5 Sep 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Hague, 5 September 2017

Dear members of the International Association of Prosecutors members, executive committee and senate,

In the run-up to the annual conference and general meeting of the International Association of Prosecutors (IAP) in Beijing, China, the undersigned civil society organisations urge the IAP to live up to its vision and bolster its efforts to preserve the integrity of the profession.

Increasingly, in many regions of the world, in clear breach of professional integrity and fair trial standards, public prosecutors use their powers to suppress critical voices.

In China, over the last two years, dozens of prominent lawyers, labour rights advocates and activists have been targeted by the prosecution service. Many remain behind bars, convicted or in prolonged detention for legal and peaceful activities protected by international human rights standards, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Azerbaijan is in the midst of a major crackdown on civil rights defenders, bloggers and journalists, imposing hefty sentences on fabricated charges in trials that make a mockery of justice. In Kazakhstan, Russia and Turkey many prosecutors play an active role in the repression of human rights defenders, and in committing, covering up or condoning other grave human rights abuses.

Patterns of abusive practices by prosecutors in these and other countries ought to be of grave concern to the professional associations they belong to, such as the IAP. Upholding the rule of law and human rights is a key aspect of the profession of a prosecutor, as is certified by the IAP’s Standards of Professional Responsibility and Statement of the Essential Duties and Rights of Prosecutors, that explicitly refer to the importance of observing and protecting the right to a fair trial and other human rights at all stages of work.

Maintaining the credibility of the profession should be a key concern for the IAP. This requires explicit steps by the IAP to introduce a meaningful human rights policy. Such steps will help to counter devaluation of ethical standards in the profession, revamp public trust in justice professionals and protect the organisation and its members from damaging reputational impact and allegations of whitewashing or complicity in human rights abuses.

For the second year in a row, civil society appeals to the IAP to honour its human rights responsibilities by introducing a tangible human rights policy. In particular:

We urge the IAP Executive Committee and the Senate to:

- introduce human rights due diligence and compliance procedures for new and current members, including scope for complaint mechanisms with respect to institutional and individual members, making information public about its institutional members and creating openings for stakeholder engagement from the side of civil society and victims of human rights abuses.

We call on individual members of the IAP to:

- raise the problem of a lack of human rights compliance mechanisms at the IAP and thoroughly discuss the human rights implications before making decisions about hosting IAP meetings;

- identify relevant human rights concerns before travelling to IAP conferences and meetings and raise these issues with their counterparts from countries where politically-motivated prosecution and human rights abuses by prosecution authorities are reported by intergovernmental organisations and internationally renowned human rights groups.

Supporting organisations:

Amnesty International

Africa Network for Environment and Economic Justice, Benin

Anti-Corruption Trust of Southern Africa, Kwekwe

Article 19, London

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

Asia Justice and Rights, Jakarta

Asia Indigenous Peoples Pact, Chiang Mai

Asian Human Rights Commission, Hong Kong SAR

Asia Monitor Resource Centre, Hong Kong SAR

Association for Legal Intervention, Warsaw

Association Humanrights.ch, Bern

Association Malienne des Droits de l’Homme, Bamako

Association of Ukrainian Human Rights Monitors on Law Enforcement, Kyiv

Associazione Antigone, Rome

Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House in exile, Vilnius

Belarusian Helsinki Committee, Minsk

Bir-Duino Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek

Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, Sofia

Canadian Human Rights International Organisation, Toronto

Center for Civil Liberties, Kyiv

Centre for Development and Democratization of Institutions, Tirana

Centre for the Development of Democracy and Human Rights, Moscow

China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, Hong Kong SAR

Civil Rights Defenders, Stockholm

Civil Society Institute, Yerevan

Citizen Watch, St. Petersburg

Collective Human Rights Defenders “Laura Acosta” International Organization COHURIDELA, Toronto

