9 Jan 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Los guerreros islamistas de Al Shabab controlan una quinta parte de Somalia y tienen su propia emisora de radio. Ismail Einashe habla con los periodistas que arriesgan su vida retransmitiendo noticias sobre las actividades del grupo terrorista”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Un periodista retransmite desde Radio Shabelle, una de las populares emisoras de Mogadiscio (Somalia), que corren peligro por pronunciarse contra la organización terrorista Al Shabab, Amisom Public Information/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Cada mañana, antes de ir a trabajar en Radio Kulmiye, en el centro de Mogadiscio, Maruan Mayu Huseín tiene que comprobar que no haya bombas en su coche. «Miro debajo de las ruedas, pero normalmente ponen las bombas debajo del asiento», dice. «Si me paro en algún lado de la ciudad, entonces tengo que volver a mirar, porque a veces me sigue gente».

Los periodistas somalíes como Huseín viven bajo la amenaza constante del poderoso grupo islamista Al Shabab, estrechamente relacionado con Al Qaeda. Para el grupo, colocar una bomba debajo del asiento de un coche y detonarla a distancia es marca de la casa a la hora de matar a periodistas somalíes. Huseín lo confirma: «Conozco gente muerta y herida por culpa de las bombas que les habían colocado en el coche».

Periodistas como Hindia Hayi Mohamed, madre de cinco hijos, han sido víctimas de esta táctica de Al Shabab. Trabajaba para Radio Mogadiscio y la Televisión Nacional Somalí, dos medios estatales de noticias, cuando un coche bomba la mató a las puertas de la embajada turca en Mogadiscio el 3 de diciembre de 2015. Los integrantes de Al Shabab que la asesinaron habían colocado una bomba bajo el asiento de su coche. Era la viuda de Liban Ali Nur, director de los informativos de la Televisión Nacional Somalí y fallecido en la explosión de un atentado suicida de Al Shabab en septiembre de 2012, junto a otros tres periodistas, en una popular cafetería de la capital.

Los periodistas de radio como Huseín son vulnerables cuando salen de su casa, pues es fácil acribillarlos por la calle. Huseín es reportero para una popular emisora local que retransmite noticias a las partes sur y central de Somalia. Como cuenta a Index: «Si Al Shabab os ve a vosotros, no os dejan pasar. Si me ven a mí, me matan. Trabajar como periodista radiofónico en Somalia es muy duro. El problema es hoy puede haber un ataque terrorista aquí y, mañana, en cualquier otro lado».

La radio sigue siendo el principal medio de la gente para informarse y enterarse de las noticias en Somalia. Hay pocos periódicos impresos y un bajo índice de alfabetización. El somalí solo pasó a ser una lengua escrita en 1972 y, a causa de la guerra civil, no se publican muchos libros en el país. Internet es popular, pero se trata de un fenómeno en su mayoría urbano, especialmente entre los jóvenes y los que han vuelto de la diáspora. Los informativos de televisión existen, pero el acceso a televisores es limitado en uno de los países más pobres del mundo. Por todo ello, la radio sigue siendo crucial. Laura Hammond, experta en Somalia de la Facultad de Estudios Orientales y Africanos de la Universidad de Londres, explica: «La somalí es una cultura oral, y la transmisión de información a través de la radio es una extensión de la antigua tradición de la oración y el intercambio de información por medio de la poesía y la palabra hablada».

Las fuentes radiofónicas que gozan de mayor prestigio son el canal somalí de la BBC, que hace poco celebró su sexagésimo aniversario, y el servicio somalí de Voice of America. Pero al comunicar al público las noticias sobre lo que está pasando en su país, los periodistas somalíes se exponen a una violencia e impunidad de las más terribles en el continente africano. En el Índice de Libertad de Prensa de 2017 realizado por Reporteros sin Fronteras, Somalia ocupa el puesto 167 de 180.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Mohamed Ibrahim Moalimuu, el secretario general del Sindicato Nacional de Periodistas Somalíes, nos lo cuenta: «Somalia sigue siendo uno de los peores países para operar como periodista, una profesión que a menudo está en el punto de mira. Son víctimas de intimidaciones constantes, arrestos arbitrarios, tortura y, en ocasiones, asesinato».

Algunos periodistas somalíes se han visto forzados a esconderse por las amenazas continuadas que reciben de Al Shabab. Un periodista al que entrevistó Index, y que quiso permanecer anónimo por razones de seguridad, cuenta: «Mi vida está patas arriba desde que Al Shabab empezó a darme caza […] Al Shabab me llama desde números desconocidos y me dice: “Tu vida está peligro.”»

