12 Sep 2016 | Awards, Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Press Releases

Also available in: Arabic, French, German, Italian, Mandarin, Portuguese (Brazil), Portuguese (Portugal), Russian, Spanish, Turkish

Index on Censorship opens nominations for the 2017 Freedom of Expression Awards and Fellowship

- Awards honour journalists, campaigners, digital activists and artists fighting censorship globally

- Nominate at indexoncensorship.org/nominations

- Nominations are open from 12 September to 11 October 2016

Beginning today, nominations for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellowship are open. Now in their 17th year, the awards honour some of the world’s most remarkable free expression heroes. Previous winners include Chinese digital activists GreatFire, Syrian cartoonist Ali Farzat and Angolan investigative journalist Rafael Marques de Morais.

Index invites the general public, civil society organisations, non-profit groups and media organisations to nominate anyone (individuals or organisations) who they believe should celebrated and supported in their work tackling censorship worldwide.

There are four categories in Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards:

- Arts for artists (any form) and arts producers whose work challenges repression and injustice and celebrates artistic free expression.

- Campaigning for activists and campaigners who have had a marked impact in fighting censorship and promoting freedom of expression.

- Digital Activism for innovative uses of technology to circumvent censorship and enable free and independent exchange of information.

- Journalism for courageous, high impact and determined journalism (any form) that exposes censorship and threats to free expression.

Relevant nominees are also eligible for the Music in Exile Fellowship, which supports musicians whose work is under threat.

As awards fellows, all winners receive one residential week of networking, advanced training and consultancy in London (April 2017) followed by 12 months of bespoke support to amplify and sustain their valuable work for free expression worldwide.

Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index, said: “The Freedom of Expression Awards not only showcase but also strengthen groups and individuals doing brave and brilliant work to enhance freedom of expression around the world. These are true heroes – people who often have to overcome immense obstacles and face great danger just for the right to express themselves. I urge everyone to nominate their free expression champion – make sure their voice is heard.”

The 2017 awards shortlist will be announced in late January. The winners will be announced in London at a gala ceremony on 19 April 2017 at The Unicorn Theatre.

For more information on the awards and fellowship, please contact [email protected] or call +44 (0)207 963 7262.

Also available in: Arabic, French, German, Italian, Mandarin, Portuguese (Brazil), Portuguese (Portugal), Russian, Spanish, Turkish

12 Sep 2016

Index on Censorship annonce l’ouverture des nominations pour l’obtention des prix et bourse de la liberté d’expression de l’année 2017.

- les récompenses sont attribuées aux journalistes, militants et activistes digitaux luttant contre la censure à un niveau mondial

- il est possible de soumettre ses nominations sur indexoncensorship.org/nominations

- ouverture des nominations du 12 septembre au 11 octobre 2016

A partir d’aujourd’hui, sont ouvertes les nominations pour la remise des prix et de la bourse de la liberté d’expression d’Index on Censorship. Depuis 17 ans maintenant, ces prix honorent quelques uns des héros de la liberté d’expression les plus remarquables. Parmi les gagnants des précédentes années, figurent le collectif Great Fire, activistes digitaux chinois, le caricaturiste syrien Ali Farzat ainsi que le journaliste d’investigation d’Angola Rafel Marques de Morais.

Dès à présennt, Index On Censorship invite le public en général, les organisations de la société civile, les associations à but non-lucratifs et autres organismes de media à nominer quiconque participe de la lutte contre la censure dans le monde et dont le travail mériterait d’être soutenu et célébré.

Il existe quatre catégories pouvant prétendre aux prix de la liberté d’expression d’Index on Censorship :

- la catégories arts, regroupant des artistes et des producteurs artistiques dont le travail s’érige contre la répression et célèbre l’expression artistique libre,

- la catégorie campagne, composée d’activistes et de militants ayant oeuvré de manière décisive contre la censure et pour la liberté d’expression,

- la catégorie activisme digital, qui recouvre l’utilisation innovante de toute forme de technologie destinée à contourner la censure et assurer l’indépendance et la liberté des échanges d’informations,

- la catégorie journalisme, représentant toute forme de journalisme courageux, déterminé et à grand impact s’employant à exposer la censure et son cortège de menaces à la liberté d’expression.

Les nominés dont le profil s’y prête sont également en liste pour l’attribution de la bourse Musique en exil, qui soutient les musiciens et leurs œuvres quand ils sont menacés.

Tous ceux ayant remporté un prix se voient offrir une semaine de résidence à Londres (avril 2017) pendant laquelle ils reçoivent des conseils en formation, en création de réseaux et en gestion. S’y ajoutent ensuite 12 mois d’aide et d’accompagnement leur garantissant la possibilité de perpétrer et étendre leur précieux travail de défense de la libre expression à travers le monde.

