16 Sep 2021 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2021, Kyrgyzstan

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/V9L7150bLe0″][vc_column_text]Tatyana Zelenskaya is an illustrator from Kyrgyzstan, working on freedom of expression and women’s rights projects.

Zelenskaya’s illustrations have been featured by Amnesty International, as well as smaller organisations. Numerous Kyrgyzstani news outlets have published Zelenskaya’s work, such as Kloop or Current Time. On 8 March 2020, she was arrested while participating in a peaceful march on International Women’s Day.

Zelenskaya has found inspiration for her work in the waves of anti-government protests that have recently erupted across Russia and Kyrgyzstan. As a graduate from Bishkek’s Academy of Art, Zelenskaya draws on her experience growing up in Kyrgyzstan to highlight and critique key social issues. She originally created artwork to draw attention to the issue of domestic violence, but she has expanded her focus to other societal issues plaguing the country. She has been subject to threats online as a result of her work.

In 2020, she created the artwork for a narrative video game called Swallows: Spring in Bishkek, which features a woman (aspiring to be an outspoken blogger), who helps her friend that was abducted and forced into an unwanted marriage. The game was first released in June 2020 and was downloaded more than 30,000 times in its first two weeks. Its purpose is to break the silence around the issue of bride-kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan, with the aim of preventing them altogether.[/vc_column_text][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/CuOhE4LB5Kg”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Sep 2021 | Awards, Egypt, Fellowship 2021, Kyrgyzstan, News and features, Niger, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_images_carousel images=”117457,117451,117452,117454,117456,117458,117459,117460,117461,117462,117468,117469,117470,117471,117472,117463″ img_size=”full” speed=”3500″ autoplay=”yes”][vc_column_text]The winners of Index on Censorship’s 2021 Freedom of Expression awards have been announced at a ceremony in London hosted by actor, writer and activist Tracy-Ann Oberman.

The Freedom of Expression Awards, which were first held in 2000, celebrate individuals or groups who have had a significant impact fighting censorship anywhere in the world. Winners join Index’s Awards Fellowship programme and receive dedicated training and support. This year’s awards are particularly significant, coming as the organisation celebrates its 50th birthday.

Winners were announced in three categories – art, campaigning and journalism – and a fourth Trustees Award was also presented.

- The 2021 Trustees Award was presented to Arif Ahmed.

Arif Ahmed is a free speech activist and fellow at Gonville & Caius College at the University of Cambridge. In March 2020, Ahmed proposed alterations to the Statement of Free Speech at Cambridge. The proposed amendments were created to make the legislation “clearer and more liberal.” He aimed to protect university campuses as places of innovation and invention. That requires protecting the right to freely and safely challenge received wisdom.

- The 2021 Freedom of Expression Award for Journalism was presented to Samira Sabou.

Samira Sabou is a Nigerien journalist, blogger and president of the Niger Bloggers for Active Citizenship Association (ABCA). In June 2020, Sabou was arrested and charged with defamation under the restrictive 2019 cybercrime law in connection with a comment on her Facebook post highlighting corruption. She spent over a month in detention. Through her work with ABCA, she conducts training sessions on disseminating information on social media based on journalistic ethics. The aim is to give bloggers the means to avoid jail time. Sabou is also active in promoting girls’ and women’s right to freedom of expression, and wants to open her own news agency recruiting young people who want to be innovative in the field of information.

- The 2021 Freedom of Expression Award for Art was presented to Tatyana Zelenskaya

Tatyana Zelenskaya is an illustrator from Kyrgyzstan, working on freedom of expression and women’s rights projects. Zelenskaya has found inspiration for her work in the waves of anti-government protests that have recently erupted across Russia and Kyrgyzstan. In 2020, she created the artwork for a narrative video game called Swallows: Spring in Bishkek, which features a woman who helps her friend that was abducted and forced into an unwanted marriage. The game was downloaded more than 70,000 times in its first month. Its purpose is to break the silence around the issue of bride-kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan, with the aim of preventing them altogether.

