8 Mar 2014 | Azerbaijan News, News and features

International Women’s Day is a day to remember violence against women, the education gap, the wage gap, online harassment, everyday sexism, the intersection between sexism and other -isms, and a whole host of other issues to make us realise we’ve still got a long way to go. A day to demand continued progress, and a day to pledge to work to achieve it.

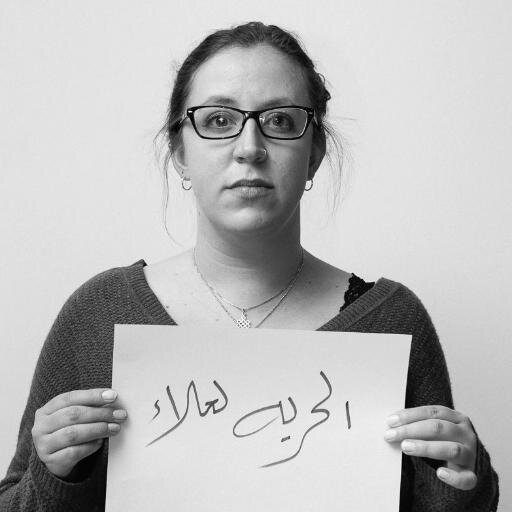

But it is also a day to celebrate. To appreciate the fantastic achievements that are made every day, everywhere, by women from all walks of life. It’s a day to be grateful to the women who dedicate their lives to fighting on the front lines to protect rights vital to us all. We want to shine the spotlight on women who have stood up for freedom of expression when it’s not the easy or popular thing to do, against fierce opposition and often at great personal risk. The following eight women have done just that. We know there are many, many more. Tell us about your female free speech hero in the comments or tweet us @IndexCensorship.

Meltem Arikan — Turkey

Meltem Arikan

Arikan is a writer who has long used her work to challenge patriarchal structures in society. He latest play “Mi Minor” was staged in Istanbul from December 2012 to April 2013, and told the story of a pianist who used social media to challenge the regime. Only a few months after, the Gezi Park protests broke out in Turkey. What started as an environmental demonstration quickly turned into a platform for the public to express their general dissatisfaction with the authorities — and social media played a huge role. Arikan was one of many to join in the Gezi Park movement, and has written a powerful personal account of her experiences. But a prominent name in Turkey, she was accused of being an organiser behind the protests, and faced a torrent of online abuse from government supporters. She was forced to flee, now living in exile in the UK.

I realised that we were surrounded, imprisoned in our own home and prevented from expressing ourselves freely.

Anabel Hernández — Mexico

Anabel Hernández (Image: YouTube)

Hernández is a Mexican journalist known for her investigative reporting on the links between the country’s notorious drug cartels, government officials and the police. Following the publication of her book Los Señores del Narco (Narcoland), she received so many death threats that she was assigned round-the-clock protection. She can tell of opening the door to her home only to find a decapitated animal in front of her. Before Christmas, armed men arrived in her neighbourhood, disabled the security cameras and went to several houses looking for her. She was not at home, but one of her bodyguards was attacked and it was made clear that the visit — from people first identifying themselves as members of the police, then as Zetas — was because of her writing.

Many of these murders of my colleagues have been hidden away, surrounded by silence – they received a threat, and told no one; no one knew what was happening…We have to make these threats public. We have to challenge the authorities to protect our press by making every threat public – so they have no excuse.

