Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Index on Censorship is deeply concerned by these proposals, which are likely to be used to stifle criticism of the government.

“Around the world from Cuba to Indonesia and Uganda, artists are being pressured by governments seeking to control their art and their message. These misplaced efforts are an intolerable intrusion into artistic freedom and must not be enacted,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index said.

Signatories to the letter include U2’s Bono and Adam Clayton, author Wole Soyinka, and Razorlight’s Johnny Borrell.

Full text of the letter follows:

Uganda’s government is proposing regulations that include vetting new songs, videos and film scripts, prior to their release. Musicians, producers, promoters, filmmakers and all other artists will also have to register with the government and obtain a licence that can be revoked for a range of violations.

We, the undersigned, are deeply concerned by these proposals, which are likely to be used to stifle criticism of the government.

We, the undersigned, vehemently oppose the draconian legislation currently being prepared by the Ugandan government that will curtail the freedom of expression in the creative arts of all musicians, producers and filmmakers in the country.

The planned legislation includes:

Contained in a 14 page draft Bill that bypasses Parliament and will come before Cabinet alone in March to be passed into law, any artist, producer or promoter who is considered to be in breach of its guidelines shall have his/her certificate revoked.

This proposed legislation is in direct contravention of Clause 29 1a b of the Ugandan

Constitution which states:

assembly and association.

(1) Every person shall have the right to—

(a) Freedom of speech and expression which shall include freedom of the media;

(b) Freedom of thought, conscience and belief which shall include academic

freedom in institutions of learning;

Furthermore, in accordance with Clause 40 (2)

(2) Every person in Uganda has the right to practise his or her profession and to

carry on any lawful occupation, trade or business.

As a Member State of the African Union, the Republic of Uganda has ratified the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Article 9 of the Charter provides:

We therefore call upon the Ugandan government to end this grievous and blatant

violation of the constitutional rights of Ugandan artists and producers, and to honour

its international obligations as laid down in the various international human rights

conventions to which Uganda is a signatory and for Uganda to uphold freedom of speech.

Background

ABTEX – Producer, Uganda

ADAM CLAYTON – Musician, U2

ALEX SOBEL – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

AMY TAN – Novelist, Screenwriter

ANDY HEINTZ – Freelance journalist and author, USA

ANISH KAPOOR – Artist, United Kingdom

ANN ADEKE – Member of Parliament, Uganda

ANNU PALAKUNNATHU MATTHEW – Artist, USA and India

ASUMAN BASALIRWA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

AYELET WALDMAN – Writer

BELINDA ATIM – Uganda Sustainable Development Initiative

BILL SHIPSEY – Founder, Art for Amnesty

BONO – Musician, U2

BRIAN ENO – Artist, Musician and Producer

BRUCE ANDERSON – Journalist Editor/Publisher

CLAUDIO CAMBON – Artist/Translator, France

CRISPIN BLUNT – Member of Parliament and former Chair of Foreign Affairs Select Committee, United Kingdom