El periodista es un conocido reportero de radio que cubre noticias sobre el grupo armado. Añade: «He recibido amenazas de Al Shabab. Escucharon mis reportajes sobre sus ataques terroristas y desde entonces me han amenazado de muerte». Lleva dos años ocultándose de ellos, temiendo por su vida.

En febrero de 2017, unos operativos de Al Shabab visitaron la casa de su madre. Relata: «Fueron a casa de mi madre. Le preguntaron: “¿Dónde está?” Ella les dijo que no estaba allí y le dijeron a mi madre: “La próxima vez que veas a tu hijo, estará muerto.” Le tiembla la voz al contarlo. Hoy, exhausto de pasar los días oculto de las balas de Al Shabab, añade: «Quiero recuperar mi vida, pero soy un periodista joven que vive bajo amenaza […] No puedo dejar de ser periodista. No dejaré de usar mi voz».

Según Angela Quintal, coordinadora de programación para África en el Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas, 62 de ellos han perdido la vida en Somalia desde 1992. Más de la mitad de ellos (43 en total) fueron asesinados, con Al Shabab bajo sospecha de ser responsable de la mayoría de las muertes. Pese a que los asesinatos de periodistas han disminuido desde 2012, en 2016 mataron a tres.

Los antecedentes son que, tras el colapso del estado somalí y la guerra civil de 1991, el país se sumió en una orgía de violencia y terrorismo, a lo que se añade una sequía reciente de efectos devastadores. En el vocabulario de la política internacional, Somalia era conocida como «el estado más fallido» del mundo, pero en los últimos años ha dado paso a la expresión «estado frágil». De entre todas las amenazas a las que ha hecho frente Somalia, Al Shabab, posiblemente la organización terrorista más potente de África, se lleva la palma.

En los últimos años, Al Shabab ha perdido algunos territorios en partes del sur de Somalia, como el puerto estratégico de Kismayo, así como mucho territorio en Mogadiscio. Pero aún controla amplias franjas de territorio en el país.

Al Shabab no solo ataca a periodistas radiofónicos somalíes, sino que tiene su propia emisora, llamada Al Ándalus, desde la que retransmiten propaganda yihadista con música devocional islámica, así como estridentes informativos sobre los “kafirs”, o infieles, y cuántos de ellos han matado. La emisora cuenta con un amplio alcance en las partes meridionales de Somalia y en las áreas bajo su control, y está disponible en internet.

Moalimuu dice que Al Ándalus aún funciona y emite en áreas controladas por Al Shabab.

Mary Harper, editora de BBC África e inmersa en la escritura de un libro sobre Al Shabab, afirma que las actividades radiofónicas de la organización terrorista les lleva «siglos de ventaja a Boko Haram».

En lo que respecta a sus ataques a civiles, al gobierno o a las fuerzas de la Unión Africana, según Harper, ofrece una visión bastante fidedigna, pero tiende a exagerar el número de muertos que provoca. Utilizan Al Ándalus como instrumento para suprimir la libertad de expresión y extender su propaganda radical islamista.

Moalimuu dice: «Al Shabab prohíbe la música en todas las áreas que aún controlan. Vigilan los teléfonos móviles de los jóvenes regularmente. Los smartphones y cualquier otro tipo de móvil con cámara están prohibidos en sus territorios. Esta norma sigue aún vigente en todas las áreas controladas por Al Shabab. La gente está muy frustrada, pero no les queda otra opción que obedecer si quieren seguir con vida».

Nur Hasán, un periodista y productor audiovisual retirado de Mogadiscio, explica: « Al Shabab prohíbe la música terminantemente. Si te pillan escuchando música en las zonas bajo su control, el castigo son 40 latigazos y la humillación pública».

Harper apunta que no todas las amenazas provienen de Al Shabab: «Los periodistas de Somalia están amenazados por todas las esquinas».

Pero Huseín sigue preocupado por la amenaza del grupo terrorista. Dice que algunos periodistas de radio están tan preocupados que pasan algunas noches en el estudio en lugar de dormir en sus camas. Él, por su parte, lo tiene claro: «No me preocupará la muerte hasta que venga a por mí». Hasta entonces, dice: «Seguiré mirando que no haya bombas cuando salgo de casa, pero mi destino está en manos de Dios».

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Ismail Einashe escribe reportajes regularmente para la revista Index on Censorship desde el Cuerno de África. Nació en Somalilandia y es miembro académico del Dart Center de la Universidad de Columbia con una beca Ochberg.

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista Index on Censorship en otoño de 2017.

