24 May 2017 | Art and the Law, Artistic Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Earlier this month Index on Censorship reported on the Glasgow School of Art’s censoring of master of fine arts student James Oberhelm’s work, which the school deemed to contain “inappropriate content”. This was the first and only time a work of art has been censored in the history of the MFA course.

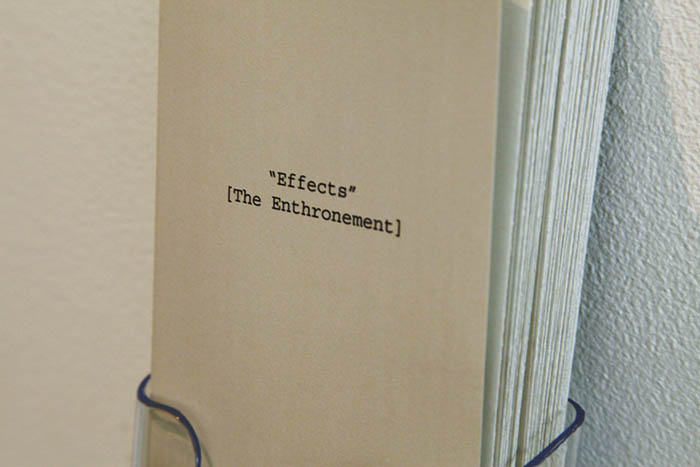

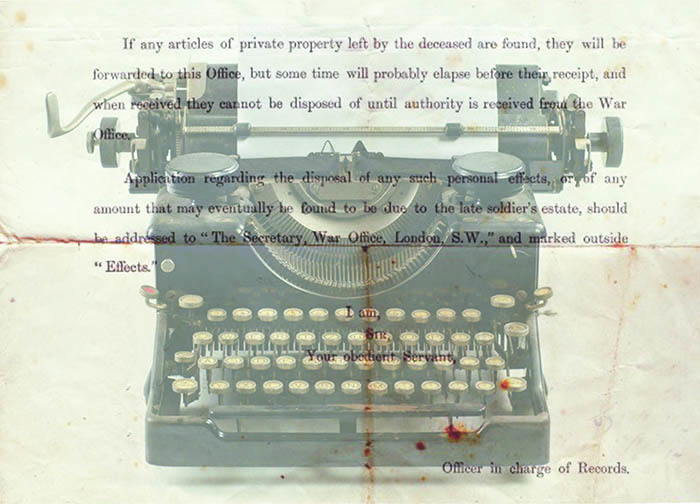

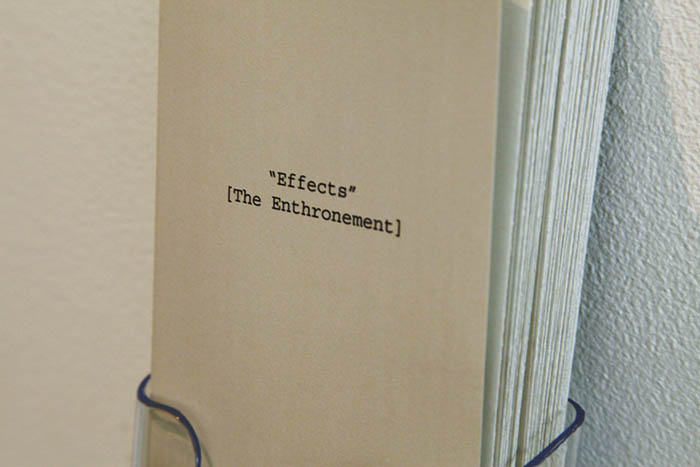

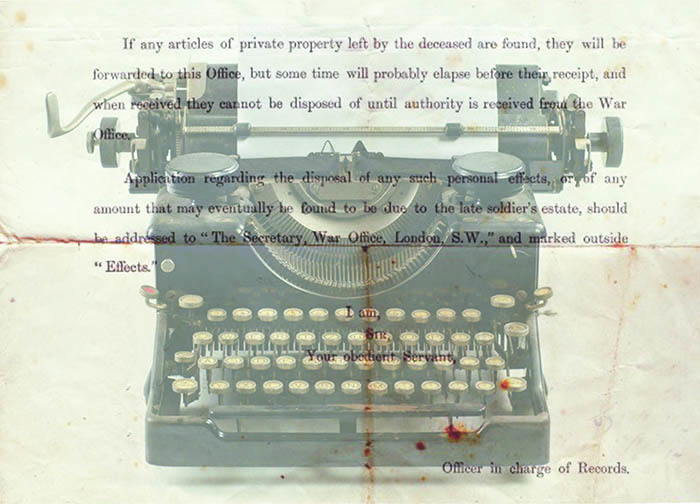

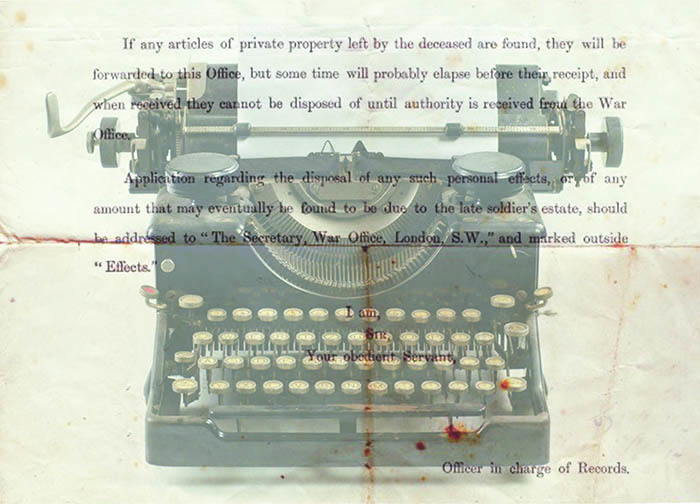

The work, “Effects” [The Enthronement], is an installation dealing with the geopolitics of the Middle East, specifically the centenary of the Sykes-Picot Agreement.

Duncan Campbell, the Irish Turner Prize winner and former student of the Glasgow School of Art, told Index: “In appropriating such demanding representations there is a difficult discussion about responsibility, accountability, and answerability to be had. If an MFA interim show isn’t the place for this, I don’t know where is.”

The school disagrees. In response to a Freedom of Information request by Scottish Pen for “all correspondence, information or documents held by the GSA regarding the decision to remove the piece… as well as the grounds for its removal”, the school said: “The [senior management team] decided that this particular film should not be shown and that the student be supported in moving forward in terms of professional practice and understanding the implications of their work including the presentation of online sources.”

The film in question was a showreel of two videos issued by Al Hayat, Isis’ media branch, in 2014, showing the dismantling of the border between Iraq and Syria as well as an execution sequence, which Oberhelm sourced from the public domain and included in the artwork.

Oberhelm maintains that the response to the FOI request represents a lack of transparency and told Index that his repeated requests to have the reasons for the decision to censor his work in writing, although promised, have been repeatedly denied.

The flyer for masters student James Oberhelm’s banned artwork “Effects” [The Enthronement]

On 11 April Oberhelm was informed via email that his work “is now going to be reviewed by the ‘Prevent Concerns Group’”.

The school’s Prevent Concerns Group consists of 17 executive and non-executive members, made up of senior staff members including the director, the deputy director and the head of the school of fine art. It is “responsible for the strategic development and implementation of measures to meet the Prevent Duty”.

The UK government’s Prevent strategy for safeguarding communities against the threat of terrorism has been criticised by, among others, Index over concerns it undermines the value of freedom by feeding “the very commodity that the terrorists thrive on: fear.”