Comunidad de Derechos Humanos, La Paz

Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos, Lima

Destination Justice, Phnom Penh

East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Project, Kampala

Equality Myanmar, Yangon

Faculty of Law – University of Indonesia, Depok

Fair Trials, London

Federation of Equal Journalists, Almaty

Former Vietnamese Prisoners of Conscience, Hanoi

Free Press Unlimited, Amsterdam

Front Line Defenders, Dublin

Foundation ADRA Poland, Wroclaw

German-Russian Exchange, Berlin

Gram Bharati Samiti, Jaipur

Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly Vanadzor, Yerevan

Helsinki Association of Armenia, Yerevan

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, Warsaw

Human Rights Center Azerbaijan, Baku

Human Rights Center Georgia, Tbilisi

Human Rights Club, Baku

Human Rights Embassy, Chisinau

Human Rights House Foundation, Oslo

Human Rights Information Center, Kyiv

Human Rights Matter, Berlin

Human Rights Monitoring Institute, Vilnius

Human Rights Now, Tokyo

Human Rights Without Frontiers International, Brussels

Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, Budapest

IDP Women Association “Consent”, Tbilisi

IMPARSIAL, the Indonesian Human Rights Monitor, Jakarta

Index on Censorship, London

Indonesian Legal Roundtable, Jakarta

Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, Jakarta

Institute for Democracy and Mediation, Tirana

Institute for Development of Freedom of Information, Tbilisi

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH)

International Partnership for Human Rights, Brussels

International Service for Human Rights, Geneva

International Youth Human Rights Movement

Jerusalem Institute of Justice, Jerusalem

Jordan Transparency Center, Amman

Justiça Global, Rio de Janeiro

Justice and Peace Netherlands, The Hague

Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights and Rule of Law, Almaty

Kharkiv Regional Foundation Public Alternative, Kharkiv

Kosovo Center for Transparency, Accountability and Anti-Corruption – KUND 16, Prishtina

Kosova Rehabilitation Center for Torture Victims, Prishtina

Lawyers for Lawyers, Amsterdam

Lawyers for Liberty, Kuala Lumpur

League of Human Rights, Brno

Macedonian Helsinki Committee, Skopje

Masyarakat Pemantau Peradilan Indonesia (Mappi FH-UI), Depok

Moscow Helsinki Group, Moscow

National Coalition of Human Rights Defenders, Kampala

Netherlands Helsinki Committee, The Hague

Netherlands Institute of Human Rights (SIM), Utrecht University, Utrecht

NGO “Aru ana”, Aktobe

Norwegian Helsinki Committee, Oslo

Pakistan Rural Workers Social Welfare Organization (PRWSWO), Bahawalpur

Pensamiento y Acción Social (PAS), Bogotá

Pen International, London

People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD), Seoul

Philippine Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA), Manila

Promo-LEX Association, Chisinau

Protection International, Brussels

Protection Desk Colombia, alianza (OPI-PAS), Bogotá

Protection of Rights Without Borders, Yerevan

Public Association Dignity, Astana

Public Association “Our Right”, Kokshetau

Public Fund “Ar.Ruh.Hak”, Almaty

Public Fund “Ulagatty Zhanaya”, Almaty

Public Verdict Foundation, Moscow

Regional Center for Strategic Studies, Baku/ Tbilisi

Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP), Lagos

Stefan Batory Foundation, Warsaw

Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), Petaling Jaya

Swiss Helsinki Association, Lenzburg

Transparency International Anti-corruption Center, Yerevan

Transparency International Austrian chapter, Vienna

Transparency International Česká republika, Prague

Transparency International Deutschland, Berlin

Transparency International EU Office, Brussels

Transparency International France, Paris

Transparency International Greece, Athens

Transparency International Greenland, Nuuk

Transparency International Hungary, Budapest

Transparency International Ireland, Dublin

Transparency International Italia, Milan

Transparency International Moldova, Chisinau

Transparency International Nederland, Amsterdam

Transparency International Norway, Oslo

Transparency International Portugal, Lisbon

Transparency International Romania, Bucharest

Transparency International Secretariat, Berlin

Transparency International Slovenia, Ljubljana

Transparency International España, Madrid

Transparency International Sweden, Stockholm

Transparency International Switzerland, Bern

Transparency International UK, London

UNITED for Intercultural Action the European network against nationalism, racism, fascism and in support of migrants, refugees and minorities, Budapest

United Nations Convention against Corruption Civil Society Coalition

Villa Decius Association, Krakow

Vietnam’s Defend the Defenders, Hanoi

Vietnamese Women for Human Rights, Saigon

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights, Harare[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1504604895654-8e1a8132-5a81-8″ taxonomies=”8883″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Aug 2017 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

