Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Rashid Razaq is a reporter for London Evening Standard and a playwright.

What is the solution to the Muslim Problem? Britain has tried multiculturalism; the French, a stricter enforcement of secularism. Neither has been an unequivocal success.

I’m afraid I don’t have the answer. I have only doubts and questions, whereas the terrorists have certainties and guns.

The only thing I can say with a fair amount of confidence is that the right not to be offended is a ridiculous thing. For there is no way to measure a subjective, emotional state other than to ask “Does this offend you?” in the same way you would ask “Are you tired?”, “Are you hungry?”, “Do you love me?”

One person’s silly cartoon is another person’s existential threat. Try as I might, I cannot get offended by a drawing. Maybe I’m a bad Muslim, maybe a true believer would be so mortally wounded by an image, any image, of the Prophet Mohammed that the only remedy is bloodshed. But I don’t think that’s the case. Much of the outrage is manufactured, stoked up by rabble-rousers for political purposes. Because that’s the brilliance of the right not to be offended (Irony — just to be crystal- clear): you can get offended on other people’s behalf, you can get offended about books you haven’t read, about things that may or may not exist.

Loath as I am to bring up scripture in a discussion about religion, the Islamic prohibition against making graven images of the Prophet Mohammed only really applies to Muslims. It stems from the same commandment not to worship false idols, intended to protect against idolatry.

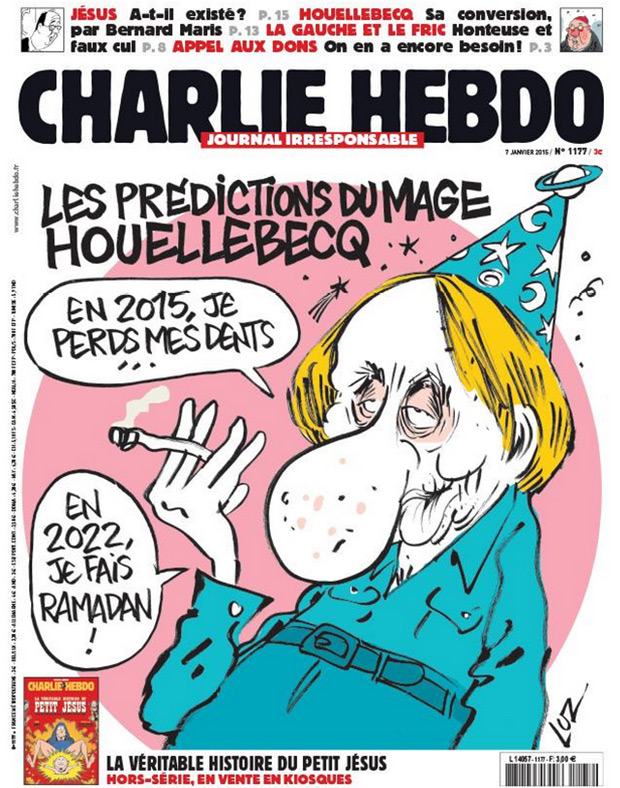

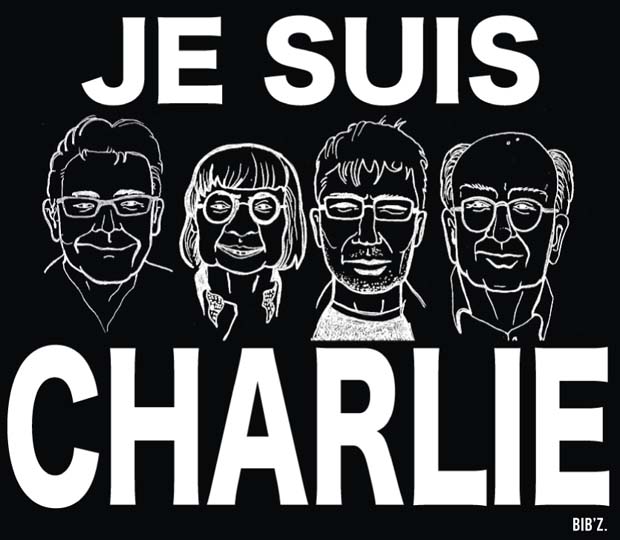

As far as I’m aware neither Stephane Charbonnier nor any of his leading cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo was a practising Muslim. The two victims believed to be Muslims, copy-editor Mustapha Ourad and policeman Ahmed Merabet, appear to have been collateral damage rather than targets.