« Non seulement l’attribution des prix de la liberté d’expression assure une visibilité aux personnes et aux groupes dont le travail brillant et valeureux n’a de cesse de promouvoir la liberté d’expression à l’échelle internationale, mais cela consolide également leurs structures et leur organisation », dit Jodie Ginsbberg, PDG de Index. « Ces gens sont de véritables héros. Des gens qui, souvent, doivent faire face à de considérables obstacles et à un danger immense et bien réel, dans le simple but de faire valoir leur libre expression. J’incite vivement tout un chacun à nous soumettre le nom de leur champion de la libre expression, il faut s’assurer que leur voix soit entendue. »

La liste des prétendants aux prix 2017 sera annoncée fin janvier. Les noms des gagnants seront révélés lors d’une cérémonie de gala le 19 avril 2017 à Londres au Unicorn Theatre.

Pour plus d’informations quant aux prix et à la bourse, veuillez contacter [email protected] ou appeler le +44 (0)207 963 7262.

Also available in: Arabic, English, German, Italian, Mandarin, Portuguese (Brazil), Portuguese (Portugal), Russian, Spanish, Turkish

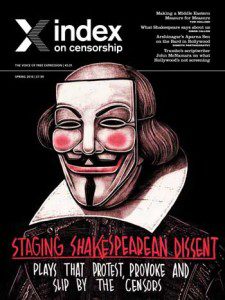

22 Apr 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016 Extras

Order your copy of the spring issue of Index on Censorship here.

Saturday 23 April marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. The Bard’s work has long been used to tackle difficult or controversial issues; issues that most often only received an audience due to the cloak of his respectability. To honour the occasion Index has put together a list of all things Shakespeare.

Shakespeare and his role in protest and dissent is the theme of the spring 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine: Staging Shakespearean Dissent; Plays That Protest, Provoke and Slip by the Censors. The issue features pieces that explore how the bard’s plays have been used to circumvent censorship and tackle difficult issues around the world; from Bollywood adaptions to Othello in apartheid-era South Africa and a ground-breaking recent performance of Romeo and Juliet between Kosovan and Serbian theatres, along with reports on theatre upsetting people in the USA, and interviews with directors around the world

Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley introduces our Shakespeare special issue with her editorial piece, How Shakespeare’s plays smuggle protest. In this piece Jolley discusses how the work of “established” or “historic” playwrights gave actors the chance to tackle themes that would otherwise never be allowed.

Shakespeare was no stranger to censorship, from the Elizabethan to Jacobean police states. In this extract actor and theatre director Simon Callow looks at how his plays amused monarchs and dictators but also prompted their anger.

My Mate Shakespeare recasts the playwright as a brandy loving bingo addict, struggling in a war zone. The poem, which was published in the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, was written by poet Edin Suljic following a visit to his home country, Former Yugoslavia. The issue also features an interview with the poet, who fled to London in 1991 ahead of the country’s impending war, discussing his inspiration for the poem and his involvement with theatre group Bards Without Borders.

How well do you know Shakespeare? Take our quiz and see how much you know about the Bard and his work.

The theatre and censorship reading list is a compilation of articles from the magazine archive covering theatre censorship across the world. From the censorship of Romeo and Juliet in US high school textbooks to Janet Suzman’s controversial production of Othello in apartheid-era South Africa, to the banning of performances of Macbeth in actors’ homes in Czechoslovakia.

In an interview with magazine editor Rachael Jolley an award-winning cartoonist, Ben Jennings, discusses his design for the latest Index on Censorship magazine cover on the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death.

Hitler was a Shakespeare fan; Stalin feared Hamlet; Othello broke ground in apartheid-era South Africa; and Brazil’s current political crisis can be reflected by Julius Caesar. Across the world different Shakespearean plays have different significance and power. In our global guide to using Shakespeare to battle power some of our writers talk about some of the most controversial performances and their consequences.

Order your full-colour print copy of our Shakespeare magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.

11 Apr 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016 Extras

Kemel Aydogan’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Turkey. Credit: Mehmet Çakici

Hitler was a Shakespeare fan; Stalin feared Hamlet; Othello broke ground in apartheid-era South Africa; and Brazil’s current political crisis can be reflected by Julius Caesar. Across the world different Shakespearean plays have different significance and power. The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, a Shakespeare special to mark the 400th anniversary of his death, takes a global look at the playwright’s influence, explores how censors have dealt with his works and also how performances have been used to tackle subjects that might otherwise have been off limits. Below some of our writers talk about some of the most controversial performances and their consequences.