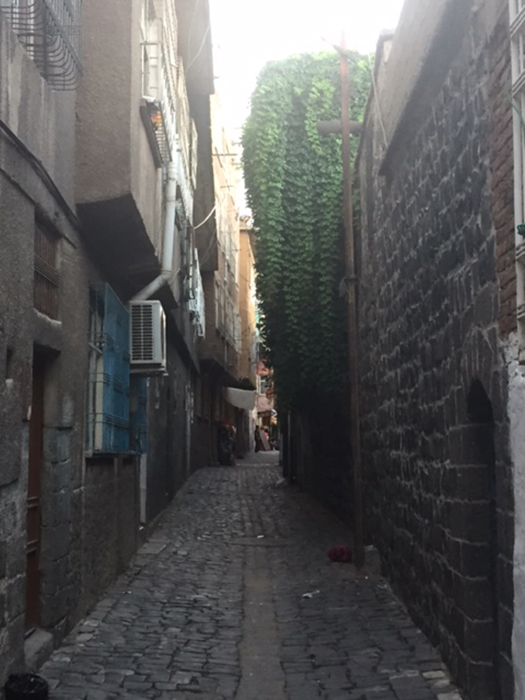

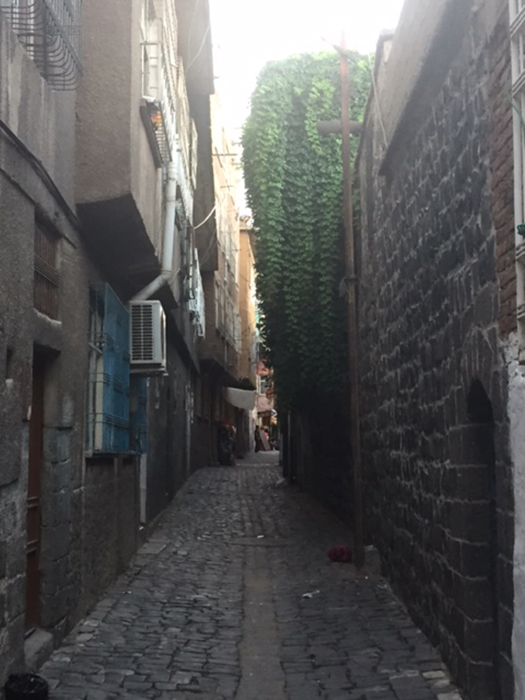

The district of Sur was the first settlement in Diyarbakır, which, according to some sources, has been inhabited for five thousand years and hosted 33 civilisations. The area’s architecture — a rich combination of churches and mosques, mansions and modest homes from different eras — is evidence of its long history and well-established community.

Since June 2016, parts of Sur have demolished as part of an “urban regeneration programme”. In the first stage, homes in the Sur neighbourhoods of Lalebey and Alipaşa were demolished. In the process, the primarily Kurdish communities were destroyed: some families moved away, their connections to their personal history severed; others stayed put, clinging to their homes and their lives in the neighbourhoods with a tenacious resistance to being erased.

The 2016 demolitions were the latest phase in a long process that began in 2009. That’s when the Mayoralties of Diyarbakır and Sur signed an agreement with Turkey’s Environment and Urban Planning Ministry and the Mass Housing Administration to replace the local housing stock with new homes in a style appropriate to the area. Beginning in 2011 with the bulldozing of homes of houses in the Alipaşa neighbourhood, the residents have been at odds with a government they see as inattentive and arbitrary.

During the 1990s, there were violent clashes between Turkey’s military and armed groups aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Thousands of villages were evacuated by state forces. Displaced people became impoverished when they settled in the city of Sur.

When the displaced began arriving in Sur, new housing was built that quickly overwhelmed the area’s mosque and architecture.

Historic buildings were destroyed in order to build housing for the displaced and the area quickly became a slum. In a short time, some of the new housing became unhealthy and unstable.

With neighbourhoods of historic buildings, narrow streets and local culture, the city of Sur would have lost these features through its urban regeneration project. Moreover, the money set aside to buy properties was not enough to allow people to start new lives elsewhere. As a result, the local government suspended the project.