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Free to Air” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores how radio has been reborn and is innovating ways to deliver news in war zones, developing countries and online

With: Ismail Einashe, Peter Bazalgette, Wana Udobang[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95458″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

27 Dec 2017 | Belarus, Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine examines the state of the right of assembly 50 years on from 1968. Kyra McNaughton details how authorities in Belarus police the reporting of protests using data from Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project.”][vc_column_text]

Belarusian police detain Belarus Free Theatre’s Siarhai Kvachonok on Saturday March 25 2017 during protests against Presidential Decree No 3, which imposes a tax on unemployed people. (Photo: Tut.by)

“Europe’s last dictatorship” doesn’t tolerate dissent. The country’s constitution claims to protect freedom of the press, but many laws seem to contradict this.

Independent outlets are constrained by laws in favor of state-run media. Most frequently targeted are Belarus’s independent journalists and Belsat TV, alternatives to the heavily censored state-run Belarusian news. These targeted journalists often fall victim to Belarus’ restrictive regime for press accreditation, a system used by the government to “maintain its monopoly on information in one of the world’s most restrictive environments for media freedom”, according to a report by Index.

“An openly critical stance of the [Belsat TV] towards the authorities of Belarus results in the situation when it is not officially registered in the country and its journalists are pushed beyond the legal system through rules that neither grant them official accreditation, nor recognise freelancers as journalists”, said Andrei Aliaksandrau, deputy director of BelaPAN and editor of the Belarus Journal. “Reporters are subject to administrative prosecution, arrests and fines on ridiculous charges of ‘illegal production of mass media materials’”.

In order to stifle awareness of the public’s unhappiness with the current political climate, the government targets journalists covering protests before, during and after the demonstrations. Index’s Mapping Media Freedom has documented as many as 22 cases since 2015.

“For the past 20 years the authorities in Belarus have been known for their harsh police violence against street protests, including against journalists … After 2011 street protests and mass opposition rallies became rare in Belarus, right until early 2017 when people returned to the streets of Belarusian cities to protest against deterioration of economic situation. The police used brutal force again; and journalists were among those detained”, said Aliaksandrau.

With tactics ranging from detention to assault, Belarusian law enforcement specifically go after independent reporters in an effort to prevent the public from knowing the full extent of protests.

Before

Between March and May of 2017, MMF documented five cases of journalists detained before they were scheduled to cover protests.

Two Belsat TV journalists and one independent journalist were detained twice in one day on their way to cover protests on 18 March 2017. The journalists were first accused of a traffic violation, then later of stealing a car and robbing a bank, according to MMF. The journalists were going to cover one protest in a series nationwide called against a proposed tax.

That same day, four different groups of Belsat journalists were detained in different cities to prevent coverage of demonstrations.

Also on the same day, two Belsat TV journalists were detained during a live broadcast. They were reporting on a possible protest when two police officers arrived. The two were detained without explanation and released hours later.

During

Since 2015 there are 11 documented cases on MMF of journalists being targeted while on site of a protest.

On 25 March 2017, Freedom Day in Belarus, 39 journalists across the country were detained, totalling around 90 detentions alone in the month of March, according to the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ). MMF reports seven of the 30 detained were beaten by police.

After the mass detentions on Freedom Day, 16 journalists were detained the next day during solidarity rallies across the country. Of those detained between both days, some were charged with “hooliganism” and sentenced from five to fifteen days in prison.

In 2015, as independent blogger Viktar Nikitsenka was leaving a demonstration, plain-clothed police officers seized him and dragged him into a bus where he was reportedly beaten. Information and materials were deleted from his phone and camera and his equipment was stolen. He was fined 450 euros.

When Nikitsenka filed a complaint against the officers for unlawful use of force, it was rejected.

After

On 18 March 2017, four Belsat TV crews intending to report on protests were detained in different cities. In one incident, Belsat TV journalist Ales Lyauchuk reported that he and a colleague were stopped by traffic police after covering a protest, then “dragged out of the car [and] brutally assaulted”. The two were reportedly stopped without explanation and held at the station for three hours, their equipment damaged and seized.

“They said that if this goes on, they will shoot us”, Lyauchuk said.

Five days before, video blogger Maksim Filipovich received three separate prison sentences for participating in “illegal” protests. Riot police arrested him at his parents flat, which he livestreamed.

“Targeting journalists who are trying to report on protests is misuse of official powers and it shows how little media freedom there is in Belarus”, said Joy Hyvarinen, Head of Advocacy.

As coverage of protests is censored by targeted the journalists who cover them, freedom of expression both in the form of journalism but also protest is being stifled. Instead of immediately targeting protests, the Belarusian government diminishes the purpose of a protest, since the cause can’t gain attention.