So, just to make the murders even more pointless, you have Muslims killing non-Muslims for not sufficiently respecting something which they don’t believe in. Irony? I’m not sure.

Not that there is any justification. It is a shabby excuse for a heinous act, convenient religious cover for something that is probably nothing more than a twisted marketing stunt for al Qaeda in Yemen, if initial accounts prove to be true. The killings were not carried out to “avenge” the Prophet’s honour. Their real intent was to remind the West: “We’re still here”.

Many lofty and true words will be written about the need to protect the freedom of expression. But the attack on Charlie Hebdo wasn’t an attack on freedom of expression. It was an attack on an easy target. A group of middle-aged, unarmed cartoonists were never going to be much of a match for battle-hardened jihadists brandishing Kalashnikovs.

Satire is scary for people who can’t live with doubt. Because satire is all about creating doubt, questioning the way things are done, challenging those in power, pushing for change. I don’t know if the killings say more about the power of satire or the weakness of the gunmen’s supposed faith.

The jihadists want us to accept their narrative, that they are brave holy warriors and not just some over-sensitive, bloodthirsty bullies. But I have my doubts. I think the terrorists continue to provoke fear because they’re afraid. Afraid that we’ll realise their brand of religion is a joke.

Nadhim Zahawi is a member of the BIS Select Committee, the Party’s Policy Board and MP for Stratford on Avon. This article is from Conservative Home

You can’t kill an idea by killing people. The sickening attack on Charlie Hebdo has shown that to be true. As France mourns her dead, millions around the world are discovering the work of her bravest satirists. Nous sommes Charlie.

Unfortunately, the same is true of the terrorists. Bin Laden may be at the bottom of the sea, but his poisonous ideology lives on. As long as it inspires deluded young men to kill, these attacks will keep happening. We can’t win this fight unless we also win the battle of ideas.

This is an urgent task. Thousands of EU citizens have travelled to the Middle East to serve under ISIS’s black banner. Many will return with combat experience and carrying the virus of radicalism. Some will be eager to put their new terrorist skills to work. It’s vital that we stop them.

Our security services have an important role to play, but research suggests that the most effective way of tackling terrorism is “changing the narrative”. That means challenging the stories used by extremists to justify their twisted worldview.

First and foremost, this means rejecting the idea that this this is a clash of civilizations: Islam versus the West. The reality is that jihadists have claimed more lives in the Islamic world than anywhere else. In December last year, the Pakistani Taliban gunned down 132 schoolchildren in their classrooms. On the same day as the attack in Paris, a car bomb exploded in Yemen killing at least 38 people. Muslim-majority countries, as much as the West, have a clear interest in stamping out this ideology.

It’s time the Islamic world took a leadership position on this issue. When the news from Paris broke, countries such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Afghanistan were quick to condemn the attacks. Yet all three have legal systems carrying the death penalty for blasphemy. In virtually every Muslim-majority country, publishing a magazine like Charlie Hebdo would earn you a fine or imprisonment.

These laws support the idea that religious offence is a crime to be punished rather than a price we must pay for freedom of expression. They also fuel extremist violence. In Pakistan, blasphemy charges are often levied at religious minorities on the flimsiest of pretexts. Those accused are sometimes lynched by vigilante mobs while awaiting trial. Politicians who’ve dared to speak out against the laws have been assassinated.

One of the best tributes we could pay to the brave men and women of Charlie Hebdo would be to use our diplomatic influence to get some of these laws repealed. Change won’t happen overnight, and we will have to be patient with these countries. After all, the last successful prosecution for blasphemy in Britain was as recent as 1977, and the laws only came off the statute books in 2008.

I am not arguing that we should preach to Islamic governments; but nor should we turn a blind eye to this issue. Reforming attitudes to blasphemy would send a powerful message to extremists: freedom of speech isn’t just a Western value – it’s our common birthright as human beings.

