Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

November is a month of historical anniversaries. Last Thursday was the annual commemoration of the foiling of the Gunpowder Plot and yesterday the UK fell silent to pay tribute to its war dead on Remembrance Sunday.

A much lesser-known date — at least to anyone outside Azerbaijan — is the country’s Flag Day, the celebration of the tricolour which was first adopted as the national flag on 9 November 1918.

The flag hoisted in the capital city of Baku was once confirmed by the Guinness Book of Records as being the tallest in the world. It flies on a pole 162 meters high and measures 70 by 35 meters. While the flag underwent a hiatus while Azerbaijan was part of the Soviet Union between 1920 and 1991, it is now a proud symbol of the country’s independence.

The tricolour consists of three horizontal stripes, each being deeply symbolic. The blue stripe stands for the Turkish origin of Azerbaijani people and the green stripe at the bottom expresses affiliation to Islam. Neither can be disputed. The red stripe in the middle, however, is problematic. It stands for progress, modernisation and democracy.

But Azerbaijan’s status as a modern democracy is less than convincing. Sure, the country has made some significant strides since the collapse of communism. It boasts a 98.8% literacy rate, and since the early 2000s spending on education has increased five-fold, for example.

However, there is an illusion of material progress in Azerbaijan. As Index on Censorship has been reporting, the country has experienced an unprecedented crackdown on human rights and freedoms.

Little over a week ago, Azerbaijan held a parliamentary election while an estimated 20 prisoners of conscience sat in prison. Azerbaijani journalist Khadija Ismayilova, who was sentenced to seven years and six months in jail in September for exposing state corruption, is one of them. The award-winning journalist was detained on 5 December 2014 and eventually convicted of libel, tax evasion and illegal business activity.

President Ilham Aliyev’s government has long claimed that “all freedoms are guaranteed in Azerbaijan“. Given his government’s lack tolerance for dissent, this clearly isn’t the case. Leyla Yunus, founder and director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, and her husband, historian Arif Yunus — both outspoken critics of the government — have been detained since summer 2014 when they were arrested on charges of treason and fraud. On 13 August, the Baku Court on Grave Crimes sentenced Leyla to eight years and six months in prison and Arif to seven years in prison.

Democracy activist Rasul Jafarov, human rights lawyer Intigam Aliyev and journalist Seymur Hezi are also serving prison sentences on charges that were widely condemned for being politically motivated to silence outspoken critics of the government of President Aliyev.

The list of journalists and activists who have been arrested, abused, beaten and even killed goes on. In June 2015, on the eve of the inaugural European Games in Baku, activists from Amnesty International and Platform were banned from entering the country. Both organisations have been highly critical of Aliyev’s government, and its continuing targeting, jailing and prosecution dissenters. Even The Guardian was blocked from reporting on the games when its reporter was barred.

The ruling party in Azerbaijan may have won an outright majority in this month’s elections, cementing Aliyev’s hold on power. However, opposition parties boycotted the vote over concerns it was neither free nor fair. Even the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) refused to monitor the election after authorities severely limited its ability to observe the vote effectively. It marks the first time since 1991 that the OSCE has not monitored an Azerbaijani election and highlights that the situation in the country is far from progressive.

Flag Day is set against a backdrop of arrests and human rights abuses. If Azerbaijan is to earn its stripes, the authorities must uphold their human rights obligations, release all prisoners of conscience and allow for elections that meet basic democratic standards.

This article was posted on 9 November 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Shamsi Badalbayli Street, Baku, 2 April 2012. A resident is forcibly evicted from the area where the Winter Garden will be constructed. Approximately 300 complaints have been sent to the European Court of Human Rights related to forced evictions from this area. This photograph by Ahmed Mukhtar appeared in the autumn 2013 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and was featured at a 2013 exhibition at the ICA.

Freelance journalist Ahmed Mukhtar, a contributor to Index on Censorship magazine, was detained at 7pm Friday 18 September in Azerbaijan, according to Contact.az.

Mukhtar’s brother, Elnur, works with Berlin-based Meydan.TV. His detention is the latest in a string of arrests of family members of contributors to Meydan.tv

“Ahmed Mukhtar is an extremely talented and courageous Azerbaijani photojournalist, whom I’ve had the pleasure of collaborating with through the Art for Democracy campaign. He is one of very few left in the country willing to capture risky subject matter like human rights abuses. His detention comes just one day after the detention of another young journalist, Abbas Shirin, also known for his photography, including his coverage of the recent trials of human rights defenders Leyla and Arif Yunus and journalist Khadija Ismayilova. Now it seems that even photographing people the Azerbaijani authorities have previously targeted is enough to land someone in jail”, said Rebecca Vincent, coordinator of the Sport for Rights campaign and former advocacy director of Art for Democracy, a creative campaign that ceased operations in August 2014 when authorities arrested its coordinator, human rights defender Rasul Jafarov.