DAN MAGIC – Producer, Uganda

DANIEL HANDLER – Writer, Musician aka Lemony Snicket

DAVID FLOWER – Director, Sasa Music

DAVID HARE – Playwright

DAVID SANCHEZ – Saxophonist and Grammy Winner

DEBORAH BRUGUERA – Activist, Italy

DELE SOSIMI – Musician – The Afrobeat Orchestra

DOCTOR HILDERMAN – Artist, Uganda

DR VINCENT MAGOMBE – Journalist and Broadcaster

DR PAUL WILLIAMS – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

EDDIE HATITYE – Director, Music In Africa

EDDY KENZO – Artist, Uganda

EDWARD SIMON – Musician and Composer, Venezuela

EFE OMOROGBE – Director Hypertek, Nigeria

ERIAS LUKWAGO – Lord Mayor of Kampala Uganda

ELYSE PIGNOLET – Visual Artist, USA

ERIC HARLAND – Musician

FEMI ANIKULAPO KUTI – Musician, Nigeria

FEMI FALANA – Human Rights Lawyer, Nigeria

FRANCIS ZAAKE – Member of Parliament, Uganda

FRANK RYNNE – Senior Lecturer British Studies, UCP, France

GARY LUCAS – Musician

GERALD KARUHANGA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

GINNY SUSS – Manager, Producer

HELEN EPSTEIN – Professor of Journalism Bard College

HENRY LOUIS GATES – Director of the Hutchins Center at Harvard University

HUGH CORNWELL – Musician

IAIN NEWTON – Marketing Consultant

INNOCENT (2BABA) IDIBIA – Artist, Nigeria

IRENE NAMATOVU – Artist, Uganda

IRENE NTALE – Artist, Uganda

JANE CORNWELL – Journalist

JEFFREY KOENIG – Partner, Serling Rooks Hunter McKoy Worob & Averill LLP

JESSE RIBOT – American University School of International Service

JIM GOLDBERG – Photographer, Professor Emeritus at California College of the Arts

JODIE GINSBERG – CEO, Index on Censorship

JOEL SSENYONYI – Journalist, Uganda

JON FAWCETT – Cultural Events Producer

JON SACK – Artist

JOHN AJAH – CEO, Spinlet

JOHN CARRUTHERS – Music Executive

JOHN GROGAN – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

JONATHAN LETHEM – Novelist

JONATHAN MOSCONE – Theater Director

JONATHAN PATTINSON – Co-Founder Reluctantly Brave

JOHNNY BORRELL – Singer, Razorlight

JOJO MEYER – Musician

KADIALY KOUYATE – Musician, Senegal

KALUNDI SERUMAGA – Former Director – Uganda National Cultural Centre/National Theatre

