Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

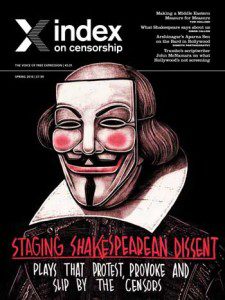

Order your copy of the Staging Shakesearean dissent here.

Order your copy of Index on Censorship here

To mark the release of the spring 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine Index has compiled a reading list of articles from the magazine archives covering the censorship of theatre. The latest issue, Staging Shakespearean Dissent, takes a look at how Shakespeare’s plays have allowed directors to tackle issues that would have otherwise been censored in countries around the world.

August 1982 vol. 11 no. 4

Performances of South African play Egoli, by writer Matsemela Manaka, went ahead at a Johannesburg theatre without being censored, yet the printed version – an extract of which is featured in this article – was banned. Egoli, which means “city of gold”, focuses on the plight of migrant mine workers in South Africa. Its two characters, John Moalusi Ledwaba and Hamilton Mahonga Silwane, were in prison at the same time: one for a political crime, the other for rape and murder. Now they work in the gold mines, while their families attempt to farm in the “homelands”.

Read the full article here.

March 2015 vol. 44 no. 1

Lucien Bourjeily’s 2013 play Will It Pass or Not? was banned by Lebanon’s censorship bureau, yet his 2015 play For Your Eyes Only, Sir was approved after some minor changes, despite the play including scenes from its banned prequel. Aimée Hamilton talks to Bourjeily about why his new play escaped the censors when his previous one didn’t, and what inspired it; and For Your Eyes Only, Sir is translated into English for the first time for Index on Censorship magazine.

Read the full article here.

July 1979 vol. 8 no. 4

Despite government assurances that it was lifting restrictions on Brazilian stage productions in April 1979, theatres were among the most censored over the next decade. Every play had to be submitted to the censor in Brasilia before it was staged, and a complete rehearsal had to take place in the presence of a censor of the town in which the play was being performed. In December 1978 one of Brazil’s best know playwrights Plínio Marcos, notorious for having 18 of his works suppressed without performance, wrote the play Oh! How I Miss the Termite to be read only, believing he could not get the play performed publicly.

Read the full article here.

November 1986 vol. 15 no. 10

In an interview with Czech exile Karel Hvizdala, for inclusion in a book of interviews he was working on, Czechoslovakian playwright Vaclav Havel, who was unable work in his profession in his own country – where nothing he had written had been published or performed since 1969 – speaks about his latest plays Largo Desolato and Temptation.

Read the full article here.

February 1985 vol. 14 no. 1

Karel Kyncl tells the story theatre and film actress Vlasta Chramostová, her Living Room Theatre, and how Shakespeare was used as a form of resistance. In the 1960s and 70s Czechoslovakian actors put on performances of Macbeth in houses, which they called Living Room Theatre. However, Shakespeare was seen as an enemy of socialism by Czechoslovakia police, who began to harass the actors. The actors continued to perform despite pressure from the police but eventually some of these actors were driven into exile.

Read the full article here.

May 2005 vol. 34 no. 2

Janet Steel discusses the censorship Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti faced when the British-Pakistani playwright attempted to put on her production Behzti at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre. The local Sikh community called for the play to be banned, stating it incited racial hatred, which led to Bhatti receiving threats because of her work.

Read the full article here.

Nan Levinson: Bowdler revisited

March 1990 vol. 19 no. 3

Nan Levinson discusses censorship of Romeo and Juliet in textbooks in American schools. Artist Janet Zweig read an article written by a student about the discrepancies between the play in his school textbook and the version he saw on stage. Over 300 lines had been cut from the play, the majority of which contained sexual references. Zweig spoke to publishers and found the publishers that didn’t cut lines from the textbook didn’t sell as many as those who did. She went on to make a book from the 336 lines that were cut from the textbooks, part of which is featured in this article.

Read the full article here.

Dame Janet Suzman: Stage directions in South Africa – June 2014 vol. 43 no.2

Dame Janet Suzman’s 1987 production of Othello in South Africa caused a huge amount controversy due the production showing a relationship between a black man and a white woman during the apartheid. Many people left the production in protest and sent threatening letters, however the play escaped being banned or censored because it was Shakespeare. In this article Suzman discusses why she chose to put on such a controversial production and how through Shakespeare they escaped the censors.

Read the full article here.

November 1998 vol. 27 no. 6

The long awaited revival of a 400-year-old classical opera, in rehearsal at Shanghai’s Kunju Theatre, was called off by the Shanghai Bureau of Culture. It accused the director of introducing “archaic, superstitious and pornographic” elements into his production and vetoed its export first to New York and subsequently to France, Australia and Hong Kong. Mu Dan Ting, (Peony Pavilion), had not been performed in its entire act since it was written by Tang Xianzu in 1598 during the Ming Dynasty, as it was written out of classical repertoire under the communists. However director Yang Lian believes this time round its banning has more to do with political manoeuvering than the nature of the opera itself.