- The 2021 Freedom of Expression Award for Campaigning was presented to Abdelrahman Tarek

Abdelrahman “Moka” Tarek is a human rights defender from Egypt, who focuses on defending the right to freedom of expression and the rights of prisoners. Tarek has experienced frequent harassment from Egyptian authorities as a result of his work. He has spent longer periods of time in prison and has experienced torture, solitary confinement, and sexual abuse. Authorities have severely restricted his ability to communicate with his lawyer and family. Tarek was arrested again in September 2020 and in December 2020, a new case was brought against him on terrorism-related charges. Tarek began a hunger strike in protest of the terrorism charges. In January 2021, he was transferred to the prison hospital due to a deterioration in his health caused by the hunger strike.

Index on Censorship chief executive Ruth Smeeth said: “As Index marks its 50th birthday it’s clear that the battle to guarantee free expression and free expression around the globe has never been more relevant. Inspired by the tremendous courage of our award winners, we will continue in our mission to defend free speech and free expression around the globe, give voice to the persecuted, and stand against repression wherever we find it”.

Trevor Philips, chair of the Index on Censorship board of trustees said: “Across the globe, the past year has demonstrated the power of free expression. For many the only defence is the word or image that tells the story of their repression; and for the oppressors the sound they fear most is diversity of thought and opinion. Index exists to ensure that in that battle, freedom wins – both abroad, and as this year’s Trustee award demonstrates here at home too.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Aug 2021 | Afghanistan, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

An Afghan female journalist hosts a radio program at the radio-television channel Ghazal, April 7, 2021.

Mohammad Jan Aria/Xinhua/Alamy Live News

For five days after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban insurgency, Mariam (not her real name) didn’t leave her house. As a professional athlete, this was very unusual. However, 23-year-old Mariam is also one of the city’s up and coming journalists and staying at home did not feel right.

The militant group, known for their regressive ideology and restricting women’s rights and freedoms, had forced many Afghan women to retreat in to the shelter of their homes in the days following the siege. But Mariam had enough. “I wanted to get back to work. I wanted to get out,” she said.

So on Friday, an otherwise normal day off in Kabul, Mariam decided to go to her workplace, a newsroom in the centre of the city. “Around 11.45 am, as I was getting into the car, I got a call from an unknown number. I answered it and the man on the other line, asked, ‘Are you Mariam?’ and I froze in my tracks.”

“He sounded friendly, as though we might have been old friends,” she said.

But something about his voice made her very uncomfortable. Still, she replied, “Yes I am.” He then asked her, “Do you know me?” and she replied, “I don’t and I don’t have your number saved either. Who is this?”

Without answering her question, the man continued, this time in a much less friendly tone. “He identified the location of my office and asked if I worked there. I was so scared, I didn’t reply. He then said, ‘We [the Taliban] are coming for you’ and I immediately hung up and put my phone on airplane mode.”

Mariam is not alone.

In her short career as a journalist and TV presenter, ‘Marzia’ has received many threats from insurgents as well as fundamentalist groups who disapprove of her work in the media. As a woman and as a member of Afghanistan’s persecuted Hazara ethnic group, she was no stranger to threats, but they were always a world away from her vibrant and empowered life in Kabul. Until, that is, the country fell into the hands of the Taliban on 15 August.

‘Fauzia’, another Afghan female journalist, said: “Of course there were challenges of being a journalist in Afghanistan; it was never easy. But I could deal with those because we had platforms, and more importantly, we had the media, to help us fight for our rights.” Fauzia is currently on the run due to the threats she has received.

The Taliban seized control of the majority of the country earlier this month, including the capital. The Afghan president along with many top government officials were forced to flee after being asked to resign on the pretext of creating a transitional government. The militants, however, have taken control of the capital and large parts of the country creating panic and chaos among those who have been outspoken critics of the Taliban.

Since the fall, there has been a rush of Afghans trying to escape the country to avoid persecution from the Taliban who are known to be vengeful. The Journalists in Distress (JID) network, a collaborative effort of media support organisations like the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) are working in collaboration to evacuate Afghan journalists to safety.

Nadine Hoffman, deputy director of the IWMF said: “The race to evacuate Afghan media workers and their families has been the most challenging and complex emergency the press freedom community has faced. Conditions on the ground, particularly at the Hamid Karzai International Airport, have made this gargantuan task feel at times insurmountable.”

“Those individuals we are supporting to evacuate have faced extreme physical duress; they have been beaten, shot at, and threatened in their homes by the Taliban. It is heartbreaking to watch this tragedy unfold. Women journalists voices in Afghanistan are being silenced.”

In a statement on Monday, the CPJ shared that they had registered and vetted the cases of nearly 400 journalists in need of evacuation, and is reviewing thousands of additional requests. Other organisations have similarly large lists of media persons seeking safe passage out of Kabul.

In a press conference held the day after the fall, Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid assured that media will remain independent but said the journalists “should not work against national values”. However, despite the group’s assurance of a full amnesty to those who work in media and the previous government, Afghan journalists do not trust the terror group with a history of violence against the Afghan media.

Already, several journalists have reported being threatened by Taliban members across the country. Meanwhile, the CPJ also documented multiple attacks on the press from the Taliban in the last week, including physical attacks. A female state TV anchor was also forced off the air, underlining the Taliban’s lack of commitment to protecting the rights of journalists.

Several at-risk journalists shared that the Taliban had been visiting their homes collecting information on “those who worked with infidels” and warned that action would be taken later, implying this would happen after the complete withdrawal of foreign forces from Afghanistan.

“We knew sooner or later they would come looking for us so we destroyed all our documents, certificates and IDs that show our work with the Americans,” said a journalist from Nangarhar province, ‘Sahar’. “It was the body of my lifetime of achievements, and I set it all on fire,” she added, the grief evident in her voice.

However, it did little good, as the Taliban came to Sahar’s neighbourhood armed with biometrics devices seeking to identify people with data that was shared with the previous government. “They haven’t come to our house yet. I know they will kill me. They have already killed some of my friends,” referring to the journalists assassinated in March in Jalalabad.

Sahar’s fears are not unfounded. Taliban fighters killed the relative of a Deutsche Welle (DW) journalist on Thursday, while looking for him during a similar door-to-door search as described by Sahar. “They shot dead one member of his family and seriously injured another,” DW reported.

Earlier this month, unidentified gunmen shot and killed Toofan Omar, the owner of Paktia Ghag Radio. Officials in Kabul said Omar was targeted by the Taliban due to his work.

Last month, the group killed and mutilated the body of Danish Siddiqui, an Indian journalist working with Reuters, in Spin Boldak in Kandahar province.

Notably, of the total seven journalists killed in Afghanistan this year, four have been women, highlighting the increased risks women in media like Mariam, Fauzia and Sahar face. Already, earlier this year, the Afghan Journalists Safety Committee reported that nearly 20 per cent of Afghan women quit the media due to the threats they faced. The Afghan media watchdog reported that at least nine provinces in the country had no female journalists employed in the media, essentially depriving women’s voices and presence in the national debate.

These figures are feared to have risen considerably in the last week. “Soon there will be no one left to tell the story of Afghanistan,” Fauzia remarked.

After the call Mariam received on Friday, she made a decision she never thought she would ever have to make. Choking back tears, she said. “I decided to leave my homeland; a country I had previously wanted to serve.”

“I went back home, packed a small bag and left for the airport with my sister. We got on the first plane they [offered]. I don’t even know where we are going but I know we can’t live there.”

[All names of journalists in this article have been changed to protect their identities.][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

10 Aug 2021 | Belarus, Index in the Press, Media Freedom, Uncategorized

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Journalist and former Index colleague Andrei Aliaksandrau

Few things can better describe the spirit of Liverpool fans better than the words etched in gold above the Shankly gates.

When Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein sat down to write the musical Carousel and its anthem, You’ll Never Walk Alone, they did not envisage it becoming a hymn for the masses, cascading down the creaking terrace of the Kop for decades after they penned its stirring lyrics.