Though the demolitions had been halted because the inhabitants of the area did not want to evacuate their homes and civil society organisations had objected to the destruction of the area’s history and community, an emergency decree issued after the failed July 2016 coup restarted the urban regeneration project.

In May 2017, authorities told residents of Sur’s Lalebey and Alipaşa neighborhoods to evacuate their homes. Families that resisted were told they would be forcibly removed. In the face of the threat, some families left the area. Those that remained had their water and electricity turned off.

Residents of Lalebey and Alipaşa have used the walls of the neighbourhoods to make it clear they do not want to leave their homes.

Residents of Lalebey and Alipaşa have used the walls of the neighbourhoods to make it clear they do not want to leave their homes.

Cumali, sitting in front of his evacuated house, did not want to leave Sur. He has been moved to temporary housing on a road that has not yet been demolished. Cumali says: “I was born in Sur, I grew up, got married. Let us relax. I want to die in Sur.”

Mevlüde Ak was born and grew up in a house in Sur. She gave her house in Sur to her married, unemployed son. She lives with her husband in their small shop. After closing time, they put down beds on the floor and sleep there. Mevlüde Ak says: “They offered me 60,000 Lira for our house. This money would not be enough for us to buy a new home. We’re not leaving. If they wish, let them bring it down on top of us.”

Aynur Güneş’s husband died years ago. She has no children. She lives by selling things like chocolate, gum, crisps in front of her house because it is close to a school. She explains why she does not want to leave Sur as follows: “I know nothing will happen to me here. If something happens: if I fall ill, for example, my neighbours will immediately come to help me. That’s how we grew up in Sur. If I have to live in an apartment I will die.”

Civil society organisations, supported by artists, journalists and politicians, have banded together with Sur residents to fight the ongoing destruction in the neighbourhoods. The campaign is helping to organise petitions and community gatherings, like this one breaking the fast during Ramadan.

8 Aug 2017 | Bahrain, Bahrain News, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Bahraini human rights defender Nabeel Rajab (Photo: The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy)

On 7 August, a Bahraini judge postponed a ruling until 11 September in one of the cases against human rights activist and president of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights Nabeel Rajab.

Rajab is facing trial for tweets and retweets about the war in Yemen in 2015, for which he is charged with “disseminating false rumours in time of war” (Article 133 of the Bahraini Criminal Code) and “insulting a neighboring country” (Article 215 of the Bahraini Criminal Code), and for tweeting about torture in Jau prison, which resulted in a charge of “insulting a statutory body” (Article 216 of the Bahraini Criminal Code).

This case, one of four Rajab faces, began in April 2015. The trial has been postponed 14 times since and carries a sentence of up to 15 years. During the trial Rajab’s son, Adam Nabeel Rajab, tweeted that the state lacks evidence against him.

Rajab, who was an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Advocacy award-winner in 2012, has faced continuous persecution for his activism in Bahrain. He is currently also charged with “spreading false news and statements and malicious rumours that undermine the prestige of Bahrain and the brotherly countries of the GCC, and an attempt to endanger their relations” for a piece published in Le Monde, and “undermining the prestige of the state” for a piece he wrote in The New York Times about his detention. On 10 July, Rajab was sentenced to two years in prison for charges related to 2015 television interviews with Bahraini, Iranian and Lebanese networks which support the Bahraini opposition. Rajab was unable to appear in court due to his poor health last month, and was sentenced in his absence.

Rajab marked one year in detention on 13 June, and for much of this time has been in solitary confinement and unsanitary conditions, which have contributed to his poor health and hospitalisation[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502191511509-ebf34e9e-b840-8″ taxonomies=”716″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

24 Jul 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

People gather in support of the Cumhuriyet defendants as the trial got underway.

Executives and columnists of Turkey’s critical Cumhuriyet daily go on trial this week, beginning Monday 24 July. The indictment seeks prison sentences for the defendants varying between 7.5 to 43 years. The charges for those on the board of the Cumhuriyet Foundation, which oversees the newspaper, include “abuse of power in office,” but all are accused of “supporting terrorist organisations” mainly through changes that have occurred in the paper’s editorial policy following the election of a new board to the foundation in 2013.