Read the full article here.

August 1980 vol. 9 no. 4 23-28

“Censorship in the theatre has always been more petty and strict than censorship in general – that of literature, for instance. Sadly, it has often been the finest examples of Russian drama that have not reached the stage until several years – sometimes decades – after they were written.” Anna Tamarchenko discusses the censorship of Russian theatre throughout the years.

Read the full article here.

Order your copy of Index on Censorship here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions (just £18 for the year, with a free trial).

This article is part of the autumn 2013 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

In conjunction with the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015, we will be publishing a series of articles that complement many of the upcoming debates and discussions. We are offering these articles from Index on Censorship magazine for free (normally they are held within our paid-for archive) as part of our partnership with the festival. Below is an article by Jemimah Steinfeld and Hannah Leung on the social benefits system in China, taken from the autumn 2013 issue. This article is a great starting point for those planning to attend the Hidden Voices; Censorship Through Omission session at the festival.

Index on Censorship is a global quarterly magazine with reporters and contributing editors around the world. Founded in 1972, it promotes and defends the right to freedom of expression.

When Liang Hong returned to her hometown of Liangzhuang, Henan province, in 2011, she was instantly struck by how many of the villagers had left, finding work in cities all across China. It was then that she decided to chronicle the story of rural migrants. During the next two years she visited over 10 cities, including Beijing, and interviewed around 340 people. Her resultant book, Going Out of Liangzhuang, which was published in early 2013, became an overnight success. In March it topped the Most Quality Book List compiled by the book channel of leading web portal Sina.

Liang’s book is unique, providing a rare opportunity for migrants to narrate their stories. They have been described as san sha (scattered sand) because they lack collective strength and power to change their circumstance. “They are invisible members of society,” Liang told Index. “They have no agency. There is a paradox here. On one hand, villagers are driven away from their homes to find jobs and earn money. But on the other hand, the cities they go to do not have a place for them.”

The central reason? China’s hukou, or household registration system. The hukou, which records a person’s family history, has existed for around 2,000 years, originally to keep track of who belonged to which family. Then, in 1958 under Mao Zedong, the hukoustarted to be used to order and control society. China’s population was divided into rural and urban communities. The idea was that farmers could generate produce and live off it, while excess would feed urban factory workers, who in turn would receive significantly better benefits of education, health care and pensions. But the economic reforms starting in the late 1970s created pressure to encourage migration from rural to urban areas. Today 52 per cent of the population live in a metropolis, with a predicted rise to 66 per cent by 2020.

In this context authorities have debated making changes to the system, or eradicating it altogether. In the 1990s some cities, including Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, started to allow people to acquire a local hukou if they bought property in the city or invested large quantities of money. In Beijing specifically, a local hukou can be acquired by joining the civil service, working for a state-owned company or ascending to the top ranks of the military.

The scope of these exceptions remains small, though, and an improvement is more a rhetorical statement than a reality. “China has been talking about reforming the hukousystem for the last 20 years. Most hukou reform measures so far are quite limited and tend to favour the rich and the highly educated. They have not changed much of the substance,” University of Washington professor Kam Wing Chan, a specialist in Chinese urbanisation and the hukou, told Index.

Thus some 260 million Chinese migrants live as second-class citizens. Shanghai, for example, has around 10 million migrant workers who cannot access the same social services as official citizens.

Of the social services, education is where the hukou system particularly stings. Fully-funded schooling and entrance exams are only offered in the parents’ hometown, where standards are lower and competition for university places higher. Charitable schools have sprung up, but they are often subject to government crackdown. Earlier this year one district in Beijing alone pledged to close all its migrant schools.

It’s not just in terms of social services that migrants suffer. Many bosses demand a local hukou and exploit those without. A labour contract law passed in 2008 remains largely ineffective and the majority of migrants work without contracts. Indeed, it was only in 2003 that migrants could join the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), and to this day the ACFTU does little to recruit them.

The main official channel to voice discontent is to petition local government. Failing that, these ex-rural residents could organise protests or strikes. Given that neither free speech nor the right to assembly is protected in China, all of these options remain largely ineffective, and relatively unlikely. In a rare case in Yunnan province, southwest China, tourism company Xinhua Shihaizi owed RMB8 million (US$1.3 million) to 500 migrant workers for a construction project. With no one fighting their battle, children joined parents and held up signs in public. In this case the company was fined. Other instances are less successful, with reports of violence either at the hands of police or thugs hired by employers being rife.

“Many of them fight or rebel in small ways to get limited justice, because they cannot fight the system on a larger scale,” noted Liang. “For example, my uncle told me that he would steal things from the factory he worked at to sell later. This was a way of getting back at his boss, who was a cruel man.” In lieu of institutional support, NGOs step in. Civil society groups have been legalised since 1994, providing they register with a government sponsor. This is not always easy and migrant workers’ organisations in particular are subject to close monitoring and control. Subsequently only around 450,000 non-profits are legally registered in China, with an estimated one million more unregistered.

