Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

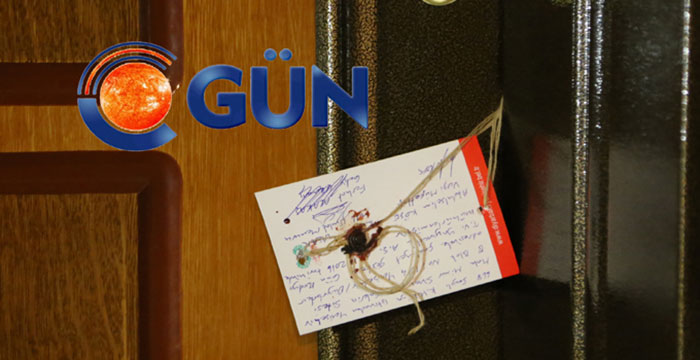

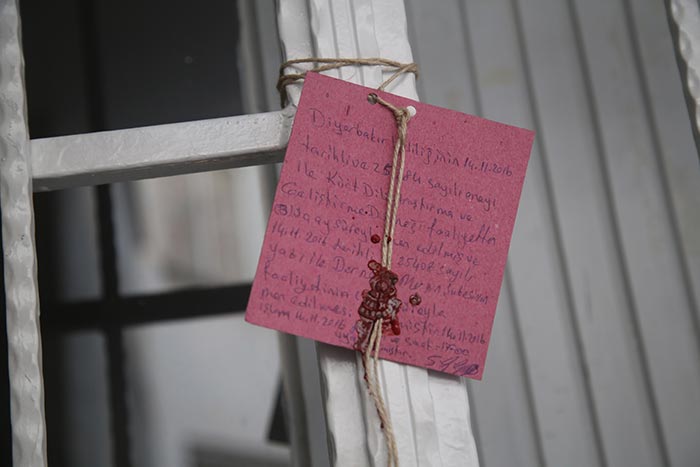

Kürt Yazarlar Dernegi, tarihi Sur ilçesindeki eski Diyarbakir evlerinden birini Özgür Gazeteciler Cemiyeti ile birlikte kullaniyordu. Dernegin es baskanlari Reso Ronahî ile Yildiz Çakar, üyeleriyle birlikte dernegin avlusunda bekliyorlar. Dernegin kapisi yeni mühürlenmis.

The Kurdish Writers Association used one of the old Diyarbakır houses in the historical Sur district together with the Free Journalists Society. The association’s co-presidents, Reso Ronahî and Yıldız Çakar, wait outside the association together with members. The association’s doors have been newly sealed [by authorities].

Jiyan Tv Kürtçenin Zazaki lehçesinde yayin yapan ilk televizyon kanaliydi.

Jiyan TV was the first TV channel to broadcast in the Zaza dialect of Kurdish.

Diyarbakir’da Kürtçe ve Türkçe yayin yapan Özgür Gün Tv, KHK ile kapatildi.

Özgür Gün TV, which broadcast in Diyarbakır in Kurdish and Turkish, was closed by Executive Order.

Pek çok il ve ilçede subeleri bulunan Kurdi Der, Kanun Hükmünde Kararname ile kapatildi.

Kurdi-Der (The Kurdish Language Research and Development Association), which had branches in many towns and cities, was closed by Executive Order.

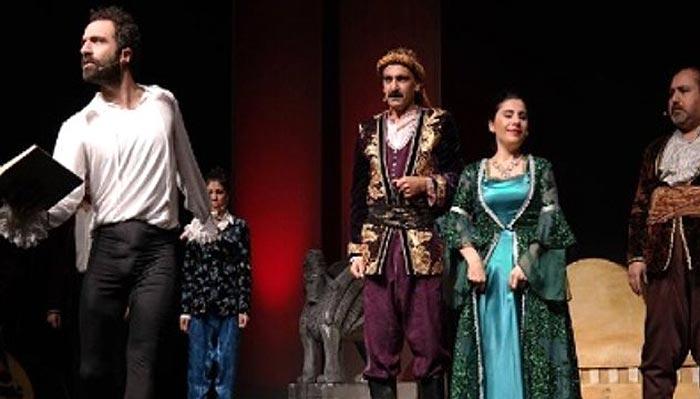

Kürtçe oyunlar sahneleyerek Kürt tiyatrosuna önemli katkilarda bulunan Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi Sehir Tiyatrosu, Olaganüstü Hal’in ilanindan sonra kapatilmadi. Ancak belediyeye kayyim ataninca tiyatrocularin tamami isten çikarildi ve tiyatro fiilen kapatilmis oldu.

The Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre, which has made important contributions to Kurdish theatre by putting on Kurdish-language plays, was not closed after the declaration of a state of emergency. However, when a trustee was appointed to the municipality, all the theatre employees were fired and the theatre was de facto closed down.

Kürtçe oyunlar sahneleyerek Kürt tiyatrosuna önemli katkilarda bulunan Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi Sehir Tiyatrosu, Olaganüstü Hal’in ilanindan sonra kapatilmadi. Ancak belediyeye kayyim ataninca tiyatrocularin tamami isten çikarildi ve tiyatro fiilen kapatilmis oldu.

The Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre, which has made important contributions to Kurdish theatre by putting on Kurdish-language plays, was not closed after the declaration of a state of emergency. However, when a trustee was appointed to the municipality, all the theatre employees were fired and the theatre was de facto closed down.

Dicle Haber Ajansi kurulusundan bu yana çok defa polis tarafindan basildi ve haber konusu oldu. editör ve muhabirleri topluca gözaltina alindi. Internet sitesinin erisimi, 2015’ten kapatildigi 2016 yilina kadar 48 defa engellendi.

From the time the Dicle News Agency was established to the present day, the police have often raided it and it has often been in the news. Its editors and reporters were arrested en masse. Access to the internet site was blocked 48 times in 2015 and 2016.

Dicle Firat Kültür Merkezi, Mezopotamya Kültür Merkezi’nin Diyarbakir’daki subesi. Burada müzik, halk oyunlari, resim gibi kurslar veriliyordu.

The Tigris and Euphrates Cultural Centre was the Diyarbakır branch of the Mesopotamia Cultural Centre. Here there were courses given in areas such as music, folk dancing, and painting.

Kayapinar Belediyesi’ne ait Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi, adini ünlü Kürt sair Cegerxwin’den aliyor. Sanatin bir çok dalinda egitim veren kurum, bugüne kadar yüzlerce ögrenci mezun etti. Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi’nin bir de sergi salonu var.

The Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre belonging to Kayapınar Council takes its name from the famous Kurdish poet Cegerxwîn. Hundreds of students have graduated from the institution, which provides education in many branches of the arts. There is also an exhibition hall at Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Kayapinar Belediyesi’ne ait Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi, adini ünlü Kürt sair Cegerxwin’den aliyor. Sanatin bir çok dalinda egitim veren kurum, bugüne kadar yüzlerce ögrenci mezun etti. Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi’nin bir de sergi salonu var.

The Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre belonging to Kayapınar Council takes its name from the famous Kurdish poet Cegerxwîn. Hundreds of students have graduated from the institution, which provides education in many branches of the arts. There is also an exhibition hall at Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Cewgerxwin Kültür Merkezi.

Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Türkiye’de Kürtçe yayinlanan ilk günlük gazete olan Azadiya Welat, KHK ile kapatildi.

Turkey’s first daily newspaper in Kurdish, Azadiya Welat, was closed with a state of emergency order.

Merkezi Diyarbakir’da bulunan Azadî Tv, Kürtçe ve Türkçe yayin yapiyordu.

Azadî TV, whose headquarters are located in Diyarbakır, used to broadcast in Kurdish and Turkish.

150’den fazla sergiye ev sahipligi yapan Amed Sanat Galerisi, Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi’ne kayyim ataninca sanata kapilarini kapatti.

The Amed Art Gallery, which has played host to over 150 exhibitions, closed its doors to art after a trustee was appointed to Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492093702668-36263af0-9654-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”86316″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]This article is authored by a researcher who has requested anonymity.

Much has been publicised about the crackdown on freedom of expression in the aftermath of the failed coup attempt that transpired on the night of 15 July 2016 in Turkey. This is not the first time that Turkey has experienced a military coup; indeed, violent overthrows of elected governments had already occurred in 1960, 1971 and 1980.