It has provided hope in times of sorrow and ecstasy in times of glory at Anfield. Now it is giving comfort to a Belarusian journalist wrongly locked in a jail cell.

Journalist and Liverpool fan Andrei Aliaksandrau previously worked in the UK at the charity Index on Censorship – where I now work on placement from Liverpool John Moores University – for a number of years before returning to his native Belarus. The organisation, set up 50 years ago this year, aims to help those wrongly imprisoned and persecuted for daring to express their views or for telling the truth about what is happening in countries with oppressive regimes. Little did Andrei know; he would one day require our help.

Andrei was detained – along with his girlfriend Irina – in January this year and faces up to 15 years in prison in his home country due to a charge of high treason. His ‘crime’ was helping friends and colleagues pay off the oppressive fines given to them by the Belarusian authorities for their peaceful protests or covering demonstrations as journalists in the unrest following elections last August.

It is an act of generosity that Liverpool fans can recognise as the sort of community spirit and care for your fellow citizen that served them so well after the Hillsborough Disaster and through other projects such as Fans Supporting Foodbanks. Bill Shankly, who was known for welcoming many a supporter to his home, would surely have approved.

The situation in Belarus is dire. The president, Alexander Lukashenko (known often as “Europe’s last dictator”), has been in power since 1994, after the break-up of the Soviet Union of which the country was previously a part. Lukashenko declared himself winner of the 2020 elections with 80% of the vote. Opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya disputed the result and was forced to flee to Lithuania. Following the election, the UK and many other governments said they would not accept the outcome, yet Lukashenko acts with impunity because of ongoing support from Russian leader Vladimir Putin.

Outrage over the result erupted in countrywide protests, demanding Lukashenko step down. But these demonstrations were met with a mass crackdown. Journalists, activists, lawyers and other regular citizens have been arrested and detained by the thousands. Over 1,000 were arrested in a single day in November alone.

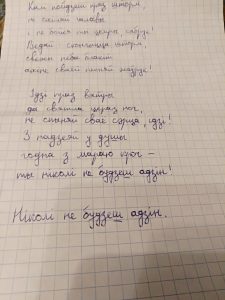

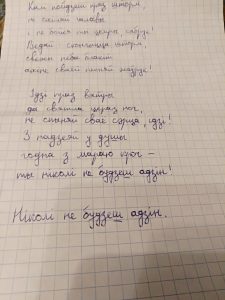

Andrei’s translation of the lyrics of Liverpool FC anthem You’ll Never Walk Alone

As of 6 July, the number of those arrested stands at more than 35,000. According to the Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ), 29 reporters, including Andrei, remain in captivity and 87 have been arrested since January 2021. They have been arrested because Lukashenko does not like what they are writing.

The conditions in Belarusian jails are appalling and a number of those detained have been tortured.

And yet, our former colleague Andrei has seemingly remained upbeat and has not cowed in the face of a regime that wants him silenced. Indeed, it seems that the famous words of Rodgers and Hammerstein have steeled another in times of adversity.

The connection, aside from the fact the song is indeed the club’s official anthem, is obvious. People in Liverpool have faced years of adversity and strife, be it through the bombing of the docks in the Second World War, the strikes of the 1970s and 1980s, or the dreadful injustice of the Hillsborough Disaster in 1989, their ability to draw resilience from a few lines of a musical written in 1945 has always been remarkable.

So, when a Liverpool fan watches, thousands of miles away, as his home country is torn apart by greed and corruption, it is little wonder that his own resolve derives from the very same words.

In a letter to Andrei Bastunets in April, chairperson of the BAJ, the jailed Aliaksandrau offered words of comfort to his close friend, quipping “It turned out so funny. As I went to jail, Liverpool stopped playing properly!”

Even though it was Aliaksandrau behind bars, it was Bastunets receiving reassurance. Aliaksandrau wrote: “In general, there were many reasons to repeat the club’s anthem to myself – You’ll Never Walk Alone.”