Mukhtar was later released, according to a tweet from Vincent.

Update: #Azerbaijan photojournalist Ahmed Mukhtar has been released.

— Rebecca Vincent (@rebecca_vincent) September 18, 2015

Over the weekend, founder of Meydan.TV Emin Milli reported that three more journalists were detained and questioned before being released.

3 Journalists cooperating with @MeydanTV has been just detained in the airport + taken to police station #Azerbaijan pic.twitter.com/cDuZR7ZfM8

— Emin Milli (@eminmilli) September 19, 2015

On Thursday 17 September, Meydan.tv contributor Shirin Abbasov was sentenced to 30 days in jail “for disobeying the police after nearly thirty hours in custody,” according to Meydan.tv.

The Sport for Rights Coalition condemned Azerbaijan’s moves against journalists and independent media.

This article was updated on 21 September.

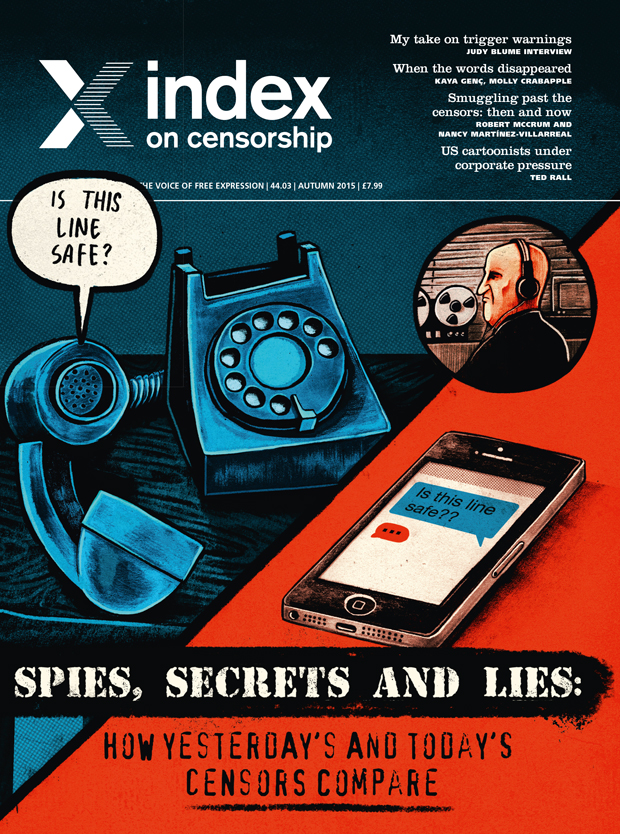

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

Post-Soviet Union, after the fall of the Berlin wall, after the Bosnian war of the 1990s, and after South Africa’s apartheid, the world’s mood was positive. Censorship was out, and freedom was in.

But in the world of the new censors, governments continue to try to keep their critics in check, applying pressure in all its varied forms. Threatening, cajoling and propaganda are on one side of the corridor, while spying and censorship are on the other side at the Ministry of Silence. Old tactics, new techniques.

While advances in technology – the arrival and growth of email, the wider spread of the web, and access to computers – have aided individuals trying to avoid censorship, they have also offered more power to the authorities.

There are some clear examples to suggest that governments are making sure technology is on their side. The Chinese government has just introduced a new national security law to aid closer control of internet use. Virtual private networks have been used by citizens for years as tunnels through the Chinese government’s Great Firewall for years. So it is no wonder that China wanted to close them down, to keep information under control. In the last few months more people in China are finding their VPN is not working.

Meanwhile in South Korea, new legislation means telecommunication companies are forced to put software inside teenagers’ mobile phones to monitor and restrict their access to the internet.

Both these examples suggest that technological advances are giving all the winning censorship cards to the overlords.

But it is not as clear cut as that. People continually find new ways of tunnelling through firewalls, and getting messages out and in. As new apps are designed, other opportunities arise. For example, Telegram is an app, that allows the user to put a timer on each message, after which it detonates and disappears. New auto-encrypted email services, such as Mailpile, look set to take off. Now geeks among you may argue that they’ll be a record somewhere, but each advance is a way of making it more difficult to be intercepted. With more than six billion people now using mobile phones around the world, it should be easier than ever before to get the word out in some form, in some way.