But since Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Communist Party of China in March, civil society groups have grown in number. Index spoke to Geoff Crothall from China Labour Bulletin, a research and rights project based in Hong Kong. They work with several official migrant NGOs in mainland China. Crothall said that while these groups have experienced harassment in the past, there has been nothing serious of late.

Migrants themselves are also changing their approach. “Young migrant workers all have cell phones and are interested in technology and know how to use social media. So certainly things such as social media feed Weibo could be a way for them to express themselves,” Liang explained.

It’s not just in terms of new technology that action is being taken. In Pi village, just outside of Beijing, former migrant Sun Heng has established a museum on migrant culture and art. Despite being closely monitored, with employees cautioned by officials against talking to foreigners, it remains open and offers aid to migrants on the side.

There are other indications that times are changing. China’s new leaders have signalled plans to amend the hukou system later this year. Whether this is once again hot air is hard to say. But they are certainly allowing more open conversation about hukou policy reform. Just prior to the release of Liang’s book, in December 2012 the story of 15-year-old Zhan Haite became headline news when Zhan, her father and other migrants took to Shanghai’s People’s Square with a banner reading: “Love the motherland, love children”, in response to not being allowed to continue her education in the city.

Initially there was a backlash. The family were evicted from their house and her father was imprisoned for several weeks. Hostility also came from Shanghai’s hukou holders, who are anxious to keep privileges to themselves. Then something remarkable happened: Haite was invited to write an op-ed for national newspaper China Daily, signalling a potential change in tack.

It’s about time. The hukou system, which has been labelled by some as a form of apartheid, is indefensible on both a moral and economic level in today’s China. Its continuation stands to threaten the stability of the nation, as it aggravates the gulf between haves and have-nots. Reform in smaller cities is a step in the right direction, but it’s in the biggest cities where these gaps are most pronounced. And as the migration of thousands of former agricultural workers to the cities continues, that division is set to deepen if nothing else is done.

Deng Qing Ning, 37, has worked as an ayi in Beijing for the last seven years. At the moment she charges RMB15 (US$2.40) per hour for her routine cleaning services, though she is thinking of increasing her rates to RMB20 to match the market. She hasn’t yet, for fear that current clients will resist.

The word ayi in Mandarin can be used as a generic term for auntie, but it also refers to a cleaner or maid. Most ayi perform a gamut of chores, from taking care of children to cleaning, shopping and cooking.

While ayi in cities like Hong Kong are foreign live-in workers with a stipulated monthly minimum wage (currently HK$3920, US$505), domestic help in China hails from provinces outside of the cities they work. In places like Beijing and Shanghai, the hourly services of non-contractual ayi cost the price of a cheap coffee.

Deng’s story is typical of many ayi who service the homes of Beijingers. She was born in 1976 in a village outside Chongqing, in China’s southwestern Sichuan province, where her parents remain. She came to Beijing in 2006 to join her husband. He had moved up north to find work in construction after the two wed in 2004.

“In Beijing, there are more regulations and more opportunities”, she said, explaining why they migrated to China’s capital. “Everyone leaves my hometown. Only kids and elders remain.”

When she arrived in Beijing, she immediately found work as an ayi through an agency. The agency charged customers RMB25 (US$4) per hour for cleaning services and would pocket RMB10, alongside a deposit. One day, at one of the houses Deng was assigned, her client offered to pay her directly, instead of going through a middleman. The set-up was mutually beneficial.

“When I discovered there was the opportunity to break free, I took it”, she said, adding that many of the cleaning companies rip off their workers.

One perk of being an ayi is Deng’s ability to take care of her daughter. When her daughter was younger and needed supervision, she joined her mother on the job. Now that her daughter is older, Deng is able to pick her up from school.

But this is where the benefits end. Her family does not receive any social welfare. Not having a Beijing hukou means not qualifying for free local education, which makes her nine-year-old daughter a heavy financial burden. Many Beijing schools do not accept migrant children at all.

Aware of these hardships in advance, Deng and her husband were still insistent on bringing their daughter with them to the city, instead of leaving her behind to be raised by grandparents, which is a situation many children of migrant workers face.

“The education in Beijing is better than back home,” she explained. Her daughter attends a local migrant school, a spot secured after they bargained for her to take the place of their nephew. Her brother-in-law’s family had just moved back home because their children kept falling ill.

Deng has to cover some of the fees and finds the urban education system unfair, but she highlights how difficult it is to voice these frustrations.

“Many Beijing kids do not even have good academic records. Our children may be better than theirs. But they take care of Beijingers first.”

She wishes the government would establish more schools; her daughter’s class size has increased three times during the school year. Again, there is nothing they can do and few people she can talk to, she says. It’s not like they have the political or business guangxi (connections) or know a local teacher who can get their daughter admission anywhere else.

