Katsyaryna Andreeva

LETTERS FROM LUKASHENKA'S PRISONERS Katsyaryna Andreeva Journalist Detained on 15 November 2020 "I do not feel anger, resentment, or a desire for revenge towards those who made the decision to do this to me. What do I feel? Pity for them following orders." READER'S...Banning books is a weak act

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

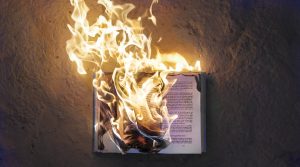

Book burning, photo: Fred Kearney

It seems surreal that in the 21st century in Europe and in the US, we still have to make the argument for a free press and public access to literature. But since 1982 an international coalition against censorship has had to make exactly that case.

I find the concept of banned books chilling. Why would you seek to ban or destroy literature, culture and history? Why would you seek to remove arguments you disagree with rather than challenge them and prove that you are right? Banning books is a weak act – done by those who know that their arguments are easily defeated. But is this level of control and repression which scares me – we know where it can lead.

Of all the touching and heart-breaking Holocaust memorials in Berlin, it is the Empty Library that made me stop – a visual representation of what book burning is and what happens when intolerance is allowed to dominate. On 10 May 1933 20,000 books were burned – their authors were Jews, Communists and Socialists – 40,000 people crowded the Bebelplatz to watch them burn.

This is where banning books can lead. This is the ultimate reality of censorship and intolerance.

Occasionally I am asked why free speech is so important to me. Why is this even important anymore in the age of the internet and nearly unfettered access to the accumulated knowledge of the world for those of us lucky enough to live in liberal democracies. But this is why I fight for free expression, for tolerance, for knowledge, for debate. This is why I work at Index on Censorship. I don’t have to agree with an author to defend their right to publish. I don’t have to like a book to defend its right to be in a library and I don’t have to delete works that I fundamentally oppose.

Which brings us to Banned Book Week. Every year, in fact nearly every day, there are reports of libraries removing books or authors being challenged – not necessarily for their published works but on occasion for their views. The American Library Association publishes an annual list of the most challenged books in the US:

- George by Alex Gino. Challenged, banned, and restricted for LGBTQIA+ content, conflicting with a religious viewpoint, and not reflecting “the values of our community”.

- Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You by Ibram X. Kendi and Jason Reynolds. Banned and challenged because of the author’s public statements and because of claims that the book contains “selective storytelling incidents” and does not encompass racism against all people.

- All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. Banned and challenged for profanity, drug use, and alcoholism and because it was thought to promote antipolice views, contain divisive topics, and be “too much of a sensitive matter right now”.

- Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson. Banned, challenged, and restricted because it was thought to contain a political viewpoint, it was claimed to be biased against male students, and it included rape and profanity.

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie. Banned and challenged for profanity, sexual references, and allegations of sexual misconduct on the part of the author.

- Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story about Racial Injustice by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard, illustrated by Jennifer Zivoin. Challenged for “divisive language” and because it was thought to promote antipolice views.

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee. Banned and challenged for racial slurs and their negative effect on students, featuring a “white saviour” character, and its perception of the Black experience.

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck. Banned and challenged for racial slurs and racist stereotypes and their negative effect on students.

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. Banned and challenged because it was considered sexually explicit and depicts child sexual abuse.

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas. Challenged for profanity, and because it was thought to promote an antipolice message.

These are not the only banned works we know of but it gives us all a flavour of the debate that is occurring across our liberal democracies and makes it clear of the work we still have to do. Of course, it isn’t just literature that is challenged or banned – but poetry and arts continue to be censored. Which is why, in partnership with the British Library. we held an event to mark Banned Books Week exploring poetry and protest – with Dr Choman Hardi and ko ko thett, chaired by Index on Censorship’s vice chair Kate Maltby. You can watch the event on catch-up here.

So, as we collective mark Banned Books week – I urge you – go into a bookshop or a library and get a book that challenges you, that inspires you and one that others seek to ban![/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”41669″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Banned Books Week 2021: Poetry in Protest

[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”117512″ img_size=”full”][vc_column_text]

Marking Banned Books Week 2021, Index on Censorship and the British Library present a conversation with poets at the frontlines of protest movements fighting for the right to speak freely and without fear of persecution.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Poetry is frequently used as a tool in protest movements to inspire, unite, and mobilise support. From Black Lives Matter and women’s liberation to protest movements in Myanmar and Afghanistan, poetry holds the power to gather crowds during a rally, or grab attention online. Poets can offer support and guidance in the most challenging, tragic or dangerous situations. Join Myanmarese-British poet ko ko thett and poet and scholar Dr Choman Hardi for a live poetry reading and conversation about the power of poetry in protest movements. The event will be chaired by Index on Censorship deputy chair Kate Maltby.

Marking Banned Books Week 2021, which has the theme “Books Unite Us. Censorship Divides Us”, Index on Censorship and the British Library invite you to explore the role of poetry in protest. What role does poetry play in protest movements? And can poetry be a form of protest in its own right?

Kate Maltby is the Deputy Chair of the Index on Censorship Board of Trustees. She is a critic, columnist, and scholar. She is currently working towards the completion of a PhD which examines the intellectual life of Elizabeth I, through the prism of her accomplished translations of Latin poetry, her own poems and recently attributed letters, and her representation as a learned queen by writers such as Shakespeare, Spenser and Sidney.

ko ko thett started publishing poems in samizdat format at Yangon Institute of Technology in the early 1990s. After a brush with the authorities in the December 1996 protests, he left Burma, led an itinerant life in Asia, Europe and North America and moved back to Myanmar in 2017. He has published several collections of poems and translations in Burmese and English. His poems have been translated into a dozen languages and are widely anthologised. He now lives in Norwich, UK.

Dr Choman Hardi is an educator, poet, and scholar known for pioneering work on issues of gender and education in the Kurdistan region of Iraq and beyond. After 26 years of exile, she returned home in 2014 to teach English and initiate gender studies at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani (AUIS), where she also served as English department chair in 2015-16. She is the author of critically acclaimed books in the fields of poetry, academia, and translation. Since 2010, poems from her first English collection, Life for Us (Bloodaxe, 2004) have been studied by secondary school students in the UK as part of their English curriculum. Her second collection, Considering the Women (Bloodaxe, 2015), was given a Recommendation by the Poetry Book Society and shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection. Her translation of Sherko Bekas’ Butterfly Valley (ARC, 2018) won a PEN Translates Award.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]When: Wednesday 29 September 2021, 18.30-19.30

Where: ONLINE

Tickets: Free, advance booking essential[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]