KASIANO WADRI – Member of Parliament, Uganda

KEITH RICHARDS OBE – Writer

KEMIYONDO COUTINHO – Filmmaker, Uganda

KENNETH OLUMUYIWA THARP CBE – Director The Africa Centre

KING SAHA – Artist, Uganda

KWEKU MANDELA – Filmmaker

LAUREN ROTH DE WOLF – Music Manager Orchestra of Syrian Musicians

LEMI GHARIOKWU – Visual Artist, Nigeria

LEO ABRAHAMS – Producer, Musician, Composer

LES CLAYPOOL – Musician, Primus

LINDA HANN – MD Linda Hann Consulting Group

LUCIE MASSEY – Creative Producer

LUCY DURAN – Professor of Music at SOAS University of London

LYNDALL STEIN – Activist/Campaigner, United Kingdom

MARC RIBOT – Musician

MARCUS DRAVS – Producer

MAREK FUCHS – MD Sauti Sol Entertainment, Kenya

MARGARET ATWOOD – Author

MARK LEVINE – Professor of History UC Irvine – Grammy winning artist

MARY GLINDON – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

MATT PENMAN – Musician, New Zealand

MARTIN GOLDSCHMIDT – Chairman, Cooking Vinyl Group

MEDARD SSEGONA – Member of Parliament, Uganda

MICHAEL CHABON – Writer

MICHAEL LEUFFEN – NTS Host, Carhartt WIP Music Rep

MICHAEL UWEDEMEDIMO – Director, CMAP and Research Fellow King’s College London

MILTON ALLIMADI – Publisher, The Black Star News

MORGAN MARGOLIS – President, Knitting Factory Entertainment, USA

MOUSTAPHA DIOP – Musician, Senegal MusikBi CEO

MR EAZI – Musician, Producer, Nigeria

MUWANGA KIVUMBI – Member of Parliament, Uganda

NAOMI WEBB – Executive Director, Good Chance Theatre, United Kingdom

NICK GOLD – Owner, World Circuit Records

NUBIAN LI – Artist, Uganda

OHAL GRIETZER – Composer

OBED CALVAIRE – Musician

OMOYELE SOWORE – Founder Sahara Reporters and Nigerian Presidential Candidate

PATRICK GRADY – Member of Parliament, United Kingdom

PAUL MAHEKE – Artist, United Kingdom

PAUL MWIRU – Member of Parliament, Uganda

PETER GABRIEL – Musician

RACHEL SPENCE – Arts Writer and Poet, United Kingdom

RASHEED ARAEEN – Artist, United Kingdom

RAYMOND MUJUNI – Journalist, Uganda

RHETT MILLER – Musician, Writer

RILIWAN SALAM – Artist Manager

ROBERT MAILER ANDERSON – Writer and Producer

ROBIN DENSELOW – Journalist, United Kingdom

ROBIN EUBANKS – Trombonist, Composer, Educator

ROBIN RIMBAUD – Musician

RUTH DANIEL – CEO, In Place of War

SAMIRA BIN SHARIFU – DJ

SANDOW BIRK – Visual Artist, USA

SANDRA IZSADORE – Author, Artist, Activist, USA

SEAN JONES – Musician, Composer, Bandleader, Educator

SEBASTIAN ROCHFORD – Musician, Pola Bear

SEUN ANIKULAPO KUTI – Musician, Composer

SHAHIDUL ALAM – Photojournalist and Activist, Bangladesh

SIDNEY SULE – B.A.H.D Guys Entertainment Management, Nigeria

SIMON WOLF – Senior Associate, Amsterdam & Partners LLP

SRIRAK PLIPAT – Executive Director, Freemuse

STEPHEN BUDD – OneFest / Stephen Budd Music Ltd

SOFIA KARIM – Architect and Artist

STEPHEN HENDEL – Kalakuta Sunrise LLC

STEVE JONES – Musician and Producer

SUZANNE NOSSEL – CEO, PEN America

TANIA BRUGUERA – Artist and Activist, Cuba

TOM CAIRNES – Co-Founder Freetown Music Festival

WOLE SOYINKA – Nobel Laureate, Nigeria

YENI ANIKULAPO KUTI – Co-Executor of the Fela Anikulapo Kuti Estate

ZENA WHITE – MD, Knitting Factory and Partisan Records

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Crime writers have less to lose than travel writers in describing the underside of holiday spots, argues Rachael Jolley in the summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_single_image image=”101057″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The results are stark. Many top tourism destinations do terribly on freedom of expression.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The other side: Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia was murdered on 16 October 2017

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Trouble in paradise” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F06%2Ftrouble-in-paradise%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes a special look at how holidaymakers’ images of palm-fringed beaches and crystal clear waters contrast with the reality of freedoms under threat

With: Ian Rankin, Victoria Hislop, Maria Ressa [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”100776″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/06/trouble-in-paradise/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

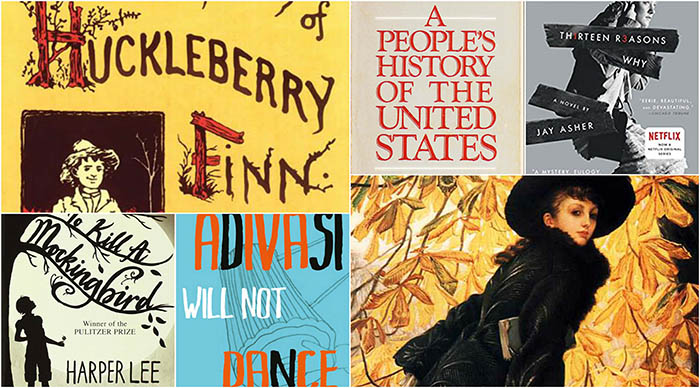

An annual celebration of the freedom to read, Banned Books Week was launched in 1982 in response to a surge in book censorship in schools, bookshops and libraries in the USA.

Since then, over 11,300 books have been banned. Thankfully, there have always been those committed to challenging censorship, including authors, librarians, teachers and students.

But what are the censors so afraid of? Here are 10 books banned in some way over the last year to give us an idea.

The Netflix adaption of Jay Asher’s young adult novel 13 Reasons Why has been causing controversy over its exploration of teenage suicide ever since its release in March 2017. So much so that New Zealand’s classifications body created a whole new category of censorship, RP18, to restrict the showing of the series to anyone under the age of 18.

Naturally, the treatment of the book itself has followed suit, with many calling for the book to be banned over its perceived irresponsible or unrealistic handling of issues of mental health.

An official Mesa County Valley School District in Colorado, USA, briefly ordered librarians to pull 13 Reasons Why from school bookshelves in April 2017. However, after the intervention of a number of librarians, the curriculum director for the district reversed her decision.

In May 2017, US Republican senator Kim Hendren of Arkansas introduced a bill to ban the works of the late social activists and Boston University professor Howard Zinn from public schools.

Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, which is part of many school and college curriculums across the country, is an attempt to bring to light parts of US history that aren’t covered in-depth elsewhere, including equality movements throughout the 20th century.

Many US conservatives argue that there is already too much focus on race and class, including slavery and the genocide of Native Americans, in school curriculums. Bills such as Hendren’s — and that of an Oklahoma lawmaker in 2015 which sought to correct the fact that the USA was not portrayed in a positive enough light in history curriculums — are intended to redress the situation.

However, Hendren’s bill has only increased demand for the works of Zinn. Some 700 copies of A People’s History of the United States were sent free to teachers and librarians throughout Arkansas thanks to the controversy and thanks to a flood of donations copies are being given away to any middle or high school teacher or librarian in Arkansas who asks.

In December 2016, a US school district has banned To Kill a Mockingbird and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn after a parent complained about use of racist language. The books were removed from classrooms and school libraries in Accomack County, Virginia.

It came after one parent told a school board meeting: “I’m not disputing this is great literature, but there is so much racial slurs in there and offensive wording that you can’t get past that, and right now we are a nation divided as it is.”

Racism is a central theme in Mark Twain’s classic work, which explores the oppression of black slaves in pre-Civil War America. It includes the word “nigger” over 200 times. But it is a satire which tackles racism with irony and many fans of the book would agree that is, in fact, a great anti-racist novel. Which is why so many were dismayed in 2011 when a new edition of Huckleberry Finn was released with all uses of the offending word removed.

Likewise, the treatment of To Kill a Mockingbird seemed to be more motivated by the words characters use rather than its critique of racism.

Along with thinking of the children, protecting the dignity of women has always been a mainstay of the moralists. In 1928 all of Chicago’s public libraries removed the Wizard of Oz for “depicting women in strong leadership roles”. Such attitudes are not a thing of the past.

In August of this year, the Jharkhand government in eastern India banned The Adivasi Will Not Dance, a collection of short stories by the award-winning Indian writer Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, for daring to depict women from the Santhal tribe in a sexual way.

Authorities, claiming that the content of the book may disturb law and order situation in Jharkhand, began seizing copies and the author, a government doctor, was suspended from his position.

Shekhar vowed not to edit a single word and advised all who have a problem with it to take the time to actually read it.

Sexual content has been the number one reason for the banning of books this century, and just because a book wasn’t written in this century, doesn’t mean it escapes the censor’s pen.

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, more widely known as Fanny Hill, an erotic novel first published in London in 1748, has been peeving off puritans since it was first printed. While it doesn’t contain a single rude word, John Cleland’s work is about a sex worker who enjoys her work.

For this, the author was prosecuted for “corrupting the king’s subjects”. The book is one of the most banned in history, and in August 2017, a professor at Royal Holloway, University of London, Judith Hawley, said she would worry about upsetting students by teaching the work. Many in the media have accused Hawley of banning the book outright, some saying she removed it from a reading list, but she claims she hasn’t as it was never on the course in the first place. But when is a ban a ban? Speaking on BBC Radio 4, Hawley said of the book: “I use it less than I used to. In the 1980s I both protested against the opening of a sex shop in Cambridge and taught Fanny Hill. Nowadays I’d be afraid of causing offence to my students.” She also raised concerns that her “students would slap me with a trigger warning”. Not teaching something for fear of offending students or to avoid becoming a trigger warning does amount to a ban.

“We shouldn’t assume that pornography is really speaking about sex, or that the only way to speak about sex is pornography,” she later added, but then expressed her worry at the “pornification of modern culture”.

Unless a book contains strictly conventional values and conduct, it has probably irked someone in a position of power somewhere along the way. Unfortunately, this means if you write a book called Gay Soldier’s Diary, you’re likely to to face trouble.

This was the case at the Hong Kong Book fair in July, where several titles, including Gay Soldier’s Diary, were banned on the grounds that they were “indecent”. The books depict no violence or nudity, so don’t actually breach the fair’s rules on indecency, but this didn’t stop organisers removing nine of 15 titles at the Taiwan Indie Publishers Alliance stall, including A Gentleman’s Wedding and Crying Girls.

In 1988, when official censorship ceased in the Soviet Union, banned publications suddenly became easily accessible to the general public. Works by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Leon Trotsky and even Henry Kissinger, which were critical of the Soviet Union or deemed in some way to be subversive.