The prosecution’s claims are supported by views of several media experts — most of whom are former executives or employees terminated from various positions, according to Aydın Engin, a Cumhuriyet columnist who is also a defendant in the case although he was released pending trial due to his advanced age.

As Engin says “Cumhuriyet changed its editorial policy: this is the essence of the indictment.”

Indeed, the 435-page long document laments, page after page, that Cumhuriyet ditched its traditional, Kemalist, unyieldingly secularist and statist editorial policy and became a more open-minded newspaper.

The prosecutor states that by altering its editorial stance, the newspaper became a supporter of the so-called Fethullahist Terrorist Organization (FETÖ/PYD) — the name Turkish authorities give to the Fethullah Gülen network, which they say was behind last year’s coup attempt –, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK/KCK) and the Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP-C); three organizations with unrelated if not completely opposing worldviews.

“A newspaper changing its editorial policy cannot possibly be the subject of an indictment,” Engin says.

But did Cumhuriyet really change its editorial policy to legitimise the actions of FETÖ/PDY; PKK/KCK and DHKP/C as the prosecutor claims? “Every newspaper makes editorial policy changes as life unfolds. Cumhuriyet also did this. The paper caught up with the general tendencies in society such as increasing demand for freedoms, human rights and a stronger civil society.”

Engin says many of the witnesses who have testified against the Cumhuriyet journalists have been discredited as media professionals. “When I told the prosecutor that I will not respond to claims by people who have no reputation as journalists, he showed me a post by Professor Halil Berktay, who tweeted that ‘Cumhruiyet has become FETÖ’s media outlet.’ The prosecutor said, ‘This from a professor. Who are you to deny its validity?’

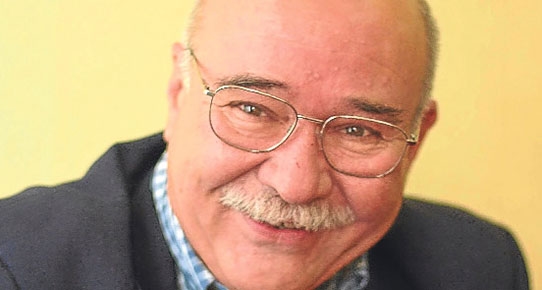

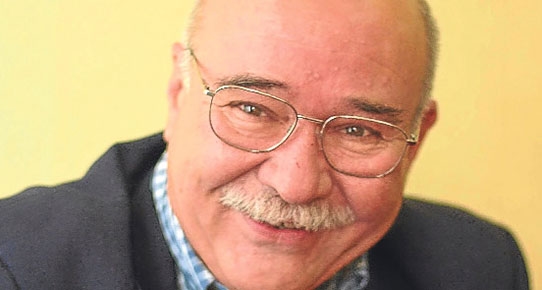

Engin: old and tired

Will any of the Cumhuriyet journalists be released at the end of this week? “I don’t even want to being to make any assumptions. This is not a legal trial; it is entirely political,” Engin replies, adding: “I strongly need them, personally, because I am 76 and tired,” says the energetic-looking journalist, who, as he speaks, is interrupted by someone asking him to sign a financial document. “See, I don’t even know what I just signed, I don’t know anything about these things.”

According to Engin, because those imprisoned are the key people to the newspaper’s operations, Cumhuriyet is now “half-paralyzed.”

But really, who are those in prison?

“Our brightest colleagues are in the can. Akın Atalay, is our CEO and I am a first-hand witness of how he has managed to keep the newspaper on its feet. Murat Sabuncu, he is perhaps one of the two or three finest journalists I know who can smell the news. He is publicly unheard of but Önder Çelik: he has been with Cumhuriyet for 35 years, he is the finest expert at things such as analyzing circulation reports, maintaining relations with printing houses; following paper prices..”

“I really need them to get out, but I don’t want to be dreaming.”[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Turkey” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:30|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fmappingmediafreedom.org%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors press freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area nations.