When Writers and Scholars International, the parent group to Index, was formed in 1972, its founding committee wrote that it was paradoxical that “attempts to nullify the artist’s vision and to thwart the communication of ideas, appear to increase proportionally with the improvement in the media of communication”.

And so it continues.

When we cast our eyes back to the Soviet Union, when suppression of freedom was part of government normality, we see how it drove its vicious idealism through using subversion acts, sedition acts, and allegations of anti-patriotism, backed up with imprisonment, hard labour, internal deportation and enforced poverty. One of those thousands who suffered was the satirical writer Mikhail Zoshchenko, who was a Russian WWI hero who was later denounced in the Zhdanov decree of 1946. This condemned all artists whose work didn’t slavishly follow government lines. We publish a poetic tribute to Zoshchenko written by Lev Ozerov in this issue. The poem echoes some of the issues faced by writers in Russia today.

And so to Azerbaijan in 2015, a member of the Council of Europe (a body described by one of its founders as “the conscience of Europe”), where writers, artists, thinkers and campaigners are being imprisoned for having the temerity to advocate more freedom, or to articulate ideas that are different from those of their government. And where does Russia sit now? Journalists Helen Womack and Andrei Aliaksandrau write in this issue of new propaganda techniques and their fears that society no longer wants “true” journalism.

Plus ça change

When you compare one period with another, you find it is not as simple as it was bad then, or it is worse now. Methods are different, but the intention is the same. Both old censors and new censors operate in the hope that they can bring more silence. In Soviet times there was a bureau that gave newspapers a stamp of approval. Now in Russia journalists report that self-censorship is one of the greatest threats to the free flow of ideas and information. Others say the public’s appetite for investigative journalism that challenges the authorities has disappeared. Meanwhile Vladimir Putin’s government has introduced bills banning “propaganda” of homosexuality and promoting “extremism” or “harm to children”, which can be applied far and wide to censor articles or art that the government doesn’t like. So far, so familiar.

Censorship and threats to freedom of expression still come in many forms as they did in 1972. Murder and physical violence, as with the killings of bloggers in Bangladesh, tries to frighten other writers, scholars, artists and thinkers into silence, or exile. Imprisonment (for example, the six year and three month sentence of democracy campaigner Rasul Jafarov in Azerbaijan) attempts to enforces silence too. Instilling fear by breaking into individuals’ computers and tracking their movement (as one African writer reports to Index) leaves a frightening signal that the government knows what you do and who you speak with.

Also in this issue, veteran journalist Andrew Graham-Yool looks back at Argentina’s dictatorship of four decades ago, he argues that vicious attacks on journalists’ reputations are becoming more widespread and he identifies numerous threats on the horizon, from corporate control of journalistic stories to the power of the president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, to identify journalists as enemies of the state.

Old censors and new censors have more in common than might divide them. Their intentions are the same, they just choose different weapons. Comparisons should make it clear, it remains ever vital to be vigilant for attacks on free expression, because they come from all angles.

Despite this, there is hope. In this issue of the magazine Jamie Bartlett writes of his optimism that when governments push their powers too far, the public pushes back hard, and gains ground once more. Another of our writers Jason DaPonte identifies innovators whose aim is to improve freedom of expression, bringing open-access software and encryption tools to the global public.

Don’t miss our excellent new creative writing, published for the first time in English, including Russian poetry, an extract of a Brazilian play, and a short story from Turkey.

As always the magazine brings you brilliant new writers and writing from around the world. Read on.

© Rachael Jolley

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.

The Sport for Rights coalition strongly condemns the sentencing of Azerbaijani journalist Khadija Ismayilova to a staggering 7.5 years in jail. On 1 September, the Baku Court of Grave Crimes convicted Ismayilova on charges of embezzlement, illegal entrepreneurship, tax evasion, and abuse of office. Ismayilova was acquitted of the charge of inciting someone to attempt suicide. Sport for Rights considers the charges against Ismayilova to be politically motivated and connected to her work as an investigative journalist, particularly her exposure of corruption among the ruling Azerbaijani elite.

“We condemn today’s verdict in the case of Khadija Ismayilova, which puts an outrageous yet expected ending to the grotesque proceedings against her”, CPJ Europe and Central Asia Program Coordinator Nina Ognianova said. “The time for business as usual with Azerbaijan is over. We call on Baku’s counterparts in the international community to make no further dealings with this highly repressive state until Ismayilova is unconditionally released and fully acquitted of all fabricated accusations”.