During a chance encounter on the street with MFA course director Henry Rogers on 26 April, Oberhelm was given insufficient information on the reasons for the artwork’s removal from the course’s interim show. The encounter followed immediately after Rogers’ meeting with Alistair Payne, the head of the school of fine art at the Glasgow School of Art, during which Rogers was informed of the decision about the installation’s viability for exhibition. Rogers then informing Oberhelm that “the decision is no”

In the moments it took for the pair to walk to the JD Kelly building, a number of points were raised, including Prevent. No great amount of detail was given, but it was hinted that Prevent could be, although wasn’t definitely, the basis for the decision.

Rogers also mentioned that an “ethics form” may have been necessary for the work to be shown, but he seemed unsure. “I informed him that I had not been told that an ethics form was required and that I had completed a risk assessment form,” Oberhelm told Index.

The conversation ended with Oberhelm’s request for a written statement explaining the terms under which the work had been censored, which Rogers said would have to be submitted in writing. Oberhelm’s written request was then forwarded to Alistair Payne the following day. During another meeting between the two on 27 April, Oberhelm was told he would receive the minutes of the meeting during which the decision was made. As of yet, the school has not obliged with either any written explanation or the minutes, negating a basic requirement for institutional transparency.

Since Index published the news of the censoring of Oberhelm’s work, the school hasn’t provided us with any further information, despite our requests, and has not granted us an interview.

“[T]he initial FOI has been answered as have follow up questions and that the GSA has nothing to add to this,” a spokesperson for the school told us.

Campbell told Index: “Given the highly consequential decision they have made, I find GSA’s explanation for the removal of James Oberhelm’s artwork inadequate. An honest statement of the committee’s opinions and objections would have at least given everyone affected something to respond to. By being so wilfully non-committal they might as well have offered no explanation at all.”

Campbell is one of many leading contemporary artists who has studied at the Glasgow School of Art and was the fifth artist who studied at the school, and the fourth artist to take part in the school’s MFA programme, to win the prestigious Turner Prize.

When Campbell won in 2014, the director of the school, Tom Inns, said: “This is a great accolade both for Duncan and for The Glasgow School of Art … Duncan and all the previous GSA winners and shortlisted artists are a great inspiration to the current generation of students and the wider visual art community here in Glasgow.”

But given that Campbell’s Turner Prize-winning work, It For Others, contains an image of IRA volunteer Joe McCann, one has to wonder whether the work Inns offered “warm congratulations” for in 2014 would be censored by the school under Prevent if the artist was an MFA student today. After all, Northern Irish dissident republicans do still pose a threat of terrorism, including in Glasgow.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1495703925212-684dd380-cb38-4″ taxonomies=”8964, 7516″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 May 2017 | Art and the Law, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The flyer for master’s student James Oberhelm’s banned artwork “Effects” [The Enthronement]

The work by fine art student James Oberhelm is not being shown in full, but visitors to the exhibition in the art college are told by a flier that the rest of the exhibit has been censored.

The college, whose famous alumni include Peter Capaldi, Liz Lochhead and Charles Rennie Mackintosh, says the ban was in place because of concerns about its “inappropriate content”.

“Effects” [The Enthronement], which was scheduled for exhibition during the first day of Glasgow School of Art’s Interim Show this month, deals with the geopolitics of the Middle East, specifically the century between the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, in which between Britain and France redrew the map of the Middle East, and now.

It was to include a video monitor playing two propaganda videos issues by Isis in 2014: one, entitled The End of Sykes-Picot, shows the destruction of part of the border between Iraq and Syria following the organisation’s capture of territories; the other, Kaser al Hudud, depicts bulldozers destroying the earthen wall along the same border.

A spokesperson for The Glasgow School of Art said: “We deemed the filmic material to be inappropriate for public display as we were concerned that the student’s use and distribution of that material could present an unacceptable risk for the student and the GSA.”

Oberhelm believes that this is the first time in the history of the Glasgow School of Art’s master’s course that such an instance of censorship has occurred, although a representative from the course was unavailable to confirm this. In another instance, a work was deemed too pornographic was granted a separate exhibition space with a disclaimer, Oberhelm said.