In 1997, the military intervened once more, this by issuing a memorandum that aimed to rein in the Islamist agenda of Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan and his Welfare Party Government. Widely called a “postmodern coup” the military effectively forced him out of office. Each of these coups has engendered a rupture in Turkish political life and has profoundly impacted the realm of arts and culture.

This quality of rupture was perhaps nowhere more contoured than in the military take-over of 12 September 1980, during which the junta under the leadership of Kenan Evren pursued “mass imprisonment, systematic torture, and disappearances” of oppositional, and especially leftist forces. The actual extent of the human rights violations that occurred has yet to be investigated in full but a few figures published by the Istanbul-based Truth, Justice and Memory Center give a glimpse of the social, political and cultural toll of the coup: “according to statistics, approximately 650,000 people were taken into custody, more than 1.5 million were blacklisted by the state, a quarter of a million were put on trial, and 300 lost their lives in various ways.”

Along with disbanding labour unions and limiting freedom of assembly and freedom of the press, the military junta also curtailed academic and artistic expression by establishing the state-controlled Higher Education Council (YÖK) and instituting various mechanisms to pre-screen and censor artworks, especially literary production and films, for years to come. What is often overlooked, however, is that each of these coups has also produced erasure and forgetting in the cultural history of Turkey, not least by curtailing associational life.

Associations that artists were part of were never simply closed, their archives were confiscated too. In this way, the memory of their work was not merely delegitimized but the material traces were likewise destroyed or made inaccessible to the generations that followed. While this dynamic has affected the realm of arts and culture in Turkey in general, the persecution, repression and erasures of Kurdish cultural and artistic production have certainly been the most consistent.

As Kurdish was long classified as an “unrecognised language”, and the existence of Kurds has long been denied in Turkey, Kurdish artistic production has been criminalised and frequently classified as separatist propaganda. Along with individual artists and works of art, Kurdish associational life – as a bedrock of artistic production and cultural reproduction that facilitates the transfer practices, knowledge and memory have been repeatedly targeted; their archives were confiscated and (possibly) destroyed many times over.

What sets this time apart, however, is that the coup attempt actually – and importantly – failed. Yet, the state of emergency declared on 21 July 2016, billed as a necessary tool to investigate the coup and bring the plotters to justice has expanded beyond members of the Gülenist movement to oppositional groups overall by way of Turkey’s vague anti-terrorism legislation. With the extension of the power of the state apparatus, we are, once more witnessing attacks on the field of culture and the arts in general, and Kurdish artistic production in particular.

As investigative journalist Elif İnce reported in January 2017: “Over 1,400 associations and foundations have been shut down with the state of emergency decrees […]. Kurdish arts and culture associations with prominent theatre companies, such as Seyr–î Mesel in Istanbul and various branches of the Mesopotamia Cultural Centre (MKM), are among those permanently shut.”

From September 2016 onwards the AKP government ordered state-appointed trustees to take over the municipalities of several Kurdish cities that had been governed by the pro-Kurdish HDP; their mayors are now facing various charges of aiding and abetting terrorists, and separatist propaganda. These municipalities had been supportive of Kurdish artistic production, both establishing new avenues for artists and assisting initiatives that had been built arduously through grassroots efforts during decades of violence and insecurity. Among the current cases of repression, the de facto closure of the Amed Art Gallery in Diyarbakir through the Ankara-appointed trustee left the city without public facilities to exhibit visual art. The municipal theatre, lauded by the AKP government just a few years ago for performing Hamlet in Kurdish, has likewise been disbanded. The same is true for the city theatres of Batman and Hakkari.

This recent wave of repressions has included sealing off performance and rehearsal spaces, and the confiscation of archives, props, and other equipment. It has extended from municipal theatres in the Kurdish regions to theatre groups affiliated with Kurdish arts and culture associations across the country. Archives are now digital and can be more easily saved, quite in contrast to the 1990s when the MKM were raided repeatedly, threatened by closure, their members often harassed and charged with separatist propaganda based on the mere fact that they pursued artistic production in Kurdish. The Kurdish cultural landscape has been very resilient and experienced in navigating these kinds of repression – and the erasures they engender. But will the same be true for the rest of Turkey’s art world?