Deng’s younger brother, born in 1986, followed his sister to Beijing five years ago and found employment as a construction worker. Three years back Deng received a dreaded phone call. Her brother had been in a serious accident on a construction site, where he tripped over an electrical wire and tumbled down a flight of stairs. He was temporarily blinded due to an injury that impaired his nerves.

The construction site had violated various safety laws. To the family’s relief, the supervisor of the project footed the hospital bills in Beijing’s Jishuitan Hospital, which amounted to more than RMB20,000 (US$3,235). During this time, Deng had to curb her working hours to attend to her brother, but she felt grateful given the possibility of a worse scenario. Her brother’s vision never fully recovered and he returned to their hometown shortly after.

Deng is looking forward to the time when they can all reunite, hopefully once her daughter reaches secondary school. More opportunities are developing in her hometown, which makes a return to Sichuan and relief from her paperless status much more appealing.

Jemimah Steinfeld worked as a reporter in Beijing for CNN, Huffington Post and Time Out Beijing. At present she is writing a book on Chinese youth culture.

Hannah Leung is an American-born Chinese freelance journalist who has spent the past four years in China. She is currently living in Beijing.

© Jemimah Steinfeld and Hannah Leung and Index on Censorship

Join us on 25 October at the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015 for Question Everything an unconventional, unwieldy and disruptive day of talks, art and ideas featuring a broad range of speakers drawn from popular culture, the arts and academia. Moderated by Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

This article is part of the autumn 2013 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

A scene from Can We Talk About This? (Photo: Matt Nettheim for DV8)

As part of our work on art, offence and the law, Julia Farrington, associate arts producer, Index on Censorship, interviewed Eva Pepper, DV8’s executive producer about how she prepared for potential hostility that the show Can We Talk About This? might provoke as it went on tour around the world in 2011-12.

Background

Can We Talk About This?, created by DV8’s Artistic Director Lloyd Newson, deals with freedom of speech, censorship and Islam. The production premiered in August 2011 at Sydney Opera House, followed by an international tour of 15 countries — Sweden, Australia, Hong Kong, France, Italy, Austria, Germany, Greece, Slovenia, Hungry, Spain, Norway, Taiwan and Korea and the UK between August 2011 and June 2012 — and was seen by a 60,000 people.

Extract from publicity of the show:

“From the 1989 book burnings of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, to the murder of filmmaker Theo Van Gogh and the controversy of the ‘Muhammad cartoons’ in 2005, DV8’s production examined how these events have reflected and influenced multicultural policies, press freedom and artistic censorship. In the follow up to the critically acclaimed To Be Straight With You, this documentary-style dance-theatre production used real-life interviews and archive footage. Contributors include a number of high profile writers, campaigners and politicians.”

Q&A

Farrington: How did you set about working with the police for this tour?

Pepper: We focused on the UK with policing; I didn’t speak to any police forces in other countries at all, just in the UK cities we toured to: West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds; Warwick Arts Centre; Brighton Corn Exchange; The Lowry in Manchester and the National Theatre in London. But we did have a risk assessment and risk protocol that we shared with every venue we went to. We let them know the subject matter and the potential risks: security, safety of the audiences, media storms, safety of the people who were working on the show. They dealt either with their in-house security, or, in the UK, they would often alert the police as well.

Farrington: How did your preparations with police vary around the UK?

Pepper: We started with the Metropolitan Police, about six months before and told them our plans and that we would also contact other police forces. The National Theatre had their own contacts with the police who were already on standby. We still kept the MET events unit informed, but they [National Theatre] dealt with the police themselves. They were much more clued up, they had a head of security whom I briefed; we talked quite a lot. I made sure that he was copied in when anything a bit weird came up on the internet.

Our first venue was Leeds and we approached them about six weeks before the UK premiere. There was a bit of nervousness around Leeds, because of the larger Muslim population in the area. But we were only just beginning our liaison with the police and it took a little time to get a response. In the end we approached senior officers, but they often didn’t engage personally, just put us in touch with the appropriate unit to deal with.

Farrington: They didn’t see it as that important?

Pepper: They liked to be alerted that something might happen and they assured us that they were preparing. The venues also had their own police liaison; sometimes there was a bit of conflict if they had their own. I probably ruffled a few feathers when I went to a more senior officer.

Our starting point to the police was a very carefully worded letter which set out who we were. We didn’t ask permission to put it on we just alerted them that we might need police involvement. I did have some calls and a couple of meetings with officers, where they reiterated what is often said, which is that the police’s mandate is to keep the peace. It was made clear that they have as much of a duty to those people who want to protest or potentially might want to protest, as they have to allow us to exercise our freedom of expression. In Leeds nothing happened but there was a certain amount of nervousness around it.

Farrington: Where – at the venue?

Pepper: I think we were probably a bit nervous, and the police took it seriously enough. We had contact numbers to call. They were very much in the loop of the risk assessment.

