Victory for free speech as Bible comedy ban overturned

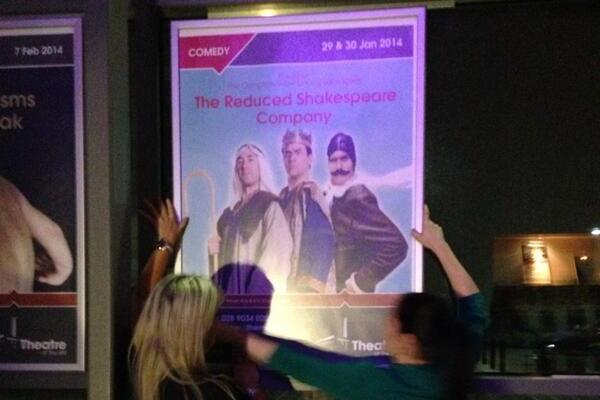

Staff at Newtownabbey’s Theatre on the Mill return promotional posters to hoardings after the local council overturned a ban on the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s The Bible: The Complete Word of God (Abridged). Image Conor Macauley/Twitter

Councillors in Newtownabbey, Co Antrim, Northern Ireland last night voted to overturn a controversial ban on a Bible-based comedy in the town’s theatre. The town had hit international headlines last week after Christian councillors had sought to stop performances of the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s The Bible: The Complete Word of God (abridged).

The Newtownabbey Times reports that town councillors criticised pressure put on the town’s Artistic Council by some members of the Democratic Unionist Party, with one politician denouncing them as “continuity Paisleyites who want to take us back to the Dark Ages.”

The Democratic Unionist Party, which was founded by fundamentalist Christian preacher Ian Paisley, sought to distance itself from the original decision, though its members had been accused of being responsible for pressuring the artistic council into stopping the performances.

The performances will now go ahead on Wednesday and Thursday of this week, as originally scheduled.

This article was posted on 28 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

The Palestinian Authority is worse than Hamas for free speech, activist claims

A leading Palestinian human rights activist has claimed that freedom of speech is far greater under the Hamas regime in Gaza than in the Fatah-controlled West Bank.

A leading Palestinian human rights activist has claimed that freedom of speech is far greater under the Hamas regime in Gaza than in the Fatah-controlled West Bank.

Khalil Abu Shamala, director of the al-Dameer Centre For Human Rights – which works in both Gaza and the West Bank – said that although there were still occasional arrests of Fatah members, “nowadays we don’t document many violations”.

He noted that this was partly down to Hamas’s weakness in the face of international pressures, particularly the breakdown of relations with the Egyptian regime.

In the past, Hamas has made large-scale arrests of journalists and called many others in for questioning, with opposition activists and bloggers facing harassment.

But although abuses still occurred in Gaza, Abu Shamala said that government forces in the Palestinian Authority–controlled West Bank took much harsher action against critics.

“Freedom of expression in Gaza is better than in the West Bank,” he told Index on Censorship. “We have many cases where the PA arrest and attack people because they criticize them on Facebook, and many Facebookers in the West Bank use alternative names, not their real names. But here, they speak without any harassment by Hamas.”

A rift between Hamas and Fatah, which culminated in the Islamist group seizing power in the Strip in 2007, has led to the creation of two near-separate entities in Gaza and the West Bank. Hamas refuses to recognise the Jewish state and is under an embargo by Israel and the international community.

“I don’t know why, but in the West Bank, Palestinian Authority security systems have cooperation and coordination with Israel – and they don’t want to give the opportunity for a third intifada, and they don’t want to allow Hamas or those who are against the Palestinian Authority [to speak out] because they know many of the Palestinians in the West Bank hate the Palestinian Authority,” Abu Shammala continued.

Hamas has previously issued proceedings against Abu Shamala for his outspoken criticism of the Islamist group.

“After they took over Gaza, they wanted from the beginning to impose their Islamic agenda on the society,” he said, adding that his organisations and others had tried to combat these efforts.

The Hamas deputy foreign minister, Ghazi Hamed, denies that his government took any action to silence their critics.

“We are not oppressing people and people can speak loudly, can criticise the government, can criticise Hamas,” said Hamed. “We never put anyone in jail who criticizes Hamas or write something against Hamas. We have different organisations, political parties, even writers, they have full freedom to write what they want.”

Dieudonne is a racist. And he has a right to free speech

It’s coming up to the seventh anniversary of the death of Hrant Dink. Just today, two people have been arrested in connection with his assassination.

It’s coming up to the seventh anniversary of the death of Hrant Dink. Just today, two people have been arrested in connection with his assassination.

Dink, a Turkish-Armenian journalist, understood censorship and free speech more than most. In Turkey, the Armenian genocide of the early 20th century remains taboo, and discussion of it can result in charges under the infamous article 301 of the country’s criminal code – the crime of “insulting Turkishness”.

Recognition of the genocide is an important part of Armenian identity, and many Armenians in the the country itself, Turkey, and the wider diaspora were pleased when, in 2006, French politicians proposed a law making denial of the Armenian genocide illegal. But Dink, understanding that censorious laws hurt everyone, dissented, saying:

“As you know, I have been tried in Turkey for saying the Armenian genocide exists, and I have talked about how wrong this is. But at the same time, I cannot accept that in France you could possibly now be tried for denying the Armenian genocide. If this bill becomes law, I will be among the first to head for France and break the law. Then we can watch both the Turkish Republic and the French government race against each other to condemn me. We can watch to see which will throw me into jail first”

Dink was assassinated, and the bill was blocked, though it reared its head again in 2012, only to be deemed unconstitutional.

One wonders what Dink would have made of president Francois Hollande’s bid to ban public performances by comic and political activist Dieudonne, inventor of the “qeunelle” gesture – an inverted Nazi salute dressed up as an “anti-establishment” gesture. Dieudonne, who ran on an “anti-Zionist” platform in the last election, says there is nothing anti-Semitic about the quenelle, a claim undermined by the spread of pictures of smirking fans quenelling near synagogues, holocaust memorials and even outside the Marseilles Jewish school where three children and a religion teacher were shot down in cold blood in 2012.

It’s important to be clear on this: the quenelle is an anti-Semitic gesture. Dieudonne’s defenders, such illustrious figures as Diane Johnstone and Alain Soral (what we might call the Counterpunch Left), will claim that it is not.

But that is because they are defending Dieudonne’s views, rather than Dieudonne’s right to free speech. It’s an important distinction. Too often, we either attempt to defend free speech by downplaying what’s actually being said (“it’s not that bad”), or claiming it’s something that it’s not (“this isn’t actually racist; it’s, er…”)

Similarly we attempt to justify shutting down free speech by saying something is not a matter of free speech, or worse, resorting to the fact of an existing law or prevalent social mores rather than making a moral argument (as Bernard-Henri Lévy did while discussing the Dieudonne case on theBBC’s Today programme).

A genuine defence of free speech demands that we look what’s happening directly in the eye.

The quenelle is anti-semitic. Dieudonne is anti-semitic. Dieudonne has a right to free speech.

Hrant Dink would have understood that.