for the handover, and comply. Mirsky predicted a dismal future for Hong Kong where loyalty to the Party would be an overriding expectation.

Breathing space

Charles Goddard, at the time of writing a member of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, discussed Hong Kong’s position as eyes on China for the rest of the world, where issues such as human rights abuses in mainland China could be discussed and dissidents from the Chinese authorities could find a relatively safe haven. Goddard, however, highlighted the dangers to journalists in Hong Kong reporting negatively about China, predicting that the status of the city as a place where freedom of expression could flourish would only diminish.

Ever the optimist

Liu Dawen, at the time of writing the editor of Front Line magazine, took an optimistic view of Hong Kong’s future, believing that the spirit of democracy would not wane.

“In the longer term, the Party cannot stem the ‘raging tide’ of democracy indefinitely either in Hong Kong or in the People’s Republic. When things reach a certain pitch, the pendulum must swing back in the opposite direction,” he wrote.

Tea and no sympathy

Charting the arrests and imprisonments of Chinese journalists, Asia-Pacific researcher for Reporters San Frontieres Barbara Vital-Durand painted a picture of China as a country which cracked down harshly on outspoken dissidents from the party line. She foreshadowed a world in which, post-handover, Chinese authorities would extend the jaws of censorship to crush Hong Kong journalists, and access to the internet on the mainland would be tightly controlled.

“Journalists’ organisations and free speech groups have been unsuccessful in getting the British authorities – or subsequently China’s Preparatory Working Committee (PWC) – to abolish several legislative measures which, if left in place, will provide the Chinese authorities with some powerful weapons to use against the media,” she wrote.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1593615252756-723f64f2-cdee-10″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

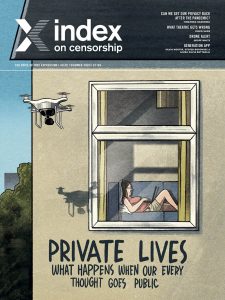

Contents – Private lives: What happens when our every thought goes public

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Katherine Parkinson, David Hare, Marina Lalovic, Geoff White and Timandra Harkness”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

In our In Focus section, we interview journalists in Serbia, Hungary and Kashmir who are trying to report the truth in places where the truth can be as dangerous, if not more, than Covid-19. And we have an interview with and poet from the playwright David Hare.

We have a very special culture section in this issue. Three playwrights have written short plays for the magazine around the theme of pandemics. V (formerly Eve Ensler), the author of The Vagina Monologues, takes you to the aftermath of a nuclear disaster; Katherine Parkinson of The IT Crowd writes about online dating during quarantine; Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily is inspired by recent events in his country in his chilling look at protest right now.

Buy a copy of the magazine from our online store here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][vc_column_text]

Virus masks a different threat by Hannah Leung and Jemimah Steinfeld: China is using Covid-19 responses and Hong Kong’s new security law to reduce freedoms in the city state

Back-up plan by Timandra Harkness: Don’t blindly give away more freedoms than you sign up for in the name of tackling the epidemic. They’re hard to reclaim

The eyes of the storm by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Spies are on the streets of Uganda making sure everyone abides by Covid-19 rules. They’re spying on political opposition too. A dispatch from Kampala

Generation app by Silvia Nortes, Steven Borowiec and Laura Silvia Battaglia: How do different generations feel about sharing personal data in order to tackle Covid-19? We ask people in South Korea, Spain and Italy

Zooming in on privacy concerns by Adam Aiken: Video app Zoom is surging in popularity. In our rush to stay connected, we need to make security checks and not reveal more than we think

Seeing what’s around the corner by Richard Wingfield: Facial recognition technology may be used to create immunity “passports” and other ways of tracking our health status. Are we watching?

Don’t just drone on by Geoff White: If drones are being used to spy on people breaking quarantine rules, what else could they be used for? We investigate

Sending a red signal by Tianyu M Fang: When a contact tracing app went wrong a journalist was forced to stay in their home in China

The not so secret garden by Tom Hodgkinson: Better think twice before bathing naked in the backyard. It’s not just your neighbours that might be watching you. Where next for privacy?

Hackers paradise by Stephen Woodman: Hackers across Latin America are taking advantage of the current crisis to access people’s personal data. If not protected it could spell disaster

Italy’s bad internet connection by Alessio Perrone: Italians have one of the lowest levels of digital skills in Europe and are struggling to understand implications of the new pandemic world

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: Ping! Don’t forget we’re watching you… everywhere

Less than social media by Stefano Pozzebon: El Salvador’s new leader takes a leaf out of the Trump playbook to use Twitter to crush freedoms

Nowhere left to hide by Kaya Genç: Privacy has been eroded in Turkey for many years now. People fear that tackling Covid-19 might take away their last private free space

Open book? by Somak Ghoshal: In India, where people are forced to download a tracking app to get paid, journalists are worried about it also being used to access their contacts

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Knife-edge politics by Marina Lalovic: An interview with Serbian journalist Ana Lalic, who forced the Serbian government to do a U-Turn

Stage right (and wrong) by Jemimah Steinfeld: The playwright David Hare talks to Index about a very 21st century form of censorship on the stage. Plus a poem of Hare’s published for the first time

Inside story: Hungary’s media silence by Viktória Serdült: What’s it like working as a journalist under the new rules introduced by Hungary’s Viktor Orbán? How hard is it to report?

Life under lockdown: A Kashmiri Journalist by Bilal Hussain: A Kashmiri journalist speaks about the difficulties – personal and professional – of living in the state with an internet shutdown during lockdown

The truth will out by John Lloyd: Journalists need to challenge themselves and fight for media freedoms that are being eroded by autocrats and tech companies

Extremists use virus to curb opposition by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Covid-19 is being used by religious militia as a recruitment tool in Yemen and Iraq. Speaking out as a secular voice is even more challenging

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Masking the truth by V: The writer of The Vagina Monologues (formerly known as Eve Ensler) speaks to Index about attacks on the truth. Plus a new version of her play about living in a nuclear wasteland

Time out by Katherine Parkinson: The star of The IT Crowd discusses online dating and introduces her new play, written for Index, that looks at love and deception online

Life in action by Lucien Bourjeily: The Lebanese director talks to Index about how police brutality has increased in his country and how that informed the story of his new play, published here for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]

Putting abuse on the map by Orna Herr: The coronavirus crisis has seen a huge rise in media attacks. Index has launched a map to track these

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Forced out of the closet by Jemimah Steinfeld: As people live out more of their lives online right now, our report highlights how LGBTQ dating apps can put people’s lives at risk

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Private lives

FEATURING

Issa Sikiti da Silva

Journalist

Issa Sikiti da Silva is an award-winning freelance journalist who has traveled extensively across Africa. Born in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, he has lived in South Africa and worked as a foreign correspondent in West Africa. His work has been published in nearly 40 media outlets

Katherine Parkinson

Actor and playwright

David Hare

Playwright

David Hare is a playwright and film-maker. He has written over thirty stage plays which include Plenty and Pravda (with Howard Brenton). For film and television, he has written nearly thirty screenplays which include Licking Hitler, The Hours, The Reader and Denial. In a millennial poll of the greatest plays of the 20th century, five of the top 100 were his