“The decision to censor appears to prioritise narrow political considerations over Glasgow School of Art’s own duties and interests: supporting artists in their responsibility to engage with the visual culture of our times, and to participate in meaningful dialogue with the society they are part of,” Oberhelm said in a press release.

A freedom of information request was made to the Glasgow School of Art, requesting: “all correspondence, information or documents held by the GSA regarding the decision to remove the piece…as well as the grounds for its removal.” The school has guaranteed a response no later than 6 June.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1499266681383-29c4ff48-ceee-4″ taxonomies=”8321, 9050, 8401, 9052, 6839, 8964″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Apr 2017 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Kürt Yazarlar Dernegi, tarihi Sur ilçesindeki eski Diyarbakir evlerinden birini Özgür Gazeteciler Cemiyeti ile birlikte kullaniyordu. Dernegin es baskanlari Reso Ronahî ile Yildiz Çakar, üyeleriyle birlikte dernegin avlusunda bekliyorlar. Dernegin kapisi yeni mühürlenmis.

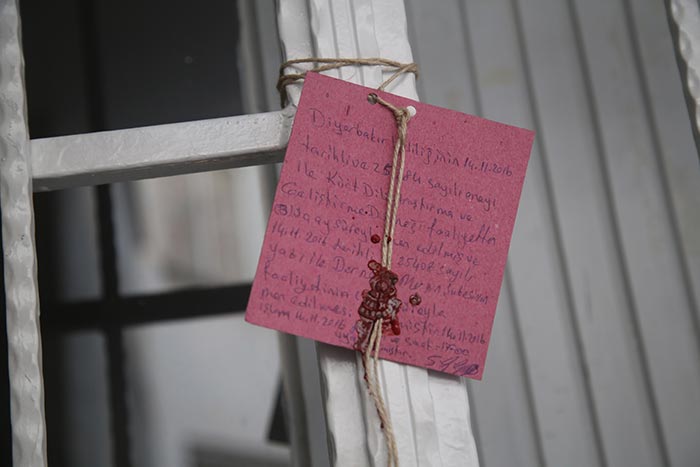

The Kurdish Writers Association used one of the old Diyarbakır houses in the historical Sur district together with the Free Journalists Society. The association’s co-presidents, Reso Ronahî and Yıldız Çakar, wait outside the association together with members. The association’s doors have been newly sealed [by authorities].

Jiyan Tv Kürtçenin Zazaki lehçesinde yayin yapan ilk televizyon kanaliydi.

Jiyan TV was the first TV channel to broadcast in the Zaza dialect of Kurdish.

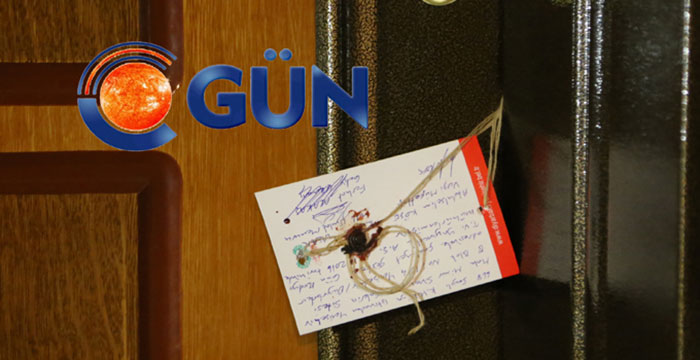

Diyarbakir’da Kürtçe ve Türkçe yayin yapan Özgür Gün Tv, KHK ile kapatildi.

Özgür Gün TV, which broadcast in Diyarbakır in Kurdish and Turkish, was closed by Executive Order.