As of 24/07/2017, there were 496 verified reports of media freedom violations associated with Turkey in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”94623″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://mappingmediafreedom.org/#/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]The journalists on trial for the first time on 24 – 28 July:

Akın Atalay (Cumhuriyet Foundation Executive President; imprisoned since Nov. 12, 2016): Facing 11 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Akın Atalay (Cumhuriyet Foundation Executive President; imprisoned since Nov. 12, 2016): Facing 11 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Atalay graduated from İstanbul University Law School in 1985. He has acted as the founding member of a number of civil society organisations and his academic studies on press freedom and the law have appeared in a large number of academic journals and newspapers. Since 1993, he has represented Cumhuriyet columnists and reporters as legal counsel. Currently, he is the newspaper’s executive president.

Bülent Utku (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board Member, attorney representing Cumhuriyet; imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Bülent Utku (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board Member, attorney representing Cumhuriyet; imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Utku has worked as an attorney for 33 years. Since 1993, he has worked as a lawyer for Cumhuriyet columnists and journalists. He is also a member of the Cumhuriyet Foundation’s Board of Directors.

Murat Sabuncu (editor-in-chief, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” [Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 314/2]

Murat Sabuncu (editor-in-chief, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” [Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 314/2]

Sabuncu has been a journalist for 20 years. He started working at Cumhuriyet in 2014 as the newsroom coordinator. In July 2016, he took the helm as editor-in-chief.

Kadri Gürsel (publications advisor, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Kadri Gürsel (publications advisor, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

A journalist of 28 years, Gürsel started writing columns in Cumhuriyet in May 2016. He assumed the position of publications advisor for the newspaper in September 2016.

Güray Öz (board member, news ombudsman, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 8.5 to 22 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Güray Öz (board member, news ombudsman, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 8.5 to 22 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Öz has been a journalist for 21 years. He has worked at Cumhuriyet since 2006. He is a columnist for the newspaper and has been its ombudsman since 2013. Öz is also on the board of directors of the Cumhuriyet Foundation.

Önder Çelik (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Önder Çelik (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Önder Çelik has been a newspaper administrator for 35 years. He has worked as the print coordinator for the newspaper between 1981 – 1998. He returned to the same position in 2002 after a hiatus. He has been an executive board member since 2014 as well as a board member of the foundation.

Turhan Günay (editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet’s book supplement, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 8.5 to 22 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Turhan Günay (editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet’s book supplement, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 8.5 to 22 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

A journalist for 48 years, Günay has been with Cumhuriyet since 1987. For the past 25 years, he has worked as the chief editor for Cumhuriyet’s literary supplement, the country’s longest running weekly publication on books. The indictment insists he is a board member of the foundation; although he isn’t; a fact he reiterated in his testimony to the prosecutor.

Musa Kart

Musa Kart (Cartoonist, board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016) Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Musa Kart, one of Turkey’s most renowned cartoonists, has been drawing political cartoons for 33 years. He has been a Cumhuriyet journalist since 1985. For the past six years, Kart has drawn the front-page cartoons for Cumhuriyet.

Hakan Karasinir (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hakan Karasinir (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hakan Karasinir has been a journalist for 34 years. He has been with Cumhuriyet for 34 years. In the past he has held various editorial positions, including serving as the newspaper’s managing editor between 1994 and 2014. Since 2014, he has also written columns in the newspaper.

Mustafa Kemal Güngör (attorney, board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Mustafa Kemal Güngör (attorney, board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Mustafa Kemal Güngör has been a lawyer for 31 years. He has defended Cumhuriyet journalists and columnists in court since 2013.

Can Dundar

Can Dündar (former editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet, currently resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Perhaps the most internationally famous of all Cumhuriyet defendants, Can Dündar was the editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet until August 2016. He was arrested in November 2015 after Cumhuriyet published footage suggesting that the Turkish government sent weapons to armed jihadi groups in Syria. He was released in February 2016, a few months after which he moved to Germany where he currently resides.

Orhan Erinç (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board President, columnist). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member” ; four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Orhan Erinç (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board President, columnist). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member” ; four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Veteran journalist Orhan Erinç, who worked for Cumhuriyet as a young reporter, returned to the newspaper in 1993 as its publications advisor. For nearly half a decade, Erinç also held the position of vice president at Turkish Journalists’ Association. He is also a columnist for Cumhuriyet.