Farrington: Was there a police presence on the night?

Pepper: I don’t remember seeing anybody. There was security of the venue of course, but regional venues only go so far with security. With some venues we were a little insistent that they get somebody upstairs and downstairs for example.

Farrington: And search bags, that kind of thing?

Pepper: We insisted people check in bags. The risk protocols weren’t invented for Can We Talk About This? They were really invented for To Be Straight With You [DV8’s previous show] and just tightened up for Can We Talk About This?. The risk protocols are just bullet points to get people thinking through scenarios.

Farrington: In general how would you describe your dealings with the police?

Pepper: I think generally supportive but we came to alert them that we might need them – there wasn’t a crisis. They said ‘thanks for letting us know let us deal with it.’ We would have quite liked to go through their risk assessments, but that didn’t happen. I think we were a little bit on their radar. They offered to send round liaison people to discuss practicalities around the office – stuff we hadn’t really thought about. It was a little bit tricky to get their attention.

The things we asked them to look out for were internet activity, if there was something brewing; sounds terribly paranoid. If there were issues around our London office or tour venues like hate mail, suspicious packages and then protests. So protest was just one thing our board was concerned about.

Farrington: Did you do anything else with the venue to prepare them for a possible hostile response from the media or a member of the public?

Pepper: I asked every venue artistic director or chief executive to prepare a statement. Lloyd would have been the main spokesperson for us if anything went wrong, but for a regional venue it is important that you are ready with a response and they all did that.

Farrington: What kind of thing did they say?

Pepper: We have supported this artist for the last 20 years. Lloyd has always been challenging in one way or another. This time he is challenging about this and we are going with him.

Farrington: Did you have any contact with lawyers?

Pepper: We looked carefully at the contents of the show. We had used interviews with real people and we wanted to be sure that nothing said was libellous or factually incorrect. So we had things looked at. The lawyer would say have you thought about that, did you get a release for this, are you using this from the BBC, do you have permission, have you spoken to this person, does he know you are doing it? And sometimes it is yes and sometimes it was a no.

Farrington: They pointed out some bases you hadn’t covered?

Pepper: Maybe one. We were really good and a bit obsessive. Sometimes we thought we didn’t have to ask because the information was in the public domain anyway, based on an interview that has been online for ten years for example. And the lawyer would or wouldn’t agree with that. It was good for peace of mind. That’s the thing with legal advice it doesn’t mean that nobody comes after you, because the law isn’t black and white.

Farrington: Were there some venues that you took the show to that didn’t think it was necessary to make special preparations?

Pepper: We always made them aware and we let them handle it. There are certain things that we always did. We asked them to consider security, and certainly PR. I was quite concerned that it would be a big PR story and then out of the PR story, as we saw with Exhibit B, comes the police. The protests don’t come from nowhere usually, somebody comes and stirs things up.

Farrington: Did you prepare the venue press departments?

Pepper: Yes we did, and we quite consciously had interviews, preview pieces before hand, where Lloyd could give candid interviews about the show. Almost to take the wind out of people’s sails, to put it out in the open so nobody could say they were surprised.

Farrington: How did you prepare with the performers for potential hostility?

Pepper: We talked through the risk procedure with them. We also got some advice from a security specialist, about being more vigilant than usual, noticing things that are out of the ordinary; if somebody picks a fight in the bar after the show, find a way to alert the others. So yes, the security specialist had a meeting with us here in the office, but also came up to Leeds to talk to the performers.

Farrington: Did it create a difficult atmosphere?

Pepper: It did yes, it got a bit edgy. Next time I would not do it around the UK premiere. It took a long time to set all of this up. To find the right people, to get people to take it seriously, to have meetings scheduled.

Farrington: It took time to find the right kind of security specialist?

Pepper: It also took a little while to get straight what we needed. We probably tried to figure it out for ourselves for a long time. And then got somebody in after all, just as maybe we, or the board got a bit more nervous. When you talk about protests you always worry about the general public, but as an employer there are the people who you send on tour who have to defend the show in the bar afterwards, potentially they are the targets.

Farrington: But they were behind the show?

Pepper: Yes, undoubtedly. But it’s an uncomfortable debate. There were so many voices in that show and you didn’t agree with every voice and it was never really said what really is Lloyd’s or DV8’s line. I would say that all the dancers were fine, but sometimes if somebody corners you in a bar it gets squirmy. No one is comfortable with everything.

Farrington: Can you summarise the response to the show?

Pepper: We had everything from 1 to 5 stars. We had people that loved the dance and hated the politics, who loved the politics and hated the dance. Occasionally somebody liked both. Occasionally somebody hated both. The show was discussed in the dance pages, in the theatre pages and in the comments pages. So in terms of the breadth and depth of the discussion we couldn’t have been more thrilled. Then we had dozens of blogs written about the show. For us Twitter really started with Can We Talk About This? and it was a great instrument for us. Social media was largely positive, though some people were picking a fight on Facebook at some point. It was very, very broad and very widely discussed.