In countries like Belarus where press freedom is protected by the constitution, rulers ignore the law to advance a political agenda.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F%20|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the summer 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores the 50th anniversary of 1968, the year the world took to the streets, to look at all aspects related to protest.

With: Micah White, Robert McCrum, Ariel Dorfman, Anuradha Roy and more.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified more than 3,700 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ element_width=”12″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1513938526925-22ecd957-f7ad-4″ taxonomies=”19962″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

9 Nov 2017 | Asia and Pacific, Awards, China, Europe and Central Asia, Fellowship, Fellowship 2017, Maldives, News and features, Russia, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

From left: Cartoonist Martin Rowson accepting the Arts Award on behalf of Chinese cartoonist Rebel Pepper; Alp Toker of Digital Activism Award-winner Turkey Blocks; Isik Mater of Digital Activism Award-winner Turkey Blocks; Anastasia Zotova, wife and campaign partner of Campaigning Award-winner Ildar Dadin; Ahmed Naish, deputy editor of Journalism Award-winning Maldives Independent; Zaheena Rasheed, former editor of Journalism Award-winning Maldives Independent. (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Since the Index on Censorship Awards, the 2017 fellows have been busy doing important work in their respective fields to further their cause and for stronger freedom of expression around the world.

Rebel Pepper / Arts

Baby Pepper

Rebel Pepper, the Chinese cartoonist critical of the country’s government, now lives in exile in the USA where he works for Radio Free Asia. “Everything is going well, and I have a lot of friendly colleagues who like my work,” he told Index on Censorship.

He also continues to write his column in the Japanese version of Newsweek and worries about many recent developments in his home country. “The CCP’s control of society is becoming more and more severe, people are exposed to less and less real news from the outside world, and vice versa,” he says. “It’s hard to sum up because there are so many problems right now.”

The artist is still getting cartoons published and says the Index on Censorship award gave him the energy to “keep walking on the creative road”.