“Words of support from letters (sometimes – with the results of the matches) made me sing [and] play it in my head. One day it got to the point where I caught myself mumbling the club’s anthem in Belarusian. It seemed a bit pompous – but it is a hymn.”

“But it seemed to me that it was somehow in tune with the moment, [with my] feelings or mood. So, I decided to share it with you. As an Arsenal fan (sorry for this) you will understand me. At least [you know] what they sing about in Liverpool. And – you will never be alone!”

Andrei’s words remained upbeat despite the Belarusian regime making it even more difficult for Aliaksandrau since his arrest.

Those detained in the country must be released after six months unless they are charged and Andrei was expecting to be released around now, perhaps with a fine as others have been. But the authorities have now slapped the treason charges on him and he faces an uncertain future.

It was also announced in mid-July that Andrei’s lawyer Anton Gashinsky had his license revoked by the authorities. The prominent human rights lawyer also counts among his clients Sofia Sapega, the girlfriend of Roman Protasevich, the journalist who was recently arrested after his Ryanair flight was forcibly redirected by the Belarusian authorities when flying over Belarusian airspace after a faked bomb scare.

Dzmitry Navazhylau, Andrei’s friend and former colleague at Belapan news agency, where Aliaksandrau worked as deputy director, spoke of his friend’s sheer joy that could be found from watching his team.

“Liverpool FC, without exaggeration, is Andrei’s love,” said Navazhylau. “He is one of few Belarusians to have LFC Official Membership. He watched all Liverpool games on the internet with English commentary.”

Andrei used his time in the UK to good effect, he says.

“While working in London, he was lucky enough to see the Reds play live. At one point, there was no way to get a ticket to Anfield. Therefore, Andrei bought a season ticket for Fulham’s home games. He bought a season ticket for another club’s matches to attend one game of his favourite team! But it was worth it!”

Navazhylau recalls: “The most memorable match we watched together was the 2019 UEFA Champions League Final – Liverpool against Tottenham Hotspur. We were dressed in Liverpool kits, chanting, and singing “You’ll Never Walk Alone”. When Salah and Origi scored their goals, and especially after the final whistle, Andrei was as happy as a child.”

Andrei and his friend Dzmitry Navazhylau

It is unknown exactly when his fascination with the Reds began, but it is clear that his upbringing was in a household that was football mad. According to his friend and fellow journalist Kanstantin Lashkevich, Andrei’s father is “probably the only amateur statistician who tracks Belarusian lower-level leagues results”.

Like many fans, Andrei has spent a great deal of time, effort and money has been spent following his team over the years and it is a love for football and club that many on Merseyside can relate heavily to, as is his particular admiration for manager Jürgen Klopp and midfielder James Milner. He also travelled to Munich in 2019, as a journalist, to cover Liverpool’s quarter final Champions League tie with Bayern Munich.

And yet the reality is that, immortal as the words of You’ll Never Walk Alone are, they should not be used to sustain the sanity and goodwill of a man who has given much of his career to the protection of others.

Andrei’s situation is a reminder of how the day-to-day lives of people in a supposed democracy can deteriorate and why protests and free speech are so vital to protecting our individual rights and liberties.

When around 10,000 Liverpool fans marched out of a home game against Sunderland in 2016, protesting the rise of ticket prices, nobody was arrested.

When any person in the UK has to face the courts, for whatever reason, they do not have their legal representation forcibly removed from them.

But both of these things did happen to Andrei Aliaksandrau, whose only crime, many would argue, was embodying the spirit of what it is to be a Liverpool fan.

So how can Liverpool fans help Andrei realise he is not ‘walking alone’? You can sign the petition calling for the release of Andrei and his girlfriend – https://freeandreiandirina.org/ – and write to your local MP calling on the UK government to do more than just condemning the actions of ‘Europe’s last dictator’.

This article was originally printed in issue #276 of Liverpool FC fanzine Red All Over The Land. It has been published online with the kind permission of John Pearman. You can buy a copy outside Anfield on matchdays, or online here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”172″][/vc_column][/vc_row]