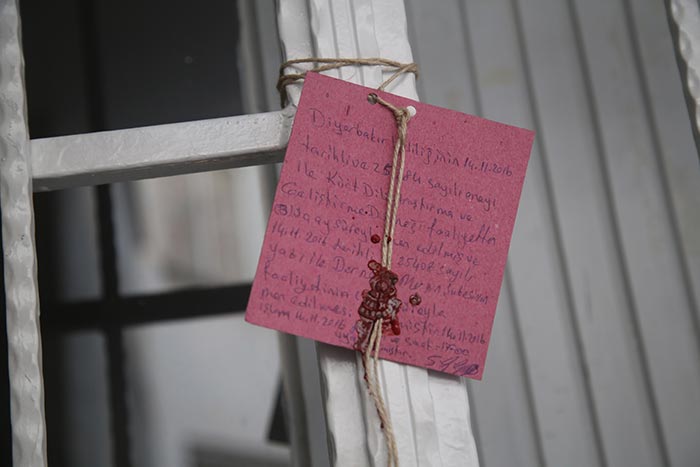

Pek çok il ve ilçede subeleri bulunan Kurdi Der, Kanun Hükmünde Kararname ile kapatildi.

Kurdi-Der (The Kurdish Language Research and Development Association), which had branches in many towns and cities, was closed by Executive Order.

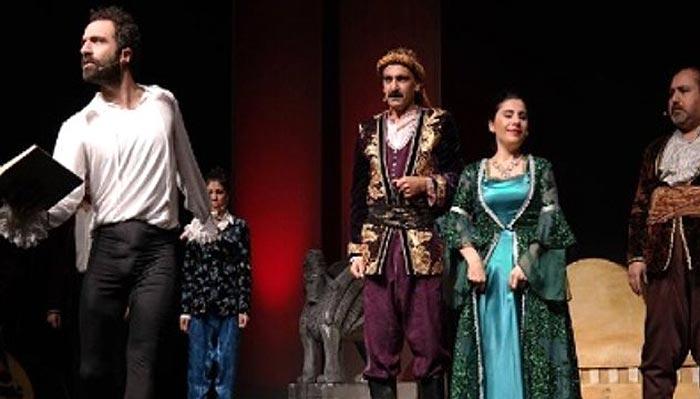

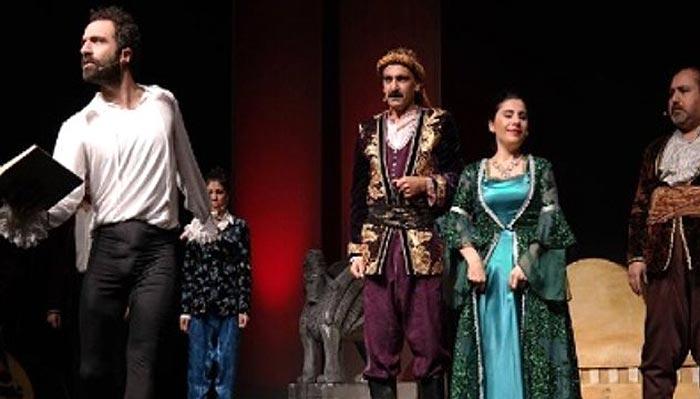

Kürtçe oyunlar sahneleyerek Kürt tiyatrosuna önemli katkilarda bulunan Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi Sehir Tiyatrosu, Olaganüstü Hal’in ilanindan sonra kapatilmadi. Ancak belediyeye kayyim ataninca tiyatrocularin tamami isten çikarildi ve tiyatro fiilen kapatilmis oldu.

The Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre, which has made important contributions to Kurdish theatre by putting on Kurdish-language plays, was not closed after the declaration of a state of emergency. However, when a trustee was appointed to the municipality, all the theatre employees were fired and the theatre was de facto closed down.

Kürtçe oyunlar sahneleyerek Kürt tiyatrosuna önemli katkilarda bulunan Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi Sehir Tiyatrosu, Olaganüstü Hal’in ilanindan sonra kapatilmadi. Ancak belediyeye kayyim ataninca tiyatrocularin tamami isten çikarildi ve tiyatro fiilen kapatilmis oldu.

The Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre, which has made important contributions to Kurdish theatre by putting on Kurdish-language plays, was not closed after the declaration of a state of emergency. However, when a trustee was appointed to the municipality, all the theatre employees were fired and the theatre was de facto closed down.

Dicle Haber Ajansi kurulusundan bu yana çok defa polis tarafindan basildi ve haber konusu oldu. editör ve muhabirleri topluca gözaltina alindi. Internet sitesinin erisimi, 2015’ten kapatildigi 2016 yilina kadar 48 defa engellendi.

From the time the Dicle News Agency was established to the present day, the police have often raided it and it has often been in the news. Its editors and reporters were arrested en masse. Access to the internet site was blocked 48 times in 2015 and 2016.

Dicle Firat Kültür Merkezi, Mezopotamya Kültür Merkezi’nin Diyarbakir’daki subesi. Burada müzik, halk oyunlari, resim gibi kurslar veriliyordu.

The Tigris and Euphrates Cultural Centre was the Diyarbakır branch of the Mesopotamia Cultural Centre. Here there were courses given in areas such as music, folk dancing, and painting.

Kayapinar Belediyesi’ne ait Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi, adini ünlü Kürt sair Cegerxwin’den aliyor. Sanatin bir çok dalinda egitim veren kurum, bugüne kadar yüzlerce ögrenci mezun etti. Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi’nin bir de sergi salonu var.

The Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre belonging to Kayapınar Council takes its name from the famous Kurdish poet Cegerxwîn. Hundreds of students have graduated from the institution, which provides education in many branches of the arts. There is also an exhibition hall at Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Kayapinar Belediyesi’ne ait Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi, adini ünlü Kürt sair Cegerxwin’den aliyor. Sanatin bir çok dalinda egitim veren kurum, bugüne kadar yüzlerce ögrenci mezun etti. Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi’nin bir de sergi salonu var.

The Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre belonging to Kayapınar Council takes its name from the famous Kurdish poet Cegerxwîn. Hundreds of students have graduated from the institution, which provides education in many branches of the arts. There is also an exhibition hall at Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Cewgerxwin Kültür Merkezi.

Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Türkiye’de Kürtçe yayinlanan ilk günlük gazete olan Azadiya Welat, KHK ile kapatildi.

Turkey’s first daily newspaper in Kurdish, Azadiya Welat, was closed with a state of emergency order.

Merkezi Diyarbakir’da bulunan Azadî Tv, Kürtçe ve Türkçe yayin yapiyordu.

Azadî TV, whose headquarters are located in Diyarbakır, used to broadcast in Kurdish and Turkish.

150’den fazla sergiye ev sahipligi yapan Amed Sanat Galerisi, Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi’ne kayyim ataninca sanata kapilarini kapatti.

The Amed Art Gallery, which has played host to over 150 exhibitions, closed its doors to art after a trustee was appointed to Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492093702668-36263af0-9654-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Apr 2017 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”86316″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]This article is authored by a researcher who has requested anonymity.

Much has been publicised about the crackdown on freedom of expression in the aftermath of the failed coup attempt that transpired on the night of 15 July 2016 in Turkey. This is not the first time that Turkey has experienced a military coup; indeed, violent overthrows of elected governments had already occurred in 1960, 1971 and 1980.

In 1997, the military intervened once more, this by issuing a memorandum that aimed to rein in the Islamist agenda of Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan and his Welfare Party Government. Widely called a “postmodern coup” the military effectively forced him out of office. Each of these coups has engendered a rupture in Turkish political life and has profoundly impacted the realm of arts and culture.