Whenever the vaults in China finally open, Chinese citizens will find curiosities like Winnie the Pooh, English writer AA Milne’s children’s series.

Pooh Bear’s only crime was to resemble China’s current president Xi Jinping, which some Chinese dissidents were only too eager to point out. Memes that went viral included a 2013 photo of a meeting between Xi and then-US president Barack Obama alongside a picture of Winnie the Pooh and his friend Tigger. As a result, the Chinese name for Winnie the Pooh (Little Bear Winnie) is blocked on Chinese social media sites and those who write”Little Bear Winnie” on the site Weibo are met with an error message.

G25 is a group of 25 Malay-Muslim leaders whose goal is to preserve the basic rights of freedom of expression and worship in Malaysia, where Islam is the official religion.

A book by the group, Breaking the Silence: Voices of Moderation – Islam in a Constitutional Democracy, has been banned after the Malaysian government deemed it to be “prejudicial to public order”. According to G25’s Noor Griffin, “it is meant to encourage debates about the Islamic religion”.

Deputy prime minister Ahmad Zahid Hamidi authorised the ban on the book on 14 June.

In 2014, a comic called Ultraman was banned in the country because it referred to the hero as “Allah”.

Challenges to Bill Cosby’s Little Bill children’s book series followed allegations of sexual assault were made against the comedian by a number of women, reaching back over many years. The censoring of Little Bill books is believed to the first time a title has been targeted solely for its author and not its content, ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom Director James LaRue said.

This article was updated on 28 September to add more context to Judith Hawley’s views on Fanny Hill.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”2″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1506589920727-40713b18-3658-2″ taxonomies=”8820, 6696″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Credit: Kennedy Library

Monday marked the beginning of Banned Books Week. To celebrate the freedom to read, Index on Censorship staff explore some of their favourite, and some of the most important, banned or challenged books.

Ryan McChrystal – Borstal Boy by Brendan Behan

Brendan Behan’s autobiographical work Borstal Boy was banned in Ireland in December 1958. His London publisher, Hutchinson’s, had sent a batch of copies to Dublin to be sold at a Christmas market but they were confiscated at the port. Behan was outraged that a group of “country yobs” could prevent the distribution of his book.

Borstal Boy is the story of how a 16-year-old Behan landed himself in a series of institutions for young offenders in Kent, having been charged with membership of the IRA, and what happened to him after that.

Although Ireland’s Censorship of Publications Board never explained why the book was banned, it probably had something to do with its depictions of adolescents talking about sex and its pillorying of Irish social attitudes, republicanism and the Catholic Church. The board is, after all, known for its stringent adherence to Roman Catholic values.

When Behan later learned that the book was also banned in Australia and New Zealand, he took solace in song and humour as he went around Dublin singing:

“My name is Brendan Behan, I’m the latest of the banned

Although we’re small in numbers we’re the best banned in the land,

We’re read at wakes and weddin’s and in every parish hall,

And under library counters sure you’ll have no trouble at all.”

David Heinemann – From Dictatorship to Democracy by Gene Sharp

Running the Freedom of Expression Awards’ Fellowship and helping brave people who are often fighting totalitarian regimes can sometimes feel like an uphill battle. How can one person or organisation ever hope to defeat an entire dictatorship?

They can’t, of course, but Gene Sharp’s little book reminds me that “the deliberate, non-violent disintegration of dictatorships” is possible when people work together in certain ways. Part handbook, part political pamphlet, it’s an invaluable toolbox for any serious democratic activist. Its potency was illustrated last year when a group of young Angolans were imprisoned simply for trying to get together and discuss it at a book club.

The fact that I could read it on my commute home reminded me never to take my freedoms for granted.

Vicky Baker – The Bible

The Bible is not an obvious choice for me as I’m an atheist, but loosely picking up on that misattributed Voltaire quote, I would defend anyone’s right to read it – or indeed any other religious book.

Pope Francis has called The Bible “an extremely dangerous book”. Owning it or reading it can get you still get you imprisoned or killed in certain parts of the world. This is the sort of book banning that we should all be extremely worried about, whatever your religion.