And we shouldn’t be frightened of having a conversation about religion here at home. Talking about religion doesn’t come naturally. As a culture, we ‘don’t do God’. Yet it’s vital that mainstream Muslims feel comfortable discussing their faith in public. They, not the Government, are best placed to take on the dodgy imams and self-appointed sheikhs in open debate.

The Qur’an is clear that it’s the role of Allah, not man to judge unbelievers. In the 7th Century, Ali bin Abi Talib, the cousin of the Prophet and a leader of the original Islamic Caliphate, said: “Whoever does not accept others’ opinions will perish”. There’s a sound Islamic case for freedom of expression, and it needs a good airing.

Last, we have to practice what we preach. If we want Muslims to come out and say “not in my name” every time there’s a terrorist atrocity we too need to be vocal in our condemnation of attacks on Muslims and mosques in the West.

Charlie Hebdo was a target because humour is dangerous. You can’t be the all-powerful Islamic Caliphate and be the butt of someone else’s joke. The goal of terrorism is to frighten us – so laughter is one of our most powerful weapons.

The undersigned 40 organisations call on the international community to publicly condemn the ongoing crackdown on human rights defenders, who face harassment, imprisonment, and forced exile for peacefully exercising their internationally recognised rights to freedom of expression and assembly. With parliamentary elections in Bahrain scheduled for 22 November, the international community must impress upon the government of Bahrain the importance of releasing peaceful human rights defenders as a precursor for free and fair elections.

Attacks against human rights defenders and free expression by the Bahraini government have not only increased in frequency and severity, but have enjoyed public support from the ruling elite. On 3 September 2014, King Hamad bin Isa Al-Khalifa said he will fight “wrongful use” of social media by legal means. He indicated that “there are those who attempt to exploit social media networks to publish negative thoughts, and to cause breakdown in society, under the pretext of freedom of expression or human rights.” Prior to that, the Prime Minister warned that social media users would be targeted.

The Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR) documented 16 cases where individuals were imprisoned in 2014 for statements posted on social media platforms, particularly on Twitter and Instagram. In October alone, some of Bahrain’s most prominent human rights defenders, including Nabeel Rajab, Zainab Al-Khawaja and Ghada Jamsheer, face sentencing on criminal charges related to free expression that carry years-long imprisonment.

Nabeel Rajab, President of the BCHR, Director of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights (GCHR), and Deputy Secretary General of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), was arrested on 1 October 2014 and charged with insulting the Ministry of Interior and the Bahrain Defence Forces on Twitter. Rajab was arrested the day after he returned from an advocacy tour in Europe, where he spoke about human rights abuses in Bahrain at the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, addressed the European Parliament in Brussels, and visited foreign ministries throughout Europe.

On 19 October, the Lower Criminal Court postponed ruling on Rajab’s case until 29 October and denied bail. Rajab’s family was banned from attending the proceedings. Under Article 216 of the Bahraini Penal Code, Rajab could face up to three years in prison. We believe that Rajab’s detention and criminal case are in reprisal for his international advocacy and that the Bahraini authorities are abusing the judicial system to silence Rajab. More than 100 civil society organisations have called for Rajab’s immediate and unconditional release, while the United Nations called his detention “chilling” and argued that it sends a “disturbing message.” The United States and Norway called for the government to drop the charges against Rajab, and France called on Bahrain to respect freedom of expression and facilitate free public debate.

Zainab Al-Khawaja, who is over eight months pregnant, remains in detention since 14 October on charges of insulting the King. These charges relate to two incidents, one in 2012 and another during a court appearance earlier this month, where she tore a photo of the King. On 21 October, the Court adjourned her case until 30 October and continued her detention.

Zainab Al-Khawaja is the daughter of prominent human rights defender Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, who is currently serving a life sentence in prison, following a grossly unfair trial, for calling for political reforms in Bahrain. Zainab Al-Khawaja has been subjected to continuous judicial harassment, imprisoned for most of last year and prosecuted on many occasions. Three additional trumped up charges were brought against her when she attempted to visit her father at Jaw Prison in August 2014 when he was on hunger strike. The charges are related to “entering a restricted area”, “not cooperating with police orders” and “verbal assault”.