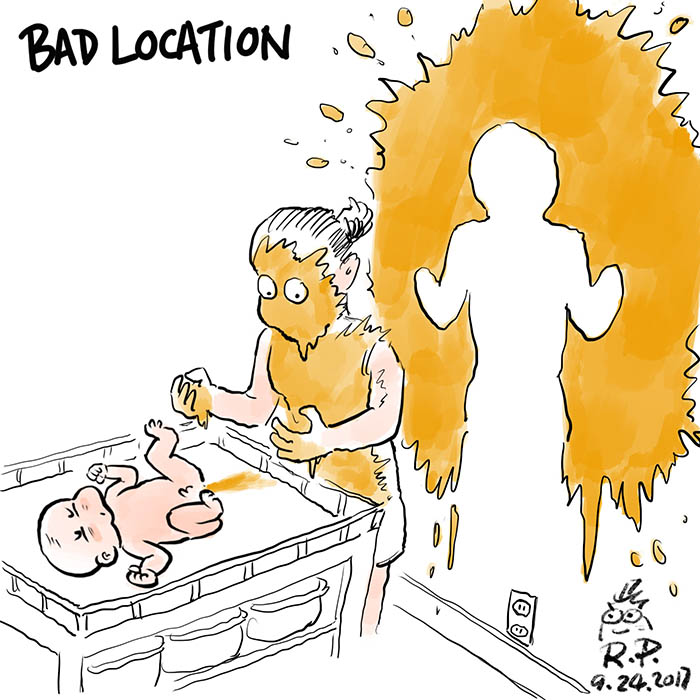

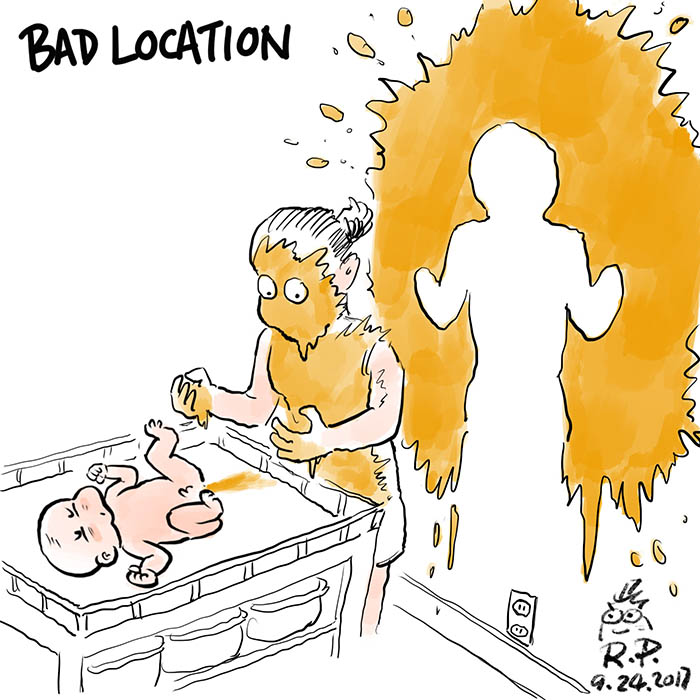

There is a new addition to the Rebel Pepper family, with baby Kitano. “Every day I have to change a lot of diapers, which has had a big influence on my sleeping patterns, so I have to find some fun from him,” Rebel Pepper tells Index, brandishing a cartoon to illustrate his point.

Idler Dadin / Campaigning

Campaigning fellow Ildar Dadin has returned to activism since his release from prison in February. “Along with friends or on single pickets, we are openly showing that we aren’t in agreement with what’s happening in the country,” Dadin tells Index.

Last month he was detained in St Petersburg while trying to film a woman being assaulted by police. “The situation in this country now is really bad,” Dadin says. “There’s a new kind of police force which can attack and humiliate people, which is very serious.”

He describes the arrests of more than 260 people during anti-Putin protests across Russia — including St Petersburg — in October as “pretty much normal for any activist in the country”.

Dadin believes that pressure from civil society both in Russia and abroad were partially responsible for his release. He hopes for “justice for all people, not just Russians”.

Moving forward, Index is helping Dadin with his transition to life outside of prison and prioritising his health and also helping him to gain additional international exposure.

Turkey Blocks / Digital Activism

“We are now going to be the NetBlocks project and expand our work,” director of research at Turkey Blocks Isik Mater tells Index. The team are taking steps to formalise some of their tools and methodologies, expand into new regions that have similar needs and now cover several countries experimentally.

The Turkey Blocks team have also developed a new tool called Cost, which calculates the financial impact of mass-censorship. “Governments don’t tend to care about the human rights argument, so they don’t listen to it,” says Alp Toker, founder of Turkey Blocks. “But if you tell them ‘this will cost x million dollars of harm to GDP’ then they perk up because that can become a political issue, which is a very powerful method of convincing governments not to censor content.”

Turkey, however, has been quite quiet recently in terms of internet shutdowns, after a barrage of such incidents in the year following the attempted coup in July 2016. In fact, the Turkish government have been using Turkey Blocks data on internet shutdowns as a kind of audit, Toker explains. “We ran our first panel with the Turkish government just a few weeks ago, which is kind of historic,” he says. “We are seeing really positive things, and although they have a long way to go it should be noted that they’ve been willing to have a dialogue with civil society and with a human rights group.”

Index on Censorship is helping Turkey Blocks through the process of forming a board and incorporating public speaking training skills for Mater so that she too can begin to make more public appearances.

Maldives Independent / Journalism

Staff at the Maldives Independent taking part in self-defence training.

Journalism fellows at Maldives Independent are going through a period of change. Former editor Zaheena Rasheed left the publication soon after awards week in London to take up a position on the online team at Al Jazeera, where she has recently been doing a lot of work covering the Rohingya refugee crisis from Bangladesh.

For personal reasons, Rasheed finds it difficult to be involved with the Maldives on top of this. “A friend of ours in the Maldives, Yameen Rasheed, was murdered at the end of the Index awards week in London and that was a big blow — it was very hard for me.”

Yameen Rasheed was a prominent blogger and internet activist who died from multiple stab wounds after an attack in the stairway of his apartment building in Malé on Sunday 23 April 2017. Index on Censorship has been involved in helping the Maldives Independent better secure their personal and office safety since Yameen Rasheed’s murder, including a recent self-defence training session.

A new editor took over at the Maldives Independent in mid-September and since then the publication has seen a noticeable spike in readership, and reporters are encouraged to get out and meet people, build relationships and contacts.

“It’s fairly calm at the moment — there have been no coups, for example — so I see this period as a time to hone the team’s reporting and feature writing skills,” a staff member tells Index. “We’re doing a broad mix of news and features: politics, tourism, mental health, rave culture, the hipster coffee scene, rural development, sex abuse cover-ups.”

Staff at the Maldives Independent hope that the publication continues to be a forum for debate and free speech, that it holds power to account, exposes wrongdoing and corruption and most of all give insight into a country that many people have only one image of.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1510228913303-fd0d57c2-b760-1″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]