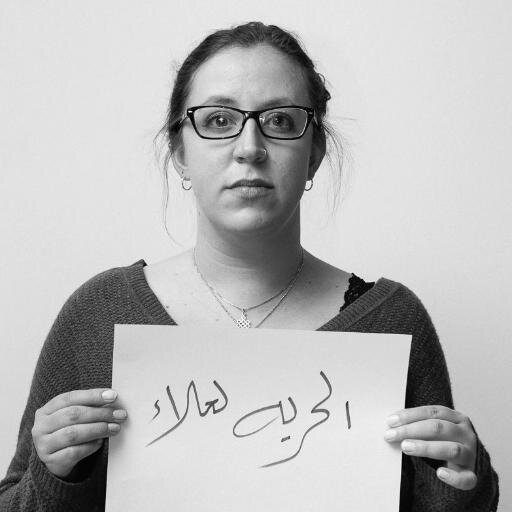

Amira Osman — Sudan

Amira Osman (Image: YouTube)

Amira Osman, a Sudanese engineer and women’s rights activist was last year arrested under the country’s draconian public order act, for refusing to pull up her headscarf. She was tried for “indecent conduct” under Article 152 of the Sudanese penal code, an offence potentially punishable by flogging. Osman used her case raise awareness around the problems of the public order law. She recorded a powerful video, calling on people to join her at the courthouse, and “put the Public Order Law on trial”. Her legal team has challenged the constitutionality of the law, and the trial as been postponed for the time being.

This case is not my own, it is a cause of all the Sudanese people who are being humiliated in their country, and their sisters, mothers, daughters, and colleagues are being flogged.

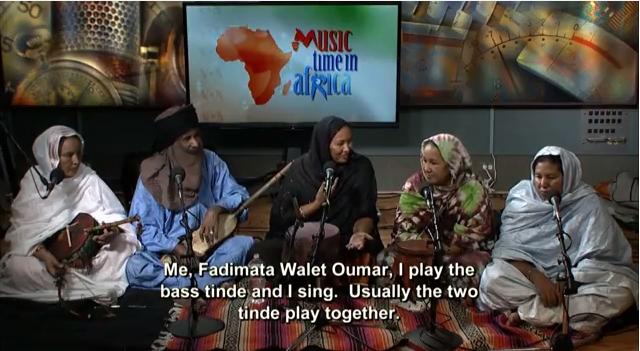

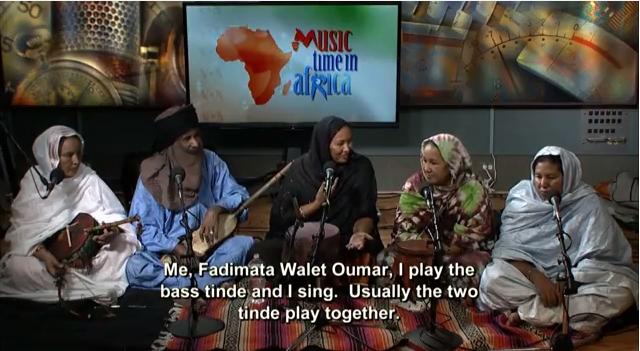

Fadiamata Walet Oumar — Mali

Fadiamata Walet Oumar with her band Tartit (Image: YouTube)

Fadiamata Walet Oumar is a Tuareg musician from Mali. She is the lead singer and founder of Tartit, the most famous band in the world performing traditional Tuareg music. The group work to preserve a culture threatened by the conflict and instability in northern Mali. Ansar Dine, an islamists rebel group, has imposed one of the most extreme interpretations of sharia law in the areas they control, including a music ban. Oumar believes this is because news and information is being disseminated through music. She fled to a refugee camp in Burkina Faso, where she has continued performing — taking care to hide her identity, so family in Mali would not be targeted over it. She also works with an organisation promoting women’s rights.

Music plays an important role in the life of Tuareg women. Our music gives women liberty…Freedom of expression is the most important thing in the world, and music is a part of freedom. If we don’t have freedom of expression, how can you genuinely have music?

Khadija Ismayilova — Azerbaijan

Khadija Ismayilova

Ismayilova is an award-winning Azerbaijani journalist, working with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. She is know for her investigative reporting on corruption connected to the country’s president Ilham Aliyev. Azerbaijan has a notoriously poor record on human rights, including press freedom, and Ismayilova has been repeatedly targeted over her work. She was blackmailed with images of an intimate nature of her and her boyfriend, with the message to stop “behaving improperly”. This February, she was taken in for questioning by the general prosecutor several times, accused of handing over state secrets because she had met with visitors from the US Senate. In light of this, she posted a powerful message on her Facebook profile, pleading for international support in the event of he arrest.

WHEN MY CASE IS CONCERNED, if you can, please support by standing for freedom of speech and freedom of privacy in this country as loudly as possible. Otherwise, I rather prefer you not to act at all.

Jillian York — US

Jillian York (Image: Jillian C. York/Twitter)

Jillian York is a writer and activist, and Director of Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). She is a passionate advocate of freedom of expression in the digital age, and has spoken and written extensively on the topic. She is also a fierce critic of the mass surveillance undertaken by the NSA and other governments and government agencies. The EFF was one of the early organisers of The Day We Fight Back, a recent world-wide online campaign calling for new laws to curtail mass surveillance.

Dissent is an essential element to a free society and mass surveillance without due process — whether undertaken by the government of Bahrain, Russia, the US, or anywhere in between — threatens to stifle and smother that dissent, leaving in its wake a populace cowed by fear.

Cao Shunli — China

Cao Shunli (Image: Pablo M. Díez/Twitter)

Shunli is an human rights activist who has long campaigned for the right to increased citizens input into China’s Universal Periodic Review — the UN review of a country’s human rights record — and other human rights reports. Among other things, she took part in a two-month sit-in outside the Foreign Ministry. She has been targeted by authorities on a number of occasions over her activism, including being sent to a labour camp on at least two occasions. In September, she went missing after authorities stopped her from attending a human rights conference in Geneva. Only in October was she formally arrested, and charged for “picking quarrels and promoting troubles”. She has been detained ever since. The latest news is that she is seriously ill, and being denied medical treatment.

The SHRAP [State Human Rights Action Plan, released in 2012] hasn’t reached the UN standard to include vulnerable groups. The SHRAP also has avoided sensitive issue of human rights in China. It is actually to support the suppression of petitions, and to encourage corruption.

Zainab Al Khawaja — Bahrain

Zainab Al Khawaja

Al Khawaja is a Bahraini human rights activist, who is one of the leading figures in the Gulf kingdom’s ongoing pro-democracy movement. She has brought international attention to human rights abuses and repression by the ruling royal family, among other things, through her Twitter account. She has also taken part in a number of protests, once being shot at close range with tear gas. Al Khawaja has been detained several times over the last few years, over “crimes” like allegedly tearing up a photo of King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. She had been in jail for nearly a year when she was released in February, but she still faces trials over charges like “insulting a police officer”. She is the daughter of prominent human rights defender Abdulhadi Al Khawaja, who is currently serving a life sentence.

Being a political prisoner in Bahrain, I try to find a way to fight from within the fortress of the enemy, as Mandela describes it. Not long after I was placed in a cell with fourteen people—two of whom are convicted murderers—I was handed the orange prison uniform. I knew I could not wear the uniform without having to swallow a little of my dignity. Refusing to wear the convicts’ clothes because I have not committed a crime, that was my small version of civil disobedience.

This article was posted on March 8, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

28 Feb 2014 | Awards, News and features

The Colectivo Chuchan is a mental health pressure group campaigning to change the treatment of people within Mexico’s mental health institutions.

Members all have ongoing mental health challenges themselves and most have spent time in institutions. Through their work they give a voice and access to freedom of expression to Los Abandonados, the millions of Mexican people who might otherwise be stuck in institutions with no hope of changing their situations.

Nominees: Advocacy | Arts | Digital Activism | Journalism

Join us 20 March 2014 at the Barbican Centre for the Freedom of Expression Awards

The Colectivo works to convince Mexican government to integrate people with psychiatric disabilities back into their communities, rather than institutionalise them. Encouraged by their own experiences, the Colectivo believe this can be achieved if these people are given support. Executive Director Raúl Montoya Santamaría, for instance, has spoken about mental illness and Colectivo Chuchan at events, conferences, universities and on TV and radio in Mexico – bringing important attention to an issue that might otherwise not be covered.

“Meeting the Colectivo Chuchan had a profound effect on me and they helped to breakdown a lot of my ignorance of psychiatric disability. Their battle to change the attitudes of a nation will be long and arduous; most of them may not be alive to see the transformation. Some of them risk damaging their own mental health for this cause, but they see the human rights of people with psychiatric disabilities as something worth fighting for,” said Ade Apitan, presenter for an Unreported World team covering the tragedy of Mexico’s mental institutions.

This article was originally posted on February 28, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Due to an factual error in the original video, it was replaced by a corrected version on 10 March 2014 at 2.47pm

13 Dec 2013 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Russia

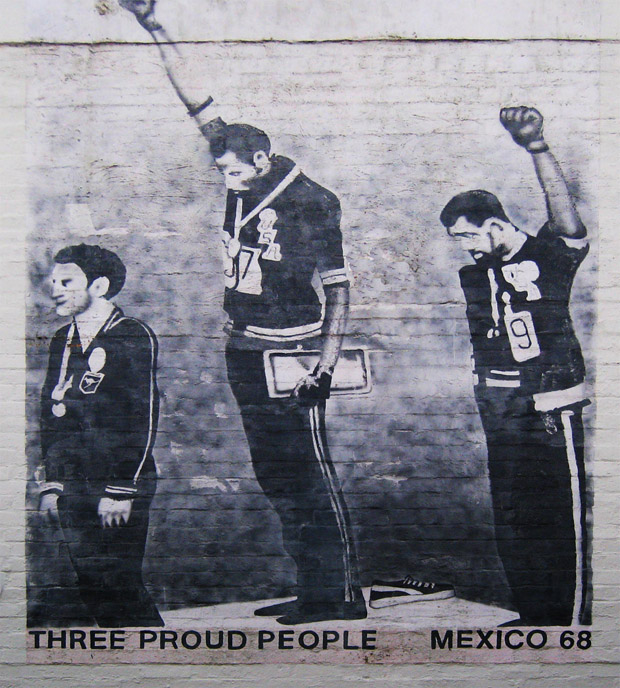

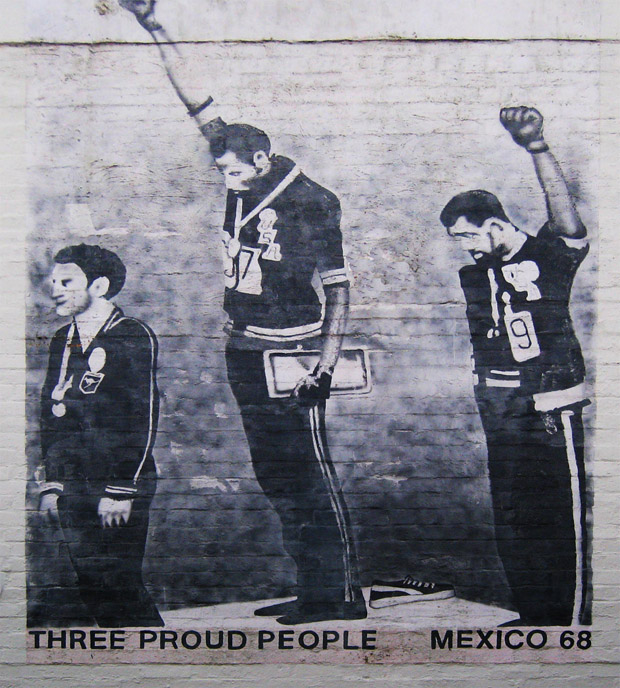

Grafitti of Tommie Smith, John Carlos and Peter Norman showing solidarity for the civil rights movement at the Mexico City Olympics in 1968 (Image: Newtown graffiti/Wikimedia Commons)

Athletes preparing to head off to Sochi Winter Olympics in February, have been reminded that they are barred from making political statements during the games.

”We will give the background of the Rule 50, explaining the interpretation of the Rule 50 to make the athletes aware and to assure them that the athletes will be protected,” said IOC President Thomas Bach in an interview earlier this week. Rule 50 stipulates that ”No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.” Failure to comply could, at worst, mean expulsion for the athlete in question.

Political expression is certainly a hot topic at Sochi 2014. The games continue to be marred by widespread, international criticism of Russia’s human — and particularly LGBT– rights record. The outrage has especially been directed at the country’s recently implemented, draconian anti-gay law. Put place to “protect children”, it bans “gay propaganda”. This vague terminology could technically include anything from a ten meter rainbow flag to a tiny rainbow pin, and there have already been arrests under the new legislation.

The confusion continued as the world wondered how this might impact LGBT athletes and spectators, or those wishing to show solidarity with them. Russian authorities have for instance warned of possible fines for visitors displaying “gay propaganda”. Could this put the Germans, with their colourful official gear, in the firing line? (Disclaimer: team Germany has denied that the outfits were designed as a protest.)

On the other hand, Russian president Vladimir Putin has promised there will be no discrimination at the Olympics, and IOC Chief Jaques Rogge, has said they “have received strong written reassurances from Russia that everyone will be welcome in Sochi regardless of their sexual orientation.”

On top of this, the IOC also recently announced that there will be designated “protest zones” in Sochi, for “people who want to express their opinion or want to demonstrate for or against something,” according to Bach. Where these would be located, or exactly how they would work, was not explained.

But while the legal situation in Russia adds another level of uncertainty and confusion regarding free, political expression for athletes, rule 50 has banned it for years. And for years, athletes have taken a stand anyway.

By far the most famous example came during the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City — American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos, on the podium, black gloved fists raised in solidarity with the ongoing American civil rights movement. The third man on the podium, Australian Peter Norman, showed his support by wearing a badge for the Olympic Project for Human Rights. All three men faced criticism at the time, but the image today stands out as one of the most iconic and powerful pieces of Olympic history.

However, the history of Olympians and political protest goes further back than that. An early example is the refusal of American shotputter Ralph Rose to dip the flag to King Edward VII at the 1908 games in London. It us unknown exactly why he did it, but one theory is that it was an act of solidarity for Irish athletes who had to compete under the British flag, as Rose and others on his team were of Irish descent.

The Cold War years unsurprisingly proved to be a popular time for athletes to put their political views across. When China withdrew from the 1960 Olympics in protest at Taiwan, then recognised by the west as the legitimate China, taking part. The IOC then asked Taiwan not to march under the name ‘Republic of China’. While considering boycotting the games, the Taiwanese delegation instead decided to march into the opening ceremony with a sign reading “under protest”.

The same year as the Smith and Carlos protest, a Czechoslovakian gymnast kept her face down during the Soviet national anthem, in protest at the brutal crackdown of the Prague Spring earlier that year. And that was not the only act of defiance against the Soviet Union. During the controversial 1980 Moscow Olympics, boycotted by a number of countries over the USSR invasion of Afghanistan, the athletes competing also took a stand. The likes of China, Puerto Rico, Denmark, France and the UK marched under the Olympic flag in the opening ceremony, and raised it in the medal ceremonies. After winning gold, and beating a Soviet opponent, Polish high jumper Wladyslaw Kozakieicz also made a now famous, symbolic protest gesture towards the Soviet crowd.

But there are also more recent examples. At Athens 2004, Iranian flyweight judo champion Arash Miresmaeili reportedly ate his way out of his weight category the day before he was set to fight Israeli Ehud Vaks. “Although I have trained for months and was in good shape, I refused to fight my Israeli opponent to sympathise with the suffering of the people of Palestine” he said. A member of the South Korean football team which beat Japan to win bronze at the 2012 London Olympics, celebrated with a flag carrying a slogan supporting South Korean sovereignty over territory Japan also claims.

When the debate on political expression comes up, the argument of “where do we draw the line” often follows. If the IOC is to allow messages of solidarity with Russia’s LGBT population, should they allow, say, a Serbian athlete speak out against Kosovan independence? Or any number of similar, controversial political issues? Is it not easier to simply have a blanket band, and leave it at that?

The problem with this is, as much as the IOC and many other would like it, the Olympics, with all their inherent symbolism, simply cannot be divorced from wider society or politics. The examples above show this. With regards to Sochi in particular, the issue is pretty straightforward — gay are human rights. Some have argued we should boycott a Olympics in a country that doesn’t respect the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, or indeed the Olympic Charter. This is not happening, so the very least we can is use the Olympics to shine a light on gay rights in Russia. At its core, the Olympics are about the athletes — they are the most visible and important people there. It remains to be seen whether any of them will take a stand for gay rights, outside cordoned-off protest areas, in the slopes and on the rink, where the spotlight shines the brightest. And if they do, they should have our full support.

This article was posted on 13 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Nov 2013 | Comment, News and features

Martin O’Hagan, murdered in 2001

Earlier this week, the Northern Ireland Attorney General John Larkin suggested that investigations and prosecutions for violence carried out during “the Troubles” (that is to say, roughly between 1970 and the Good Friday Agreement of 1998) should be quietly dropped.

The idea, though well meaning, was not well received. Northern Ireland is constantly torn between wanting to forget about the past and requiring justice for history’s victims. It’s unlikely that it can have both at the same time.

The peace process did not bring an end to violence, in spite of the official line. Dissenting groups continued shooting and maiming, albeit in lower numbers.

Among them was the Loyalist Volunteer Force, which, in 2001, took the unprecedented-in-Ulster step of assassinating a journalist.

Martin O’Hagan was an investigative reporter for the Sunday World, an old-style tabloid published in Dublin and Belfast that specialises in stories about gangsters and paramilitaries. As a result, he had been harassed by paramilitaries on all sides, including being kidnapped by the provisional IRA. (He himself had been a member of the Official IRA before giving up on the cause and going into journalism)

O’Hagan had a particular interest in the activities of notoriously violent Belfast loyalist Billy Wright, whom he nicknamed “King Rat”. In 1992, Wright, then a member of the Ulster Volunteer Force, had attempted to have O’Hagan killed. Later, Wright’s splinter group, the Loyalist Volunteer Force, had attacked the Sunday World’s Belfast office.

In 1997, Wright, by then in prison, was killed by rival prisoners in the Irish National Liberation Army (questions remain for some over how the INLA managed to sneak a gun into prison).

Four years later, in 2001, O’Hagan was gunned down. The Red Hand Defenders, an operational name for the Loyalist Volunteer Force, claimed responsibility for the murder.

Twelve years later, no one has been convicted for O’Hagan’s murder. There had been hope that a case could be built against murderers based on a Loyalist “supergrass”, Neil Hyde. But in January, prosecutors dropped the case, citing a risk of basing it on uncorroborated evidence. In September, the case was passed to Northern Ireland’s police ombudsman for investigation. Though O’Hagan’s murder falls outside Attorney General Larkin’s proposed timescale for dropping prosecutions, there seems little prospect of a conviction any time soon

On 23 November, journalists mark International Day To End Impunity, highlighting the remarkable, disturbing frequency with which attacks on reporters go unpunished. It’s very easy to imagine that these are things that only happen in Mexico or Putin’s Russia.

But Martin O’Hagan, a good journalist doing his job of uncovering wrongdoing, was killed in the United Kingdom. And his killers, from the United Kingdom, are still free.

This article was originally posted on 22 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org