Access to the past, to cultural and artistic memory, is intimately connected to freedom of expression. Along with human rights and democratic institutions, cultural memory is once again at stake, and under risk to be erased in Turkey. [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492093371629-c08ef909-721a-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Eric Gill was one of the great British artists of the 20th century – and a sexual abuser of his own daughters. A new exhibition at Ditchling asks: how far should an artist’s life affect our judgment of their work? Read the full article

Art and the Law gives artists and arts organisations guidance about the legal implications of controversial work across five areas: Child Protection, Counter Terrorism, Obscene Publications, Public Order, and Race and Religion

Arts Council England has awarded Index on Censorship funding for the organisation’s work tackling censorship and self-censorship in the arts.

The £100,000 grant will be used to provide workshops for boards and senior management of arts organisations in England and Wales on issues of censorship and other ethical challenges as they affect programming, fundraising and managing controversy. The workshops, delivered with partners Cause4 and the What Next? movement will roll out practical ways to support freedom of expression, so that practitioners feel confident they can create great work — not just safe work.

The programme develops the long-standing work by Index on censorship and self-censorship in the arts, including its ‘Taking the Offensive’ conference in the South Bank, which identified widespread self-censorship in the sector. In 2015, Index — in collaboration with a number of legal advisers and with the support of the Arts Council and Clifford Chance — produced a series of guidance booklets entitled ‘Art and Offence’ that examined various aspects of the law and freedom of expression in England and Wales. The guidelines on public order are being distributed nationwide by the police service to help officers better understand the issues faced by arts venues in hosting potentially controversial work, and police commanders will be invited to training workshops.

The award also builds on research and guidance produced by What Next? on meeting ethical and reputational challenges. With additional funds from Theatre Development Trust, they will develop a nationwide network of local groups who will support colleagues facing ethical challenges. In parallel, and drawing on cases that surface through this nationwide programme, Index will research examples of censorship faced by arts groups in England and Wales to form the basis of a report into the state of free expression in the arts to be published at the end of the programme.

“We are delighted that the Arts Council values this work. A risk-averse culture is putting artistic expression under severe pressure,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship. “In the recent past, we have seen plays, performances and exhibitions being cancelled when faced with a hostile public reaction, or where police have advised closure. A disturbing pattern is emerging, which diminishes the arts.”

Simon Mellor, Deputy Chief Executive, Arts Council England, said: “Some of our greatest art has, over our history, been created by artists taking on the important issues of their day. And they have often done it in a way that audiences have found difficult and uncomfortable. But by provoking a strong response, public understanding of those issues has often deepened. We need to do all we can to create the conditions in which today’s artists can continue to provoke and challenge. The Arts Council is pleased to be supporting this important project by Index on Censorship which will support arts and cultural organisations to help artists take risks, be provocative and, hopefully, create great art.”

Notes to editors

Index on Censorship is a UK-based freedom of expression charity that campaigns against censorship and promotes free expression worldwide. Founded in 1972, Index has published some of the world’s leading writers and artists in its award-winning quarterly magazine, including Nadine Gordimer, Mario Vargas Llosa, Samuel Beckett and Kurt Vonnegut. It also has published some of the greatest campaigning writers from Vaclav Havel to Aung San Suu Kyi.

What Next? is a national movement of arts and cultural organisations, artists, funders, policy makers, institutions, and individuals who come together regularly to articulate and strengthen the role of culture in society. It is an open network of self-forming chapters, building relationships with local and national government, forming alliances outside of the cultural sector, and engaging the public in new and different conversations about the arts. It is chaired by Artistic Director of the Young Vic, David Lan. Over the last four years the What Next? movement has grown organically to encompass 34 chapters around the UK, they bring together individuals, organisations and institutions to work on locally significant issues, and to consider how to contribute to wider action.

Arts Council England champions, develops and invests in artistic and cultural experiences that enrich people’s lives. We support a range of activities across the arts, museums and libraries – from theatre to digital art, reading to dance, music to literature, and crafts to collections. Great art and culture inspires us, brings us together and teaches us about ourselves and the world around us. In short, it makes life better. Between 2015 and 2018, we plan to invest £1.1 billion of public money from government and an estimated £700 million from the National Lottery to help create these experiences for as many people as possible across the country. www.artscouncil.org.uk