This quality of rupture was perhaps nowhere more contoured than in the military take-over of 12 September 1980, during which the junta under the leadership of Kenan Evren pursued “mass imprisonment, systematic torture, and disappearances” of oppositional, and especially leftist forces. The actual extent of the human rights violations that occurred has yet to be investigated in full but a few figures published by the Istanbul-based Truth, Justice and Memory Center give a glimpse of the social, political and cultural toll of the coup: “according to statistics, approximately 650,000 people were taken into custody, more than 1.5 million were blacklisted by the state, a quarter of a million were put on trial, and 300 lost their lives in various ways.”

Along with disbanding labour unions and limiting freedom of assembly and freedom of the press, the military junta also curtailed academic and artistic expression by establishing the state-controlled Higher Education Council (YÖK) and instituting various mechanisms to pre-screen and censor artworks, especially literary production and films, for years to come. What is often overlooked, however, is that each of these coups has also produced erasure and forgetting in the cultural history of Turkey, not least by curtailing associational life.

Associations that artists were part of were never simply closed, their archives were confiscated too. In this way, the memory of their work was not merely delegitimized but the material traces were likewise destroyed or made inaccessible to the generations that followed. While this dynamic has affected the realm of arts and culture in Turkey in general, the persecution, repression and erasures of Kurdish cultural and artistic production have certainly been the most consistent.

As Kurdish was long classified as an “unrecognised language”, and the existence of Kurds has long been denied in Turkey, Kurdish artistic production has been criminalised and frequently classified as separatist propaganda. Along with individual artists and works of art, Kurdish associational life – as a bedrock of artistic production and cultural reproduction that facilitates the transfer practices, knowledge and memory have been repeatedly targeted; their archives were confiscated and (possibly) destroyed many times over.

What sets this time apart, however, is that the coup attempt actually – and importantly – failed. Yet, the state of emergency declared on 21 July 2016, billed as a necessary tool to investigate the coup and bring the plotters to justice has expanded beyond members of the Gülenist movement to oppositional groups overall by way of Turkey’s vague anti-terrorism legislation. With the extension of the power of the state apparatus, we are, once more witnessing attacks on the field of culture and the arts in general, and Kurdish artistic production in particular.

As investigative journalist Elif İnce reported in January 2017: “Over 1,400 associations and foundations have been shut down with the state of emergency decrees […]. Kurdish arts and culture associations with prominent theatre companies, such as Seyr–î Mesel in Istanbul and various branches of the Mesopotamia Cultural Centre (MKM), are among those permanently shut.”

From September 2016 onwards the AKP government ordered state-appointed trustees to take over the municipalities of several Kurdish cities that had been governed by the pro-Kurdish HDP; their mayors are now facing various charges of aiding and abetting terrorists, and separatist propaganda. These municipalities had been supportive of Kurdish artistic production, both establishing new avenues for artists and assisting initiatives that had been built arduously through grassroots efforts during decades of violence and insecurity. Among the current cases of repression, the de facto closure of the Amed Art Gallery in Diyarbakir through the Ankara-appointed trustee left the city without public facilities to exhibit visual art. The municipal theatre, lauded by the AKP government just a few years ago for performing Hamlet in Kurdish, has likewise been disbanded. The same is true for the city theatres of Batman and Hakkari.

This recent wave of repressions has included sealing off performance and rehearsal spaces, and the confiscation of archives, props, and other equipment. It has extended from municipal theatres in the Kurdish regions to theatre groups affiliated with Kurdish arts and culture associations across the country. Archives are now digital and can be more easily saved, quite in contrast to the 1990s when the MKM were raided repeatedly, threatened by closure, their members often harassed and charged with separatist propaganda based on the mere fact that they pursued artistic production in Kurdish. The Kurdish cultural landscape has been very resilient and experienced in navigating these kinds of repression – and the erasures they engender. But will the same be true for the rest of Turkey’s art world?

Access to the past, to cultural and artistic memory, is intimately connected to freedom of expression. Along with human rights and democratic institutions, cultural memory is once again at stake, and under risk to be erased in Turkey. [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492093371629-c08ef909-721a-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]