Aydın Engin (columnist, released under judicial control measures). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Aydın Engin (columnist, released under judicial control measures). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Cumhuriyet columnist Aydın Engin has been a journalist since 1969. He has participated in the founding process for many news outlets, including Turkey’s Birgün daily. He worked as a columnist and reporter for Cumhuriyet between 1992 and 2002. He returned to the newspaper in 2015.

Hikmet Çetinkaya (columnist, board member, released under judicial control). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hikmet Çetinkaya (columnist, board member, released under judicial control). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Çetinkaya has been with Cumhuriyet for three decades. In the past, the columnist worked as the İzmir Bureau Chief of the newspaper. He was also tried in 2015 along with Cumhuriyet columnist Ceyda Karan for reprinting the Charlie Hebdo cartoons in his column.

Ahmet Şık (Correspondent, imprisoned since Dec. 30, 2016). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Ahmet Şık (Correspondent, imprisoned since Dec. 30, 2016). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

No stranger to Turkish prisons, Ahmet Şık worked as a reporter for Cumhuriyret, Evrensel, Yeni Yüzyıl, Nokta and Reuters between 1991 and 2007. He remained in prison for a year in 2011 in an investigation about a shady gang called Ergenekon, believed to be nested within Turkey’s state hierarchy. He is known as one of the most vocal critics of the Fethullah Gülen network.

İlhan Tanır (former Washington correspondent, resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

İlhan Tanır (former Washington correspondent, resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

İlhan Tanır previously reported from Washington for Cumhuriyet. His reports and analyses have appeared in many national and international publications. He currently resides in the United States.

Bülent Yener (Finance Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Bülent Yener (Finance Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

A former financial affairs manager with Cumhuriyet, Bülent Yener was released after one day in custody.

Günseli Özaltay (Accounting Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Günseli Özaltay, the newspaper’s accounting manager, was released after one day in custody.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1500894514864-6349d62e-4ed7-3″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Akın Atalay (Cumhuriyet Foundation Executive President; imprisoned since Nov. 12, 2016): Facing 11 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Akın Atalay (Cumhuriyet Foundation Executive President; imprisoned since Nov. 12, 2016): Facing 11 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust” Bülent Utku (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board Member, attorney representing Cumhuriyet; imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust”

Bülent Utku (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board Member, attorney representing Cumhuriyet; imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and “abusing trust” Murat Sabuncu (editor-in-chief, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” [Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 314/2]

Murat Sabuncu (editor-in-chief, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” [Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 314/2] Kadri Gürsel (publications advisor, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Kadri Gürsel (publications advisor, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”  Güray Öz (board member, news ombudsman, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 8.5 to 22 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Güray Öz (board member, news ombudsman, columnist, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2015). Facing 8.5 to 22 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”  Önder Çelik (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Önder Çelik (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and four counts of “abuse of power in office”  Turhan Günay (editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet’s book supplement, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 8.5 to 22 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Turhan Günay (editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet’s book supplement, imprisoned since Nov. 5, 2016). Facing 8.5 to 22 years for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and a single count of “abuse of power in office”

Hakan Karasinir (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hakan Karasinir (board member, imprisoned since Nov. 5). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member” and two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Orhan Erinç (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board President, columnist). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member” ; four counts of “abuse of power in office”

Orhan Erinç (Cumhuriyet Foundation Board President, columnist). Facing 11.5 to 43 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member” ; four counts of “abuse of power in office”  Aydın Engin (columnist, released under judicial control measures). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Aydın Engin (columnist, released under judicial control measures). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”  Hikmet Çetinkaya (columnist, board member, released under judicial control). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”

Hikmet Çetinkaya (columnist, board member, released under judicial control). Facing 9.5 to 29 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”; two counts of “abuse of power in office”  Ahmet Şık (Correspondent, imprisoned since Dec. 30, 2016). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

Ahmet Şık (Correspondent, imprisoned since Dec. 30, 2016). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”  İlhan Tanır (former Washington correspondent, resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”

İlhan Tanır (former Washington correspondent, resides abroad). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organisation while not being a member”  Bülent Yener (Finance Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”

Bülent Yener (Finance Manager). Facing 7.5 to 15 years in prison for “helping a terrorist organization while not being a member”