Zainab’s sister, Maryam Al-Khawaja, was also targeted by the Bahraini government recently. The Co-Director of the GCHR is due in court on 5 November 2014 to face sentencing for allegedly “assaulting a police officer.” While the only sign that the police officer was assaulted is a scratched finger, Maryam Al-Khawaja suffered a torn shoulder muscle as a result of rough treatment at the hands of police. She spent more than two weeks in prison in September following her return to Bahrain to visit her ailing father. More than 150 civil society organisations and individuals called for Maryam Al-Khawaja’s release in September, as did UN Special Rapporteurs and Denmark.

Other human rights defenders recently jailed include feminist activist and women’s rights defender Ghada Jamsheer, detained since 15 September 2014 for comments she allegedly made on Twitter regarding corruption at Hamad University Hospital. Jamsheer faced the Lower Criminal Court on 22 October 2014 on charges of “insult and defamation over social media” in three cases and a verdict is scheduled on 29 October 2014.

While the government of Bahrain continues to publicly tout efforts towards reform, the facts on the ground speak to the contrary. Human rights defenders remain targets of government oppression, while freedom of expression and assembly are increasingly under attack. Without the immediate and unconditional release of political prisoners and human rights defenders, reform cannot become a reality in Bahrain.

We urge the international community, particularly Bahrain’s allies, to apply pressure on the government of Bahrain to end the judicial harassment of all human rights defenders. The government of Bahrain must immediately drop all charges against and ensure the release of human rights defenders and political prisoners, including Nabeel Rajab, Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja, Zainab Al-Khawaja, Ghada Jamsheer, Naji Fateel, Dr. Abduljalil Al-Singace, Nader Abdul Emam and all those detained for expressing their right to freedom of expression and assembly peacefully.

Signed,

Activist Organization for Development and Human Rights, Yemen

African Life Center

Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB)

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (ANHRI)

Avocats Sans Frontières Network

Bahrain Center for Human Rights (BCHR)

Bahrain Human Rights Observatory (BHRO)

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD)

Bahrain Salam for Human Rights

Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights (BYSHR)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

English PEN

European-Bahraini Organisation for Human Rights (EBOHR)

Freedom House

Gulf Center for Human Rights (GCHR)

Index on Censorship

International Centre for Supporting Rights and Freedom, Egypt

International Independent Commission for Human Rights, Palestine

International Awareness Youth Club, Egypt

Kuwait Institute for Human Rights

Kuwait Human Rights Society

Lawyer’s Rights Watch Canada (LWRC)

Maharat Foundation

Nidal Altaghyeer, Yemen

No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ – Italy)

Nonviolent Radical Party, Transnational and Transparty (NRPTT – Italy)

PEN International

Redress

Reporters Without Borders

Reprieve

Réseau des avocats algérien pour défendre les droits de l’homme, Algeria

Solidaritas Perempuan (SP-Women’s Solidarity for Human Rights), Indonesia

Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa (SIHA)

Syrian Non-Violent Movement

The Voice of Women

Think Young Women

Women Living Under Muslim laws, UK

Youth for Humanity, Egypt

An Egyptian man takes a photo of a large anti-Morsi protest in Tahrir Square, Egypt (Photo: Phil Gribbon/Alamy)

Imagine this: a journalist with her own news drone camera that can be sent to any coordinates in the world to film what is going on. Imagine a world where you had the ability to programme a whole set of drone cameras to go and film a riot, a rally or a refugee camp.

Imagine being able to set off your smartphone down a dangerous river, encased in a plastic bottle, to take photos that might prove the water is carrying disease or is not safe to drink. How about drone cameras that you can leash to your GPS co-ordinates to follow and film you or someone else? Those worlds should not be hard to imagine as they exist already, and, in some cases, those facilities are already being used by journalists.

The future of journalism is going to build on technologies we already have. But we must remember it isn’t really about the technology, but about what it can help us deliver. When the subject of the future of journalism is discussed it often turns to whizzy gadgets but the debate about whether the public ends up being better informed and better equipped happens less often.

The information superhighway, as the internet was once called, was supposed to give individuals amazing access to knowledge that they couldn’t access before, from historical documents to live video footage. And it has.

But the thing that most of us didn’t bargain for was that it would mean we had so much stuff coming at us. We no longer knew where to turn, our eyes and ears were full, a welter of “news” snippets became impossible to absorb, and as for analysis, well, who had time for that?