“Khadija Ismayilova’s trial failed to meet minimum fair trial guarantees, a pattern that has been regularly observed by IPHR’s monitors in similar cases in Azerbaijan”, said Brigitte Dufour, IPHR Director. “The defence’s motions are routinely rejected, which runs contrary to the principle of equality of arms – a cornerstone of the right to a fair trial – and indicates that the judges in these trials are openly siding with the prosecution”.

One of Azerbaijan’s most prominent investigative journalists, Ismayilova is also among the most courageous, one of very few willing to report on risky topics such as human rights violations and corruption. In the months leading to her arrest in December 2014, Ismayilova was aware she could be targeted, which she linked to her investigations into the business interests of President Ilham Aliyev’s family. Despite being warned not to return to the country from trips abroad – during which she spoke at international organisations on abuses taking place in Azerbaijan – Ismayilova persisted, speaking out critically until her arrest, and even afterwards, in letters smuggled out from jail.

Sport for Rights believes that in jailing Ismayilova, the Azerbaijani authorities sought to silence her critical voice before the country faced increased international media attention during the inaugural European Games, which took place in Baku in June 2015. Sport for Rights has referred to Ismayilova as a “Prisoner of the European Games” – along with human rights defenders Leyla and Arif Yunus, Rasul Jafarov, and Intigam Aliyev, who were also arrested in the run-up to the games.

“For her thorough and fearless investigative journalism, which has uncovered corruption at the highest levels of power, Khadija has earned numerous accolades, including PEN American’s 2015 Barbara Goldsmith/Freedom to Write Award”, said Karin Deutsch Karlekar, director of Free Expression programmes at PEN American Center. “However, speaking the truth has grave consequences in Azerbaijan, where independent reporting has been all but extinguished through farcical trials, imprisonment, murder, and other forms of severe harassment. We demand that the government cease this unprecedented witch-hunt against journalists and their family members, and enable Azerbaijani citizens to freely access a range of news and information”.

The harsh sentencing of Ismayilova is the latest incident in an unprecedented crackdown being carried out by the Azerbaijani authorities to silence all forms of criticism and dissent. Less than two weeks before Ismayilova’s verdict, the same court sentenced human rights defenders Leyla and Arif Yunus to 8.5 and seven years in jail, respectively. Authorities have so far disregarded the widespread calls for humanitarian release of the couple, who both suffer serious health problems that continue to worsen in custody. Human rights defenders Intigam Aliyev, Rasul Jafarov, and Anar Mammadli are also serving staggering sentences of 7.5 years, six years and three months (recently reduced from 6.5 years by the appellate court), and 5.5 years, respectively, all on politically motivated charges.

The situation for journalists is also dire. On 9 August, journalist and chairman of the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety Rasim Aliyev died in hospital after being severely beaten the previous day. Aliyev had reported receiving threats in the weeks leading to the attack, and the police failed to provide him with protection. This attack followed an earlier high-level threat against an Azerbaijani journalist, Berlin-based Meydan TV Director Emin Milli, in connection with his critical reporting on the European Games. In addition to Ismayilova, journalists Nijat Aliyev, Araz Guliyev, Parviz Hashimli, Seymur Hezi, Hilal Mammadov, Rauf Mirkadirov, and Tofig Yagublu are also behind bars on politically motivated charges.

The Sport for Rights coalition reiterates its call for Ismayilova’s immediate and unconditional release, as well as the release of the other jailed journalists and human rights defenders in Azerbaijan. The coalition also calls for the Azerbaijani government to take immediate and concrete steps to improve the broader human rights situation in the country, particularly in the context of the upcoming November parliamentary elections. Without independent media coverage, including critical voices such as Ismayilova’s, the elections cannot be considered free and fair. Finally, Sport for Rights calls for greater vigilance by the international community to developments in the country, and increased efforts to hold the Azerbaijani government accountable to its international human rights obligations.

Supporting organisations:

ARTICLE 19

Civil Rights Defenders

Committee to Protect Journalists

Freedom Now

Front Line Defenders

Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights

Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF)

Index on Censorship

International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), within the framework of the Observatory for

the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

International Media Support (IMS)

International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR)

NESEHNUTI

Norwegian Helsinki Committee

PEN American Center

People in Need

Platform

Polish Green Network

Solidarity with Belarus Information Office

World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT), within the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders