Sarah Brown: ‘If you can see it, you can be it’

The following speech by Sarah Brown, education campaigner for A World at School, was delivered at the launch event for the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

I am delighted to be at Lilian Baylis Technology School – I went to school in North London, but my first flat was just down the road from here – I know how hard everyone at this school has worked for it become the first in Lambeth to get an outstanding in its Ofsted and now stands out as ‘outstanding in all aspects’ in the top 10% in the country. Being named for a pioneering woman who nurtured some amazing talent in the theatre, opera and ballet worlds leaving her mark across London gives the school a lot to live up to, but clearly nurturing some amazing talent here of its own these days.

Index on Censorship’s magazine that we are launching here tonight also serves to highlight some talented voices, and some very courageous ones too. Like all of the magazine editions which came before it, it is distinguished by both the quality of its writing and the bravery of its stance. But this one is particularly important to me for the priority it has placed on the voices of women. From pioneering feminists writing about women’s safety in India to the stories of female resistance and of hope from the Arab Spring, this magazine is giving a megaphone to the people whose contribution is so often marginalised, ignored, or eliminated altogether.

In the spirit of Index on Censorship’s core values, the power of our voice is the theme of my remarks tonight. And I want to start by updating a feminist slogan that lots of women who have done pioneering work on role models have been using for years now. Their view is ‘if she can see it, she can be it’. In other words, if you have a visible role model you are much more likely to keep fighting to get past all of the hurdles that are still too often put in the way of girls and women, just as they are for people who are disabled, or LGBT or BAME, or hold a forbidden political viewpoint in the harshest of regimes around the world.

‘If you can see it, you can be it’ – I very much think that’s true – the importance of strong visible women role models. Even my own sense of what is possible for me has certainly been determined by watching women – whether my own mother learning and leading throughout her life, from running an infant’s school in the 70’s in the middle of Africa, completing her PhD a few years go in her seventies and even now I am struggling to keep up her as she launches a new project leading the research on a study of quilt-makers (mostly women) and the stories they tell. Other role models from me have ranged from the icons of my teenage years from poet and rock artist Patti Smith to writer Jill Tweedie to American feminist Gloria Steinum. Today my work leads me to meet such a range of inspirational women leaders from Graca Machel to Aung San Suu KyI to President Joyce Banda of MalawI to young women like AshwinI Angadi, born blind in a poor rural community in India she fought for her education, graduated from Bangalore university with outstanding grades, gave up her job in IT to campaign for the rights of people with disabilities, and I find myself alongside at the UN last month.

So I agree that visibility counts, but if I think of my role models they are all women who never give up raising their voices – who make a career literally of speaking up. And I want to update that old slogan with a rather more disturbing thought and suggest tonight that if you can hear her, you will fear her.

Let me explain what I mean.

From Nigeria to Egypt to Yemen and Afghanistan to the richest countries of the West, we are seeing the rise of targeted attacks focused on women who use their voice to speak out for other women. Sometimes these attacks are physical, and I will talk about them more in a moment. But here in the UK there has been a spate of attacks which are verbal and online, and which are perpetrated by men who fear women’s power.

From the disgusting rape threats directed at Caroline Criado-Perez for daring to suggest a woman should remain on British bank notes to the horrendous and sexualised verbal violence meted out to Mary Beard after she appeared on question time to model Katie Piper finding her online voice speaking up for the stigma of disfiguration in a defiant response to the acid attack on her, and the creation of her defiant new beauty at the hands of her NHS surgeon. And of course, the all too prevalent victims of domestic violence who get a collective voice through women’s aid and the main refuges around the UK – who speak up more when they see it can even happen to a goddess like Nigella.

It is clear that the public square – and too often the private home – simply doesn’t provide a safe environment for Britain’s women.

If anybody doubts how bad things have got, I’d encourage you to go and take a look at Laura Bates’ work with the Everyday Sexism Project, an online directory of harassment, discrimination and abuse submitted by over 50,000 women who are shouting back. It paints a picture of a Britain in which violence and the threat of violence against women is so routine, women had almost ceased to notice it as a crime and an outrage, until a platform came along that gave their problem visibility and, with it, importance.

So I want to suggest that a public square which is so hostile to women that they do not feel they can participate in it without inviting overwhelming abuse is, itself, a form of censorship. It might not be the same process as smashing up a newspaper office or burning a book or even shooting teenage girls on a school bus, but the effect is the same: that of silencing a voice which has a right to be heard.

And if you want further evidence of how hearing how women’s voices can terrify those who risk losing their power, just consider how the worst misogynists in the world were afraid of just three words.

The words I’m talking about weren’t said by somebody famous. They weren’t said by somebody powerful. They hadn’t even been planned before they were uttered. But they awoke the world.

Malala YousafzaI as a schoolgirl from rural Pakistan published her youthful diary detailing how life had changed for girls after the Taliban took over her mountain town. She and her friends Shazia and Kainat spent the next few years campaigning for girls to be allowed to return to school, although they knew how dangerous speaking out against the Taliban could be. Malala even talked in interviews about how they might try to kill her for it.

Just over a year ago, this worst imagining happened and Malala was targeted by a Taliban assassin. He boarded the school bus, identified Malala and shot her in the head, and injured Shazia and Kainat sitting either side of her. As the footage of Malala’s airlift to safety was broadcast young women used just three words to claim their solidarity and support with her “I am Malala’. She and her two friends are all now safely in the UK continuing their education, and as the worlds’ gaze has given them some safety the campaign continues with a growing movement of young people all of whom are role models for every child around the world, whether in school or waiting for the dream to come true and the opportunity to learn coming to them too.

It was such a powerful reminder of a question I first asked myself some time ago:

Why is the most terrifying thing for the Taliban a girl with a book? Or for that matter the terrifying group in Nigeria – Boko Haram – who are firebombing schools and dormitories while students sleep. Boko Haram – the name literally means – western education is evil.

These terrorists know, better than we do, that a girl with an education is the most formidable force for freedom in the world. A girl who can read and write and argue can be brutalised and oppressed, she can be bought and sold, discriminated against and denied her rights. But she cannot, in the end, be stopped.

Girls like Malala, Kainat, Shazia and others in the end, will prevail.

And that is why they hate them so.

And so it seems to me if a girl like Malala, on her own, can inspire so much fear, then imagine what she could do if backed by a movement of hundreds of millions. That is why I believe that the efforts to achieve global education are at the heart of how we unlock the potential of every young citizen. As children learn, they achieve understanding, tolerance, opportunity and the chance to contribute to a better world. Reaching girls is at the heart of this – we need to do so much better for girls.

Right now, there are 57 million children missing from school. That’s 57 million of our younger selves missing out on the education which could transform not just their lives, but the world. 31 million are girls, and of those at school, many many millions are not learning, and girls are just not getting the same number of school years as their own brothers – to the detriment of everyone.

New research has shown that providing universal education in developing countries could lift their economic growth rates by up to 2% a year and the results are starkest of all when it comes to educating girls.

All the evidence shows that for every extra year of education you give a girl, you raise her children’s chances of living past five years old, because educated mums are more likely to immunise their kids and get them the health care they need. Educated girls are more likely to stay AIDS-free and are less vulnerable to sexual exploitation by adults. They marry later, have fewer children and are more likely to educate their children in turn. Perhaps most importantly of all, education increases a girl’s chance of well-paid employment in later life and the evidence suggests that female earners are more likely to spend their wages to the benefit of their children and community than traditional male heads of the household.

And the benefits, of course, don’t always stay just on a local community level, but can sometimes have national and even global implications too. Because if you look at women who have been in leading positions in every continent around the world – from Sonia GandhI to Graca Machel to Dilma Rousseff to Joyce Banda, they all have one thing in common. They all have an above average level of education. And that’s why one of my new mantras is women who lead, read.

If we want better politics, a politics of pluralism and freedom of expression around the world, then it begins with empowering women – and that begins with educating them.

So there are plenty of good reasons to invest in education and learning for every child – but the best bit is that we’ve already promised to. We are not advocating for a new pledge, simply for the fulfilment of one already made. In the year 2000 world leaders committed to getting every child in school by 2015 as part of a series of ambitious targets called the millennium development goals. World leaders have already signed the contract, now they just need to deliver the goods.

So for me the argument about whether we should invest in education to get the 57 children missing from school into the classroom is a bit of a no brainer – and for me there is no question that closing the gender gap in education should be the priority. As soon as people hear the facts, they tend to stop asking whether we should do it and start to focus on whether we can.

That’s a fair question and people will always want to probe whether we can make a difference to decisions taken hundreds of thousands of miles away. It’s a question I ask myself a lot too. But I take heart from two things. Firstly, we know that progress is possible even on seemingly very big problems because we have made it before. You can look at the big changes in the last century or so – from the end of slavery, achieving the vote for women, the end of apartheid – all started as impossible calls for change, but change came. Enough voices gathered together calling for the same thing – even a politician can’t fail to hear the call then, or if minded to change anyway can do so with a strong mandate behind him or her. Even campaigns I have contributed- that we may all have contribute to – from drop the debt to make poverty history to the maternal mortality campaign brought big changes – but I have heard first-hand what happens at the start – “it is too big an ask, it can’t be done in the time, it is too costly” – well enough free voices calling for action and – give it a little bit of time and a whole lot of noise – change comes. Less than ten years ago over 500,000 women were dying in pregnancy and childbirth unwitnessed, unacknowledged unnoticed by political leaders who held the power to save these lives. Today thanks to the collective voices of those who cared enough – through the white ribbon alliance and others, that number is a whopping 47% lower, and the work to reduce it further continues at the highest levels, and out in the more remote rural areas where the message needs to be carried far and wide to reach every woman at risk.

A 47% drop in the number of mothers dying. That’s not just a number – that means there are thousands of dads living with the love of their lives when they would otherwise have a broken heart nobody else could possibly mend. Thousands of big brothers and sisters who didn’t need to fear that in gaining a new member of the family they risked losing an old one. And thousands of babies being nursed to sleep tonight by the person who loves them most in the world and who has survived to love them as they grow. So this stuff works: campaigning is the key for all of us lucky enough to use our voices.

And on education, I am hopeful we can get even further than we have with the maternal mortality campaign, and achieve all of our goals by 2015. I know that sounds incredibly ambitious – because it means getting 57 million children into school in less than two years. Gordon and I have decided to devote the next years of our lives to this and we intend to be judged by our results. Increasing awareness is great – but if the numbers of children getting a high quality education does not increase in leaps and bounds in the years to come then we collectively will have failed.

Thankfully, we have a lot of help. When Gordon was appointed the United Nations’ Secretary General’s Special Envoy on education, the weight of the UN system was added to our cause. Business leaders have come on board to the Global Business Coalition for Education that I am fortunate to chair, and I am pleased that religious leaders have agreed to form a faith coalition to mobilise the faith communities as has happened so powerfully for debt relief and make poverty history in the past. Most significantly, younger people are lining up at as ambassadors, spokespersons, online champions and community mobilisers – the 600 strong youth leaders from the digital platform A World at School who assembled at the un on Malala Day in July, are all now engaging with their networks, supported by NGOs from around the world. The digital platform is growing rapidly, and the consistent messages, the constant call for action and the rising volume are starting to make a difference. From Syrian refugee children needing a place at school this autumn to young girls wanting to study before they marry in Yemen, Nigeria, Bangladesh to child workers who have never been inside a classroom, the momentum for them is growing.

This grand confluence of forces is powered by the single most important driver of change – every individual who cares enough to take up an action – whether just a tweet or post, or more. It includes you.

Because if we can’t mobilise millions of so-called ordinary people to do hundreds of extraordinary things, the governments of the world will conclude that the pledge they made to get every child into school can be allowed to quietly slip away, the pledge for gender equality ignored, the pledge that every child can be safe from violence, from trafficking and from finding their own voice just disappears. That would be a tragedy not just for the millions of children whose lives continue to be destroyed, but for the notion of progress itself.

If we can’t even rely on our leaders to do that which they have promised to do, can we rely on them to do all that we need them to do? I don’t want my children to grow up in a generation of cynics, a whole group of people who think that promises don’t get kept and politics doesn’t really work. I want them to see and to know that if we make a promise – particularly a promise to a child – we keep it. That when we see an injustice, we right it. That when we are presented with an opportunity we seize it. And that when we have the chance to change the world there is nothing we won’t do to see that potential fulfilled.

That, for me, is the ambitious spirit of activism which Index on Censorship embodies, and the one which we must now bring to bear in ensuring that the girls and women of the world learn first how to read, and then how to lead. This is the chance of our generation and I hope you, like me, think it is one we must grasp with both hands.

This speech transcript was originally posted on 18 Oct, 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

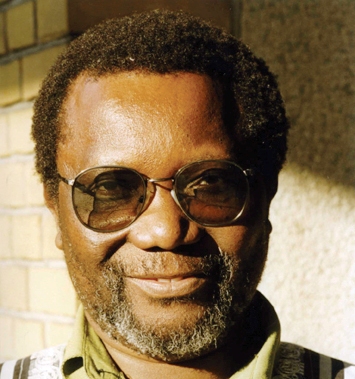

Born in Malawi in 1944, Jack Mapanje, one of Africa’s most distinguished poets, studied in England before returning to teach at the University of

Born in Malawi in 1944, Jack Mapanje, one of Africa’s most distinguished poets, studied in England before returning to teach at the University of