These days I don’t even have a copy in my house, but its stories formed part of my childhood. When I grew up I learnt that my hometown, Amersham in Buckinghamshire, also had an important connection to censorship of The Bible. In the 16th century a group of local Lollards were burned at the stake for wanting to translate the book from Latin to English; some of their children were forced to light the pyre.

Known as the Amersham Martyrs, they have since been honoured in a memorial stone, costumed walking tours, and through occasional community plays about their lives, staged in a local church. (Imagine if the bishop who sentenced them saw this today.)

Sadly, we live in a world where censorship of the Bible is not ancient history. In 2014, an American man was sent to labour camp in North Korea for leaving a Bible in a restaurant’s bathroom when visiting as a tourist. It was deemed a crazy act – and, indeed, the move also endangered his local tour guides – but it is outrageous that simply leaving a book behind, so readers can choose to pick it up or not, can still lead to such punishments.

David Sewell – The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

One of those cases in the USA where the pressure to ban comes not from the authorities, but from citizens wanting it pulled from libraries or schools. Complaints were made about its sweary language and its graphic depictions of violence and death. But there again it’s about a grunt’s eye view of the Vietnam war, so go figure.

Only this is really a remarkable work of fiction, which is highly literary in its narrative form. It uses stories to try and construct the extreme experience of war, but also uses war to explore the drive to create stories for ourselves. Language is used to defang terror on the battlefield, stories are invented (and embellished through the re-telling) to keep dead comrades alive, because if they are allowed to die, then it brings death one step closer to the surviving soldiers.

A fascinating book that tries to put words to the unsayable and unspeakable, and its would-be censors are attempting to make it a different kind of unspeakable and unsayable.

Kieran Etoria-King – Riotous Assembly by Tom Sharpe

One of the most enduring, darkly funny things I’ve ever read was the opening chapter of Tom Sharpe’s 1971 novel Riotous Assembly, in which a South African police chief argues with an old white woman who shot her black chef in the garden of her stately home. As two deputies collect up the obliterated corpse of the man she killed with a four-barrelled elephant gun, Miss Hazelstone, who graphically describes her illicit love affair with the chef, demands to be arrested for murder, while a disgusted Kommandant van Heerden insists that the killing of a black person is not murder. Meanwhile, the entire police force of the fictional town of Piemburg, operating under mistaken intelligence, are engaged in a fierce and escalating firefight at the gate, unaware that they are actually shooting at each other from behind cover.

Sharpe had lived in South Africa from 1951 to 1961 before he was deported over a play he staged that criticised the government, so he had an intimate knowledge of the country and Riotous Assembly, a hilarious send-up of the South African police force, is driven as much by real venom and contempt for the Apartheid system as it is by vulgar humour. Of course, that system wasn’t going to tolerate such mockery and the book was banned in South Africa as well as Zimbabwe.

Helen Galliano – The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

I first came across The Master and Margarita – considered to be one of the finest novels to come out of the Soviet Union – as a performance student at Goldsmiths and a lover of magical realism. I immediately fell into Bulgakov’s wild and dangerous world of talking cats, decapitations, magic shows, Satan’s midnight ball and plenty of vodka. I was hooked, reading it multiple times throughout my third year and even created a performance reimagining Margarita’s transformation into a witch.

The forward to the 1997 translation of the novel reads: “Mikhail Bulgakov worked on this luminous book throughout one of the darkest decades of the century. His last revisions were dictated to his wife a few weeks before his death in 1940 at the age of forty-nine. For him, there was never any question of publishing the novel. The mere existence of the manuscript, had it come to the knowledge of Stalin’s police, would almost certainly have led to the permanent disappearance of its author.”

Faced with persecution, Bulgakov burned the first manuscript of The Master and Margarita, only to re-write it later from memory. It was eventually published nearly three decades after his death and since then “manuscripts don’t burn”, a famous line from the book, has come to symbolise the power and determination of human creativity against oppression.

Great literature and great ideas will always survive.

What’s it like to be an author of a banned or challenged book? How can librarians support authors who find themselves in this situation? To mark Banned Books Week, Vicky Baker, deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine, will chair an online discussion with three authors on 29 September, followed by a Q&A. It is free to join, although attendees must register in advance.