The reality of exciting new technology is that it is coming to the market at a time when the public appears to value journalists less, and can turn to Twitter or Facebook or citizen journalists to find out what’s going on in the world. Journalists; who needs them when we can find out so much for ourselves? It’s a reasonable question, and of course good and determined researchers can find out plenty of information for themselves, if they have hours to spend. But then again journalists have a whole set of tools and training that should mean they are better than the average member of the public at finding out facts and analysing reports as well as presenting the end results.

Journalists are trained and practiced at interviewing, asking the right questions and drawing out relevant pieces of information. These are rarely acknowledged skills but you have only to switch on a phone-in programme or watch a set of parliamentarians try to quiz a witness at a committee to know asking a good question is not as easy as it might seem. Knowing where to look for evidence and sources is not always so simple as putting any old question into Google either. Then there is analysing charts, graphs and tables; this should be a particularly valued set of skills. When it comes to recognising a story, then the good old reporter’s nose comes in handy. And writing up and compiling a story so that it makes sense and tells the story well is perhaps the most underrated skill of all. Good writing is sadly underappreciated.

With a toolkit like that, it is not surprising that governments around the world would rather journalists weren’t at the scene of a demonstration, or sharpening up their introduction of a story about a government cover-up. Perhaps that’s why governments around the world from the USA to China make it especially difficult, or particularly expensive, for journalists to get a visa. And that’s why journalists are targeted, watched, held captive, and in some horrific cases, such as with US journalist James Foley, murdered. Increasingly journalists are working on a freelance basis from war zones and conflicts. As our writer Iona Craig reports from Yemen, this can leave you exposed on two levels – without the protection of being a staff member of a huge news organisation, and without any income if you can’t file stories. That exposure to pressure, and possible violence, also affects bloggers operating as reporters, and is something that worries OSCE’s Dunja Mijatovic (interviewed in our latest magazine), who brought journalists from different countries together in Vienna last month to discuss what needs to be done.

Journalists are still needed by societies, what they do can be very important (although sometimes very trivial too). At the same time that job is changing. In this issue Raymond Joseph’s fascinating article shows how African newsrooms with little money are able to use low-cost technology such as remote-controlled drone cameras to monitor oil spills, as well as less-sexy-sounding data analysis tools to help reporters find out what is going on. He also reports on how newsrooms are working closely with citizen reporters to bring news from regions that were previously unreported. Work being carried out by Naija Voices in Nigeria, and by our Index 2014 award winner Shu Choudhary in India, shows how technology can help augment old-fashioned reporting, getting news to and from remote areas.

News reporting is also taking different forms to reach different audiences, as was brought home to me at the Film Forward conference in Malmö, Sweden, this summer, when US journalist Nonny de la Peña and Danish journalist Steven Achiam showed the audience how interactive news “games” and cartoon-style films are new forms of reportage. Achiam’s Deadline Athen is a journalism game that allows the player to become a journalist in Athens, collecting information about a riot and shows the choices that are available; it gives the players options of where to find out and source the story. La Peña uses her journalistic skills to engage “players” in the experience of being imprisoned in Guantanamo Bay, using real news sources to inform what the “player” experiences so that it is similar to what prisoners experienced. Both Achiam and La Peña argue that these type of approaches will engage and inform different audiences in finding out about the world, audiences that would not be minded to read a newspaper or watch the TV news.

There’s not yet a journalism ethics handbook that covers these approaches. Both La Peña and Achiam are award-winning journalists and have merged their existing set of research skills with a different style. Both talk about sourcing information for their news films, and La Peña offers links to evidence for her virtual-reality storytelling.

These pioneering approaches so far only have small audiences compared to TV news, but will undoubtedly challenge journalists of the future to learn new skills (video and animation look increasingly like core modules).

Interviewing, research and legal knowledge are always going to part of the mix; they are the skills that give journalists the tools to find out what others would rather they didn’t. And that skill package is always going to be vital.

Read the contents of our future of journalism special here. You can buy the print version magazine or subscribe for £32 per year here, or download the app for just £1.79.

You can also join our magazine debate at London’s Frontline Club on 22 October (free entry, but please book).

This article was published on Wednesday 1 October at indexoncensorship.org