Farrington: And did you interact with Twitter or did you let it roll?

Pepper: Mostly we let it roll. As part of the risk strategy we had a prepared statement from Lloyd which was very similar to the forward in the programme and anybody who had any beef would be redirected to the statement.

Farrington: Did the venues take this performance as an opportunity to have post show discussion and debate?

Pepper: Lloyd prefers preshow talks because he doesn’t like people to tell him what they thought of the shows. Quite often there is a quick Q&A before. In UK, we had one in Brighton [organised by Index] and one at the National. We had fantastic ones in Norway after the Breivik killings. In Norway they weren’t sure it was relevant and then the killings happened and then I got the call to say now we need to talk about it.

But having pre-show talks is certainly how we decided to deal with it. There is a conflict with having a white middle-aged atheist put on a show about Islam. But the majority of voices in the show were Muslim voices of all shades of opinion. It wasn’t fiction. It was based on his research and based on people’s stories – writers, intellectuals, journalists, politicians and who had a personal story to tell

Farrington: How did you prepare work with the board regarding potential controversies?

Pepper: Really the work with the board started with the previous show To Be Straight With You that already dealt with homosexuality and religion and culture; how different communities and religious groups make the life of gay people quite unbearable, internationally and in this country. And even then, we started to say, ‘can we say this? are we allowed to criticise these people like this?’ and out of that grew the ‘yes, I do want to talk about this’ because if we don’t a chill develops. Can We Talk About This? was a history about people who had spoken out about aspects of Islam that they were uncomfortable with or against and what happened to them.

Farrington: What kind of board do you need if you are going to be an organisation that explores taboos like this?

Pepper: We have got a fantastic board; it is incredibly responsible and so is Lloyd. There is a very strong element of trust in Lloyd’s work. They wouldn’t be on the board if they didn’t support him. But, as employers, they are aware of their responsibilities to everyone who works for us. As a company we have to be prepared in the eventuality that there is a PR or security disaster. What we were really trying to do was avoid that eventuality. We will never know. Maybe nothing bad would have happened. I think that Lloyd now wishes more people had seen it, that a film had been made, that it was more accessible to study by those who want to. He thinks that maybe we were a bit too careful. But as an organisation, as DV8, as an employer I think that we did the right thing by looking after people.

Farrington: What advice could you give to prepare the ground for doing work that you know will divide opinion and you know could provoke hostility?

Pepper:

E: If you can anticipate this you already have an advantage, but it’s not always possible to second-guess who might find what offensive. But if you know, I would suggest you ask yourself what buttons you are likely to push; you have to be confident why you are pushing them – usually in order to make an important point. It’s a good idea to articulate this reasoning very well in your head and on paper. Then you have got to be brave and get on with your project. Strong partners are invaluable, so try to get support. But in the end it is about standing up and being able to defend what you do.

Farrington: So you think you could have gone a bit further?

Pepper: I think if you prepare well you could go a bit further. I don’t think there is a law in this country that would stop you from being more offensive than we were. Every artist has to decide for themselves what they want to say and why they are saying it, and if they can justify it they can go for it.

A scene from Can We Talk About This? (Photo: Matt Nettheim for DV8)

By Julia Farrington

July 2015

As part of our work on art, offence and the law, Julia Farrington, associate arts producer, Index on Censorship, interviewed Eva Pepper, DV8’s executive producer about how she prepared for potential hostility that the show Can We Talk About This? might provoke as it went on tour around the world in 2011-12.

Background

Can We Talk About This?, created by DV8’s Artistic Director Lloyd Newson, deals with freedom of speech, censorship and Islam. The production premiered in August 2011 at Sydney Opera House, followed by an international tour of 15 countries — Sweden, Australia, Hong Kong, France, Italy, Austria, Germany, Greece, Slovenia, Hungry, Spain, Norway, Taiwan and Korea and the UK between August 2011 and June 2012 — and was seen by a 60,000 people.

Extract from publicity of the show:

“From the 1989 book burnings of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, to the murder of filmmaker Theo Van Gogh and the controversy of the ‘Muhammad cartoons’ in 2005, DV8’s production examined how these events have reflected and influenced multicultural policies, press freedom and artistic censorship. In the follow up to the critically acclaimed To Be Straight With You, this documentary-style dance-theatre production used real-life interviews and archive footage. Contributors include a number of high profile writers, campaigners and politicians.”

Q&A

Farrington: How did you set about working with the police for this tour?

Pepper: We focused on the UK with policing; I didn’t speak to any police forces in other countries at all, just in the UK cities we toured to: West Yorkshire Playhouse in Leeds; Warwick Arts Centre; Brighton Corn Exchange; The Lowry in Manchester and the National Theatre in London. But we did have a risk assessment and risk protocol that we shared with every venue we went to. We let them know the subject matter and the potential risks: security, safety of the audiences, media storms, safety of the people who were working on the show. They dealt either with their in-house security, or, in the UK, they would often alert the police as well.

Farrington: How did your preparations with police vary around the UK?

Pepper: We started with the Metropolitan Police, about six months before and told them our plans and that we would also contact other police forces. The National Theatre had their own contacts with the police who were already on standby. We still kept the MET events unit informed, but they [National Theatre] dealt with the police themselves. They were much more clued up, they had a head of security whom I briefed; we talked quite a lot. I made sure that he was copied in when anything a bit weird came up on the internet.

Our first venue was Leeds and we approached them about six weeks before the UK premiere. There was a bit of nervousness around Leeds, because of the larger Muslim population in the area. But we were only just beginning our liaison with the police and it took a little time to get a response. In the end we approached senior officers, but they often didn’t engage personally, just put us in touch with the appropriate unit to deal with.

Farrington: They didn’t see it as that important?

Pepper: They liked to be alerted that something might happen and they assured us that they were preparing. The venues also had their own police liaison; sometimes there was a bit of conflict if they had their own. I probably ruffled a few feathers when I went to a more senior officer.

Our starting point to the police was a very carefully worded letter which set out who we were. We didn’t ask permission to put it on we just alerted them that we might need police involvement. I did have some calls and a couple of meetings with officers, where they reiterated what is often said, which is that the police’s mandate is to keep the peace. It was made clear that they have as much of a duty to those people who want to protest or potentially might want to protest, as they have to allow us to exercise our freedom of expression. In Leeds nothing happened but there was a certain amount of nervousness around it.

Farrington: Where – at the venue?

Pepper: I think we were probably a bit nervous, and the police took it seriously enough. We had contact numbers to call. They were very much in the loop of the risk assessment.

Farrington: Was there a police presence on the night?

Pepper: I don’t remember seeing anybody. There was security of the venue of course, but regional venues only go so far with security. With some venues we were a little insistent that they get somebody upstairs and downstairs for example.

Farrington: And search bags, that kind of thing?

Pepper: We insisted people check in bags. The risk protocols weren’t invented for Can We Talk About This? They were really invented for To Be Straight With You [DV8’s previous show] and just tightened up for Can We Talk About This?. The risk protocols are just bullet points to get people thinking through scenarios.

Farrington: In general how would you describe your dealings with the police?

Pepper: I think generally supportive but we came to alert them that we might need them – there wasn’t a crisis. They said ‘thanks for letting us know let us deal with it.’ We would have quite liked to go through their risk assessments, but that didn’t happen. I think we were a little bit on their radar. They offered to send round liaison people to discuss practicalities around the office – stuff we hadn’t really thought about. It was a little bit tricky to get their attention.

The things we asked them to look out for were internet activity, if there was something brewing; sounds terribly paranoid. If there were issues around our London office or tour venues like hate mail, suspicious packages and then protests. So protest was just one thing our board was concerned about.

Farrington: Did you do anything else with the venue to prepare them for a possible hostile response from the media or a member of the public?

Pepper: I asked every venue artistic director or chief executive to prepare a statement. Lloyd would have been the main spokesperson for us if anything went wrong, but for a regional venue it is important that you are ready with a response and they all did that.

Farrington: What kind of thing did they say?

Pepper: We have supported this artist for the last 20 years. Lloyd has always been challenging in one way or another. This time he is challenging about this and we are going with him.

Farrington: Did you have any contact with lawyers?

Pepper: We looked carefully at the contents of the show. We had used interviews with real people and we wanted to be sure that nothing said was libellous or factually incorrect. So we had things looked at. The lawyer would say have you thought about that, did you get a release for this, are you using this from the BBC, do you have permission, have you spoken to this person, does he know you are doing it? And sometimes it is yes and sometimes it was a no.

Farrington: They pointed out some bases you hadn’t covered?

Pepper: Maybe one. We were really good and a bit obsessive. Sometimes we thought we didn’t have to ask because the information was in the public domain anyway, based on an interview that has been online for ten years for example. And the lawyer would or wouldn’t agree with that. It was good for peace of mind. That’s the thing with legal advice it doesn’t mean that nobody comes after you, because the law isn’t black and white.

Farrington: Were there some venues that you took the show to that didn’t think it was necessary to make special preparations?

Pepper: We always made them aware and we let them handle it. There are certain things that we always did. We asked them to consider security, and certainly PR. I was quite concerned that it would be a big PR story and then out of the PR story, as we saw with Exhibit B, comes the police. The protests don’t come from nowhere usually, somebody comes and stirs things up.

Farrington: Did you prepare the venue press departments?

Pepper: Yes we did, and we quite consciously had interviews, preview pieces before hand, where Lloyd could give candid interviews about the show. Almost to take the wind out of people’s sails, to put it out in the open so nobody could say they were surprised.

Farrington: How did you prepare with the performers for potential hostility?

Pepper: We talked through the risk procedure with them. We also got some advice from a security specialist, about being more vigilant than usual, noticing things that are out of the ordinary; if somebody picks a fight in the bar after the show, find a way to alert the others. So yes, the security specialist had a meeting with us here in the office, but also came up to Leeds to talk to the performers.

Farrington: Did it create a difficult atmosphere?

Pepper: It did yes, it got a bit edgy. Next time I would not do it around the UK premiere. It took a long time to set all of this up. To find the right people, to get people to take it seriously, to have meetings scheduled.

Farrington: It took time to find the right kind of security specialist?

Pepper: It also took a little while to get straight what we needed. We probably tried to figure it out for ourselves for a long time. And then got somebody in after all, just as maybe we, or the board got a bit more nervous. When you talk about protests you always worry about the general public, but as an employer there are the people who you send on tour who have to defend the show in the bar afterwards, potentially they are the targets.

Farrington: But they were behind the show?

Pepper: Yes, undoubtedly. But it’s an uncomfortable debate. There were so many voices in that show and you didn’t agree with every voice and it was never really said what really is Lloyd’s or DV8’s line. I would say that all the dancers were fine, but sometimes if somebody corners you in a bar it gets squirmy. No one is comfortable with everything.

Farrington: Can you summarise the response to the show?

Pepper: We had everything from 1 to 5 stars. We had people that loved the dance and hated the politics, who loved the politics and hated the dance. Occasionally somebody liked both. Occasionally somebody hated both. The show was discussed in the dance pages, in the theatre pages and in the comments pages. So in terms of the breadth and depth of the discussion we couldn’t have been more thrilled. Then we had dozens of blogs written about the show. For us Twitter really started with Can We Talk About This? and it was a great instrument for us. Social media was largely positive, though some people were picking a fight on Facebook at some point. It was very, very broad and very widely discussed.

Farrington: And did you interact with Twitter or did you let it roll?

Pepper: Mostly we let it roll. As part of the risk strategy we had a prepared statement from Lloyd which was very similar to the forward in the programme and anybody who had any beef would be redirected to the statement.

Farrington: Did the venues take this performance as an opportunity to have post show discussion and debate?

Pepper: Lloyd prefers preshow talks because he doesn’t like people to tell him what they thought of the shows. Quite often there is a quick Q&A before. In UK, we had one in Brighton [organised by Index] and one at the National. We had fantastic ones in Norway after the Breivik killings. In Norway they weren’t sure it was relevant and then the killings happened and then I got the call to say now we need to talk about it.

But having pre-show talks is certainly how we decided to deal with it. There is a conflict with having a white middle-aged atheist put on a show about Islam. But the majority of voices in the show were Muslim voices of all shades of opinion. It wasn’t fiction. It was based on his research and based on people’s stories – writers, intellectuals, journalists, politicians and who had a personal story to tell

Farrington: How did you prepare work with the board regarding potential controversies?

Pepper: Really the work with the board started with the previous show To Be Straight With You that already dealt with homosexuality and religion and culture; how different communities and religious groups make the life of gay people quite unbearable, internationally and in this country. And even then, we started to say, ‘can we say this? are we allowed to criticise these people like this?’ and out of that grew the ‘yes, I do want to talk about this’ because if we don’t a chill develops. Can We Talk About This? was a history about people who had spoken out about aspects of Islam that they were uncomfortable with or against and what happened to them.

Farrington: What kind of board do you need if you are going to be an organisation that explores taboos like this?

Pepper: We have got a fantastic board; it is incredibly responsible and so is Lloyd. There is a very strong element of trust in Lloyd’s work. They wouldn’t be on the board if they didn’t support him. But, as employers, they are aware of their responsibilities to everyone who works for us. As a company we have to be prepared in the eventuality that there is a PR or security disaster. What we were really trying to do was avoid that eventuality. We will never know. Maybe nothing bad would have happened. I think that Lloyd now wishes more people had seen it, that a film had been made, that it was more accessible to study by those who want to. He thinks that maybe we were a bit too careful. But as an organisation, as DV8, as an employer I think that we did the right thing by looking after people.

Farrington: What advice could you give to prepare the ground for doing work that you know will divide opinion and you know could provoke hostility?

Pepper:

E: If you can anticipate this you already have an advantage, but it’s not always possible to second-guess who might find what offensive. But if you know, I would suggest you ask yourself what buttons you are likely to push; you have to be confident why you are pushing them – usually in order to make an important point. It’s a good idea to articulate this reasoning very well in your head and on paper. Then you have got to be brave and get on with your project. Strong partners are invaluable, so try to get support. But in the end it is about standing up and being able to defend what you do.

Farrington: So you think you could have gone a bit further?

Pepper: I think if you prepare well you could go a bit further. I don’t think there is a law in this country that would stop you from being more offensive than we were. Every artist has to decide for themselves what they want to say and why they are saying it, and if they can justify it they can go for it.