(For the more on the rest of the magazine, see full contents and subscription details here.)

Kaya Genç on A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream in Turkey

“When Turkish poet Can Yücel translated A Midsummer’s Night Dream, he saw the potential to reflect Turkey’s authoritarian climate in a way that would pass under the radar of the military intelligence’s hardworking censors. Like lovers in Shakespeare’s comedy who are tricked by fairies into falling in love with characters they actually dislike, his adaptation [which was staged in 1981 and led to the arrests of many of the actors] drew on the idea that Turkey’s people were forced by the state to love the authority figures that oppressed them the most. They were subjugated by the military patriarchy, the same way the play’s female and artisan characters were subjugated by Athenian patriarchy.

Kemal Aydoğan, the director of the latest Turkish adaptation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, described the work as ‘one of the most political plays ever written’. For Aydoğan, the scene in which the Amazonian queen Hippolyta is subjugated and taken hostage by the Theseus marks a turning point in the play. ‘That Hermia is not allowed to marry the man she loves but has to wed the man assigned to her by her father is another sign of women’s subjugation by men,’ he said. This, according to Aydoğan, is sadly familiar terrain for Turkey where women are frequently told by male politicians to know their place, keep silent and do as they are told.’ ”

Claire Rigby on Julius Caesar in Brazil

“In a Brazil seething with political intrigue, in which the impeachment proceedings currently facing President Dilma Rousseff are just the most visible tip of a profound turbulence which has gripped the country since her re-election in October 2014, director Roberto Alvim’s 2015 adaptation of Julius Caesar was inspired by a televised presidential debate he saw in the final days of the election campaign, in which centre-left Rousseff faced off against her centre-right opponent Aécio Neves. ‘I watched the debate as it became utterly polarised between Dilma and Aécio, and the famous clash between Mark Antony and Brutus instantly came to mind,’ he said. ‘It was the idea that the same facts can be drawn in such completely different ways by the power of speech: the power of the word to reframe the facts, and its central importance in the political game.’ ”

György Spiró on Richard III in Hungary

“Richard III was staged in Kaposvár, which had Hungary’s very best theatre at the time. This was 1982.

Charges were brought against the production, because the Earl of Richmond wore dark glasses. A few weeks earlier, on 13 December 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski declared a state of emergency in Poland. For health reasons he wore sunglasses every time he appeared in public.”

Simon Callow on Hamlet under Stalin and the Nazis

“In 1941, Joseph Stalin banned Hamlet. The historian Arthur Mendel wrote: ‘The very idea of showing on the stage a thoughtful, reflective hero who took nothing on faith, who intently scrutinized the life around him in an effort to discover for himself, without outside ‘prompting,’ the reasons for its defects, separating truth from falsehood, the very idea seemed almost ‘criminal’.’ Having Hamlet suppressed must have been a nasty shock for Russians: at least since the times of novelist and short story writer Ivan Turgenev, the Danish Prince had been identified with the Russian soul. Ten years earlier, Adolf Hitler had claimed the play as quintessentially Aryan, and described Nazi Germany as resembling Elizabethan England, in its youthfulness and vitality (unlike the allegedly decadent and moribund British Empire). In his Germany, Hamlet was reimagined as a proto-German warrior. Only weeks after Hitler took power in 1933 an official party publication appeared titled Shakespeare – A Germanic Writer.”

Natasha Joseph on Othello in South Africa

“In 1987, actress and director Janet Suzman decided to stage Othello in her native South Africa, bringing ‘the moor of Venice’ to life at Johannesburg’s iconic Market Theatre. It was just two years since Prime Minister PW Botha had repealed one of apartheid’s most reviled laws, the Immorality Act, which banned sexual relationships between people of different races. Even without the legislation, many white South Africans baulked at the idea of interracial desire. No wonder, then, that Suzman’s production attracted what she has described as ‘millions of bags full of hate letters from people who thought that this was an outrage’.

But in a country famous for sweeping censorship and restrictions on freedom of movement, speech and association, the play was not banned. Why? Because the apartheid government ‘would have been the laughing stock of the world if they had banned Shakespeare’, Suzman told Index on Censorship. ‘Any government would be really embarrassed to ban Shakespeare. The apartheid government was frightened of ridicule. Everyone is frightened of laughter.’ ”

For more articles on Shakespeare’s battle with power around the world, see our latest magazine. Order your copy here, or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year, with a free trial). Copies are also available in excellent bookshops including at the BFI, Mag Culture and Serpentine Gallery (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester) and on Amazon or a digital magazine on exacteditions.com. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.